Ruby, the Farm Truck, Pt. 1

He Bought It As a Parts Vehicle, But Then Had Second Thoughts. What Happened With the ’67 Pickup? Let’s See…

Editor’s note: This month we’ll begin an occasional series detailing the story of an old farm truck and its future use.

WHERE IS IT written that a parts car must sit under a tarp, waiting for the day its owner decides to take it to pieces?

I had a different idea in mind for the red 1967 Ford F-250 I found on a farm just a mile north of my place.

True, its running gear is identical to that of Old Blue, my daily driver of the same year, whose revival was detailed in four Auto Restorer issues, November 2008 through February 2009. Both trucks have 240-cubic-inch 6-cylinder engines; Warner 4-speed, floor-shift transmissions; and Dana 60 rear axles.

In other words, the red pickup would make a perfect donor vehicle for Old Blue—eventually. In the meantime, I hoped to get some use out of it by putting it back on the road.

In Outdoor Storage

It evolved that Steve, the farmer on whose land the truck resided, was as eager to get rid of the old eyesore as I was to acquire it. The truck, I learned, belonged not to Steve but to a neighbor on a nearby acreage. The neighbor, Dave, had moved away with the promise to return for his truck within a year if Steve would store it for him. Meantime, the truck had sat in a pasture, braving the weather of four seasons (Photo 1). If its paint sparkled, it was only because frost covered the old truck on a cold, clear January morning when I rescued it from the rubbish pile where it had sat for a year.

Because the year was up, Dave was a motivated seller. I knew he wanted to avoid hauling the truck to his new home in town, where, presumably, he didn’t have room for it.

My $400 Gamble

Dave was asking $500, given that his son was starting college and needed the money. (Ah, the old myson’s-off-to-college-and-I-need-the money gambit!) I counter-offered $300, citing the high cost of a much needed brake job and the unknown condition of the truck’s engine, which hadn’t run in over a year.

We compromised on $400 with an escape clause.

Dave and I struck our deal during an evening phone conversation in the dead of winter. In fact, the low temperature that night was forecast to be 9 degrees F. In the several years that he’d owned the truck, Dave conceded, he had topped off the antifreeze but had never changed or even tested it. Could the old coolant withstand below-freezing temperatures? He confessed that he didn’t know.

Thus our deal was contingent upon my close inspection of the engine. The following day, I discovered that the old antifreeze not only tested to minus 35 degrees F—Dave must have been topping off with straight antifreeze—but that the block, though covered with ice crystals, was free of cracks.

Accordingly, my money and Dave’s title changed hands.

Dave’s sister and brother-in-law, who bought the truck in 2000, had used it sparingly. Likewise,since acquiring the Ford, Dave had used the neglected old truck only intermittently, primarily as a trash hauler.

As such, it sat outside for months at a time while Dave gradually filled its box with tree limbs, old tires, rocks and other debris. When it was full, he’d drop a battery in it, pump up the brakes, prime the carburetor and roar off to the dump. Never mind that the truck’s plates had expired in 2001.

The layers of road dust on the dashboard, the dented tailgate, the greasy engine and the wired-up muffler spoke eloquently of the truck’s rough usage as an unappreciated acreage workhorse. Photo 2 is another view of the truck on the day the aged vehicle’s mini-restoration began.

Job 1: Parts and More Parts

Given its sorry condition, my first job was to thoroughly inspect the truck. I jotted a list of repairs I’d have to make and parts I’d have to locate to get it running well and looking presentable once again.

Afterward, I spent nearly two hours exploring my several cardboard boxes of 1967 Ford truck parts, pulling out a number of both new and used items from an inventory I had begun accumulating when I bought Old Blue in 1981.

For instance, I grabbed a nice used left-side taillight lens to replace the cracked one on the project truck.

Because “Ruby” (as my wife Carolyn optimistically dubbed the faded red F250 pickup) was missing her chrome horn button, I pulled one off a 1968 Ford F-100 parts truck I own. Although weather blistered, it would still honk a truck’s horn.

I grabbed a new oil filter from my inventory, as well, and so many other items that I began to question the wisdom of my $400 purchase. Rather than donating parts to my daily driver, my latest “parts truck” seemed to be actually depleting my existing inventory of parts. No matter, I told myself: Ruby’s mechanical parts will stay fresher, longer if I drive her rather than park her.

To round out my list of anticipated repairs, I dropped in a fresh battery and began testing the electrical system. I was prepared to find electrical problems galore in an ill-used old farmtruck.

But not only did the turn signals work—amazingly—so did the dome light, emergency flashers and the factory AM radio. And I had only to replace a missing fuse for the heater’s blower motor to spring to life.

Scars, Scrawls and Holes

That brings up the question: just how ill-used was Ruby? I distrusted her odometer reading, 44,000, which represented approximately 1000 miles per year since 1967. Such a low reading contrasted sharply with her many battle scars. No receipts or service stickers existed to confirm my suspicion that the true mileage was 144,000 or even 244,000.

My only evidence came later, when I flipped down the driver’s-side sun visor to discover a handwritten service log on its upper side: “51,xxx” (the last three digits were too faded to decipher), “64,183” and “69,xxx.” Under the hood, I found similar jottings, which are common to farm vehicles.

Rather than keep a printed service log, I’ve discovered,some farmers willscrawl pencil notes directly onto their tractors, trucks and cars.

I imagine someone used the visor to record oil changes, leaving me greatly concerned by the 13,000-mile gap between the first two odometer readings. Regardless, now that I knew the truck’s actual mileage was at least 144,000 miles, I adjusted my expectations accordingly.

Are holes in the body of a farm truck an indicator of age—similar to the growth rings of a tree—or are they an indicator of abuse?

I counted 17 drilled holes apiece on the right and left top rails and sides of the box. The truck bed contained too many drilled holes to count. I have six holes drilled in the left door plus two in the left side of the cowl, the latter undoubtedly for a long-gone dealership tag.

The six holes drilled in the right door were apparently for a right-side mirror, now just a memory. Some of the holes I would plug to keep water out. The others? I planned to leave them as conversation pieces.

Two Simple Restoration Goals

I decided upon a pair of pointedly simple goals for fixing up this truck: 1. do it as quickly as possible and 2. do it as cheaply as possible. I wanted the truck to perform reliably, of course, but I had no thoughts of building a prize-winning show truck. Quite to the contrary, I merely wanted to squeeze a few more miles out of an old truck that (so to speak) already had at least one wheel in the boneyard.

Therefore, I was happy, even eager, to replace her worn-out parts with some nice used parts. I did so with a number of tune-up items that I’d retired from Old Blue—spark plugs, a distributor cap, contact points and condenser, and ignition wires—saving perhaps $50 right there. I opted against using “pre-owned” radiator hoses only because the old ones were in truly poor condition.

For the first time ever, I considered buying used tires to save hundreds of dollars over new. At first, I thought I’d restrict Ruby to the barbed-wire confines of my acreage, thereby saving the cost of licensing and insuring her. Heck, for driving in the fields exclusively I could even forego the $24 charge for balancing the used set of tires.

A Major Change In Plans

But once I awoke to Ruby’s greater usefulness as both a farm and freeway truck, I invested more time and money than I otherwise would have, just to make her safe and reliable for highway driving. Therefore—as with every other restoration, large or small, that I’ve ever undertaken—it ultimately grew into a bigger project than I’d intended.

In my original wild-eyed plan, I’d even believed that by bearing down hard enough on the project and collecting all the essential parts beforehand, I’d be able to complete the necessary repairs in just two days. No—really!

However, in line with my new approach to the project, I scoured the local parts stores and tapped some online suppliers—primarily RockAuto.com—to buy radiator hoses, a fuel filter, muffler,battery cables and a host of other new parts. As for supplies, I stocked up on motor oil, gear oil, antifreeze and the like. My idea, largely successful, was to avoid time-robbing trips to the parts stores while in the midst of repairs.

Another challenge concerned the bitterly cold weather.

Temporarily lacking heated shop space on my acreage, I was forced to restore Ruby in a rented shop in town some 20 miles away. That meant I had to either transport a variety of specialty tools—from jack stands to engine-test equipment—or risk needless delays.

Imposing an Orderly Approach

I arranged all these parts, supplies and tools on a makeshift workbench in my rented shop, using alphabetical parts groupings: axles, brakes, clutch, cooling, electrical, and so forth.

For instance, in the “cooling” group I’d laid out such parts as a new thermostat and gasket, a fan belt, and radiator and heater hoses; such supplies as antifreeze, distilled water and a plastic jug for mixing the coolant in a 1:1 ratio; and such tools as a special socket for opening the radiator petcock, a block and radiator flushing gun and an antifreeze tester (Photo 3).

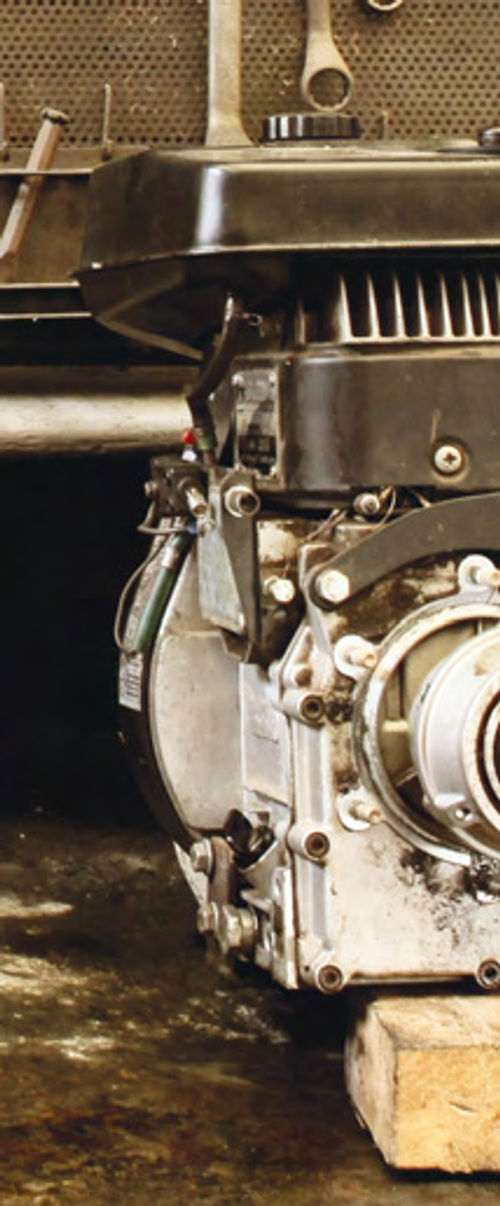

En route to the shop with Ruby on a car-hauling trailer I made one important stop…at a self-serve car wash that uses very hot water. There, I spent $14 during a 30-minute session, blasting off as much old grease asI could from Ruby’s engine, frame, transmission, differential and universal joints. A coin-op car wash transformed the lump of grease under Ruby’s hood into a nicely painted engine (Photos 4 and 5). Being able to see what I was doing would make repairing her that much easier.

“In my original wild-eyed plan, I’d even believed that by bearing down hard enough on the project and collecting all of the essential parts beforehand, I’d be able to complete the necessary repairs in just two days. No—really!”

Once I’d unloaded Ruby into my heated shop, I started in with some basic maintenance: oil and grease. The old oil that gushed from the drain-plug hole was, predictably, dark. I noted with pleasure, however, that it was free of rust flakes, metal particles and water.

Rust stains marked the underside of the truck’s white Wix oil filter, which, when I removed it, shed nary a drop of oil. In the year or more that the truck had been sitting in the outdoors, all of the oil in the filter had apparently drained back into the engine.

After spinning on a new oil filter and adding fresh oil to the crankcase, I removed the engine’s old oil-bath air cleaner. I dumped out the old oil and then, with a putty knife, scraped the pasty goop from the bottom of the filter canister. Next I submerged the air cleaner’s three pieces—the lid; the bottom bowl, which traps dirt in a puddle of 50-weight oil; and the wire-mesh insert that sits inside the bowl—in my solvent tank to soak.

Gear Lube & Lug Nuts

Crawling beneath the truck with an open-end wrench, I popped out a square drain plug to let the transmission spill its old oil. To thoroughly clean the threads and body of the drain plug, I spent some time at a floor-mounted electric motor equipped with wire buffing wheels. Finally, to prevent galling them, I lubed the threads with anti-seize compound and reinstalled the drain plug.

When you’re faced with cramped working quarters, it’s often necessary to fill a manual transmission with a suction gun and tube. Fortunately, I had enough room beside Ruby’s transmission to fill it by emptying quart gear-lube bottles directly into the filler-plug opening on the side of the case.

I did need a suction gun at the rear of the truck because the differential— as a safety measure, I presume—lacks a drain plug. By inserting my finger inside the filler-plug hole, I discovered that the differential oil level was down about two inches. I withdrew the old oil from the differential by inserting a suction-gun tube into the filler opening. As with the transmission, I easily refilled the differential by tipping quart bottles of gear oil directly into the filler hole.

Because the wheels had a date at the tire store it was time to loosen all 32 lug nuts, so I raised the truck with a floor jack and placed it on four jack stands, one at each corner of the vehicle. Before removing the front wheels, I placed my hands on each tire in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions and attempted to rock it back and forth—a test for king pin wear. Ruby passed muster.

But then, even with my air compressor’s 175 pounds per square inch, my air impact wrench couldn’t loosen most of the lug nuts. Were the threads rusty? Not at all. Some clown posing as a mechanic had simply torqued the nuts to perhaps three times the 75 ft.-lbs. at which I normally torque them.

The front-wheel lug nuts were particularly tight, forcing me to throw all my weight onto a 17-inch-long breaker bar. At one lug nut, I had to actually jump on the breaker bar. It’s no wonder that loosening 32 lug nuts took me 40 minutes, which included some time jockeying the floor jack.

In the next installment, we’ll restore a neglected fuel system.

Meanwhile, if you’ve had experience with a farm truck yourself, why not share what you learned with us. And if you have an image of your vehicle, we’d like to see it.