When the Automakers Turned to Muscle

It Was a Time When a Youth-Driven Market Demanded Performance, and the Car Companies Responded With a Growing Variety of Tire-Burning Offerings.

Editor’s note: The following has been excerpted from “Ford Total Performance,” the story of “Ford’s Legendary High-Performance Street and Race Cars.” This segment centers on 1968, a year when 427- and 428-cid V-8s were readily found at drag strips, race tracks…and at local Ford dealerships.

Bunkie and the Jets!

In February 1968, GM’s Bunkie Knudsen was named president of Ford. A month earlier, 1968 1/2 Cobra Jet Mustangs swept Super/Stock Class and Eliminator titles at the NHRA Winternationals. Total Performance was still alive and well in Dearborn.

Henry Ford II shocked the industry and ruffled quite a few feathers internally when he poached Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen from General Motors before the ink was dry on his resignation papers in February 1968. Knudsen was named president of Ford Motor Company. Some of those feathers belonged to Ford executive vice president Lee Iacocca, who had been on the fast track for the job. Getting Bunkie to cross over to Ford was considered a major coup. His was one of the most prestigious names in the industry and had been a candidate for the presidency of GM. Unlike most “suits” at his level, Knudsen was a serious car guy and racing enthusiast. When Ed Cole got the nod to run GM in 1967, Knudsen remained executive vice president and head of GM Overseas.

Knudsen was the son of William Knudsen, a former Ford executive and president of GM from 1937 to 1940. After twenty-nine years at GM, Knudsen was not happy being passed over. He entered into negotiations with Henry Ford II in January 1968 and, on February 6, was named president of Ford Motor Company. Knudsen had been a hands-on product guy at GM when he headed Pontiac and Chevrolet divisions, and wasted no time in making changes to products already approved and interfering in areas that fell under Iacocca’s control. Almost immediately, Iacocca and Knudsen started getting in each other’s faces.

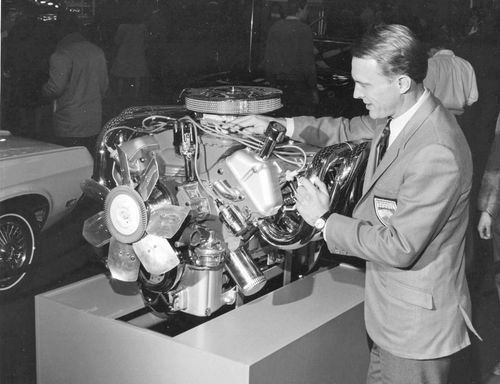

Rarely does the president of a carmaker get directly involved in performance product and racing decisions. A chief executive who attends NASCAR races and hangs out with car builders and racers at tracks is even more rare. Knudsen did. He brought Larry Shinoda with him, a stylist at GM who had been involved in the design and development of the Corvette Sting Ray. It took little time for Knudsen to bring in his pal, Mickey Thompson, to talk about land speed and endurance racing at Bonneville. Thompson had worked with Knudsen on Pontiac racing projects. Knudsen’s mantra once arriving at Ford was, “Build what we race and race what we build.” He would become a champion of the Boss 429 engine program.

The big product news for 1968 was the announcement of the availability of 427/390 and 428/335 Cobra Jet engines in Mustangs, Fairlanes, Cougars, and Cyclones. First came the 427 option, available only with automatic transmission and in early-build cars. The 427 was being phased out of production at the end of 1967. While 427 Mustangs were advertised, they could not be ordered at dealerships. A total of 357 GT-E 7-Litre Cougars were built with 427/390 engines with C-6 automatics.

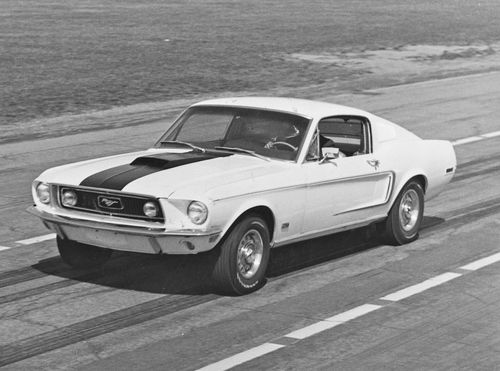

Ford’s primary performance car for 1968 was the midyear 428 Cobra Jet Mustang, with four-speed manual or beefed C-6 automatic transmissions. In 1968, the Mustang was pretty much a carryover 1967 vehicle with small trim, suspension, and safety updates, plus important powertrain changes. Ride and handling was improved and, if you ordered a V-8, you could opt for Michelin radial tires for the first time. Gone was the four-barrel 289 small-block, including the venerable 271-horsepower, solid-lifter version, replaced by a new 302 smallblock. You could order a 390/325 bigblock or wait for the midyear introduction of the potent 428 CJ engine.

Cars tagged for the new CJ option automatically received special attention at the San Jose and Metuchen assembly plants. Those cars were given reinforced front shock towers and 9-inch rears with thirty-one-spline axles, plus four-speed Mustangs were equipped with staggermount rear shocks. All CJ Mustangs were factory fitted with a functional fiberglass hood scoop with ram-air induction capability. Under full throttle acceleration, a vacuum-controlled flapper on the air cleaner assembly opened up, allowing air to go directly to the carburetor, bypassing the air filter. Under normal driving, air was channeled through the air filter.

Before there was a production 428 Cobra Jet, the CJ Mustang was first conceptualized by Bob Tasca, working with John Healey and Bill Lawton, and presented to Ford. Tasca had built his own “Cobra Jet”—a KR-8 “King of the Road” Mustang powered by a 428 engine with 390 GT cam and valvetrain, heads from a low-riser 427, 428 Police Interceptor intake manifold with a 735-cfm Holley, and 390 GT exhaust manifolds. He felt that Ford didn’t have a suitable Mustang to compete with Chevrolet’s new Camaro, available with a 396/375 solid-lifter bigblock. Tasca had built a Mustang that would give any stock Camaro nightmares! Tasca’s KR-8 concept was well-received and became the inspiration for the production 428 CJ Mustang.

Prior to regular production, Ford built fifty-four Wimbledon White Mustangs with 428 Cobra Jet engines, specified by DSO892017, at the Dearborn plant. They were ordered specifically for NHRA Stock and Super/Stock competition. Essentially, they were base SportsRoof Mustangs, not GTs, built without radios and heaters, and with trunk-mount batteries, Police Interceptor drivetrains, and 3.89 limited-slip rears with traction bars. Twenty of them were produced without seam sealers or sound deadening materials. Two different engine packages were employed—one rated at 335 horsepower for C/Stock, the other with horsepower north of 360 for Super Stock/E. Distribution of the first Cobra Jet Mustangs included Ford dealers involved in drag racing programs in the U.S. and Canada, with Tasca Ford receiving the most—ten CJs. Approximately ten were also assigned to Dick Brannan’s group at Special Vehicles Activity.

Dynamometer testing at Ford revealed that a 335-horsepower CJ engine with headers, open exhausts, maximum tuning specs, and without air cleaner or alternator produced 411 horsepower. A red 1968 Mustang CJ evaluated at the Kingman, Arizona, proving ground clocked a best time of 108-plus miles per hour in 13.4 seconds.

A small fleet of Cobra Jet Mustangs was reserved for the model’s California introduction at the AHRA Winternationals at Lions Drag Strip on January 28 and the NHRA Winternationals at Pomona on February 2 through 4, 1968. Those cars were shipped to Holman-Moody-Stroppe in Long Beach for race prepping. Engines used in the C/Stock Mustangs had “stock” specs with forged 11:1 pistons; 427 steel rods; and .509-inch-lift, 282-degreeduration hydraulic-lifter cams and valve trains; and headers. These cars had 4.44 rears with Detroit Lockers, traction bars, and Goodyear slicks. The modified engines permitted in Super/Stock were built with 11.6:1 pistons; GT40 forged steel rods; deep oil sumps with windage trays; steel cranks; .600-inch-lift, 380-degreeduration solid-lifter cams and Crane valve trains; lightweight valves; and dual-inlet, 735-cfm Holleys on 427 aluminum intake manifolds. Rear end gearing on the S/S cars was 4.71 with a Detroit Locker and bigger Goodyear slicks.

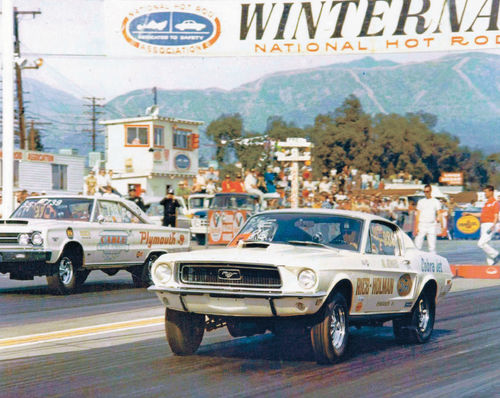

The Cobra Jet had a less-than-successful launch at the AHRA Winternationals when Hubert Platt red-lighted in his C/ Stock Mustang, clocking a 12.62 in the first round of Top Stock. It was another story at the NHRA Winternationals when five Ford Drag Team drivers—Jerry Harvey, Al Joniec, Don Nicholson, Hubert Platt, and Gas Ronda—showed up with six cars for C/SA, SS/E, and SS/EA. Dearborn was there in force to showcase the hottest new “production” pony car. It would be the first NHRA National meet that Ford dominated.

It was Al Joniec, driving the RiceHolman SS/E Cobra Jet, VIN #5050, that established the new CJ Mustang as the car to beat. Four of the six CJs made it to their respective class finals and Al Joniec beat teammate Hubert “Georgia Shaker” Platt’s CJ to win SS/E. He ran 120.6 miles per hour in 11.49 seconds. Following that, he beat Dave Wren’s Plymouth for Super/ Stock Eliminator.

“My CJ Mustang was capable of running in the low 11s in the 122-mile-per hour range, though I didn’t have to run it that hard to win,” said Joniec during a recent interview. “Since it was the official introduction of the Cobra Jet, I didn’t want to lower the record and lose any advantage at future events.”

However, Joniec ran his Super/Stock CJ at just one more NHRA meet, at Englishtown Raceway Park in New Jersey. He recalled, “There was no way I could make any money running my Mustang in Super/Stock, so I replaced the 428 CJ with the latest 427 with Tunnel Port heads and intake. I ran it as a successful match racer, Hairy Too, and in the 3200-pound class on the NASCAR circuit.”

In the 1970s, Joniec’s Mustang was converted back to legal NHRA Cobra Jet specs and set a number of records by then-owner Dick Estevez. He set the NHRA SS/FA record at 10.83 seconds, plus records in IHRA competition. The iconic Joniec Cobra Jet has since been restored by Randy DeLisio and is in Nick Smith’s outstanding collection.

During the 1968 NHRA season, Cobra Jet Mustangs proved hard to beat. Don Nicholson, driving the Dick Brannan Ford Mustang, consistently ran in the low 11s at speeds up to 125 miles per hour. Barrie Poole in the Sandy Elliott Team CJ Mustang set the record in Canada at 11.87 seconds, later running in the 11.30s on tracks in the United States. Hubert Platt also set a number of records with his CJ during 1968.

Considering the Cobra Jet Mustang was a midyear 1968 1/2 model, Ford did quite well, selling a total of 1299 CJs, including thirty-four convertibles. Street performance was outstanding and the Mustang made a comeback after being caught short on displacement and power the year before. Ford underrated the production 428 CJ engines at 335 horsepower, primarily to try to gain an advantage in AHRA and NHRA classifications. It didn’t really work.

Streamlined fastback Ford Torinos and Mercury Cyclones, powered by the latest 427 Tunnel Port engines, dominated stock car racing in 1968. Torinos won twenty-one of forty-nine NASCAR Grand National races, with Cyclones picking up six GN wins. At the end of the season, Ford ran a full-page advertisement in enthusiast auto publications that said it all: “Grand Slam! Torino Wins 1968 NASCAR, USAC, and ARCA Championships.”

David Pearson nailed down his second NASCAR Championship, winning sixteen races in Holman & Moody Torinos. At the Daytona 500, Cale Yarborough drove the Wood Brothers No. 21 Cyclone to the win, averaging 143.25 miles per hour. LeeRoy Yarbrough, in a Junior Johnson Cyclone, and Bobby Allison, in Bondy Long’s Holman & Moody Torino, followed him. For the fifth year in a row, Dan Gurney won the Motor Trend 500 at Riverside Raceway. Gurney averaged 100.59 miles per hour on the 2.7-mile road-racing course to take the win, followed by David Pearson, Parnelli Jones, Bobby Allison, and Cale Yarborough in Ford Torinos.

Ford’s three-year winning streak at the Indy 500 was interrupted in 1968 by Bobby Unser, who achieved his first of three wins at the Brickyard in Rislone Racing’s Eagle-Offy. It was the last race for a front-engine car to be on the starting grid and the first race won by a turbocharged engine.

Finishing second was Dan Gurney, who drove his Olsonite Eagle-Ford powered by a naturally-aspirated, pushrod-design 305-cubic-inch Gurney-Weslake-Ford engine. The next best Ford finish was Denny Hulme, who took fourth place in another Olsonite Eagle-Ford. Gurney later won the USAC Champ Car Series Rex Mays 300 at Riverside in his Eagle-Ford. Hard-charging A. J. Foyt posted the first win for Ford’s new turbocharged engine at the USAC Hanford 250. It was clear that smaller displacement, high-revving, boosted engines were the future of Indy racing. Ford’s new turbocharged engine produced 750 horsepower at 9500 rpm—an incredible 4.46 horsepower per cubic inch!

After Ford pulled out of GT racing, John Wyer and Jim Willment campaigned JWA GT40-based Mirages. JWA converted the Grady Davis/Gulf Oil Mirages back to lightweight GT40 specs, complete with 289-cubic-inch Gurney-Weslake engines with Weber carburetors. Lucian Bianchi and Pedro Rodriguez drove P/1075, the former M-10003 Mirage, to win Le Mans in 1968. A Gulf Oil/JWA GT40 delivered Ford its third Le Mans win and the 1968 Championship.

Even with a new 302-cubic-inch smallblock motor with single and twin four-barrel carburetors, Ford and Shelby’s Trans-Am effort for 1968 could not stop the Penske/Donahue Z/28 Camaro juggernaut. Mark Donahue, in a Sunoco Blue Camaro, swept the series and gave Chevrolet the Trans-Am Championship in 1968. Jerry Titus and Ron Bucknum drove one of the two Shelby Mustang team cars and won the Daytona 24-Hour, but not much more.

Even with a new president who loved racing, Ford domination in stock car and drag competition, and some fresh products, Ford’s 1968 sales of 1.73 million vehicles were just a tiny tick higher than in the previous year. Sales had dropped in 1967 by almost 500,000 from 1966 numbers. Mustang sales in 1968 were 150,000 less than 1967.

Enthusiasts may have had much more to shop for, but insurance rates were putting a damper on the muscle-car marketplace. Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated and the war in Vietnam was escalating. Bunkie Knudsen had his work cut out for him.

1968 Shelby Cobra GT: Personal Luxury at Warp Speed!

Ford wanted more production; Shelby wanted more performance. The results: Cobra GT Mustangs—from 302 mild to 428 Cobra Jet wild.

I was elated when I returned from Shelby’s 1968 GT Mustang press program at Riverside Raceway in July 1967. The Shelby GT line was mildly restyled and packed full of upgraded comfort and convenience features, and power was right on the money. Plus, there was a regular production convertible for the first time. The snake charmer had done it again! I couldn’t wait to put together a cover story for the next issue of Hi-Performance CARS, November 1967. The cover line, under a shot of me driving next year’s Shelby GT Mustang on the track: 1968 Shelby 427 GT500, Hottest Mustang Yet!

Not long after the issue went on sale, we received mail objecting to our featuring a car that didn’t exist! There was a lot we came away with from that program that never happened—and even more that we didn’t know about that did happen. Between the long-lead press preview in July, the public announcement of the GT Mustang line in the fall, and a Ford press conference in the winter of 1967, there were more product and corporate changes at Shelby American than in 1965 to 1967 combined.

I mentioned the hot powerplant choices—427 in the GT500 and supercharged 302 in the GT350—that I found out later you couldn’t actually order. The 427 Shelby fastback I had driven at Riverside was a prototype built on a 1967 GT500. And, since I had recently watched GT Mustangs being built at Shelby’s LAX Airport facility, I had no reason to think that manufacturing would be relocated to Michigan, which it was. Or that Ford would be more involved in Shelby Mustang design and development to take the lead role in the manufacturing and marketing of the 1968 models.

Then there was the name change from Shelby GT to Shelby Cobra GT. Most of the media community was unaware that Carroll Shelby had sold his Cobra trademark rights to Ford in 1967. Ford wasted no time in utilizing its new purchase. (Years later, the Cobra trademark would be returned to Shelby after a legal battle.) The carryover 1967 roll bar in the coupe and padded roll bar in the convertible suddenly became an “Integral Overhead Safety Bar.” That was straight out of Ford Legal, crafted to ward off lawsuits in rollover accidents.

It was a brave new day for everything Shelby. Ford wanted to increase Shelby Mustang production beyond capability of the Shelby American’s current LAX facility. There was also talk about the airport not renewing Shelby’s lease as part of its expansion. In reality, Carroll Shelby never wanted to be a production car manufacturer. His passion was creating powerful two- and four-seat niche market performance cars with true sports car handling and braking qualities.

I attended Ford’s press conference in New York City on December 15, 1967, that focused on the transition of control of Shelby manufacturing and marketing operations. “Carroll Shelby and his Shelby Cobra GT cars will continue to be one of Ford’s better ideas,” said Ford Division Merchandising Manager William P. Benton. “Shelby American Inc. has been divided into three separate companies—Shelby Automotive, Shelby Parts, and Shelby Racing. Shelby Parts and Shelby Racing are headquartered in a 20,000-square-foot facility in Torrance, California. Ford Division will assist in the management of Michigan-based Shelby Automotive at Mr. Shelby’s request. Mr. Shelby will remain on the west coast to direct the parts and racing businesses. As in the past, Shelby Cobra cars will be sold through Shelby-franchised Ford dealers. The number of dealers will be increased from approximately 100 to 150 to provide representation in the top 111 market areas.”

Ford wanted to control production costs, something company “bean counters” had been trying to accomplish since the first Shelby Mustang in 1965. There were also quality control issues that Ford felt could be better dealt with if manufacturing was closer to Ford headquarters. Ford’s choice for Shelby Mustang final assembly was the Plastics Division of Tier 1 industry supplier A. O. Smith, a company founded in 1899 and located in Ionia, Michigan. They had been a supplier of lightweight steel chassis to both Ford and GM, and one of two mid-series Corvette Sting Ray body manufacturers. They had fiberglass production capabilities and a mini assembly line at their Ionia location.

The contract between Ford, Shelby, and A. O. Smith was signed in May of 1967, two months before we saw the 1968 models at Riverside. Titled “Basic Program Assumptions For 1968 GT350 and 500 Mustang,” original paperwork indicated that there would be three GT350s powered by 302-inch engines and three GT500s powered by 428 engines. The GT350s would be available with carbureted, fuel-injected, and supercharged engines. It was the same for 428 engines used in GT500s.

Communications between Shelby and the media never revealed that fuel injection was being evaluated, yet the program had been going on since mid-1967. Four 1968 Shelbys—two fastbacks, one notchback coupe, and one convertible—were used by Shelby chief engineer Fred Goodell to test a variety of mechanical and electronic fuel-injection systems supplied by Bosch/Bendix, Conolec, and Lucas.

Michigan-based Shelby Automotive, with Carroll Shelby on its board, managed the 1968 Cobra GT Mustang program. All donor Mustangs were built as KD (knockdown) units at Ford’s Metuchen plant and shipped by rail to Ionia. Mechanical changes were executed at the plant prior to shipping. A. O. Smith was responsible for the production of fiberglass conversion components—four-piece front end, louvered hood, scoops, rear spoiler and end caps, and taillight panel—using metal-matched dies for high quality. The new design hood utilized a stock Mustang locking mechanism and stylized twist-lock turn-knobs with Dzus fasteners.

Initially, Shelby Cobra GT Mustangs were offered with 302/250 four-barrel and 428/360 Police Interceptor four-barrel engines. Options included a 302/315 supercharged small-block and a 427/400 four-barrel engine. The two optional engines saw service only in prototypes. In May 1968, the 428 engine in GT500 models was replaced by the new, more powerful 428/335 Cobra Jet. The model changed to GT500KR. Some Shelby dealers advertised that the KR model produced 375 horsepower.

Since Ford had been planning the phase-out of the 427 street engine and developing the 428 Cobra Jet in 1967, there was never a business case for using the 427 in a Shelby Mustang. It offered more power and bragging rights than the more consumer-like 428, but the CJ variant with 427 heads and beefy lower end was not a consumer engine. The CJ offered 427 performance without the complications of adding an optional engine. The 427’s costs would never justify the gains.

There are enthusiasts who claim that Shelby built 427 GT500 Mustangs in 1968. The Shelby American Automobile Club is the official keeper of Shelby vehicle production and sales records. According to Rick Kopec, director emeritus of SAAC: “We have no factory information or sales invoices that detail 427 engines installed by the factory in 1968 Shelby Cobra GT Mustangs. This option was considered and planned, but was rejected by the time brochures and specification sheets had been completed and sent to dealers. When a new owner blew an engine and brought the car back to the dealer, it was not unheard of that the owner asked to replace the 428 with a 427. When these cars were purchased later, many thought the 427 engines were original. We know because we had to debunk all of those claims!”

Once Ford plants had tooled up for Cobra Jet Mustang production, the GT500KR replaced the GT500. Shoppers were confused, since the new 428 engine was rated at 335 horsepower and replaced a 360-horsepower engine. And they called it King of the Road!

After Cobra Jet Mustangs dominated Super/Stock competition at the NHRA Winternationals in February of 1968, enthusiasts were aware of Ford’s underrating of the engine. Documented test results showed that stock GT500s averaged 0-to-60 times in the high 6s and quarter-mile performance of approximately 100 miles per hour in the mid 14s. Similarly equipped KR models sprinted to 60 miles per hour in the mid 6s and covered the quarter mile in the high 13s at approximately 105 miles per hour.

Bob Tasca first used the tagline “King of the Road” for his KR-8 Cobra Jet concept Mustang, the inspiration for the production 1968 1/2 Cobra Jet.

Shelby had a lot of experience with Paxton superchargers, dating back to the first supercharged Shelby Mustangs in 1966. As in 1967, Shelby intended to offer supercharging on both small- and bigblock Mustangs in 1968. The prototype supercharged GT350 was equipped with the new 302-cubic-inch smallblock, boosted by a Paxton centrifugal supercharger force-feeding a sealed Autolite 650-cfm four-barrel. It had been dynamometer-tested at 315 horsepower at 5000 rpm and 333 pounds-feet of torque at 3800 rpm. It remained a prototype.

Supercharged 427 and 428 engines had been installed in the 1967 Shelby GT500 notchback, Little Red. Shelby engineers built at least two Paxton supercharged 1968 prototypes. One was the first GT500 convertible built, VIN #00056. It was an engineering prototype with a 428/360 engine used to evaluate different engines, induction systems, and drivetrains. It was later sold in original production condition without its supercharger and has since been restored to supercharged prototype specs.

As soon as Cobra Jet engines were available, Shelby Engineering special ordered (DSO-3037) a KR fastback in optional WT6066 special Yellow paint for supercharger fitment. The goal was to create an ultimate performance GT500KR with a potential horsepower rating in excess of 450. After the supercharger was added, GT500KR VIN #04102 was put on the road with Manufacturer’s plate 16-M826. Records indicate it was sold to Courtesy Motors in Littleton, Colorado, without the supercharger. It has been restored and the engine updated with a correct Paxton supercharger. The car is now in Kevin Suydam’s collection.

One of the modified 1968 Engineering vehicles survives with its engine intact. EXP-500, a green notchback coupe with black vinyl roof known as the Green Hornet was also used to test a number of powertrains. Originally a 390 Mustang, it was fitted with Shelby Cobra GT fiberglass body parts and a special fuel-injected 428 Cobra Jet backed by a C-6 automatic. It had been equipped with an independent rear suspension with coil-over shocks, reminiscent of IRS setups used on early Shelby Cobra race cars. The rear suspension was changed back to stock using a 9-inch rear with thirty-one-spline axles and locker. More importantly, it was one of Shelby’s mules for evaluating fuel-injection systems. In its final iteration, the CJ engine was fitted with a Conolec EFI (electronic fuel injection) system, still on the engine today. It has been restored and is in Craig Jackson’s collection.

The Green Hornet and Little Red served as prototypes for the 1968 GT/CS, or California Special and High Country Special notchback coupes. Essentially sales promotion models for specific regions, they were Mustangs customized with some Shelby Mustang body parts and trim. Built on both GT and base Mustangs, 3867 California Special models were built at the San Jose plant and distributed to dealers in a few areas. A total of 251 High Country Specials were sold only by Denver dealers. Unlike the Shelby Mustangs, the GT/CS and HCS side scoops were not functional.

For the 1968 model year, Shelby Automotive produced a record 4450 Shelby Cobra GT Mustangs, in excess of 1200 more than the previous year. Hertz purchased 225 GT350 fastbacks, two GT500 fastbacks, and one GT500KR convertible, all without special trim. Even with higher insurance rates, Shelby dealers sold 1053 KR fastbacks and 517 KR convertibles. For the first time, Shelbys could be ordered in standard or six optional colors. A total of 110 fastbacks and 49 convertibles came with special paint.

Even though Carroll Shelby was less involved with 1968 models than he had been in previous years, the Shelby mystique remained strong.