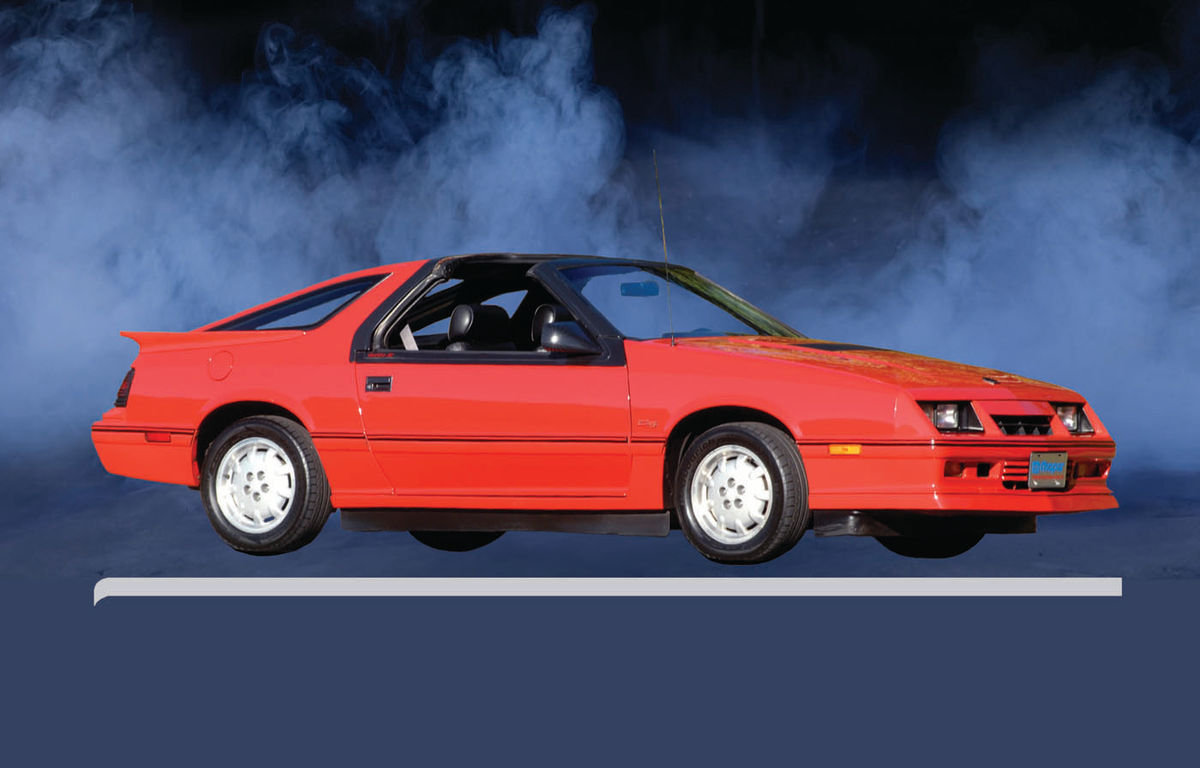

1986 Dodge Daytona Turbo Z C/S

Can You Call It a Muscle Car? Well, No. But It Could Be a Sign of Where the Hobby Is Headed.

MID-1980S PERFORMANCE CARS often seem marooned in the fog between the ’60s muscle and modern-muscle eras and while some examples probably deserve such a fate, others left an impression that goes to what many claim is the essence of the collector-car hobby.

“It’s something I always wanted,” said Gary Henry, whose 1986 Dodge Daytona Turbo Z C/S is shown here. “I think that’s what drives a lot of car enthusiasts to the types of cars they have. Maybe they had one when they were younger and got rid of it because of family and kids, drove it into the lake, blew it up racing or whatever. Or they just plain couldn’t afford it, which was my case. I could afford the payments on the car. I couldn’t afford the insurance.”

The insurance obstacle can be summed up by the Daytona’s 0-60 time of under 10 seconds, a figure unlikely to shock anybody today yet not one to be dismissed when the car was new. The result of what was calculated to be some pretty serious risk proved too much for many drivers.

“The insurance was astronomical,” Henry continued. “I remember one quote when I was looking at a Daytona Turbo Z right around ’85 or ’86. One quote back then was $2300 a year, and I had a perfect driving record.

“I don’t think I ever paid that much even when I had a Z-28.”

If that figure doesn’t look too bad, consider that it’s the equivalent of $4965 today. Astronomical? Maybe not, but certainly expensive enough to keep many young people out of the performance car of their dreams.

A Time of Automotive Transition

Muscle cars were little more than fond memories by 1976 thanks to the combined effects of increasing insurance premiums, rising fuel costs and intensifying regulations, so American automakers tried to put on a brave collective face. Loud stripes and graphics appeared, yet were obviously no replacement for the high performance that had been available just a few years earlier.

Lower compression and other design changes aimed at meeting the early emissions standards had siphoned horsepower, a development made more painful by the 1972 switch from gross to net figures used in describing a vehicle’s hp. Under the gross system, an engine running with no accessories, no air cleaner and no full exhaust system produces one number while under the net system, the same engine running with its accessories in place —as they’d theoretically be if the engine were in a car—produces a lower number.

Understandably, many of the era’s enthusiasts felt that they were seeing the end of the automobile as anything more than transportation.

The new cars that were being launched at the time didn’t help. At Dodge, the Aspen arrived to replace the Dart in 1976 and brought an R/T package with graphics, Rallye wheels and a 170-horsepower 360 V-8.

Furthermore, the compact Aspen had general problems. It rusted quickly and badly as it developed a reputation for questionable quality-control, but it was a reasonable compromise on size and when equipped with a six and four-speed overdrive transmission, returned tolerable fuel-consumption.

The Aspen and its Plymouth twin, the Volare, were filling a market slot with some success even as things were not going well at Chrysler. The corporation’s full-size models in the early 1970s had been big and seemed even bigger, two problems when it came to selling to a public coming face-to-face with increasing fuel costs. Given the tenor of the times, the company’s most important entry was an all-new one that arrived for 1978—the subcompact Dodge Omni and its Plymouth sibling, the Horizon.

Next to the compact Aspen sedan with its 112.7-inch wheelbase, the 99-inch Omni seemed small and that was far from the only difference setting it apart from other American cars.

For one thing, it used a transverse overhead-cam four to drive the front wheels—a first for a domestic mass-produced car—and for another, it was a four-door hatchback, all of which could be traced to the original Austin Mini and very much mimicked the contemporary Volkswagen Rabbit. (In fact, the Omni and Horizon were powered by a VW engine fitted with an enlarged Chrysler-designed cylinder head and intake manifold.)

The Omni and Horizon were initially derided by some, but their popularity, along with that of smaller cars in general, increased with the “oil shock” of 1979 and they continued in production through 1990.

The Times Called for More Changes

Those who had never driven anything like it surely were surprised at their first experience behind the Omni’s wheel. Admittedly, its 104.7-cubic-inch four produced only 75 horsepower, which was not a lot even in a 2100-pound car, but it could reach over 30 miles per gallon and combined with the standard four-speed to provide performance that was more than adequate. Handling was nothing like that of any other Dodge, although those who had driven comparable European cars undoubtedly found it familiar. In a way completely new to many American drivers, the Omni represented affordable fun.

The challenges facing manufacturers as they tried to meet the emissions regulations mentioned above as well as corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards, applied to small cars as well as mid-size and larger models, so there was no immediate boost in the Omni’s horsepower. Instead, a very different two-door joined the sedan for 1979 and was christened the O24—a sporty fastback with sharper edges and a slightly shorter wheelbase.

But even with new models in its lineup, Chrysler had been suffering for years from a combination of problems and by now was beginning to show it. Build quality and product decisions had deteriorated so badly by the time of the Omni’s introduction that the possibility of Chrysler’s death seemed increasingly real. Lee Iacocca, late of Ford, took over at Chrysler as it was in a tailspin and while even he probably wouldn’t claim total responsibility for the company’s rescue, the fact is that federal loan guarantees that came on his watch in 1980 were instrumental in Chrysler’s turnaround.

The Omni was instrumental, too, both in the sales it generated and the experience it provided. Its layout had helped to prove that good space-utilization and good fuel economy could coexist in a car that if not quite exciting, was at least pleasant.

The surprisingly winning role played by the Omni was soon repeated—with modifications—in the 1981 Dodge Aries and Plymouth Reliant compact K-cars. Looking more like conventional American cars with their three-box design, the two, while larger, were closely related to the Omni L-body under the skin with their front-wheel-drive and transverse overhead-cam four. Like the Omni, they endured abuse, although the sniping aimed at the K-cars was mostly because as two-doors, four-doors or wagons, they bordered on dull. What the critics didn’t know was that like the Omni, the K-car would go on to bigger things.

Another Mopar Fastback

For 1984, evidence of that corporate strategy came to life in the Dodge Daytona. The new model’s basis in the K-car was impossible to detect visually in that it looked nothing like the Aires or any of its relatives. Instead, it seemed to be a softer, rounder, bigger O24 with its fastback, thick B-pillar and long, sloping hood. Available as a base model as well as the Turbo and Turbo Z, the differences were ones that mattered. The entry-level 2.2-liter was fuel-injected and produced 99 horsepower while the Turbo jumped to 142. The Turbo’s equipment included a close-ratio five-speed and better suspension while moving up to the Z added ground effects, a spoiler and trim items, all of which came at a price; the base Daytona cost $8308 and the Turbo Z cost $11,494.

Dodge dropped the Turbo model in 1986, when the featured Turbo Z was built, but it also made improvements to the line beginning with the C/S package. Named for Carroll Shelby, it improved the Z’s handling with better sway bars and struts and added 6.5x15-inch wheels. That was in addition to standard Z features including body cladding, better seating and functional hood louvers. But the original owner of Henry’s feature Daytona went a few steps further.

“It’s basically got every option you could get except for cruise control,” Henry explained. “It’s got air, power windows, power door locks, leather interior, a T-top. It was the first year they made the Daytona with T-tops and it was the only year they had the C/S package on the top-of-the-line vehicle, the Turbo Z.”

He’d searched for about a year before finding it in an online auction in August of 2012 and since he’d also been considering a smaller Shelby Charger turbo, he’d already looked at about 10 examples of the two cars. There were lessons learned.

First, Some Frustration and Then…

“I had my mind set on one in New York,” Henry recalled, “but the guy lied to me. It was an ’85 Shelby Charger with the turbo engine and you know how they say pictures can make everything look beautiful? Well, they definitely made this car look beautiful and I told the guy it was 150 miles away. I said ‘tell me the truth. If this is a rustbucket, that’s not what I’m looking for,’ ‘Oh, no, no, no. It’s got a little bit of rust.’ Well, I got up there and I took one look at it and I said ‘you just wasted my…time.’ I was mad at the guy and I told him about it, too. I should’ve known, though, because the price was way too low.”

Of the Daytonas he’d found available, he drove only two and neither was a Turbo. Not driving the feature car before buying it was taking a chance, he admitted, and he didn’t even see it until he went to pick it up at a New Jersey dealer in September of 2012. His plan was to bring it home to Carbondale, Pennsylvania, on a friend’s rollback, so there was no reason to worry about getting it there. But what he learned from the seller—a long-time family-owned Chrysler dealership—strongly suggested that there would have been no reason to worry even without the truck.

“He had to lose money on this because he put a ton of money into this car as far as getting it back up to where it should be,” Henry said. “He replaced the (cracked) cylinder head assembly with brand-new stuff; he put all new brakes on it, ball joints, power steering rack, four new tires. The plastic bumpers get chalky, so he had them removed by his body shop, professionally redone and put back on the car. I basically didn’t have to do anything. He had done everything to the car.”

There was, however, what amounted to a fatal flaw in the dealer’s initial idea of keeping the Daytona for himself and it’s one that every hobbyist has faced at some point. The building housing the dealer’s collection lacked space, so the Daytona found itself on eBay. It was a pretty safe bet that the seller cared about the car and wasn’t simply dumping it, as Henry described the scene when he and his friend arrived to pick it up.

“He kept boasting about how clean this car was,” Henry said. “He puts it up on the lift and as it keeps going higher and higher, my buddy Frank and I are going ‘holy cow.’ We were mesmerized. My buddy was saying ‘there isn’t even any rust on the bolts.’”

Another bonus was that the dealer had the previous owner’s name and that enabled Henry to contact him. The Daytona had spent its life in a desert community in California before arriving in New Jersey, he learned, although that hadn’t kept it completely safe.

“They had an earthquake out there,” Henry explained, “and he had some implements hanging in the garage next to the car. A couple of them fell on the driver’s side fender and the hood. Hence, they had to be redone. Other than that, he guaranteed that the rest of the paint was original.”

Not All Daytonas Are That Good

Henry knows that someone looking for a comparable Daytona won’t have an easy time of it, especially if he’s doing his searching in the northern states with their snow and road salt. He’d been considering a restorable example, but was leaning toward a good original because he lacks the space to do major work on a car.

If he bought a project car now, though, his research before buying the feature car and his experience and knowledge of Daytonas when they were everyday drivers means he knows some of their significant potential problems.

“They were notorious for blowing head gaskets,” he said. “They were notorious for the turbos failing, although I know people who had 160,000 miles on them (so) I think it’s the way you maintain it.”

The manual transmission’s synchronizers can fail, something that makes third-to-second downshifts difficult in his car, and binding is a possibility on the power windows. Neither is a disaster, of course, and he said that when the time comes to replace the clutch, he’ll deal with the synchros. He hasn’t identified the windows’ problem yet, and until he does so, he’ll help them along manually.

But there are problems that make a powerful argument for walking away from a car.

“Floorpans,” Henry said. “Most of the cars from that era—Daytona, Charger any of them—the floorpans are ready to go. You can put your finger through them. That’s how the Charger up in (New York) was. I got under it, I looked at the floorpan and I said ‘I’m not even touching it.’ It was like a piece of parchment paper. That is one of the most common rust spots on them.

“I didn’t see one that had bad shock towers, but a lot of salt can collect up in there. That’s one reason I was so happy with where my car came from. It’s been well-preserved.”

If the car doesn’t show signs of terminal rust, he said, it needs to be checked carefully for completeness. He said missing or damaged body cladding is likely to be difficult—and expensive—to replace, as is some of the trim. He gave one example.

“This is another common problem with them,” he said, “and unless you know it, you won’t even notice it, but around the controls for the power door locks on the door, the rim is actually gone around them. It must break off. And on both sides.”

The completeness factor creates another concern and in Henry’s case, a twinge of regret.

“Do you know what one of my biggest fears is?” he asked. “Dropping one of those T-tops. I have this grip on them every time I take them off. And I could kick myself in the head because about a year, year-and-a-half after I bought the car, there was another one on eBay out in Wisconsin or Minnesota and it had been hit in the rear. The guy wanted $1500 for it and the T-tops alone were probably worth that. It was the same exact thing, T-tops and everything.

“I thought about it and I thought about it. I said ‘where am I going to put this thing? I have no place to store it.’ I should have. That was a stupid move.”

Not everything about the Daytona revolves around scarcity and difficulty, though, and Henry said that the day-to-day parts needed for maintenance and keeping the car on the road are easily found. That’s a good thing for him because he has “zero regrets” about having bought his Daytona. Why should he? Its torquesteer might surprise a driver who’d never experienced an older front-wheel-drive car and if he happened to be tall, he’d probably devote some time to finding a comfortable seat position, none of which matters very much to an owner who likes it.

“I get in that car,” Henry laughed, “I feel like I’m 20 again. It’s the truth. There’s not a day that I get in that car and take it to a show or just take it for a little ride on a nice, sunny summer day that I don’t get excited once I start it up and get going down the road.”

A Mustang Impersonator?

The Daytona typically is noticed both on the road and at shows and cruises, he said, something that doesn’t always translate to its being correctly identified.

“My favorite thing to do at a car show,” he said, “is to sit there behind the car. I don’t say a word. I just listen to the people as they come up and look at it. ‘Yeah, son, this is a Mustang’ and I’ll say ‘no, it isn’t.’ ‘Well, it looks like a Mustang.’ ‘No, it’s a Dodge Daytona Turbo Z.’ ‘Oh, I remember them.’ But I get a lot of people who think it’s a Mustang and that’s fine.”

His Daytona’s also been mistaken for a Laser, which is actually almost correct as the Laser is Chrysler’s version of the car, and when it’s been identified correctly at gas stops, long conversations have usually followed.

“Somebody next to me’ll be putting gas in,” Henry said, “and ‘man, that’s nice. Man, I remember these cars. These things were beautiful.’ Either that or somebody had another car like it. It literally will take me a half-hour to 45 minutes just to put gas in it…

“Another comment I get a lot is when they first look at it and I know there’s a bad ending to it. ‘Man, I used to have one of these back in college. I got drunk one night and wrapped it around a pole’ or ‘I rolled it into a field.’ It ends up with a disaster.”

Such stories undoubtedly help to account for the rarity of seeing the feature car’s siblings on the road, although they don’t have anything to do with the way some view a Daytona. In a world where vehicles built a century ago are driven and enjoyed, a 30-year-old car isn’t really old, but those that are saved at that age are the ones likely to be treasured as nice, mostly original examples in the future.

“I think my Daytona is a collector car down the road,” he said, “maybe in 15 or 20 years.”