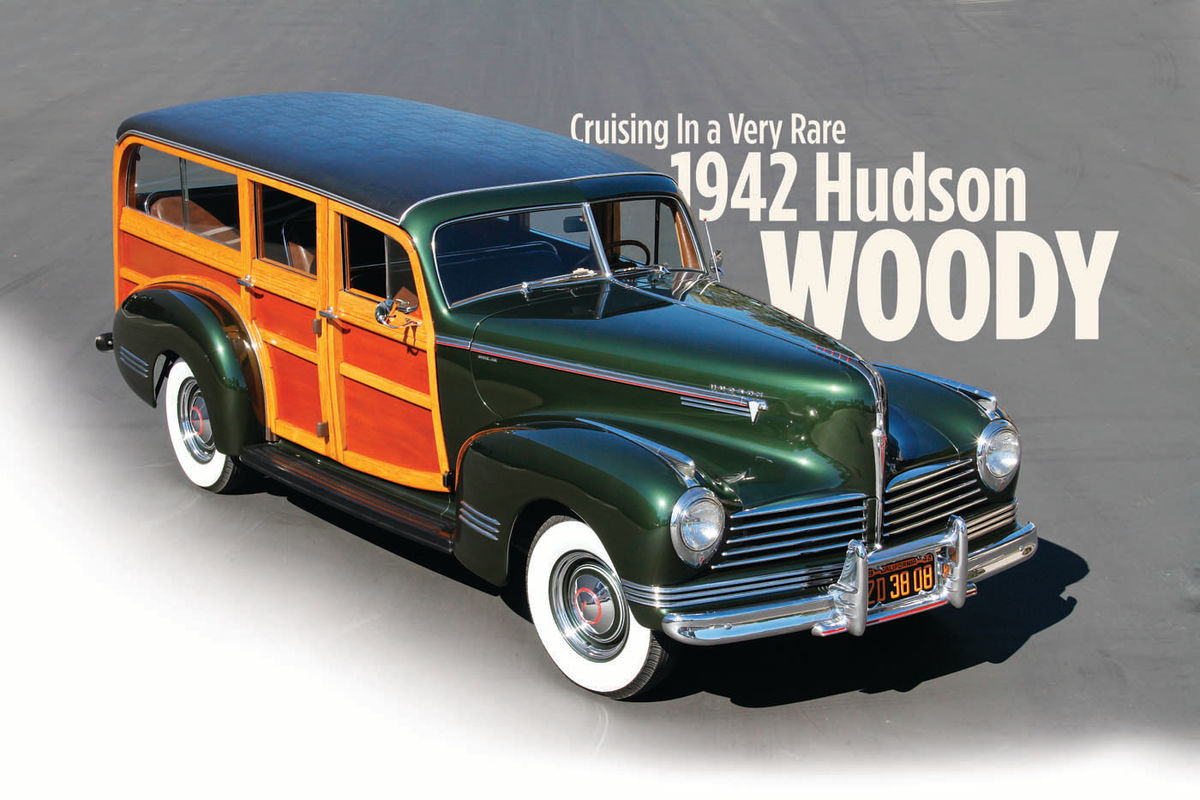

Cruising In a Very Rare 1942 Hudson WOODY

Join Us As We Go for a Drive In One of the Nicest Woody Wagons You’ll Find In Southern California. But Don’t Even Think of Tossing Your Dripping Surfboard and Wetsuit Inside This Special Car.

Editor’s note: While our emphasis at Auto Restorer generally is on cars and trucks that are readily available on the market and owned by folks who restore, maintain and drive their special rides, sometimes we can’t help but be attracted to a rare vehicle like this 74-year-old woody. So put some surfin’ music on your portable 8-track player and settle back in your favorite folding beach chair. We hope that you’ll enjoy visiting with this uncommon Hudson as much as we did.

Recently we found a 1942 Hudson Super Six woody wagon in the Crevier Classic Cars Collection in Costa Mesa, California. The Collection primarily is a dealership specializing in rare and exotic automobiles, but this Hudson isn’t available for sale. And when you find out just how rare the car is, you’ll understand why it isn’t sitting in a showroom wearing a price sticker.

Nevertheless, it was love at first sight for me. The Hudson was parked inside with other wagons of the period, but it truly was distinctive. It was lower and wider for one thing, and somehow seemed bigger. Its front end treatment was especially rounded and yet restrained.

Although I’ve been involved with vintage cars and trucks for decades, it was the first Hudson Woody I had ever seen. And most likely, it’s the only 1942 woody I ever will see…only 14 were built, and of those only three survive, two of which are awaiting restoration.

Getting Behind the Wheel

So you can understand why I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to take it out for a drive and have it photographed to give you an idea of what makes this car so special. In the process I discovered that driving a woody is not like driving other cars. It has a feel and ambiance all its own.

Once the big emerald green Hudson was moved from its berth, I climbed in and settled into its cocoa brown antique leather seat. From the outside the windshield looks low, but from inside the car you realize that the cowl is actually high, and looking out over it makes the hood appear enormous. I am over six feet tall and I don’t know how a shorter person could see out over it at all. The instrument panel is clean, simple, tastefully wood-grained and the epitome of ’40s streamlined styling.

None of the knobs on the dash stick out. Instead they are replaced with buttons that are flush with the panel. This was primarily for safety reasons, but it also makes for a very clean look. Even the radio is inset in a center grille so nothing sticks out.

There is no temperature gauge or oil pressure gauge either. Instead, Hudson pioneered warning lights, which, when you think about it, are more likely to get your attention anyway. In fact, many racecars have gauges and lights just to make sure the driver is fully aware of the car’s operating status.

A Big Car With a Small Engine

I turn the key and step down on the throttle pedal. This sets the automatic choke and engages the starter at the same time. The engine cranks over once and comes to life.

I let it run at fast idle for a minute in order to warm it up and to get the oil circulating, and then put in the silky smooth cork-lined wet clutch and pull the steering column-mounted gear lever into low. The linkage is tight and positive. The overdrive is already engaged. I know this because its knob is pushed in. We ease down the drive and turn into the street.

As we pick up speed I run out of gears pretty quickly. The engine is a modest 212-cubic-inch 102-horsepower flathead six, which was fairly typical of the era. It has only three main bearings and splash lubrication, but Hudson’s excellent chrome nickel engine blocks and careful, evolutionary engineering made for a durable, if rather tame, power plant. However, while the engine is of a rather diminutive size, the car’s ash and mahogany body weighs a lot. But the car’s chassis is fairly light. As El Hathaway, a Crevier representative who accompanied us explained, “It’s from a sedan rather than a truck, as was the case with some other wagons.”

That also helps explain the exceptionally smooth ride and easy center-point steering. There is no power assist, but once the car is rolling the steering is light, and the wheel is large to provide plenty of leverage.

The steering wheel also is unusually handsome, with the Hudson insignia emblazoned on a large shield in its decorative hub. A female designer named Elizabeth Ann Thatcher, who was specially recruited because the company wanted a woman’s input, designed the handsome dash and interior of the Hudsons of the period.

It Doesn’t Sound Like a Woody…

Surprisingly, there are none of the usual rattles and squeaks of a woody wagon. This is especially remarkable since this example’s timber is all original except for the mahogany insets. I look back in the rear view mirror through a vintage yacht-like tunnel of beautiful golden wood and see two big leather seats the size of those in busses. The vehicle smells of varnish and old leather, and has a sumptuous feel.

What made for a solid, rattle-free body, according to Hathaway, is the fact that the structural metal parts of the car are welded together as a unit and then attached to the frame, which is also a welded integral unit. This approach evolved later into the Step Down Hudsons built after the war, which were low, light and fast, thanks to the weight savings of the unit body and a later whopping 303-cubicinch inline six-cylinder engine.

There Was a Time When These Were Working Vehicles

As beautiful as it is, the Super Six wagon was not designed for selfindulgence. When our example was built, economy and dependability were what was important—not speed or style. In fact, when you raise the car’s forward-opening hood, you have to search for its engine, mounted so far back and down in the engine compartment that drivers sometimes stowed excess baggage in the large space between the radiator and the grille during winter weather to keep the radiator from freezing up from the wind-chill, according to Hathaway.

Our 1942 Super Six wagon actually evolved from what was in the old days referred as a “depot hack.” Such vehicles were originally horse drawn, but in the teens of the 20th century wooden bodies were constructed to fit automobile chassis (usually Model T Fords) so cabbies could pick up people at the train station along with their luggage. Only a brave few tried to drive automobiles across the country back when depot hacks were common.

And then in 1923 Star offered an entirely factory-built depot hack/ station wagon, but Star was a limited production independent that didn’t affect things much. (Star was a marque assembled by Durant Motors Co. which was established by William Durant, founder of General Motors, after he was forced out of GM.)

In 1929 Ford came out with the first factory-built woody wagon offered by the Big Three. Hotels, resorts and dude ranches purchased these vehicles to bring guests from railway stations to their establishments, hence the name station wagon. Sadly, today’s equivalent—the airport shuttle—is a big tin van with no style at all.

Trains were still the main means of long-distance travel even in 1942, and chances are our Hudson wagon was employed by a hotel, though by then station wagons were becoming popular for their versatility among suburbanites and ranchers as well. In a way, they became the first SUVs. But cost and the high maintenance required for wooden vehicles (manufacturers recommended varnishing them every six months) limited their sales somewhat, and caused them to be phased out by the early ’50s.

1942 Hudson Super Six Station Wagon Specifications

Engine: L-head inline six

Displacement: 212 cubic inches

Horsepower: 102 @ 4000 rpm

Fuel system: Carter Duplex 501S single barrel carburetor

Transmission: Three-speed manual column shift with overdrive

Clutch: Single-disc cork-lined wet clutch

Differential: Hypoid, ratio: 4.11:1

Tires: 15/7.10

Suspension

Front: Independent, coil springs, tubular hydraulic shock absorbers

Rear: Semi-elliptical leaf springs, tubular shocks

Dimensions

Wheelbase: 121 in.

Length: 207 in.

Width: 72.75 in.

Later, station wagons became popular with the parents of the baby boomers for obvious reasons, but they were fabricated out of steel by the early ’50s with only simulated wood decals to give them “the look.” And then a decade later the surfers of the ’60s bought the original woodies because by that time they were cheap, cool and they could accommodate surfboards. (Editor’s note: Think of The Beach Boys’ Surfin’ Safari… “We’re loadin’ up our woody with our boards inside…”)

Hudson Had Some Exotic Transmissions At the Time…

Due to its small engine and low gearing, our big Hudson wagon would not be freeway worthy if it weren’t for the company’s unique overdrive that engages in all three gears.

Actually Hudson had been creative with its transmissions starting in the mid- ’30s. First came the Electric Hand that used a little lever mounted on a stalk and solenoids to shift the transmission, though you still clutched manually. This Bendix system was used from 1935 until 1938, and was essentially the same as was used on the 1936 and ’37 frontdrive Cords.

After that a vacuum shift system called the DriveMaster became available that made it so you only had to shift the car into first gear using the clutch. After that the clutching and shifting was automatic. The system was similar to the Volkswagen Automatic Stick Shift. And in addition to this option Hudson had its own electric overdrive that, when combined with the Drive-Master vacuum shift became the Super-Matic. Our 1942 model came with only a standard manual shift transmission plus the overdrive that allowed a higher top speed; though 65 miles an hour would be wound tight for our wagon due to engine size and its low 4.11:1 rear end.

An Early Safety Braking System

Hudson’s transmissions were only some of the many unique features offered by the company in the early ’40s. For example, the brakes are hydraulic, but they also have a mechanical fail-safe mechanism that engages the emergency brake if the pedal drops below a certain point. That system came about because chief engineer Stuart Baits was badly injured when the brakes failed on a test car they were working on a few years earlier.

This braking arrangement is a great idea when you consider what happens when the standard single-bore master cylinder typical of the time fails. The brake pedal just goes to the floor, and you keep going unimpeded, until you collide with whatever is in front of you.

Another unique feature Hudson had was an independent front suspension with coil-over springs and aircraft shock absorbers. Many cars of the era still had solid front axles, and most cars of the time had complex shocks integrated into the upper A arms and were the knee-action type, which required more maintenance and were more complicated.

The rear suspension used aircraft shocks too, and had long leaf springs that made for a very smooth floating ride.

The Car Underwent a Complex Building Process

Hudsons also were bigger inside than most cars, and that gave the late ’30s and early ’40s Hudsons a rather inflated look, though not as inflated looking as the later step-down models. Hudson claimed 145 cubic feet of interior space in their sedans, and that compared very well with other large popular sedans, which only provided in the neighborhood of 121 cubic feet of interior space. As you might expect, our 1942 Super Six wagon was considerably bigger than the standard sedans.

The car has a big car feel and ride partially thanks to its weight with the massive ash framework of the body. When they were built, Hudson shipped the chassis and front end of the car to the cowl to Campbell Body Works in Waterloo, New York, to add the wood body. Understandably, this was a rather complex process that required a lot of time, and as a result, station wagons were expensive.

A Brief History of Hudson

The Hudson Motor Car Co. began life in 1909 when Roy D. Chapin, who had worked for Oldsmobile, teamed up with Old’s chief engineer Howard E. Coffin and eight Detroit businessmen to build a low-priced car. Joseph L. Hudson—who owned the biggest department store in Detroit, and possibly the world at the time— put up the lion’s share of the funds to get it going, so the company was named for him.

Hudson automobiles were an immediate success, and continued to do very well until the Depression in 1929 brought new car purchases to a virtual standstill. Hudson turned their less-expensive Essex line into the Essex Terraplane, which became just the Terraplane, which was intended to become a separate marque, though it ended its days in 1938. Hudson also made a smaller 202-cubic-inch six, and 254-cubic-inch flathead straight eight-cylinder engine for their Commodore series starting in 1941, but in 1952 the company returned to inline sixes exclusively until its merger with Nash in 1954 to form American Motors.

American Motors dropped the Hudson brand in 1957 and concentrated on making the compact Rambler models before it too was slowly bought up and closed down in the 1980s.

Back In the Garage… Way Too Soon

Our tour near Orange County’s John Wayne airport was leisurely, quiet and comfortable. The radio with its nice base could easily be heard even with the windows down. Given our car’s origin, I wondered whether we might hear something like, “Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a day that will live in infamy—Pearl Harbor was suddenly and deliberately attacked from the air by the armed forces of the Empire of Japan…” But then this car may have been a later one built in January or February before all auto production was halted in preparation for defense work.

The fact that our woody survived the war and the seven decades since that tumultuous time says a lot about the Hudson Motor Car.

We pull back into Crevier, and the big Hudson Woody glides inside the storage area in almost total silence, its long historical journey not yet over.