1934 DeSoto Airflow

In An Era Dominated By Boxy Automotive Designs, the Airflow Definitely Was Aerodynamically Ahead of Its Time. In Fact, It Looks More At Home On the Road Today Than It Did 85 Years Ago.

Avin Gebhard backs his impeccable 1934 DeSoto Airflow out into the sunlight. It’s a Brougham (what we would call a two-door sedan today) and is finished in sparkling metallic golden beige with brown fenders for accents. (And yes, they did have metallic paint in 1934.) The car is a combination of aerodynamics and styling elements that almost works aesthetically. Or to put it more succinctly, when viewed from a distance, the car looks a lot like a horseshoe crab.

The DeSoto, and especially the bigger, more luxuriously appointed eight-cylinder Chrysler Airflows, caused a worldwide sensation when they debuted in 1934, but they did not become the sales success that Chrysler had hoped for. It has been said that the cars were “too unconventional” for the times, when automobiles were generally upright and squared off, with little to no attention paid to aerodynamics or streamlining. This is only part of the story, but more on that later. First let’s take this unique brougham for a spin.

Ready for a Drive

The door is sturdy, wide and accommodating. Climbing into the Art Deco-style front seat is easy, though you have to cantilever your bottom over the chrome pipe armrest attached to it. The seat is sofa-like and is soft, comfortable and very roomy. I roll down the side window, and to my surprise, the vent wing goes down with it.

I depress the clutch, which is light, then twist the key and hit the starter. The 241.5-cubic-inch, 100-horsepower flathead six turns over a couple of times, comes to life, warms a little, and then settles into a smooth quiet purr.

The dash looks like that of an early Volkswagen Type 1 (Beetle), with two big easy-to-read gauges consisting of a speedometer/odometer and trip meter in one saucer-sized unit, and a temperature gauge plus ammeter, oil pressure and gas gauges included in the second equal-size instrument, making it easy to discern the health of the engine at a glance. I verify that all is well, and then let off the parking brake using the chrome pistol grip handle in the center of the instrument panel.

The big steering wheel is mounted almost straight up and down in front of you because the steering box is up in front of the front axle on this car, partially due to its short front end, and partly because the engineers at Chrysler knew that this position would make steering easier in this pre-power steering era because the more vertical position only involved your arms rather than having to get your back into it to turn the car. Chrysler’s engineers even consulted the Mayo Brothers, founders of the Mayo Clinic, on the ergonomics of the car, many years before ergonomics became a science unto itself.

I pull the shift lever down into low gear and we are off. The lever curves down and forward under the dash, and the shifter ends up close to the dash even in high gear, making it a fairly safe arrangement for a third passenger in the middle. Looking out over the hood is uncannily like looking out over the hood of a VW Beetle in that it falls away abruptly, leaving you with nothing but a clear view of the road ahead.

At Home On Today’s Roads

The engine is smooth and has plenty of bottom-end torque, so even though we are going uphill, acceleration is quite good for a car made 85 years ago. The transmission has synchromesh in second and third gears and shifts smoothly, so we are soon up to a comfortable cruising speed of about 50 miles per hour with the engine comfortably in its sweet spot.

Overdrive was not available on the DeSoto Broughams, but the coupes and four-door sedans did have it as an option. And so equipped, you could cruise on a modern freeway at or above the speed limit without drama.

In fact, the Chrysler Airflows with their big eight-cylinder engines are quite at home on modern freeways. I once drove a Chrysler Airflow four-door more than 30 miles at a steady 70 miles per hour, and I can attest to the fact that it felt virtually like a modern car. There was little wind noise, and handling was predictable.

Braking is not up to modern disc brake standards in terms of brake-fade on our ’34 DeSoto, but under normal conditions its vacuum-assisted hydraulic brakes work well and stop straight, with little pressure on the pedal. The appearance of these cars smacks of the Art Deco era of the 1930s and looks dated today, but they were way ahead of their time when it came to engineering.

An Engineering-Driven Company

Walter P. Chrysler was a veteran of the auto industry, having managed Buick for many years before he took over the ailing Maxwell Motors and morphed it into his own company in 1925. Chrysler’s initial offerings, including his namesake Chrysler, and later the DeSoto and Plymouth, were handsome, well-engineered and in the case of the Chrysler, fast too.

In fact, in the late 1920s, Chrysler model 72 roadsters raced at Le Mans, and the only cars that bested them were a Stutz that came in second, and the Bentley that won the race. Chrysler also bought Dodge in 1928 after the Dodge brothers finally succumbed to complications of the Spanish flu that had afflicted them a few years before.

Automotive Inspiration From the Sky

Fortified by his initial success, Walter Chrysler wanted to get ahead of the curve with an all-new car, and he had the engineering talent on staff to do it. During his brief stint at Willys, he’d hired his “Three Musketeers,” consisting of executive engineer Carl Breer plus Fred Zeder and Owen Skelton, away from Studebaker and they had been a big part in Chrysler’s success in the early years.

Engineer Carl Breer—as legend has it—was out driving one day and noticed a flock of geese flying overhead. It inspired him to consider what made it possible for them to go so fast with so little effort. And that got him into thinking about the aerodynamics of the automobile. He then enlisted the help of Orville Wright to build a wind tunnel. They tested over 50 scale models by 1930.

The results of their tests with conventional automobiles were startling. They discovered that the standard little box in front of a big box configuration actually generated less drag and turbulence when it was turned around backward! They also learned that a stubby, rounded front end generated less drag than a long squared-off one. And they discovered that a car that was wider in front and narrower in back was more aerodynamically efficient too. They also found that a tapered rear end developed less turbulence than one that was squared off abruptly.

Chrysler’s Cliff-Diver

To publicize their discoveries, Chrysler turned the body of one of their conventional models around backward on the chassis, and then drove the car on public roads to demonstrate the point. There is even a well-known publicity stunt photograph of a policeman giving the driver a ticket for going the “wrong way” down a street.

All of this newfound information was incorporated into the design of the new Airflow which was revolutionary in other ways as well. For example, the body of the car was entirely made of steel, and had an internal cage welded into a unit, making it stronger and lighter than the traditional wooden framework with sheet metal tacked to it that was standard at the time. The Airflows still had a light frame under them but the car depended on the unitized body for strength. The fenders were still separate and bolted on though, as was standard at the time.

The result of these innovations was a comparatively lightweight but very sturdy automobile. In fact, it was so sturdy that later in 1934 a Chrysler Airflow was driven off of a 110-foot cliff in Pennsylvania. It suffered minimal damage, and was righted and driven away. Film of this publicity stunt still exists, and you can find it on the Internet.

Other engineering innovations consisted of moving the engine forward over the front axle, and moving the passenger seating in front of the rear axle, making for a much softer ride. That, on top of Chrysler’s Floating Power rubber motor mount arrangement made for a very quiet, smooth, comfortable car. The Floating Power system consisted of two motor mounts down low in the rear, and one on a yoke high up in front that let the engine dance around without transmitting the vibrations to the passenger compartment.

A Good Car…At the Wrong Time

The Airflows were quite a sensation when they debuted in 1934 due to their startling appearance, but they attracted few buyers. Chrysler’s conventionally styled models far outsold them. In fact, the Airflow design almost resulted in the demise of DeSoto because unlike the Chrysler division, the marque did not have any conventionally styled models to offer as alternatives.

On top of that, there were the usual teething problems when any new model goes into production and first hits the road. Initially an engine or two shook out of the Chrysler versions of the Airflow at 80 miles per hour. The problems were quickly addressed, but they, along with the new look, scared many buyers away.

Another thing that hurt sales of the Airflow was that it came out during the depths of the Depression when unemployment was above 20 percent, and at a time when other luxury carmakers were going for broke trying to attract the few remaining buyers with stunningly beautiful offerings such as Duesenberg, Marmon, Pierce, Cadillac and Packard. The Airflows weren’t ugly, but they weren’t as elegant as the 1934 Packard or the Marmon V16 either.

This Design Worked Overseas

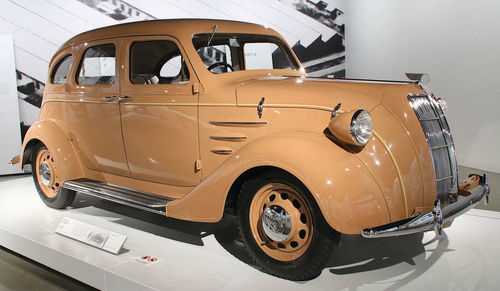

The situation in Europe was different though. Steyr in Austria, and Tatra in Czechoslovakia had been experimenting with aerodynamic designs thanks to Hans Ledwinka and Ferdinand Porsche since the late 1920s, and had produced some rather striking rear-engined, aerodynamically engineered automobiles that were credited with being the inspiration for the VW Beetle, though I believe the Airflow had more of an impact on styling than most people think.

It is undeniable that there was a great deal of parallel development in the automotive industry at that time, but the KdF Wagen, later dubbed the Volkswagen, that debuted in 1937 is a dead ringer for the 1934 Airflow coupe, and I doubt if that is coincidental. The bolt-on rounded fenders, sloping clamshell hood, split back window, the headlight placement, the dash, and the body profiles are uncannily similar.

Furthermore, the French Peugeot 202 that debuted in 1938, the Toyoda (Toyota) AA that came out in 1936 and the Austrian 1936 Steyr 50 I believe were all influenced by the Airflow design. And you could put the Italian 1937 Fiat Topolino in the mix too.

There is a difference between scientifically derived aerodynamics and what was commonly called streamlining. Streamlining was actually more of a styling gimmick in the 1930s that was applied to cars, locomotives and even buildings to make them look dynamic. I cite the mid-’30s Cords and Lincoln Zephyrs, the Cadillac LaSalles and the Burlington Zephyr locomotives of the time, as well as the Art Deco streamlined buildings in every major city that were rounded and had cornices that look like cooling fins on engines. Even toasters and vacuum cleaners became streamlined back then.

And speaking of cornices, the Chrysler building in New York that opened in 1930 has a cornice of Airflow-like fenders and wheels just below the big eagles at the corners where the building first narrows. Chrysler and DeSoto Airflows were obviously ahead of their time in terms of aerodynamic engineering, but sales might have benefited from a bit of streamline styling as well.

The Restoration Was a Major Project

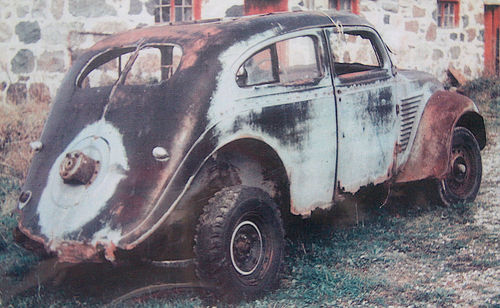

Al Gebhard’s 1934 DeSoto Airflow that we are taking for a spin is certainly proof of the car’s rugged longevity, because it went through a couple of lifetimes of hard work and total neglect in Canada and Alaska before anyone considered restoring it. Indeed, our example is as much a monument to the dogged determination and attention to detail of its restorer as it is to Chrysler quality and durability.

Most of its restoration was completed before Al bought the car, and a heroic effort it had been indeed. Its panels were rusted beyond what most panel beaters would deem repairable, and it was a dented, damaged derelict when it was rescued in Canada with huge snow tires mounted on it, and it appeared to be more like a dune buggy than a car.

Airflow engines originally came with aluminum heads to help with cooling, as did many other cars of the era, but they often corroded into place around the studs due to electrolysis, and were nearly impossible to remove without destroying them. When this car was found, the head had been removed and destroyed in the process, and studs had broken off in the block.

Rain had gotten into the engine too and it was stuck. But it was stripped and remachined, and a later cast iron head was found for it. These early Chrysler engines were state of the art for their time, with full oil pressure to thin shell bearings, and aluminum pistons, so once this example was overhauled it was ready for another couple of lifetimes of service.

More Than Design Was Ahead of Its Time

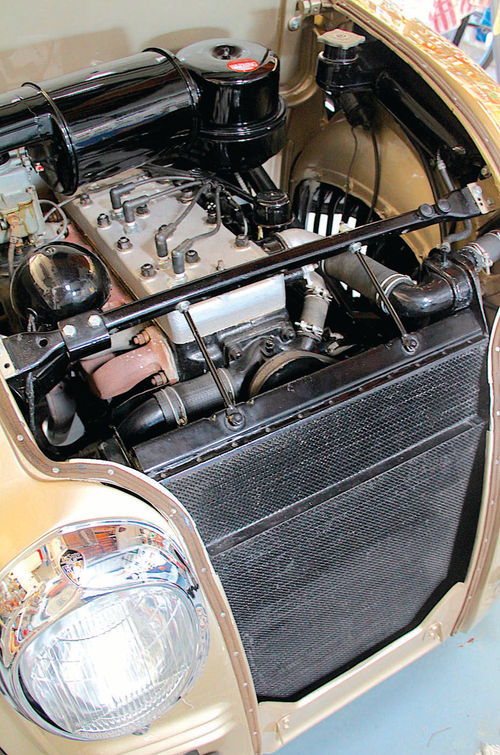

Chrysler engineers came up with several innovations that allowed them to use the sloping clamshell hood, unique to the Airflows at the time. The radiator slopes back, and its top tank is actually mounted longitudinally along the driver’s side inner fender. The air filter is also offset to allow for hood clearance. These ideas became common later, but were unique when the Airflow debuted.

The term “classic” in common use today originally referred to the Greco-Roman revival that influenced architecture in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It resulted in banks that looked like the Greek Parthenon, and government buildings that mimicked the Roman Pantheon. The classic style also carried over into automobile design with RollsRoyce’s Parthenon grille, still in use today, as well as Packard’s Perpendicular Gothic tri-foil church window grille.

However, the way historians use the word generally is to refer to design thinking that was a breakthrough in its day, and that influenced the future. In that sense, the Airflow is a true classic because it was revolutionary, and it had a huge influence on the future. Even today, it looks like a car that would have come later than most of the cars of the 1930s rather than before.

Smooth, Quiet and Enjoyable

Driving through the picturesque hills of the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Southern California on a nice day in a smooth, quiet, unique classic car with the windows down and people looking up from their gardening occasionally to smile and wave is about as good as it gets.

Although its flathead six cylinder engine, three-speed transmission and solid axle front suspension were not revolutionary at the time, the car rides and drives like a modern one, and pulls well without a lot of gear changes. It must have been very impressive in 1934, and still is today.

The fresh seaside air wafts through the crank-out twopiece opened windshield and comes in through the twin cowl vents that allow both driver and passenger to adjust air circulation. There are also pivoting wind wings in the rear to let air out, making for a very comfortable situation on warm days.

But our time is running short and the sun is setting, so we wheel the car back into Al Gebhard’s garage and park it next to his Morgans and other British classics.

It has been a rare and delightful experience to drive his DeSoto Airflow and to experience for ourselves just how enjoyable these cars were then and now.

1934 DeSoto Airflow Specifications Base Price: $995

Engine

L-head straight-six; cast-iron block and aluminum head

Displacement: 241.5 cubic inches

Bore x stroke: 3.375 x 4.50 inches

Compression ratio: 6.2:1

Horsepower @ RPM: 100 @ 3400

Torque @ RPM: 185-lbs. ft. @ 1200

Valve train: Solid valve lifters

Main bearings: 4

Fuel system: Ball & Ball single-barrel downdraft carburetor

Lubrication system: Full pressure, gear-type pump

Electrical system: 6-volt

Exhaust system: Cast-iron manifold, single exhaust

Transmission

Three-speed manual

Ratios

1st: 2.59

2nd: 1.49

3rd: 1.00

Reverse: 3.24

Differential

Type: Spiral-bevel gears; semi-floating rear axle

Ratio: 4.11

Steering

Worm and roller

Brakes

Hydraulic; steel drums

Front/Rear: 11 x 2-inch drum

Chassis & Body

Construction: Bridge-truss frame with semi-unitized body featuring integral space-frame and all-steel body

Body style: Two-door Brougham

Layout: Front engine, rear-wheel drive

Suspension

Front: Tubular one-piece axle; longitudinal semi-elliptic leaf springs; hydraulic lever shocks

Rear: Solid axle; semi-elliptic leaf springs; hydraulic lever shocks

Wheels & Tires

Wheels: Stamped steel discs with drop-center rims

Tires: Front/rear: 6.5 x 16 inches

Weights & Measures

Wheelbase: 115.5 inches

Overall length: 197 inches

Overall width: 71 inches

Overall height: 66.5 inches

Front track: 57 inches

Rear track: 56.25 inches

Weight: 3378 pounds

Capacities

Crankcase: 6 quarts

Cooling system: 19 quarts

Fuel tank: 16 gallons

Transmission: 4.5 pints (with overdrive)

Rear axle: 4 pints

Performance

Top Speed: 86.4 mph