Hey, What’s Hiding In Those Shrubs?

Let’s Follow Along as These Folks Track Down Some Great Cars & Trucks.

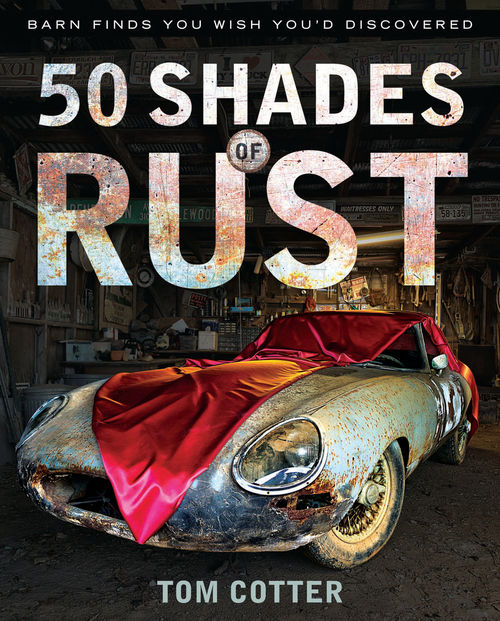

Editor’s note: Some folks now choose to call it “automotive archaeology” but it’s still the pursuit of a car or truck that’s been dormant for years in a remote corner of an aging storage building or deteriorating under the onslaught of outdoor elements in an untended farmer’s field. You might think of them as “barn finds,” but whatever term you use, they represent a constant lure in the vintage vehicle hobby. The following are excerpted from “50 Shades of Rust” by Tom Cotter, and who knows, they may cause you to drive a little slower the next time you find yourself on a remote country road.

Foreword—Rust Never Sleeps

By Wayne Carini, host of Chasing Classic Cars

Rust and classic cars have a complicated relationship. Rust can be the bane of the car owner’s existence— extensive rust can drive a car to the junkyard or to expensive re-fabrication and restoration. Rust can render a car dangerous to operate. Even a spot of rust can spell doom to a car owner as it can spread quickly and without regard for make, model and year. For all of the pain that rust can cause, though, it can also tell the car collector a human story about the lives of the people who drove the car, where they lived, what they did, and what their particular brand of life was like.

In the early days of the automobile, rust was a nuisance, an embarrassment, a cancer that had to be removed. Rust removal did not begin as a concern for the aesthetics of the car but as a utilitarian enterprise. The average automobile was the second largest investment for a family besides a house; it had to last a long time. Early car owners repaired their cars so that the drivetrains could survive long enough to get them from point A to point B. Families did not take their cars in to trade them up for the newest model like we do so often today.

The ’40s and ’50s saw the birth of the collector car hobby as we know it. Full restoration was in vogue. The mindset in those days was to present a car that looked better than it did the day that it rolled off the assembly line. My father, Robert Carini, began his long career in automotive restoration with a Model A Ford that he found behind a barn in a small Connecticut town. He made that car look brand-new, and along with two other friends, founded the Model A Restorer’s Club of America.

When my father restored a car, he did it to absolute perfection. From a young age, I helped him in the shop. Whichever car he was working on— be it a Packard, Duesenberg, Buick, Lincoln or Ferrari—it had to be an award winner. Every year we would pack up and head from Connecticut to Hershey, Pennsylvania, the Mecca of the collector car hobby, with our latest work in tow. These were both exciting and stressful times. Everything about the car we brought had to be absolute perfection. We went as far as to take a jack to the car show, jack the car up, and rotate the wheels so the name on the hubcap was perfectly horizontal and the valve stem was pointed straight up. I cannot recall a time when my father didn’t take home a trophy.

For my father, restoration was the ultimate joy in the classic car business. He lived for the details, for giving an old wreck a new lease on life. Being witness to such perfection, and getting a chance to learn hands-on, has been incredibly formative to me and to my work. I too love to restore a car to absolute perfection, but I find myself being drawn to old barns and garages. Maybe I’m lured by the promise and hope of complete originality, the excitement of finding a piece of history, frozen in time. I don’t fear rust—in fact, rust is in itself beautiful, a badge won for a car’s survival. My television show, Chasing Classic Cars, has given me the unique opportunity to share this passion with viewers. I feel as if I am on a constant treasure hunt for rusty gold, and I’ve never had more fun.

Tom’s books perfectly capture the unhindered joy of what we’re now calling automotive archaeology. There’s something about finding that car, hearing the stories, and getting a glimpse into not only an automotive history, but also the personal history of the previous owner— it’s intoxicating. From all the time that we have been collecting and restoring cars, we have finally caught on to what art collectors have known for years. The piece of art, or in our case the automobile, should be treasured for what it is, in the condition that it is in. If the car shows a little sign of rust because the paint has been worn through, that’s all the better. If the interior is worn and the seats have a bit of a tear, it should be left alone. Now we say that these cars have a “patina.” Cars with patina tell a story, much like works of art. This has caught on so much that there is now a preservation class at Pebble Beach. Rat Rods are being built out of rusty old car parts and enjoyed by a whole new type and generation of car collector. Cars with surface rust on them are being clear coated to preserve the rust. Things certainly have changed in the past few years. Rust is finally in!

There is always a fear in the back of my mind that we’re going to run out of cars to find, that soon every barn will be without rusty gold, but every time this fear rears its head, I’ll get a call or an email about a barn full of cars, and I’m on the chase again.

Chapter 5 The Hidden Holman-Moody

Even the most dedicated car restorer would probably have ignored the rusty hulk that John Craft discovered in a Virginia field.

It was obviously some sort of stock car—probably 1960s vintage—but it was so badly rusted that it would have been a shame to halt the ashes-toashes, dust-to-dust cycle it had begun.

But to Craft, a PhD, lawyer, and professor (but mostly a renowned stock car racing historian and author), he had just stumbled upon a piece of gold. Craft specializes in vintage Ford stock cars built by Holman-Moody. He had already found and restored a couple of Holman-Moody cars.

“This car was dumb luck,” the Texas resident says. “I never thought I’d find another Holman-Moody car.”

How Craft came to know of this car was a fluke. “I was on a scale car model builders’ forum,” he says. “And someone started a thread: ‘Wonder whatever happened to all the old cars?’ Then another guy sent in two photos: one of a car in a field, and the other of the Holman-Moody ID plate.”

It was a 1964 Galaxie, originally manufactured at Ford’s Norfolk, Virginia, assembly plant. The “roller” was delivered to Holman-Moody in Charlotte, complete with interior and windows but minus engine and transmission. The car was then converted to NASCAR racing specs at Holman-Moody and painted George Barris Candy Apple Tangerine.

The Galaxie was raced by Skip Hudson (Riverside), Bobby Marshman (Daytona 500), Augie Pabst (Sebring support race), and Larry Frank (Atlanta 500) in 1964. It was then sent north to race in USAC.

In 1965, it returned south and served as Jabe Thomas’s NASCAR rookie ride. When Ned Jarrett lost his team car to a transport accident that season, Thomas rented the car to him at Nashville. Thomas used the car again during the 1966 Grand National season before it was put out to pasture.

“At the end of the 1966 season, Thomas brought the car to a field, stripped it, and there it sat for 41 years,” Craft says. Craft asked the owner if he’d consider selling. The answer was yes, and a comprehensive restoration was begun.

“The chassis needed lots of work,” he says. “I was able to salvage the frame, lower control arms, and pedals. It was rumored that H & M used ‘chemical milling’ and other lightening techniques to keep pace with the Hemis in 1964. That is possibly one reason the car was in such bad shape; that and Thomas wrecking a lot.”

Using bodywork from a rust-free Arizona 1964 Galaxie, the restoration is nearly complete. The car was recently hand-lettered in the original Holman Moody style by NASCAR archivist Buz McKim. When completed, Craft hopes to race the Ford in vintage stock car races at Sebring, Florida, and Laguna Seca, California.

An interesting note: Just before Craft purchased the Ford from the field, another stock car that had been resting next to it for many years was crushed. “It was Richard Petty’s 1969 Plymouth RoadRunner,” says Craft. “The only thing that saved this Ford from being crushed was the tree that had grown through the engine compartment.”

Chapter 41 Star-Struck Roller

For some folks, it was The Honeymooners. For others, it was Star Trek or Batman. For me, it was Leave It to Beaver. For so many of us of the Baby Boomer generation, there seems to be a favorite television show that we remember for decades after the show ceased to be shown. For Jim Inglis, it was Burke’s Law.

Burke’s Law starred Gene Barry as millionaire Amos Burke and featured his faithful chauffer, Henry, and their unusual “squad car,” a 1962 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II. The story revolved around Burke, who even though rich, took the job of being chief of homicide in the LA Police Department. The car played a significant role as it chased down criminals. It even had an onboard telephone, which was quite a novel idea in the 1960s. Inglis never missed an episode, and the theme song stayed in his head into adulthood.

“When I got older and started to collect cars, I sought to find the whereabouts of the Burke RollsRoyce,” says the Florida resident. “But California-based Four-Star Productions, who produced the show, was long gone; tracing the license plates proved fruitless; and star Gene Barry was living in a life-care facility.”

But Googling Burke’s Law RollsRoyce put Inglis in touch with a trail of former owners. When the trail ended, the car was in a garage in Vero Beach, Florida, just 60 miles north of Inglis’s Palm Beach home.

After a short negotiation, he owned the Rolls.

“After 45 years, my long-awaited dream has come true,” Inglis says. “It’s a 35,000-mile original car, and that’s just the way I plan to keep it.” Case closed!

Chapter 45 Leno’s Voluptuous Vette

Jay Leno has the same reaction to great finds as I do: nothing gets him more stoked than when he discovers another cool old car or bike.

Lucky for me, whenever Leno acquires another barn find, he gets so excited that he calls to tell me about it. Certainly one advantage Leno has is being one of the most visible car collectors in the country, if not the world.

The former host of the Tonight Show receives lots of letters from people who want to share stories about their cars. Leno said that he personally reads every letter, usually grabbing a handful from the mailbag on the way to lunch.

“So I grabbed an envelope from a guy in Michigan,” he says. “People in Michigan live around cars, so I thought it might be something interesting. The letter said that this man wanted to sell me his 1963 Fuel-Injected Corvette.”

Leno almost choked on his sandwich. “I’ve been looking for a fuel-injected Split Window for so long,” he says. “But it had to be the right car.”

This was the right car. The 1963 Corvette was the first model Sting Ray, known as second generation, or C-2. It was designed by Larry Shinoda with input from Peter Brock and under the direction of Bill Mitchell. At the time, the distinctive sloped rear roof design was a styling breakthrough. However, the rear window was divided by a roof support, which meant the driver had an obstructed view from the inside rearview mirror.

But despite Father-of-the-Corvette Zora Duntov’s protests regarding the rear window design, Mitchell insisted that it remain. And it did for just one year.

Besides being the first Corvette with hide-away headlights and fully independent suspension, 1963 coupes are especially coveted today for their unique rear window styling.

The details of the split window got juicier—the seller said the Vette had just 991 original miles on the odometer!

“The story was that the original owner ordered it, then shipped off to Vietnam,” Leno says. “When he got out of the service, he did something that got him in trouble, and he went to prison for 20 years. While he was in the slammer, his grandmother sold the car to a collector, who then sold it to Russ McLean, Corvette Program Manager,” he says. “Nobody ever put any miles on it.”

Leno explains his Corvette is better that he even hoped for. “It’s equipped exactly like I would have ordered one in 1963,” he says. “It has power brakes, roll-up windows, and a four-speed.”

He had the car inspected by National Corvette Restoration Society (NCRS) members, who confirmed the car’s authenticity. “The car is matchingnumbers correct, has the correct air cleaner, the correct master cylinder, everything,” Leno says.

Leno admits that with only 991 miles on the car, he won’t drive it much. But he is a car guy, and he drives all his cars. So this car will get a few miles on it from time to time.

“It drives like a brand-new car,” he says, smiling.

Chapter 68 Check Out the Block On This One

As a young guy in the 1960s, what could be cooler than to own a big-block Chevy? Nuttin! So in February 1969— when Chick Renn of York, Pennsylvania, was 20 years old—he went down to Ammon R. Smith Chevrolet in his town and, with just $25, ordered a brand-new, dark green 1969 Nova, complete with a 375-horsepower 396 L78 engine, Turbo Hydra-Matic, bucket seats, console, gauges, the works.

The only problem was that he had to wait until he turned 21 to apply for the loan.

On April 17, 1969, one week after his 21st birthday, he signed the loan papers and drove the car home. Recently married, his wife, Karen, drove the hot Nova back and forth to work for a couple of years. Then, in 1972, Renn took the Nova off the road for the occasional drag race. “I never wanted to hack up the metal, so I never installed a roll bar,” said Renn, now 65. “I only modified the torque converter, added headers and slicks, things like that.” Then, the car sat. And sat.

In 1983, with just 24,700 miles on the odometer, Renn sold his beloved Nova to a man in Poughkeepsie, New York. That man sold it to a man in Massachusetts who sold it to a man in Pennsylvania, who sold it to a man in Ohio.

In 2011, Renn got a call from a friend who was attending the GM Nationals at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. “Hey, Chick,” his friend Skip Lecatas says, “I just met the guy who owns your old Nova!”

Lecatas gave the owner Renn’s phone number, and the man promised to call because he wanted some old photographs of the Nova for his show display. One year later, the man finally decided to call Renn. “Hey, I’m going to display your old car at the GM Nationals this year,” the owner said. “Why don’t you come down and take a look?”

So Renn drove to Carlisle

“It’s 2012, and it’s the first time I’ve seen my old Nova in over 29 years,” Renn says. The two men talked for a couple of hours, and as he was leaving, Renn turned to the man and said, “If you ever decide to sell, let me know.”

One year later, in June 2013, again at the GM Nationals, the two men talked again, striking a deal for the Nova. “I bought my old car back,” Renn says. “After selling it 30 years ago with 24,700 miles, when I bought it back, it only had 31,849 miles.

“Even got back my old 1972 license plate that was on the car when originally sold and all my old paperwork,” he adds, “including my old title, owner’s card, Ammon R. Smith order form, and bill of sale, warranty, P.O.P, and 1973 registration sticker.

“The car’s in great shape and still has the original paint, engine, and drivetrain. We’re just going to drive and enjoy it. This time,” Renn notes with relief, “it’s staying in the family.”

Chapter 87 Earnhardt’s Dumper

Lars Ekberg invited me to his home in North Carolina to show me his great cars, some of which were barn-finds. As we walked from garage to garage, we kept passing a big old Ford dump truck, nasty and neglected. I didn’t pay any attention to it.

As I was about to say thank you and goodbye, Ekberg said to me, “You know, that old truck has an interesting story. It used to belong to Dale Earnhardt, Senior.”

I stopped in my tracks. “Can you tell me more?” I asked.

“My buddy Jimmy Sides went to school with Dale,” he said. “They were lifelong friends.”

Ekberg explained that Earnhardt had owned the 1967 F-600 truck for a long time and had used it at his nearby farm in Mooresville, North Carolina, to haul around hay for horses. Sides bought it from Dale about 20 years ago to use when feeding his own horses, but parked it in a barn about 15 years ago and never took it out again.

“When Jimmy passed away in 2010, his wife called me up and asked if I wanted the old truck,” Ekberg said. “She gave it to me. The title is still in Dale’s name.”

So there the truck continues to sit, last inspected in 2000. Ekberg is undecided what he will do with the old relic. But one thing is for certain—he owns the world’s largest Dale Earnhardt souvenir.

Chapter 93 Push the Bush For a Superbird

Barry Lee is brilliant. The motorcycle dealer from Jacksonville, Florida, disguised a barn-finding adventure as a romantic weekend with his wife at a casino in Biloxi, Mississippi. Lee had heard of a rare and desirable Plymouth Superbird behind a house in Alabama, which he could visit en route.

“I told my wife we would go gambling over Christmas,” said Lee. “She was all for it!” Lee’s profession is two-wheelers, but his passion is very fast four-wheelers of the Mopar variety. He had already owned a number of big-block ’Cudas, Super Bees and Challengers, but his dream was for one of Chrysler’s high-winged models: the Superbird or its cousin, the Dodge Daytona, cars designed to compete on NASCAR’s superspeedways with drivers like Richard Petty and Bobby Allison.

He heard from an unreliable source about a Superbird that had been sitting behind a house near the Gulf Coast since 1975.

After a terrific holiday weekend of gambling, the happy couple drove through the coastal Alabama town and to the address where the automotive treasure was supposedly sitting.

The house was obviously abandoned, and the property was littered with old trucks and cars, but there was no Superbird. Lee was beginning to think his friend was pulling his leg when his wife noticed an orange object inside a nearby bush. When her husband pushed aside the branches, it revealed the car of this dreams—a bright orange, 1970 Plymouth Superbird. Parked in the same location for three decades, a hedge had actually engulfed the car.

Lee found out who owned the house and called the phone number. “Whenever I called and said I was interested in the car, the person on the other end hung up the phone,” said Lee.

It turns out the elderly owner, Frank Moran, whose wife was in a nursing home, lived nearby with his daughter.

So Lee’s wife stepped in again and suggested they simply write a letter that stated their desire to remove the car from the elements and restore it like new.

At least a year passed before Lee received a surprise phone call from Frank’s son-in-law, George Proux. “Frank fell and is in the hospital,” Proux said. “I have power-of-attorney and had all the cars and trucks hauled off before I found your letter.

“The Superbird is sitting at my house in Jacksonville, Florida.”

What a coincidence that it should actually be just a few miles from Lee’s own house.

Lee carefully inspected the car. It was equipped with a numbers-matching 440-cubic-inch engine, automatic transmission and bench seat, and still wore its original Goodyear Wide Oval tires on rally rims.

It was one of only 1920 Superbirds that year, and incredibly, this one had less than 1000 miles on it.

The son-in-law had planned to restore the car, but after surveying the severe rust damage, he reconsidered.

Lee arrived at just the right moment: he had driven his own 1970 lime-green Road Runner, which attracted Proux’s attention.

The two traded cars and Lee now owns possibly the lowestmileage Superbird on the planet. A major restoration is in progress.