Feature Restoration 1970 Corvette

If You Found a Project Car “In a Million Pieces,” What Would You Do? This Restorer Found That The Result Was Well Worth the Effort.

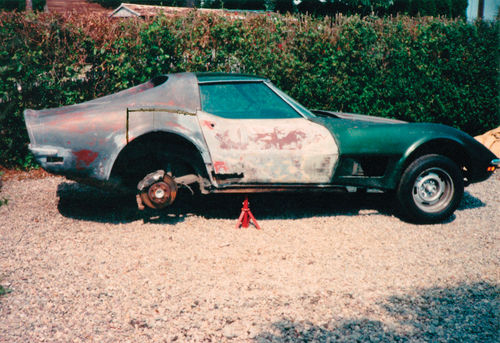

Once Dave Thomas saw the 1970 Corvette that had been advertised for sale, he quickly realized the scope of the project awaiting him if he bought it.

“I found it in a guy’s backyard in a million pieces,” he recalled. “It was the proverbial basket case, so to speak.”

That was in August of 1996 and the Corvette’s immediate story to that point was a sad one. The odometer showed 98,000 miles, 12,000 more than it had read when the seller had purchased it to begin his try at a restoration.

“He had owned it for eight years,” Thomas explained, “and he lost his restoration facility and kind of gave up on the car. He brought it home, put it in his yard and it stayed there.”

That’s certainly not the only example of a project that was halted by developments beyond the control of a car’s owner, just as it’s not extremely unusual that a new owner would be willing to take on the work. In this case, Thomas said the Corvette is a matchingnumbers car, but even if it were unable to make that claim, it probably would have stood a good chance of being restored.

After all, Thomas knew what he was looking at on that day in 1996. But it’s difficult today to grasp the surprise that must have been felt 43 years earlier by those seeing their very first Corvette.

Chevys Had Been Designed With Families In Mind

Chevrolet, to put it gently, did not have a reputation for sizzling performance in the early ’50s. It had resumed production of civilian vehicles after World War II by following the industry-wide approach and reintroducing its last prewar model from 1942 as its first postwar model for 1946. The two were not identical, of course, but the new car’s changes were the equivalent of an annual update so that the car probably was what a Chevy would have been in 1943 if not for the war.

When the 1949 models arrived as Chevy’s first real postwar cars, they were impossible to miss and more importantly, they were also impossible to mistake for their predecessors. True slabsided design was still a few years away, but Chevrolet was heading in that direction. Advertising promised that “your eyes will tell you that its lines, colors, fixtures and fabrics identify it as the beauty leader of 1949.”

Chevy next boasted that it was “Startlingly new! Wonderfully different!” for 1953 and while that wasn’t completely accurate—the 1952 body had actually been given a facelift—it did look that way. The vestigial rear fender was still there and making its last stand, but it now raised the taillight to the level of the beltline. The sheet metal’s details continued to move toward a wider look and the overall package was attractive, but the world was changing, especially under the hood.

Faulting Chevrolet’s quality was difficult, but it still relied on a six in the face of an unmistakable V-8 future. Cadillac and Oldsmobile four years earlier had introduced what would become a standard design, the oversquare (cylinder bore larger than the piston stroke), overhead-valve V-8. Buick, Chrysler, DeSoto, Dodge, Studebaker and Lincoln followed with their own V-8s by 1953 and Ford and Mercury would do so in 1954, while Chevy’s was still two years away. Meanwhile, it touted its “two great high-compression engines,” the 108-horsepower ThriftKing and the 115-horsepower Blue Flame. Each was an overhead-valve six, a design for which Chevrolet was long known and widely appreciated, but not up to the task of changing Chevy’s image to one of anything beyond that of a solid family car.

From a Show Arena to the Showroom

Chevrolet had been working on a solution to its image problem and the result appeared at GM’s Motorama in January of 1953.

The two-seat Corvette show car rode a wheelbase 13 inches shorter than that of a production Chevy. It was low and clean with such exotic features as bumperettes more decorative than useful, screened headlights and wheelwells large enough to completely reveal the tires. Under the hood was Chevrolet’s only engine, the faithful inline six, and careful tweaking gave it a substantial boost of 45 horsepower so that it now generated 150 from 235 cubic inches. That engine was no real liability in 1953 as other sports cars relied on fours and sixes, but the twospeed Powerglide automatic transmission probably raised the eyebrows of a few purists. Still, that didn’t matter because the Corvette was only a show car conceived primarily to reflect some of its glory onto everyday Chevrolets.

There was a problem, though, in that it quickly proved to be more than just a design exercise or marketing tool.

Chevrolet was able to advertise with a straight face that it had met with “a storm of enthusiastic approval” and in retrospect, hinting that it was a “preview of things to come” was a smart way to buy time while working out the details of building the Corvette. That had been planned as a possibility and thus didn’t come as a total surprise, but it’s to Chevrolet’s everlasting credit that it was able to build the first production Corvette on June 30, 1953. Only 300 were completed before the 1954s were introduced and like those cars in the first run, they looked almost exactly like the show car. All were white fiberglass with black convertible tops and red interiors and all offered something that few other sports cars of the day could offer, the easy availability of parts and service. Remember, it was a Chevrolet.

A Struggle That Provided Results

It almost wasn’t enough, though, as Corvette sales simply were not taking off with 3640 sold in 1954 and then a mere 700 in 1955 despite the availability of the 265-cubic-inch Small Block V-8. Chevy gave the car one last chance in the form of the restyled 1956 model which brought the look up to date and for the first time provided roll-up windows along with exterior door locks and handles. The 265 could now be ordered with up to 240 horsepower and the automatic transmission was at last made an option with a three-speed manual as standard equipment, clearly right moves in light of the resulting 3467 sales. A 283-horsepower 283 followed in 1957 and another restyle arrived for 1958 in the beginning of a pattern that would be followed for decades. Corvettes would no longer be basic sports cars like some of their imported contemporaries and would instead be performance cars that would gradually encroach on the territory of the exotics.

The Sting Ray Made a Definite Statement

While the 1958 restyling gave the car a number of features in keeping with the time—non-functional louvers on the hood, for example, and chrome strips on the deck—1963 brought the Sting Ray, a design unlike anything else on the road. While it continued the rear clip that had appeared in 1961, there was nothing else that even hinted at earlier Corvettes. The headlights were hidden, chrome was dialed down and lines were for the most part straight and smooth. It looked great as a roadster and equally great as Corvette’s first fixed hardtop, the one that would forever be known as the Split-Window. The unique backlight obstructed rear vision and didn’t return for 1964, though, and with other annual changes, the Sting Ray lasted through 1967. It then was replaced by yet another totally new look, this one based on the Mako Shark II show car, that heralded the beginning of the “designer” age.

The Corvette was now longer and stood out not because of flash, but because of its shape. Bulges rose above the front wheels and bracketed a hood that sloped downward to a thin chrome bumper separating the hidden headlights from the grilles below. Corresponding bulges over the rear wheels trailed back to a slight spoiler above a flat panel holding the round taillights. A subtle crease ran the length of each side to tie the front and rear bumpers together and in coupe form; the sloping B-pillars hid a roughly vertical—and removable—rear window. Advertising spoke of the fourwheel discs and independent suspension as well as “windshield wipers concealed by a power-operated cowl” and highback buckets. The base engine was a 300-horsepower 327, but those who preferred more could opt for the 427 with its 435 horsepower to make what amounted to the ultimate statement.

The Start of a Major Project

After all of that, changes for 1969 were minor and even those for 1970 were mainly evolutionary. Chevrolet advertised that “it’s not really a whole lot different looking. But in 17 years, we’ve never changed it just to change it.” There were changes, of course, and visually, the big ones were in the redesigned grille and fender louvers while the engine choices now topped out with a 460-horsepower 454.

Dave Thomas’ feature car isn’t quite that outrageous.

“It’s a 350 with 300 horsepower,” he said, “the base engine, with the automatic transmission. It’s kind of rare for that year; they only made 5108 cars with automatics in them.”

The car ran when he found it, although not very well, and he decided to take no chances with the engine.

“You could start it,” he explained, “but it was a really rough idle because all of the vacuum lines were disconnected and just lying there. I did remove the engine and had it rebuilt. It’s .030 over with a mild cam in it. The original intake was ported and polished, the heads were ported and polished; the carburetor was rebuilt. Basically, I put a little more horsepower into it than what it originally had…but it’s still civilized.”

It Was the Right Car at the Time

The engine-rebuild was one in a series of wise decisions he made on the way to the restoration’s completion, but there were those who didn’t see any wisdom at all in his decision to buy the car in the first place. Remember, he used “in a million pieces” and “proverbial basket case” in describing what he’d found in that backyard in 1996, a time when he might have purchased a nice example at a reasonable price.

“Oh, yeah,” he laughed. “Everybody was saying ‘you’re nuts.’ ‘You’re crazy.’ ‘You shouldn’t buy that.’ ‘You’ll never get it done.’”

They were wrong, of course, but maybe not totally wrong and besides, they didn’t know the whole story about another Corvette that Thomas had found at a dealership where it was priced far too high.

“I said ‘well, I can’t do that right now,’” he explained. “Then I found the one in the basket and it was affordable. For my budget, my timeframe, it was excellent. The car was put together with income tax money, bonus money and overtime money. And any change in the dryer…

“It took me five-and-a-half years to get the car done and in paint and back on the road because I wasn’t working 24 hours a day.”

He also wasn’t one to jump into the project without thinking it through and doing the necessary research.

“It was the first time I’d ever approached that type of car,” Thomas said, “and I had a little bit of learning to do, a lot of reading and a lot of parts trips down to Carlisle. I’ve got 24 years at Carlisle in Corvette parts shopping and that’s how I learned.”

The Carlisle swap meets are only a few hours from his Moosic, Pennsylvania, home, an advantage not every Corvetteowner has available. As mentioned above, there’s also the critical fact that a Corvette is a Chevrolet and when that potentially perfect match becomes available, there’s no denying the value of the lineage.

“Basically, you’re looking at a Small Block Chevy,” Thomas said, “so that’s a no-brainer. You take it for a ride and see how it handles, see how it sounds, how the transmission works…there are lots of people out there who know. Any good shop, if you have somebody at a shop that you take your vehicle to all the time, he would know, especially on a C-3 style. Even the early C-4s, the ’80s into the ’90s, there are so many things that are known to the mechanics as going wrong with the cars.”

Shopping for This Corvette Generation

The C-3 series dates from 1968 through 1982 and covers all of those Corvettes looking about like his car, while the C-4 runs from 1984 through 1996. From experience with his own car and from those 24 years of Corvetteshopping at Carlisle and elsewhere, Thomas knows what he’d keep in mind if he were looking for another C-3.

“The earlier C-3s are very hard to find,” he said. “You’ve got to go to a late C-3, maybe ’78 up. Those are out there.”

Assuming the choices pass the test drive and the basic walk-around inspection, much of what Thomas recommended looking at is under the car and begins with the brake calipers.

“They start leaking and that’s it,” he said. “You look at the back side of the wheel and see whether there are any drips on the back of the wheel.”

The leaks don’t often lead to catastrophic failure, he said, but they need to be addressed, something he guessed that he’s done about six times on the feature car. Fortunately, he hasn’t had to face another problem that’s equally hidden from a casual look, a rusted frame. The section from the rear axle to the end is a likely trouble spot, he said, but the entire frame should be inspected carefully.

“My friend had a ’76,” Thomas said. “It had a Swiss cheese frame. He put a new frame under the car.

“It was total Swiss cheese. He never knew it until he got it up on a lift. He bought the car and drove it as it was. Then he was getting work done on it and he had it up in the air because he was changing the exhaust to the side pipes and the guy said ‘your frame is shot. This car is unsafe.’”

The 1976-82 Corvettes, he said, use metal floorpans that are also susceptible to rust.

“Most of the guys POR-15 them to seal them and try to retain the original ones,” he explained, “but they are replaceable. It’s a very light piece of metal and it just rots to death. It rots right out and you’ve got a Flintstone mobile.”

His Corvette has a fiberglass floorpan and so he didn’t have to deal with that problem, but he did have to replace the rearmost body mounts.

“The number four mount is the most exposed,” Thomas said, “and so most of the garbage that gets in just lies there. There’s a gap of about a half-inch where it mounts to the body. It’s actually a fiberglass pin that comes down like the bottom of a table leg and the mount goes up over it. The bolt goes through the hole and they rot out, so I replaced both of mine. Mine were shot.”

The front crossmember and radiator support can rust, too, and that had been a problem on his car.

“I replaced all of that on mine,” he said. “The gentleman who owned it before I did found damage that was repaired. It was actually that somebody hit something with it or it got hit because that front support was rotted so badly that it pulled when it got hit. The suspension was there, but it was completely rebuilt.”

Parts Searches Aren’t a Problem

Beyond that, there was the bodywork, not all of which was just repairs to panels.

“There’s a complete new nose,” Thomas said, “everything from the cowl out including the radiator supports, the wheelwells, everything you’d need to complete the whole front end of the car. Basically, I peeled the front end off. It had a lot of parking-lot damage from using it and being driven, cracks in the wheelwells and stuff like that from people hitting it with their doors. The car was used. It was driven.”

That included the complex process of aligning and adjusting the front clip and hood, but there were the necessities that would be a part of nearly any restoration.

“Brand new wiring harnesses, new hoses, all the vacuum,” Thomas said. “I did the alternator because it was available for $100. I did my water pump because it was available for $100. My starter? They want $600 or $700 for a starter. I’ll probably never do it unless I find one that’s shot and I can get it done.”

The fact that he could buy those parts is an example of one of the great pluses to restoring or simply owning a Corvette like Thomas’ car. There’s likely no problem that someone hasn’t already experienced and solved and there’s almost nothing that’s not available to rebuild the car or just keep it on the road.

“You can buy a new frame,” Thomas said. “You can buy it complete or you can buy it stripped and put your own parts on it.”

And you can buy the smaller pieces, too, from the fiber optics that confirm the headlights’ operation to the small clips that hold the windshield-washer tubes in place. Since it’s a Chevy under the skin, of course, tune-up and maintenance parts are everywhere.

A Different Corvette Is Still an Option

He’s driven the car about 25,000 miles since its restoration was completed and said that once in a while, someone who sees it while he’s filling the tank will guess the year correctly. On the other hand, he said that nearly everyone is stumped by the Donnybrook Green paint.

“Absolutely,” he laughed. “The first thing they’re going to notice is the color. That’s the biggest thing. ‘Is that the real color for the car?’ ‘Yeah, that’s actually the real color.’ People say ‘well, I’ve never seen a green one before.’ ‘Yeah, well, here it is.’”

After owning it for more than 20 years, he’s not likely to let go of the feature car, but it could happen if the right 1963- 67 Corvette—a C-2—came along at the right price and at the right time.

“That’s the only way,” Thomas said. “If I could find the proper C-2, I wouldn’t even worry about selling this one. I would put it up later. I would still hang onto it when I had that earlier one in my hands and started on it.”

A lot of Corvette people would acknowledge that with a knowing nod. The 1970 ad mentioned above may have provided one of the best explanations ever of a Corvette’s appeal and its split personality when it spoke of “the Corvette idea. It’s still a car that’s built for the person who drives for the sheer excitement of it. For the driver who enjoys the true feel of the road. Yet it’s still a car you can drive at 10 mph in a traffic jam.”

The feature car’s previous owner probably understood “the Corvette appeal” when he owned it and was reminded of it when he saw the car on the road.

“When it was done,” Thomas recalled, “I took it down to him and it was slapthe-head and ‘Oh, my gosh. I should’ve kept the car and done it.’”