The Case of the “Imprisoned” Pontiac, Pt. 2

Once the 1950 Wagon Was Freed From Its Shed, Loading It Up Was a Struggle. After the Trailer Trip, It Was Time to Examine This Prize.

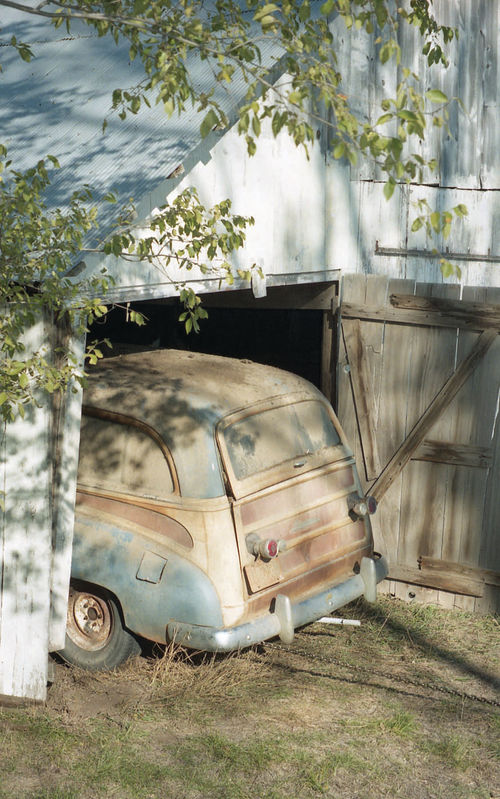

Editor’s note: Last month the author came across a 1950 Pontiac station wagon that had spent 40 years parked in a small farm shed. It was wedged into tight quarters and its rear brakes were locked up. Here’s how he freed the car and took it home:

I proceeded with my backup plan (excuse the pun!) for pulling the nosed-in car out of the farm shed in this manner: I drove a deadman (anchor) stake into the ground 20 feet out from the shed’s doorway. Between it and the car’s left rear spring shackle, I attached a log chain and two 6-foot come-alongs, or manual winches.

As I tightened the chain by cranking the ratchet handles of the come-alongs, the car’s first response was to merely crouch lower in the back, like a lion preparing to jump.

Switching tactics, I jacked up under the car’s differential by placing my floor jack on a short plywood “road.” The heavy station wagon began moving then.

Once the Pontiac’s front end cleared the shed’s door opening, I repositioned the deadman and moved the log chain from its left to its right rear spring shackle.

I wanted to turn the car around to pull it nose-first onto my trailer for the best weight distribution. Accordingly, I jerked the steering wheel to simulate a hard right turn and began winching the car backward in a counterclockwise arc.

Meantime, I continued placing one piece of plywood in front of another to make a road for the floor jack that kept the car’s locked rear brake drums in suspension.

Ultimately, I managed to back and turn the car about 90 degrees so its right side nearly paralleled the end of the shed it had just exited.

Another Day, Another Try

Approaching darkness forced me to quit, however. By the time I’d finish aligning the car with my trailer, I knew it would be too dark to continue working safely during the touchy process of loading it.

This was perhaps just as well. Earlier, when I’d backed my trailer down the slight hill from the farm’s graveled driveway to the shed, I’d felt the engine strain as I pulled forward slightly to better position the trailer.

In fact, I’d nearly spun my truck’s wheels into the soft ground. With a full load on the trailer, I would certainly get stuck. So I left the car, determined to come back at a later date.

By the time the stars aligned so I could shuck off other responsibilities and return to the farm, a full week had passed. During that time, the ground had dried enough to allow me to perform a stunt that, earlier, would have been unthinkable.

Backing down the hill toward the shed, I connected a nylon tow strap between the car’s front frame cross-member and the back of my trailer.

Borrowed from a friend, the trailer— with a sturdy steel frame and a deck of bridge planks—was very heavy.

Several times, even while performing hole shots (revving up the truck engine and throwing in the clutch suddenly), I just barely got rolling above stall speed before the tow strap pulled tight and killed the engine.

On several occasions, I also spun the truck’s tires. Still, I did yank the station wagon ahead a foot or two at each pull.

A Strong Tow Strap Broke

Before pulling the big car, I’d fiddled with the adjusting pins to try to back the brake shoes away from the rear brake drums. My hope was that while pulling the car into position to load, the rusty drums might break free.

At some point while I was winching or yanking on the wagon, its right rear drum did begin turning. It never happened at the left rear wheel, however.

After dragging the car onto a level patch of ground, I resolved to make just one or two more pulls to align it with the most direct route to the driveway.

On the next pull, the tow strap— designed for a 3000-pound steady pull and a 10,000-pound maximum pull— broke. Specifically, the stitching tore away from the hook at one end.

I wasn’t terribly surprised. Besides the locked brake drum, a pair of spongy front tires had handicapped my efforts. The two front tires (used), mounted on the used rims I’d bought, had gone flat. With the small air tank I’d brought along for such an emergency, I’d been able to inflate the tires to just 22 psi apiece—not much for moving a heavy car on soft ground.

Well, I wasn’t about to yank the car with my log chain because of the awful jerk it would bestow upon the old station wagon, not to mention the truck and trailer.

So I repositioned the truck and trailer to align with the stalled Pontiac, dropped the ramps and began winching the car on board.

Slip-Slidin’ Along

After jacking up under the differential, I lowered the frozen left rear wheel onto a piece of bridge planking and placed two identical pieces ahead of the first. All of these I wet down and then coated liberally with liquid car-washing soap.

Surely the tire would slide along the wood now… Well, no, it wouldn’t.

But the plank upon which I lowered the car began skimming along over the green grass, more or less lubricating its own passage. It worked, so I left it alone.

When the locked wheel approached the ramp, I wet and soaped the ramp, turning it into a slippery slide.

With the car safely loaded—it had taken me an hour since lowering the ramps—I faced one final challenge. Dropping the transmission into its ultralow “granny gear,” I gunned the heavily loaded truck, which began creeping ever so slowly up the rise to—Yes, indeed!— finally reach the driveway.

It was a celebratory moment. After all, it had taken me 11 hours over three days (spread over a 3 1/2-week interval), but I’d finally managed to dig out and load a beastly hulk of a car that had spent 40 years slumbering in a rickety farm shed. We were homeward bound!

A Bad Time to Lose Our Headlights

Suddenly, just as I was leaving the farm for an hour-long drive home in the dark, out went my headlights!

I’d been having problems with my dimmer switch, or so I thought. By flashlight, I replaced the “bad” dimmer switch with a spare that I’d bought for such a contingency, and the headlights blazed on.

(As I discovered later, the socket that plugged into the switch was making intermittent contact. I’d fixed the headlights by merely handling the socket, not by replacing the switch.)

The trailer wiring was on the fritz and similarly jury-rigged: I’d attached a pair of battery-powered bicycle taillights in place of the trailer’s dead running lights.

I also had one very exciting moment returning home. While hauling the car in rush-hour highway traffic in east Lincoln, I got caught by surprise when the car ahead of me slowed suddenly.

The truck, heavy with the car and trailer, didn’t want to obey my will to stop, forcing me to stand on the brake pedal—literally—and with both feet.

Such is the nature of manual truck brakes coupled with an old trailer’s feeble-when-new hydraulic brakes. Though I got a bad scare, I did manage to get the truck stopped without smacking into the poor sap ahead of me.

What’s Under All That Grime?

Despite all the hours I’d spent working with and around the car to load it, I was still unsure of its exact condition. Consequently, en route to my rented mini-shop I drove the truck and trailer to a coin-op car wash.

It took 14 minutes’ worth of purchased time with a power wand to strip away the accumulated dust of a 40-year hibernation in a farm shed. My efforts uncovered a pretty medium-blue paint, still in good condition.

Back at my mini-shop, unloading the car provided one additional thrill. A neighbor, Mike, volunteered (under duress) to pull the Pontiac off the trailer.

As usual, I jacked up under the differential with a floor jack, both on the trailer deck and on the ground, after the differential had cleared the back of the trailer.

We attached the car to Mike’s Dodge van with a log chain and pulled. Once the Pontiac’s front wheels started down the ramps, the jack-assisted rear of the car really zipped along; something I didn’t expect to occur on the parking lot’s textured concrete.

I yelled at Mike to pull ahead to avoid getting hit. He did so in the nick of time: the swiftly rolling old car just missed hitting the back of his van.

Because the Pontiac was rolling so easily—perhaps eager to move after years of inaction—it was thereafter a snap to push the car into a parking spot just outside my shop.

The Engine’s Good and Bad News

Although it seems incredible to contemplate, 16 months would pass before I got my first look at the Pontiac’s straight-8 engine.

I have two excuses. One, what little time I had available I spent freeing up the car’s frozen left rear wheel, which I accomplished by towing the car back and forth in the concrete parking lot beside my rented shop.

Two, tired of renting, I had begun constructing a shop building on some farmland I’d bought outside Lincoln, Nebraska. That consumed inordinate amounts of my time. Only after I’d trailered the ’50 Pontiac out to the farm did I attack its rusty hood cable-and-latch problem.

Unable to free up the release cable, I managed to circumvent the hood latch’s supposedly theft-proof shroud by sticking a screwdriver through the grill. Up popped the hood. (Yes, I did exactly what John and I had done back in the shed to jimmy open the car’s glove box!) And what did I find?

I discovered the elemental truth to the saying that when the farmer is away, my, how the mice will play! The restless rodents had chewed away most of the spark plug wires and even the upper radiator hose.

The bad news first: I was unable to turn the engine manually or (when I dropped a battery in the car) with the starter. I’m thereby assuming we have at least light rust inside the engine.

Furthermore, a check of the dipstick revealed contaminated engine oil; its reddish color matched that of old gasoline and, if its acidity does likewise, I can expect to find rust pits inside the oil pan and on every engine part submerged in the stinky old brew.

On the good-news front, the block drain cock was finger-tight, suggesting that John’s grandfather may have drained the cooling system before he stored the car. Seemingly confirming this, my cursory inspection of the block revealed no cracks—or no obvious ones, at least.

The best news of all is that the engine compartment, like the rest of the car, is unmolested.

Revive This Survivor

Because it is so original, complete and solid, this low-mileage classic station wagon is a perfect candidate not for restoring but for reviving and displaying as a survivor.