1940 Dodge VC-5

While a military vehicle typically leads a tough life, the very fact that it’s designed for difficult work sometimes means a survivor goes on for years under unusual circumstances. “My dad found it in a farmer’s field in 1975,” said Ernie Baals, whose 1940 Dodge VC-5 is shown here. “It was a boatyard truck at one of the boatyards on the Delaware River.” Baals’ home in Erial, New Jersey, is about 10 miles from the Delaware, and while that boatyard service is far from the strangest use for an ex-military vehicle, it’s one for which the Dodge is well- suited. Given Dodge’s long history in developing trucks for the armed forces, the featured example is just one among its many designs that could have handled the jockeying of boats.

The Brothers Worked Their Way Up

Dodge Brothers began as a machine shop in 1901 and based on their success in supplying major customers such as Ransom Olds, who bought transmissions, and Henry Ford, who contracted for engines, they were able to expand their business from one that supplied components to the manufacture of complete cars.

Launched late in 1914, the first Dodge Brothers was a four-cylinder touring and was joined in 1915 by a roadster. In 1916 the company earned valuable publicity from the fact that its touring cars were used in the U.S. Army’s Mexican Expedition against Pancho Villa after two attacks in which 37 Americans were killed.

While the expedition was unsuccessful in capturing or killing Villa—years later, Villa was assassinated while driving his own Dodge Brothers—it had effectively provided a means to evaluate the Dodge Brothers and other vehicles in warfare. The experience was not lost on General John J. Pershing, who had commanded the Mexican Expedition and went on to lead the American Expeditionary Force at its 1917 entry into World War I. For Dodge Brothers, the timing again was right since it had just introduced a line of commercial vehicles. The new commercial chassis was a four-cylinder half-ton riding a 114- inch wheelbase that served as the basis for everything from ambulances to light repair trucks.

Dodge Military Ties Continued

Both Dodge brothers died in 1920 and the company was sold to investment bankers in 1925. Walter P. Chrysler bought it in 1928 and at the corporate level, Dodge Brothers finally became Chrysler’s Dodge Division in 1935. That same year, the U.S. Army went back to Dodge for more trucks.

The division had already filled a small order in 1934 and now, most of the 1935 Dodges were again two-wheel-drives. A mix of station wagons, pickups and panels as well as larger cargo-haulers, they were essentially civilian trucks with minimal brightwork, military paint and rudimentary military equipment such as radiator guards and tow hooks. The connection to the regular commercial line was less direct when Baals’ truck was built.

The 1940 VC-1 through VC-6 military Dodges were based on the civilian VC trucks that had appeared as the TCs in 1939. The TC series had marked a big break at Dodge by moving the light trucks’ styling far enough from that of the passenger cars that not even a family resemblance remained. Still, it was the combination of special-purpose equipment and modifications such as four-wheel-drive that turned it into a very different truck. In the case of Baals’ Dodge, all of that resulted in a good match to the boatyard’s needs and by the time it was found rusty and in pieces in the field, the work and the exposure had combined to make it an unlikely candidate for restoration.

This One Needed a Lot of Work

“For the most part,” Baals said, “it was almost all there. But what wasn’t (missing) was rusted beyond belief. It still had the original fenders and you could poke your fingers through them anywhere you wanted. The windshield was folded in half, the cab floor was gone, the gauges were gone, the running boards were worn through. The little nubs on them that you stand on? They were worn through so that you could see through them.”

The explanation for that kind of wear on the running boards is obvious in light of the truck’s post-military life. “Boatyard,” Baals said. “Wet sand; wet dirt. They’d put a hitch on the front of it to drive the boats down into the water.” Rough or not, his father wanted it. He was, Baals explained, not only a World War II veteran, but he also operated a gas station and a used car business and owned more than one collector vehicle.

“Before we got into military,” he recalled, “we had eight Edsels. We had eight Kaisers. I still have one of the Edsels, a ’59 Ranger. Then he just started with the military in the late ’60s, early ’70s because he thought they were neat.”

The plan when he bought the Dodge was to restore it eventually, although the priority was fairly low because he owned other military vehicles in drivable condition and the Dodge needed so

much help. Considering the environment in which it worked along the river plus whatever time it spent in the farmer’s field, the Dodge’s very existence in any condition is surprising.

Some deduction, though, makes a strong case that the body’s extremely poor condition was the reason that the Dodge was no longer useful as even an off-road truck, as it certainly wasn’t a major mechanical problem that banished it. In fact, the mechanical condition when Baals and his father found it might be the biggest surprise of all.

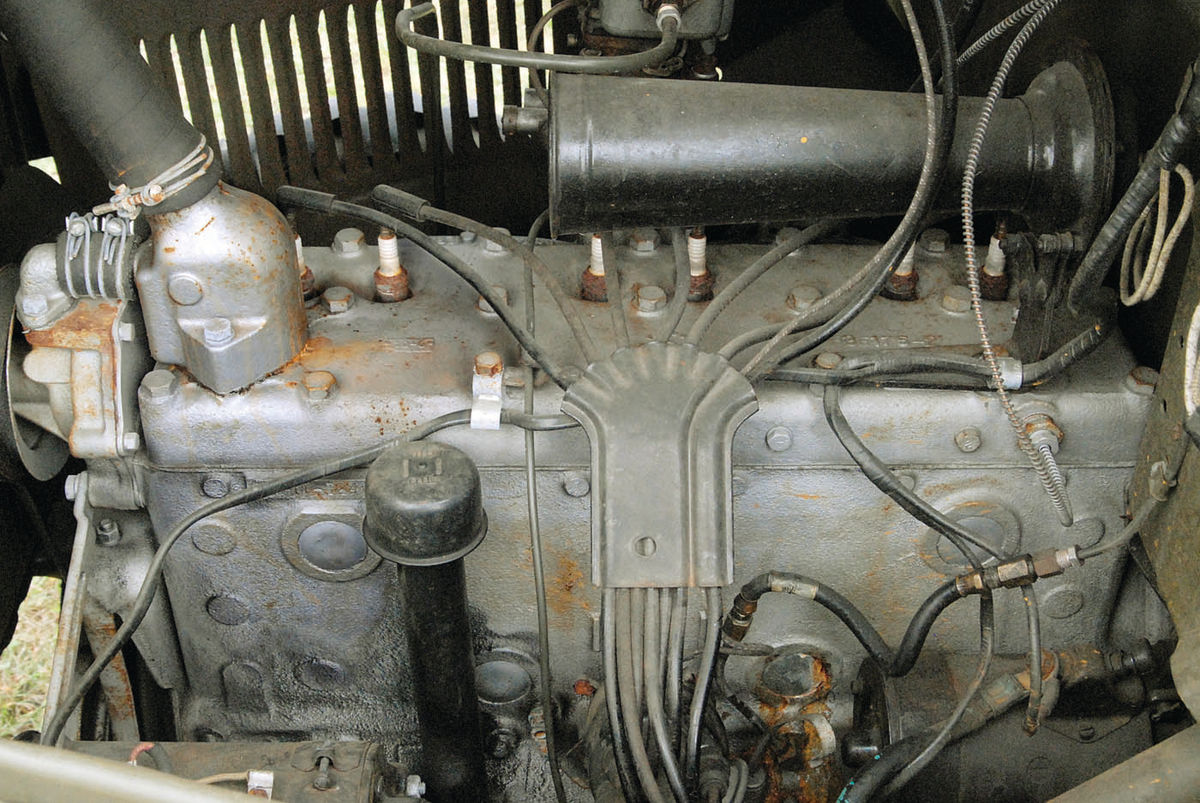

“We did get it running,” he recalled, “and drove it around the yard. That’s the motor that’s in it now. I haven’t rebuilt it. I cleaned it up... Talk about rusty, I had it on the engine stand and I was wire-brushing the oil pan with the drill and I wire-brushed through the oil pan. So I had to change the pan.”

The Truck’s Military Service Brought Special Challenges

It runs well with good oil pressure, he said, and the Mopar faithful might have predicted that since the engine is the everyday Dodge 201-cubic-inch six. In its various displacements over a long life, the Dodge flathead is generally regarded as a strong and dependable engine whose performance is adequate at the very least. That the engine in Baals’ truck was running without much difficulty quickly revealed a problem that later proved to be no problem at all.

“The first few years we had it,” he confessed, “we couldn’t back it up or go into first gear. We thought the transmission was bad, (but) there’s a lock-out on the transmission itself so that you cannot engage it in first gear or reverse unless you’re in four-wheel-drive and we had no idea of that until we found a manual, finally. We just figured that the tranny was bad and we parked it so it didn’t have to back up.”

Not recognizing the odd quirk without a manual points to the special types of challenges any prospective military- vehicle restorer could face, as even a truck that appears to be close to a standard commercial model is likely to have significant differences that— like the Dodge’s lock-out—might not be immediately apparent. And if it’s an uncommon military vehicle, some of those challenges could be greater.

“I don’t think he knew how rare it was,” Baals said, “until we got it home and started researching it. They made a little under 1800. There are eight or nine left that I know of with the original open cabs on them and probably another 30 or so that have been re-cabbed with civilian cabs.

“They were worthless (for civilian use) as an open-cab. Same with the command car. I’ve found so many that were command cars and are flatbeds now. Just throw the body away and a farmer can use it. “As far as I know, mine is the only one with the correct sheet metal, correct transmission, correct transfer case. We got lucky on that.” The command car is a VC-1, while Baals’ VC-5 is a weapons carrier or open-cab pickup. The other versions are the VC-2 command radio truck, VC-3 and VC-4 closed-cab pickups and VC-6 carryall. Bodies vary, but they share the same drivelines.

Among its other problems, Baals’ truck had the wrong front axle when his father found it and the correct axle is unique. He guessed that it was prone to problems, as an early-wartime rebuild program replaced VCs’ front axles with those designed for later Dodges.

“The front end is the weakest link in the whole thing,” he said. “That was the hardest thing to find. We had a (Military Vehicle Preservation Association) member who just had a pile of parts from one he scrapped. There were a couple of five-gallon buckets of parts and an axle housing. We bought another closed-cab, really bad, that had the front axle housing and guts and then (another collector) sold us a set of front and rear axles that were complete. Between all of that, I got enough parts to build one front axle.”

Surprise! Rarity Can Be a Problem

Even more than the roughly 1800 built and what Baals had to do to come up with a complete front axle, the experience of a good friend who completed much of the bodywork tells the story of the Dodge’s rarity.

“He restores muscle cars as a hobby,” Baals said, “That includes Super Bees, so he likes Dodge. When he first found out about it, he evidently spent a day calling people to find some information about it and everybody he called gave him my number to call. He finally called me and said ‘do you know how rare these things are? Everybody I call says to call you for information.’”

That realization of rarity grew as the restoration really got underway in 2010 and the chassis was soon found to have problems beyond an incorrect front axle. Rust had destroyed three crossmembers and indirectly, that revealed some of the similarities and differences between his truck and the civilian edition. The replacement crossmembers came from a civilian 1940 pickup that lacked a drivetrain, but was nearly rust-free and thus an excellent donor truck. Excellent, but not perfect.

“That donated the running boards, the fenders, the bed, the cab floor,” Baals

said. “But they all had to be modified. The wheel openings in the fenders are different. We had to open up the fenders’ wheel openings. We made templates from the remains of the originals, drew it on the outside of the fender, added a half- inch to roll it back under, cut it, tacked an eight-inch rod behind it and then just used water pump pliers to fold over the metal all the way around the wire bead on all four fenders.

“Actually, it was a lot easier than I thought it would be rolling the metal. I thought I’d have to heat and dolly and use special tools. I just worked my way around with water pump pliers and a little bit with a metal dolly and it straightened out.”

There Were Many Sheet Metal Modifications

Creating the spare-tire well in the passenger-side rear fender meant further work that began with sheet metal of roughly the right configuration that was then worked into the proper shape and welded into place. The running boards, too, demanded modification, as Baals realized during a test-assembly that those on a civilian Dodge are slightly shorter than the ones on his truck. The parts truck’s cab floor also had a minor difference.

“We cut the cab apart, took the cab floor out of the closed cab and grafted it onto the cowling,” he explained, “but they originally must have used the floor out of a panel. On the panel trucks under the passenger seat, there’s a lid to a little tool compartment that hangs down underneath. These cabs have that lid there, but there’s no tool compartment because the crossmember that holds the transfer case up is there. All I can figure is that because it’s a panel floor, I guess it’s different than a closed-cab floor. I finally found a couple of pictures from the archives where you could see under the seat and ‘son of a gun, there’s a lid there.’”

The feature truck’s cab floor still had one question left to answer, as he had to determine how the seats were mounted to the riser so that they would fold.

“We had the remains of the original wood bases for the seats,” he recalled, “and the remains of a hinge. Nobody’s ever had an original seat hinge on one and so we figured it out and that’s about it. The seats I’m guessing are right from lining up stuff, but the other guys I’ve talked to who have them all said the same thing. ‘You’re the first one who did it, we’ll copy yours.’”

The A-pillars are the same as those on a civilian cowl-chassis, he said, as is the dashboard. The grille is civilian, too, but that’s less help than might be expected. As mentioned above, Dodge trucks were new for 1939, but tinkering with the brightwork on the grilles made 1940 a one-year-only design and since many commercial vehicles of the immediate prewar period were driven to death by the time the fighting ended, finding a 1940 Dodge with a good grille is likely to require serious hunting. The good news, though, is that under the brightwork is sheet metal that will interchange among light-duty Dodges through the series’ end in 1947. Similarly, the boxes can be swapped with just minor modifications.

“They’re the same stampings for the ’39 to ’47 half-ton pickups, all the (pickup- based) VCs and all the half-ton WCs,” Baals said. “The actual sides are the same stamping; you just have to add the center bow brackets because the civilian trucks didn’t have them and then weld up all the holes in the fenders and re-drill all the holes for the new fenders because they’re in different locations.”

One Especially Difficult Parts Search

One component that’s identical to its civilian counterpart and found on more than just pickups actually proved to be a headache. “About the hardest thing to get,” Baals said, “was the taillights. They have a curved ‘Dodge’ on the top. Forty was the only year they did that. The hardest thing to find was two of them.”

A missing windshield assembly is even less easily dealt with as it can be replaced only with one from another VC- 5. Baals said that it lacks reinforcements and he believes it’s not strong enough to support the canvas top even though he’s confident that it’s the correct windshield for his truck. It’s one of five made by another collector who owns several VCs slated for restoration and finding it was a lucky break.

The other models are built on either windshield-cowl chasses, closed-cab pickup chasses or panel chasses, but the VC-5 is based on the flat-face-cowl chassis that in civilian form would have been used by a builder supplying bodies such as buses or deliveries. On the VC-5, though, the flat-face cowl has no greenhouse with which to meet and so sheet metal is simply folded over at the top of the cowl leaving a space under the windshield.

Replacement parts such as the windshield and sheet metal coupled with the modifications necessary to some of the civilian components led to what Baals said was among the most time-consuming phases of the project.

“The longest time spent other than just cleaning the sheet metal was trying to line up the sheet metal on the front end,” he explained. “I’m still not happy with how that lines up. I’ve seen un-restoreds that are better, but I don’t know whether the frame’s twisted. I’ve never taken it to a frame-straightener or anyone like that. Even if I did find out, am I brave enough to put it on a machine and start twisting it or do I just leave it?

“I guess the next hardest thing was assembling the headlights because they’re reflector-and-bulb. I’ve done it and I can’t tell you how they stay together. The reflector is locked in with springs and clips—springs in front—you cock the headlight lens, push it in, twist and slide it down. Then there’s this little L-bracket and when you screw the bottom, it comes up and touches the glass. That’s it. I keep looking at it and saying ‘what keeps that lens in?’ Unless the opening is just eccentric enough and not round.”

Keeping the lens in doesn’t take much when the truck is parked, but it does seem that any bump could be a problem once the truck is underway. “I’ve thought that,” Baals said, “many times.”

Be Sure to Hold On Tight

He’s not really testing the possibility with the headlights because since its completion in 2011, he hasn’t driven the Dodge very much. He has, however, had it out enough to know that it gives no indication that its frame is anything less than straight and that it’s adequately fast. He explained that his son drove it to a show several miles from his home while he and others followed with additional vehicles.

“He took off,” Baals said, “and none of us could keep up with him. The first thing he said when he got there was ‘damn, that thing is peppy.’ He said he hit 50 quite comfortably going down the road with it. He said it was a busy 50, especially with the steering.

“It’s kind of squirrelly. They must not have understood caster and camber in the front end. They don’t correct when you let go of the steering wheel. It’s kind of like driving a lawn mower; you let go of the wheel and whatever way you let go, it’s going in that direction. You’ll spend a lot of time twisting.” You’ll also spend a lot of time holding on.

“You sit up high and there are no safety straps,” Baals said. “The jeep has the safety straps; there are none in this model. It’s not bad for the driver because he has the steering wheel to hold onto, but the passenger? You’re higher than anything else you sit in and there’s nothing.”

It May Be Uncommon... But It’s Recognized

Most likely, the sensation is worse than the reality—much as the headlight lenses manage to stay in place—but confirming that will take some time given the truck’s infrequent use. The short trips it’s made, though, have produced some interesting reactions from those who see it and Baals spoke of its participation in the AACA’s Hershey Fall Meet beginning with its entry and exit on the long road into the show. “It was funny driving in and driving out,” Baals said, “because you drive for blocks and I heard a couple of times ‘wow! A VC!’ ‘Wow! A VC!’”

That was neither a fluke nor some bizarre coincidence where a few spectators who could identify a VC happened to see it. Once on the field, the Dodge was at least as well received. “A lot of people knew what it was and had never seen one,” Baals said. “A couple of people had the remains. ‘Where did you find it?’ ‘How long have you had it?’ ‘Where did you get the parts?’” And some who saw it reacted with what amounted to forehead-slaps straight out of cartoons.

“Yeah,” Baals laughed, “there were a couple people like that.”