The Case of the “Imprisoned” Pontiac, Pt. 1

After It Had Spent 40 Years In a Small, Junk-Filled Shed With a Dirt Floor, Removing the Station Wagon Would Not Be An Easy Task. Still, He Was Determined…

In late 2002 a friend of mine, John, began circulating a photocopied sheet listing 15 older cars scattered about his grandparents’ farm near Syracuse, Nebraska. Would I like to see them in person?

Well, sure!

John’s grandfather had died some 14 years previously; his grandmother had died only recently. It was, consequently, time to clean up the farm and sell it.

John laid claim to a ’64 Imperial that, fortunately, his grandfather had parked inside. The rest of the vehicles scattered about the farm were up for grabs.

It turns out John’s grandfather had a propensity to park a disabled car outside, lined up in a grove of trees, whenever it was time to buy another car— typically another used one. I bypassed various 1950s Chrysler products as too weathered, something I now regret as at least two of them were equipped with early Hemi engines.

But—Aha!—a certain General Motors car, in much better condition than the others for having been parked in a shed, had unexpectedly captured my fancy.

A Hidden “Woodie”

The massive 1950 Pontiac station wagon, powered by a flathead straight-8 engine, was an “internal woodie.” That is, it sported wooden door panels and other interior trim while merely using paintedon woodgraining to create the illusion of wooden exterior panels. (For the story of two more such “woodies” see page 26.)

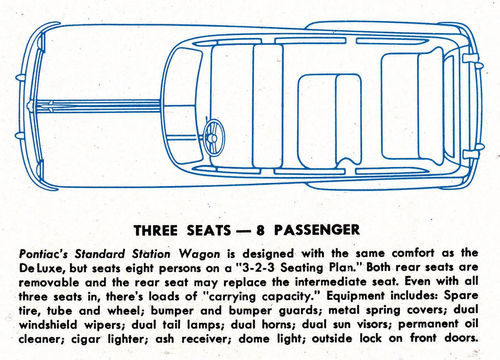

The Pontiac was an 8-passenger standard model—it had a vinyl instead of the deluxe model’s leather interior, for one thing—that used a “3-2-3” seating layout. In simpler terms, it had two bench seats behind the front seat, allowing it to carry 8 people versus the deluxe model’s 6 people.

Sensing my interest in the old wagon, John drove me over to visit an uncle, who, as a child, had ridden in the car on a family vacation to Colorado in the early 1950s.

His uncle, also named John, recalled that in 1962 when the car’s Hydra-Matic transmission quit shifting into reverse, his father (grandfather to my friend) drove the wagon into a shed on the farm and simply left it there.

Seems he’d been too busy farming to attempt his own repairs and was reluctant to spend much money on a 12-year-old car.

The Pontiac had been sitting, forlorn and forgotten, in the shed for upwards of 40 years. (The 1963 license plate stickers suggest that Uncle John’s memory was off by a year.)

From Uncle John and other family members, I learned that the storied wagon once hauled a stud ram, purchased at the Nebraska State Fair, down Lincoln’s busy O Street and back to the farm at Syracuse.

As the kids grew up and family vacations tapered off, the car saw less and less use— very little, in fact, after 1958.

A Surprisingly Nice Exterior

Just four blemishes marred the station wagon’s otherwise pristine body: 1) a puncture wound in the center of its tailgate; 2) the left front fender’s bowedout lower lip, caused by the car’s settling into the shed’s dirt floor; 3) a dent low on the left quarter panel near the rear bumper; 4) and a bent front-bumper tip.

Inside, despite a distinct mousy odor, the car’s vinyl upholstery, floor mats, dashboard and the like were as nice as you’d expect from a car driven just 51,918 miles. A virtual time machine, the car had been abandoned in the prime of its life, the key still in the ignition switch.

The Recovery Became an Ordeal

After buying the old wagon, my struggle to remove and load it turned into the longest car-recovery campaign of my life for manifold reasons (none actually involving a manifold): 1) the shed was not only narrow and low but one of its twin outward-swinging doors was stuck; 2) mountains of heavy junk limited access; 3) the car’s wheels and tires were missing; and 4) both of its rear brake drums, which had settled into the dirt floor, were frozen tight.

A day after viewing and buying the Pontiac, I returned with John to inspect several more outbuildings on the farm. To our disappointment, none harbored old cars. Thus at about 11 a.m. John pitched in to help me begin digging out the Pontiac on what would become Day 1 of a 3-day ordeal.

As we’d learned a day earlier, the right half of the shed’s twin swing-out doors opened easily; the left half was stuck, its lower edge pressed into the hard ground. I’d brought a shovel and was ready to excavate.

But at John’s suggestion, rather than dig out the bottom of the left-hand door, we pried out the long and heavy nails that secured its two hinges to the door frame. We then half-lifted, half-dragged the door aside.

Bared to the Light

With both halves of the swinging doors now open, we could see inside for the first time without using flashlights. Coated with dust, the squared-off rear end of the station wagon sat just inches behind the shed doors.

Like a meandering river, the leaky old shed had gradually filled with silt. Over the decades, several inches of soft, powdery dirt had accumulated on the shed floor. Similarly but more noticeably, junk had drifted in to accumulate in towering piles next to the old Pontiac: easy chairs, engines, window panes, farm equipment and on and on. Like the Pontiac, it was all stashed in the shed for “some day.”

The concrete blocks that John’s grandfather (I presume) had placed beneath the brake drums in the early 1960s were still in place, if barely.

Evidently, the car had settled forward over time, and its rear blocks angled forward like a pair of sinking ocean liners, leaving the differential half-in, halfout of the dirt.

Although someone had shoved boards under the back of the car to prevent it from happening, the rear universal joint and brake drums had also become partly buried in the dirt. The boards did save the gas tank by keeping it from sitting directly on the ground.

Not surprisingly, the Pontiac’s rear drums had rusted up and refused to turn. I got better news at the car’s front end, which had remained above the shed floor: both brake drums still turned easily by hand.

Digging Out the Derelict

Here my shovel came in handy as I set about raising the four corners of the 3800-pound station wagon, starting at its most-accessible right rear corner.

I began by digging out as much loose dirt as possible. Next, I placed a piece of plywood on the ground to support my floor jack, which I slid under the car. Finally, I raised the corner far enough to block it up

I performed the same tasks, though with increasing difficulty, at the Pontiac’s other three corners.

The problem was the shed, so lowslung that I had to watch carefully to avoid bumping my head. It was, essentially, an early pole barn: a wooden framework with corrugated sheet metal nailed on to form the side walls and roof. Wooden siding covered the front end wall. As viewed from the front, the entire building was leaning lazily to the right.

“We’d better hurry,” I joked with John at one point. “There’s no telling how much time we have before the whole thing caves in on us.”

After raising the car’s right front corner, I ran into trouble while blocking up both left-side corners. For one thing, because of a low rafter just ahead of the car, I found it hard to wield my shovel to dig out under the front bumper.

Dodging Sharp Nails

What’s more, the driver’s side of the car cleared the shed wall by perhaps 16 to 20 inches. While jostling around in this tight space, I had to dodge dozens of sharp points from the nails that attached the steel siding.

A day earlier, we’d been unable to open the glove box. Today, we met with similar results, even after trying to open the glove box lock using two keys folded into the ignition key’s leather fob.

We got in, ultimately, by using John’s pocket knife to reach past the top edge of the glove box door and thereby depress and release the door latch, all without harming the door or mechanism. Sure enough, we found the car’s original owner’s manual inside…definitely showing its age.

Though tattered and mouse-nibbled, the manual told me the correct tire size— 7.10-15 6-ply, which equals a modern 225/70R15 tire—I would need for getting the wagon rolling again.

The Engine Remained Hidden From Me

Although this was my second visit to the car, I’d still been unable to open the hood using the remote-control cable on the lower left side of the dash. I was eager to view the straight-8 engine of which the car’s fender tags boasted.

It’s possible that I didn’t pull hard enough on the hood-release cable: I wanted to avoid breaking either the cable or its knob, after all, knowing that a 40-year buildup of rust had undoubtedly frozen the cable or latch— possibly both.

It appeared that reaching through the grille bars to jimmy the hood latch— similar to the way we’d opened the glove box door—wasn’t in the cards, either. As an anti-theft measure, Pontiac engineers had placed a sheet-metal shield around the latching mechanism. I did spray some penetrating oil around the shield, however, hoping that it would somehow drip inside.

Although the hood remained locked at the end of Day 1’s four-hour work session, we did make some progress. For one thing, we’d succeeded in opening a stuck shed door and digging out and blocking up the heavy car in cramped quarters. Best of all, we’d found two of the car’s original rims and tires elsewhere in the shed.

Two Weeks Roll By...

I devoted much of the next day to seeking two more rims. This meant driving an hour south of Lincoln to Watt’s Salvage & Repair near Wymore, Nebraska, where I discovered four or five 1949-50 Pontiac parts cars, all sedans. From them I removed two rims ($20 apiece) and a full set of lug nuts.

Ultimately, a local service station let me scrounge four old but decent 15-inch tires from its scrap pile, which a Lincoln salvage yard with a tire machine mounted for a few dollars.

By this time, many days had passed, due in part to conflicting projects and troubles with my truck and a borrowed trailer that sank in the mud at my storage area. Wet weather further delayed me.

Finally, more than two weeks after John and I had previously visited his grandparents’ farm, I returned alone to resume extricating the Pontiac—Day 2 of the 3-day expedition.

My plan upon arriving at 11:30 a.m. on a Friday in early November was fairly simple—in theory. First, I wanted to clean up enough of the car’s 20 very rusty wheel studs to mount the wheels and tires I’d brought with me. Next I would lower the blocked-up car and begin winching it out of the shed.

In fact, my day proceeded according to plan except that everything took much, much longer than I’d expected it to.

Where’s the Wire Brush?

I was partly to blame for this delay. When I’d heaped tools and supplies in my truck that morning, I’d forgotten one important item: a wire brush. I therefore had to clean the lug studs with the small terminal brush on the battery-post cleaning tool in my toolbox.

But then I was merely planning to load the car on a trailer—not drive it. So I opted to clean just two studs per wheel. This still meant brushing each stud, soaking it with WD-40, running a lug nut on and off to further clean the threads and then giving the stud another blast of penetrating oil to remove any leftover rusty residue.

With the wheels mounted, I centered my floor jack under the frame to raise first the car’s entire left side and then its entire right side. This allowed me to remove two concrete blocks at once versus one block at a time, which was all I could have achieved by jacking up each of the car’s four corners in turn.

To smooth the car’s eventual exit, I shoveled the large piles of dirt from behind each wheel. Depressions remained from where the four old concrete blocks had sat for 40 years, however. To keep the new tires from dropping into them, I lined these holes with chunks of scrap 2-by-4 lumber.

I would have trouble, I knew, pulling a car with locked rear drums backward out of the shed. Though tempted to hunt up a neighbor with a tractor, I ultimately discarded the idea: I didn’t want an impatient, careless helper to damage my prize.

On the other hand, the wet sod would thwart any attempt to pull the car out with my 2-wheel-drive pickup. Times like this, I knew, called for creative thinking.

Next time, an attempt will be made to extract the 1950 Pontiac station wagon by constructing two roads—one of plywood, the other of bridge planks.