1959 STUDEBAKER SILVER HAWK

This Finned Studebaker Already Was an Orphan When His Family Bought It. But It Came Into a Long-Term Home With Folks Who are Fans of the Breed.

DAVE PRISLUPSKY’S STUDEBAKER was 10 years old when his mother bought it and its life began taking a series of turns for the better, even if there was one lengthy detour along the way.

“My mom gave it to me when I turned 16,” Prislupsky said. “She’d bought it used from a fellow who’d bought it wrecked and fixed it so that it was driveable. He was a car enthusiast. He’d buy a car that might have been in trouble, fix it up a little bit and sell it.

“She just liked the looks of it.”

Someone else who bought a 1959 Silver Hawk at that point might have been thinking in terms of cheap used transportation; after all, the fact that Studebaker was out of the automobile business was something very fresh in many people’s minds in 1969. Studebaker had ended operations at its South Bend, Indiana, complex in December of 1963, but continued production at its plant in Hamilton, Ontario, into 1966 before everything came to a stop.

It Was Wagons, Not Cars, In 1852

Existence for Studebaker and its fellow Independents had rarely been easy, of course, competing as they did with the Big Three’s resources and economies of scale. Having been around since 1852 and gotten a solid start in wagon-building, Studebaker actually predated the auto industry, which it finally entered in 1902. An agreement to market E-M-Fs led to its acquisition by 1912 and helped Studebaker to become a force even as other, smaller Independents were vanishing over the next two decades or so. Thanks to some product missteps and a failure to recognize the magnitude of what would become known as the Great Depression, Studebaker almost went with them and it found itself operating in bankruptcy in 1933.

It had owned Pierce-Arrow since 1928 and now sold that high-end builder. Studebaker emerged from its financial difficulties in 1934 and then began the hard work of turning itself around. Sales gradually recovered and as World War II approached, the company was healthy enough to begin fulfilling military orders including its 6x4 and 6x6 US6 trucks and its M28 and M29 Weasel tracked carriers.

Coming Back With a One and a Two…

At the war’s end in 1945, Studebaker was one of a handful of remaining Independents and in a spectacular example of simultaneously seizing the moment and taking a risk, it had a plan.

First, the company did about what the competition would do by reintroducing one of its 1942 models, making some simple changes and calling it a 1946, but production ran for just a few months.

The second step, though, was the important one as Studebaker launched its 1947 line in early 1946 and broke almost completely from the past. The new cars looked low, clean and modern with not a trace of the prewar boxiness. Rear fenders were still separate, but seemed to be more of a suggestion, while the panels ahead of them were smooth and nicely integrated. The new Studebaker stood out among its contemporaries and no one had anything like the C-body, a coupe later known as the Starlight. Its rear window not only wrapped around, but extended all the way to the B pillars.

For 1950 the company updated the body with a front end whose “bullet nose” nickname was perfectly accurate. The almost-flat grille with its horizontal theme was gone, replaced by a ring at the center of jutting sheet metal, with a less-unconventional mesh opening below at each side. The fenders also jutted forward so that when viewed from above, the effect was that of an upper-case “M.” It was a futuristic design in line with the thinking of the day, but the future grows old quickly and Studebaker exercised some restraint for 1952 by giving it a basic split grille and slight shovelnose.

Those last updates were made to ease the transition to the completely new 1953 Studebaker, a car that would prove exceedingly important years later in ways nobody could have foreseen. The look now was one of elegance with long lines, minimal stamping on smooth sides, a simple grille split by the hood’s center and on hardtop and pillared coupes, the long-hood-short-deck proportions that would later be popularized by the Mustang.

Studebaker had the good sense to keep the changes small for 1954, but still, things were not going well. For reasons ranging from delays in getting the 1953 models off the ground to being caught in the crossfire between General Motors and Ford, sales were less than expected.

Two- and four-door sedans were updated heavily for 1956 to the point that many who saw them probably believed they were looking at entirely new cars when they were really seeing the body introduced for 1953 with revised front and rear clips. Station wagons received the same nose and the addition of small rear fins similar to those that had appeared on the sedans.

The Hawks Swoop In

While Studebaker had reason to be pleased with its family cars, it wouldn’t have been Studebaker if it had stopped there. The coupe and hardtop had been left out of the 1956 redesign and instead received their own touches to become the Hawks.

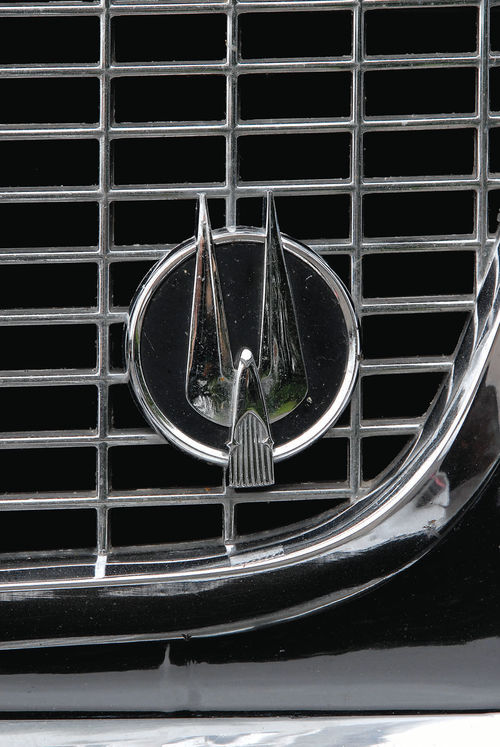

Very clearly using the 1953 body, they now carried an almost-upright mesh grille centered in the hood and the original low side grilles that had disappeared in 1955 were back. At rear, a reshaped deck lid was the big new feature, but even that wasn’t everything.

Just as Mustangs and Camaros would one day be available in any form from docile to outrageous, Studebaker chose to attract potential Hawk-buyers with possibilities. The basic Flight Hawk relied on a 185.6-cubic-inch, 101-horsepower flathead six while the Power Hawk carried the 259 V-8 with 170 horsepower. The Sky Hawk received a 289-cubic-inch version of the V-8 and its 190 horsepower was likely enough for most drivers, but Studebaker took no chances and went one step further with the Golden Hawk. Its high-end trim and performance image backed up Studebaker’s advertising claim that it was the “king of the highway.” To further bolster that statement, the Golden Hawk borrowed a 352-cubic-inch V-8 from its Packard sibling. The result was 275 horsepower and what should have been a great halo car for the time.

But it didn’t work out quite that way. The Golden Hawk was in Buick territory at just over $3000 — expensive, but not unaffordable — and the Flight Hawk was priced just under $2000 in entry-level Chevy territory. Those who wanted Golden Hawks and lacked the money might have been expected to choose one of the lesser models and some surely did, but the numbers for all Hawks combined weren’t high.

Studebaker had to have been dismayed, given that it had thought them out, advertised them as “family sports cars” and seemingly understood the drivers who would be attracted to them. After all, its advertising asked “breathes there a man who hasn’t pictured himself behind the wheel of a sports car, putting it through its fanciest paces? Yet, despite our dreams, most of us must consider the whole family when buying a car. Well, Studebaker’s got the answer.”

Its answer, of course, was “the first full line of family sports cars,” but the line was revamped for 1957. Only the Golden Hawk was carried over and since the corporate decision to drop full-size Packards meant the 352 was no longer available, it was replaced by a supercharged 275-horsepower 289.

Joining the Golden Hawk now was the Silver Hawk with the Golden Hawk’s now-larger fins and either the Flight Hawk’s six or a 225-horsepower 289. The supercharger was mildly exotic at the time, but it didn’t save the Golden Hawk and for 1959 that left only the Silver Hawk, now with a 259. The model year also brought the Lark, a compact still based on what was already a six year-old design and one that ensured that the 1953 Studebaker in effect would live on until the end. The Hawks continued almost as long, with 1960 and 1961 editions dropping the “Silver” from their name and 1962 bringing the final installment, the Gran Turismo Hawk with its new formal roofline and no fins.

Orphan Status Wasn’t a Problem

Unlike the Lark-based compacts, the Hawk didn’t move to Ontario and thus had a head start on becoming an orphan.

Any negative connotations attached to an orphan car are virtually gone today so that someone driving a Mercury, Pontiac or a Plymouth doesn’t feel awkward or embarrassed, but that was still a consideration 45 years ago. The smart ones knew that and used it to their advantage. Among them was Prislupsky’s mother, who wasn’t looking for a car, but...

“At the time,” Prislupsky recalled, “she was driving a perfectly good ’64 Fairlane. She’d had a Studebaker previously and she’d always liked the looks of a Hawk, but by then, they had pretty much disappeared anyway. She saw this one and that was it. She had to have it.”

The Hawk was on a used car lot in Binghamton, New York, not far from Prislupsky’s home in Kirkwood. The progression from seeing it to owning it was neither quick nor smooth, beginning with its being sold between the time his mother stopped to look at it and the time she returned with the cash. The new owner then had an accident with it, but continued to drive it and Prislupsky’s mother soon spotted it.

“Then when he put a ‘for sale’ sign in the window,” her son recalled, “she had my brother and me get out of the car and knock door-to-door until we found who owned it. That’s one of the things (the previous owner) told my wife. ‘This kid walked up to me and said ‘hey, Mister, do you want to sell that car?’”

He did and Prislupsky said primer on the body wasn’t a problem, but a main bearing was knocking and that required attention. A factory short block in the crate cost $125, unassembled.

“All of the pieces were tagged,” Prislupsky said, “and at the age of 15, I put it together and I put it in this car. That’s what’s in it. This is that engine.”

His mother drove it until about 1972, when she gave it to him.

“She knew I liked Studebakers,” he said. “Actually, what happened was that I bought a Studebaker Lark for $15 because I had no money and she was afraid I was going to kill myself in it, so she gave me this car.”

With the fresh engine it ran well, but Hawks aren’t known for resisting rust and in 1973 he installed the first of two replacement quarter panels. A friend tactfully suggested that if he wanted to restore one, starting with a better example might be wise, but Prislupsky bought a winter car so that the Studebaker would be spared exposure to road salt and oddly enough, it proved to be the wrong move.

“Then that became my interest,” he said, “so I didn’t really look at (the Hawk) again until about ’82 or ’83, at which point my wife and I had set a date to get married in ’84. I thought ‘boy, it’d be neat to have that for a lead car in the wedding’ and that’s when I started working on it again.”

Outdoor Storage Aggravated the Situation

The first problem was the car wasn’t in the garage, but behind it, where it had been parked long enough to have deteriorated badly. A hole in the floor had provided access for cats who treated it as their community sunroom, and Prislupsky said that he began to think that he should have followed his friend’s advice, found a better one and used the feature car for parts. After dismissing that thought, the work got underway as he dealt with the floor, replaced the other quarter panel, installed two front fenders and addressed all of the lesser problems.

“Lots of time sanding and scraping,” he said, “it probably took about a year and a half. Eventually, it came around. I had worked with a buddy at a body shop a few years previous and he was painting cars on the side. I prepped it, but I really didn’t have a good place to shoot it and I knew how well he painted, so I wanted him to do it and that’s how it went. I think I finally buffed it and reassembled it heading out of the winter of ’84, toward spring. It made it for the wedding.”

Don’t Do As I Did…

Although he hadn’t acted on his friend’s suggestion to seek out a better example, it was the first recommendation he offered to anyone considering a Hawk as a restoration project.

“Just like any old car,” Prislupsky said, “if you can get one that has less rust, that’d be the one to get. The mechanical stuff is pretty straightforward and easy to come by, but to find a good solid body would be the tough part.”

Rusted fenders and doors are common, he said, as are problems in the rockers and door bottoms, but some of that isn’t necessarily the nightmare it might seem.

“The fenders bolt on and the rockers are easy to put on,” he explained. “Major rust? I would worry about how far into the floor it was rotted away, the structural integrity of the pillars. The same with the trunk. There are people who reproduce that stuff, but you’re always better off buying a solid car. I wouldn’t be afraid of a rusty fender, but I would be afraid of a floor rusted to the point where the door drops when you open it.”

Something else that shouldn’t instill fear is the Hawk’s stainless steel trim. Unlike its plated trim that’s going to be costly to restore, the stainless might be discolored, scratched or dented and still be repairable with straightening and polishing. The skills can be learned with a lot of practice and the necessary tools are affordable. But if trim is missing, that’s another matter. Even a solid and relatively nice car is likely to be short a few pieces of trim or other parts and it’s at about that point that a first-time Studebaker-owner realizes that he made a really good choice.

“Because of the Studebaker Drivers Club,” Prislupsky said, “somebody always has the part that you need. The most recent thing I had to do to this car was put a headliner in it and some of the retainers weren’t even available as new ones through vendors, so I called a fellow down in Texas. He went through his parts cars and found me some. You can find stuff; because ofthe Studebaker Drivers Club, you can find stuff (studebakerdriversclub.com). None of the trim is impossible to get. Some ofit’s pricey, but it’s available. They reproduce some of it, but if you can get original, that’s always better.”

1959 Silver Hawk

GENERAL

Front-engine, rear-drive two-door post

ENGINE

Type Overhead-valve V-8

Displacement 259 cu. in.

Bore x stroke 3.562 in. x 2.25 in.

Compression ratio (:1) 8.8

Power 180 hp @ 4500 rpm

Torque 260 lb.-ft. @ 2800 rpm

DRIVETRAIN

Transmission 3-speed automatic

BRAKES

Brakes Drum/drum

MEASUREMENTS

Wheelbase 120.5 in.

Length 204 in.

Weight 3140 lb.

Going for a Quiet Drive

He did get an original dash in a parts car he bought and he used that to replace the damaged one in the feature car. The swap included the proper radio, whose Conelrad triangles at 640 and 1240 kilocycles caught my eye when we took the Hawk for a ride.

Much more important than Cold War relics, though, was the almost complete lack of body noises. Serious bumps in the road produced barely noticeable suspension squeaks, as did passing over a railroad crossing that was less than perfect. Prislupsky said that the buzzing — he heard it, I didn’t — was coming from the air cleaner housing, but the car was quiet enough that we both could hear a slight ticking from the tach.

A two-door post would almost always be less noisy than a hardtop, but beyond that, it shouldn’t be much different unless the driver pushed the car to the extreme. I didn’t, because it’s not my car and because it’s more interesting to experience it in real-world situations. I’ve driven Hawks before and I like them, so I mostly knew what to expect. As I remembered, the Borg-Warner automatic lets you know it’s shifting with an action that’s crisp rather than a bang.

“You know it happened,” Prislupsky agreed, “but it’s not a big event.”

That’s really in keeping with the Hawk’s character. Its steering is surprisingly tight and precise for a car of its time, but it doesn’t require a lot of effort, and while the driving position is comfortable, it’s doubtful that anyone would mistake it for that of a modern vehicle. The small rearview mirror and the lack of outside mirrors requires adjustment, but overall, the Hawk would be a great car for an all-day run and Prislupsky said it’s ready. He’s done roundtrips of several hundred miles and said longer ones would be no problem even on a modern highway.

“It’s actually happier moving at a better speed than idling around town,” he explained. “Idling around town, it’ll get warm, but going down the road would be effortless.”

He knows it well, since he completed its restoration 30 years ago and owned it roughly a decade earlier. His friends at the time he got it, he said, probably recognized even before he did that he’d have the Studebaker forever.

“I remember that at one class reunion,” Prislupsky said, “they wanted everybody to make a statement. I said ‘I finished the Hawk.’ Everybody understood that.”

Editor’s note: The Silver Hawk was another good fit for the 25th or Silver Anniversary year for Auto Restorer.