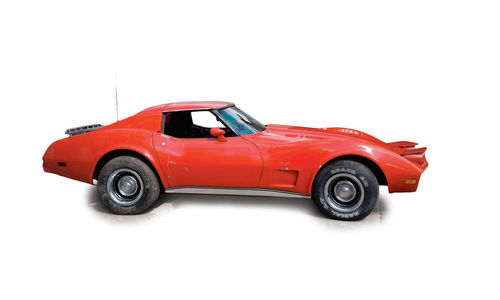

Heidi’s Orange Corvette

Actually, It’s Not Heidi’s Anymore. She Dropped Out and a New Owner Has Enthusiastically Taken Over the Project.

When we found out that our young mechanic, Heidi Schaffer, had totally given up on her ’77 Corvette project, we figured this series of articles was over. But thanks to a young man named Ryan Phillips, we can tell you about an exciting new phase that the Corvette project has entered and what it will be going through in the not-too-distant future.

We won’t dwell on the negative aspects of giving up on a project. We all know that it’s easier to take a car apart than it is to fix the pieces up and put it back together. Heidi was 25 years old and exploring different life options. She decided to switch her focus from working as an auto mechanic to undertaking a new job with Miller Electric making welders.

A New Owner Takes Charge

The Corvette was sitting and had not yet been purchased from exauto instructor Dave Sarna, who had maintained ownership of the car. When Sarna signed up for a church mission in Ireland, he realized his best option was to put the car up for sale on Craigslist. The posting got a lot of response but the offers were a bit too low until Sarna and Ryan Phillips negotiated a deal.

Phillips said his father—Gary Phillips—had owned a Corvette around 1975. Years later he worked for a company called Fond du Lac Bumper Exchange in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin—a job that put him in touch with many body shops, including one that may paint this Corvette. Gary had also owned three earlier Corvettes…a ’62, a ’67 and (Ryan believes) a ’72.

But Gary Phillips and his wife Kathleen (Ryan’s mom) decided to sell their Corvette due to the pending birth of Ryan’s older brother. Ryan is now 31 years old and decided to buy and fix ’77 Corvettes for both of his parents. When he bought Dave Sarna’s orange car, he already had a black ’77.

Some Quick Progress

The big problems with the orange car were that Heidi had taken it almost completely apart and that some rust had been found in the passenger side metal floorboard.

Enthusiasts who are familiar with the idiosyncrasies of ’77 Corvettes know that this rust is caused by leaky T-Tops and almost always means that the frame and frame gussets are also rusty to one degree or another. The downside of this is the cars usually need frame repairs; the upside is that the cars are affordable.

Ryan Phillips had to keep his project as affordable as possible. So he specifically wanted to build two 1977 Corvettes for his mom and dad. When he bought the orange car, the black one had already been built. The orange car was picked up on May 6th. At that time, Ryan told us that the car would be put back together within two weeks. He actually beat that goal by about a week.

On May 10, Ryan sent an email message: “Here are some more pictures of my progress. The radiator is back in and all the hoses are connected. The floor is blasted, primed and painted.” When Ryan worked on the floor, he also welded up the bad spots in it. He re-installed the hood on the car and did an extra four hours of paint buffing. “There is a long ways to go, but it’s a start,” he said.

“The car is running, the interior is in and the original motor has an Edlebrock carburetor, valve covers and air cleaner,”

Ryan wrote on May 16: “It has taken every night since I got it to assemble it. The Corvette is an evolving project, but it is roadworthy again.”

In a May 17 email, Ryan added, “I am going to be putting headers and an allnew exhaust system on the car today.”

Some Work Now…More Later

Ryan’s first goal was to get the Corvette back together so his father can drive it this summer. Next winter, he will take it apart, restore it and make a few improvements. He had planned to replace the orange Corvette’s engine but now that he has it running well he’s decided to stay with the original numbers-matching 350.

Meanwhile, he removed and sold the 383-cid stroker engine that was in the black Corvette and will replace it with a 350-cid Chevy V-8 with fourbolt rods.

Ryan says he has been working on cars since he was 12 years old. “If you ever need help, let me know,” he offered. “It’s really my passion. I have put lots of stuff together,” he pointed out. “It’s all just nuts and bolts.”

As you’ll see in the accompanying photos, Ryan’s quick work got what looked like a wreck of a Corvette back on the road in less than two weeks. We plan to revisit this project next winter when the car is again disassembled and then restored from “driver” to show car condition.

Meanwhile, here are some tips to help you keep going with your project when the going gets tough.

Some Insight and Experience to Keep In Mind

The dream of restoring a car is one shared by many enthusiasts. But the reality of disassembling a car, refinishing all the pieces and putting it back together again is a whole other thing. Depending upon how much work you do yourself, this kind of project can require bodywork skills, mechanical aptitude, an understanding of auto electrics and project management planning.

Often there’s a point in time between taking the car apart and reassembling it properly where restorers tend to “run out of steam” and lose sight of their long-term goal. When the enthusiasm for a project starts to settle down it becomes important to rekindle the original spirit that got the job going in the first place. Restorers we have interviewed over the years have different methods for maintaining the self-motivation needed to keep their projects going. Here are some of the tips we’ve received from successful collector car rebuilders over time:

LarryFechter, Managing Director of the Iola Car Show (www.iolaoldcarshow.com) teamed good organization with an “it’s my hobby” attitude to finish his every-nut-andbolt restoration of a ’69 Camaro Z/28. A former facilities director for a school district, Larry entered each part removed from the car into a computer database with a number and stored the parts in cabinets with matching numbers. This allowed him to track every part involved in the four-year project. Larry would also say, “I don’t hunt, I don’t hang out in bars, I don’t watch TV and I don’t snowmobile. Restoring this car is my hobby and you have to have that kind of thought process to enjoy restoration work.”

Dan Pankratz, a member of the Fox Cities British Car Club (www.foxbrits.com), secretly restored an MG TD for his father, whohad dreamed for years about rebuilding the car. Dan’s method of getting the job done was to “do something every day, no matter how small the job was.” After working all night at a printing plant, Dan would go to the shop where the car was and do something to make it a little more complete that day. The reward came when the car was wrapped with a big bow and given to his dad as a Christmas present.

Fred Beyer of Hot Rod High (www.hotrodhighusa.com) developed a program through which students, working on their own time, built and restored old cars as part of an afterschool student motivation project. A piano player, Fred made up tunes like the “Oil Change Song” to turn the job of working on the car into a fun, entertainment experience. Fred thinks that most restorers do better when they make the job entertaining.

Les Jackson, who wrote about restoration for Hagerty Insurance (www.hagerty.com) said it’s important for restorers to budget their time. “No matter what you think might be the case, a full restoration of virtually any vehicle will take you two years or more unless you give the car to a professional restoration facility,” he pointed out. “Even if you are retired and can work on the project every day, the total time necessary (typically 1000-1500 hours for experienced hobbyists) to take a car apart, restore each component and put it back together will drag out. It should, so let it! After all, this is a hobby and it’s supposed to be fun, right? More to the point, rushing a restoration always results in the expenditure of more money. You lose the ability to patiently ‘shop around,’ you pay higher fees for services and find yourself buying on impulse. If you’re not having fun you’re doing something wrong.”

Richie Clyne of Clyne’s Classic Cars (www.clynescars.com) in Las Vegas, once ran a car restoration program in a prison. At that time he also was director of the Imperial Palace Auto Collection in Las Vegas and part owner of The Auction. When a restoration was completed, the car would be taken to The Auction and sold. Richie would then take photos of the auction process back to the prisoners along with the selling price. This showed the men the value of the work they had done and made them anxious to start on the next restoration project.

Fox Cities British Car Club (www.foxbrits.com) was formed in 2001 around the theme of “Members Helping Members.” In the beginning, members would gather on Saturday mornings to work on cars together. Eventually, club members bought an old motorcycle shop and turned it into a restoration and storage facility complete with a pub, library and a meeting room.

Bill Kroseberg initiated a Goal Based Education Program (featured in the April issue) for students at Waupaca High School in Waupaca, Wisconsin. The goal is the restoration of a ’67 Camaro. It began when another class was developed that focused on building a house. “We figured if they could do a house, we could do a car,” Kroseberg said. Realizing that students have a variety of skills helps keep them motivated. “We match their skills to the needs of the project and that helps keep things on track,” Kroseberg said. “Students like to show their co-workers what they can do well.”

Robert G. Rippberger, owner of TLC Restorations (www.tlc-restorations.com) in Milton, Wisconsin, developed a scientific way to document restoration costs and therefore keep better track of the jobs flowing through his shop. Rippberger dissected what a “rotisserie” restoration involves in terms of car disassembly, bodywork, paint, mechanical and electrical repairs and re-assembly. According to Rippberger, the typical process and average time for a complete frame-off restoration of a mid-sized GM performance car includes nine processes with a total typical time ranging between 395 and 550 labor hours. Armed with this breakdown of tasks and time Rippberger can do a much better job of managing each restoration project.

Got any tips to keep a restoration going? We’d like to share them with other readers.