Between Carlisle & Hershey

If You Plan to Visit Both Meets, There’s Time Between Them. Here’s a Few Side Trips to Help Fill In the Gap.

THERE’S NO SHAME in needing a break from days and days at Fall Carlisle (Oct. 3-7), Fall Hershey (Oct. 10- 13) or both and the region offers more alternatives than shopping and eating. Some are obvious while others are unlikely to be discovered by accident, but four representative destinations illustrate the possibilities.

Roadside America

Most who arrive at the meets from the east have passed Roadside America along I-78/U.S. Route 22 in Shartlesville, Pennsylvania; it’s been there since 1953, two years before Hershey began and a survivor from the time when I-78 was a plan and U.S. 22 wasn’t limited access.

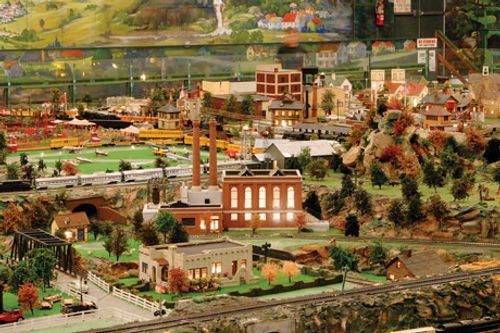

Billboards describe it as a “miniature village,” which is like saying that General Motors built some cars last month. The “miniature village” rests on a platform measuring 6000 square feet and according to a brochure, includes 300 handmade buildings, 10,000 handmade trees, 4000 figures and 2250 feet of railroad track, thus explaining the sign telling visitors to “be prepared to see more than you expect.”

By the time Roadside America reached its current location, its builder, Laurence T. Gieringer, had been sharpening his skills for roughly two decades. His granddaughter, Dolores Heinsohn, has two letters that probably convinced him to forge ahead and make his model making into something for the public. The letters are from judges who had viewed his work in a Christmas contest—his display won first prize—sponsored by The Reading Eagle in 1935 and both encouraged him to do more. One suggested that other craftsmen would be inspired and the other hoped that Gieringer would “go further with this yard and realize something for your time and expense.”

By 1941, the growing display was housed in a rented dance hall along old U.S. 22, the two-lane replaced by today’s alignment, and period photos showa luncheonette, gas pumps and something else.

“You can see the old cars,” Heinsohn said. “This looks like a carshow, but it’s not. It’s the real deal.”

Shartlesville and Roadside America, though, would soon change.

“A friend of (my grandfather) said he should get out of renting and have a place of his own,” Heinsohn explained. “(My grandfather) said he didn’t have the money and his friend said ‘I’ll lend you the money to buy the property and to build the building.’ This wasn’t built until ’53,so from ’41 until ’53, it was on old 22. But he knew ahead of time where the highway was going to go and he knew exactly where to build the building.”

A new building along a new four-lane highway should have guaranteed Roadside America a long and happy life and it seemed that would happen. But in about 1960, the road was made limited access and the parking lot was fenced. Heinsohn said it hurt, but added that today’s speeds and traffic would make pulling into the lot impossible anyway. On the other hand, Roadside America is still open,still attracting visitors and still looks very much as it did in 1953. (These days, the Shartlesville exit and “impossible-to-miss” signs lead drivers to it.)

Heinson’s grandfather died in 1963, but she said that if he were to walk through the door today, he’d approve.

“I think so,” she observed. “Like I always say, I don’t make big changes. I make small improvements. I redid the trees and we clean it and put fresh grass down. But as far as the buildings, the figures, every single thing isin there and you can look in (old) pictures and see these pieces.”

By itself, keeping everything intact would be impressive, but Roadside America Isn’t a static display.Creeks and waterfalls flow, trains and trolleys operate, an airplane circles overhead and figures go about their business. It all depends on—among other things—five electric pumps moving 6000 gallons of water per hour, eight motors, 96 control switches and 21,500 feet of wiring, according to a brochure, but there’s more. Just as it’s not static, it’s also not programmed; buttons on panels along the perimeter walkway allow visitors to operate various pieces of equipment. Finally,the light gradually changes from day to night and an unabashedly patriotic pageant of traditional values unfolds via projection and sound.

With all of that, it’s almost impossible to miss that Roadside America is a piece of mid-twentieth-century car culture almost perfectly preserved, and stopping at Roadside America is like walking into travel history.

Ferry Across the Susquehanna

Another way to experience the past is to cross the Susquehanna River on the Millersburg Ferry. Ferrying isn’t a lost art and the Susquehanna isn’t the Mississippi, but Millersburg’s operation can make some important claims.

“They’re the last ferry boats left on the Susquehanna,” said Captain Craig Hershey, “and the last wooden stern wheelers left in the United States, the last two.”

That came to be through a combination of location, timing and generosity. The ferries carry vehicles and pedestrians betweenMillersburgatthe endofU.S.209 and a landing near Liverpool along U.S. 11/15. Competitors are long gone, but the Millersburg Ferry’s location—the nearest bridges are 14 miles downstream and 27 miles upstream—helps to explain how it’s survived to become Pennsylvania’s oldest operating transportation system and why it’s more than a tourist attraction.

“This actually was founded in 1817 as a ferry system,” said Jim Bullock, chairman of the Millersburg Ferry Boat Association. “They poled. And then that continued in that capacity—private ownership—from 1817 until 1990. It changed a number of hands during that time and the last owner was a man by the name of Wallis. He wanted to get out of the business,so he put it up for sale and the local bank, Community National Bank, bought the ferry boats and turned them over to the community.”

The association today handles the operation, which includes the landings, the ferry wall across the river and the boats themselves, both diesel-powered and both capable of carrying four vehicles and walk-on passengers. The Falcon III was built in 1918 and the Roaring Bull V was rebuilt in 1998.

“When we say ‘rebuilt,’” Hershey explained, “we mean that at that point, everything was in such bad shape that it wasn’t worth repairing anymore. We replace all the wood and transfer all the hardware, all the metal. In between those (rebuilds), we’re always replacing planks and individual pieces.”

Bullock said either ferry or both might be running on a given day, crossing roughly parallel to the ferry wall that slows the river enough to ensure sufficient depth. The wall, like the boats, requires maintenance by the association.

“In the early days,”Bullock said, “the wall was laid up by hand. Then they went to a bulldozer in the 1940s and the last couple of contractors used trackhoes.”

“Straight across is almost a mile,” Hershey said, “but no matter which way we go, we go at least a mile-and-a-quarter just to get through without getting stuck on the bottom. We’ll take up to four cars across the Susquehanna and depending on how much water we have is how fast we get over there. Today, it’s taking maybe 25 minutes because we’re running out of water and it’s very low. The bottom line is that sitting still, we need about 15 inches of water to float and as we go along, we might be drawing 16 inches at 800 rpm. The faster we go, the more it’s going to squat and the more we’re going to draw. With the water as low as it is now, we have to go slow.”

Hershey has eight years on the ferry— five of them as a captain—and said winds and currents mean every trip is different. Spring high water changes the Susquehanna into a different river, he added, but experience makes his job easier. Note that he didn’t say it becomes easy.

“I always say it’s a lot like riding a motorcycle. Don’t ever think you’ve got it down.”

And those who doubt that anyone really uses the ferry for regular transportation or simply happens upon it might consider Hershey’s experience.

“We get a lot of people with a GPS,” he said. “We’ll come down (to the landing) and there’ll be a guy sitting here with a blank stare on his face. He’ll say ‘It says to come down and take the ferry.’”

An Arresting, But Little Known, Museum

Veterans of Fall Hershey might show a comparably blank stare when told of the Pennsylvania State Police Museum, even though it’s within walking distance of the flea market.

The “front hill”is Academy Drive to the State Police Academy and, unfortunately, the museum is off of Swatara Road. It’s not well-known and it’s not large—yet— but finding it is worth the effort.

“I think people are surprised at how much we can get into the space that we have,” said Curator Samantha Christopher, “and once we tell them that we’re a non-profit and not state-funded, they say ‘wow, that’s great that you have the opportunity to do that.’ We’re trying to expand, but money’s tough right now.”

Limited space means the 1973 Plymouth Fury police car is parked outside and covered as necessary, but it doesn’t mean the museum has just a few items on display.

“We’ve got a ’62 Harley and a lot of weapons,” Christopher said. “We’re actively working on an exhibit of the weapons that were used; we just got two shotguns in and we’re also getting a Beretta and a Glock. There’s the mockup of the cadet bedroom, uniforms and we try to do memorials for the officers killed in the line of duty.”

Exhibits also recount some crimes that caught public interest,such as one involving the 1980s Pennsylvania Lottery.A state lottery official and some workers at a television station that broadcast lottery drawings modified some of the balls used to pick the winning numbers, bet heavily on the resulting possible combinations, cashed in when 666 was drawn and were caught.

“There’s a lot back there where you’re seeing the actual objects,” Christopher said. “We have the lottery balls.”

The unusual crime provided the basis for a movie, “Lucky Numbers,” but she said the most popular exhibit with visitors focuses on the rodeo sponsored by the state police.It was last held in the 1970s.

“When you see the old photos and you look at the crowds they would draw,it’s unbelievable,”Christopher said. “Thousands and thousands of people. It was a prestigious thing if you tried out and got picked to be on the rodeo team. I didn’t know that existed until I started working here…”

The museum still plans to have a larger building so that more of the currently stored pieces could be displayed for those who want to have a closer look at part of the law enforcement community.

Have a “Small Town” Experience

Looking around would be just as worthwhile in Pine Grove, where a 100- year-old theatre graces a main street that could be a movie set. However, it’s not a tourist town, according to Borough Secretary Judy Kassab, and anyone who appreciates a small-town atmosphere would recognize that, just as the residents do.

It is, she explained, a town where weekends and evenings see people walking around or sitting on front porches, but it has changed in other ways. The Union Canal is long gone as are several mills, an ironworks and in more recent years, sewing factories and the railroad.

“We had a huge tannery at one point and that’s no longer there,” Kassab said. “This area (near the borough building) was a brickyard.”

The Pine Grove Theatre, though, is alive and impossible to overlook. Built in 1910 for live performances as the Hippodrome and then updated to show movies, it closed in 2000 and its current owner clearly remembers how she learned that it was available.

“I stood across the street at a Halloween parade,” recalled Louise Miller, “and it said ‘for sale’ on the marquee.”

She and her then-husband talked about the possibilities and about contacting the owner. Finally, they made the call and after seeing the interior, the agreement was signed and friends helped with the initial cleanup and trash removal. The building required help, but there was a bright side.

“Almost everything we needed to put things back in operating condition was here,” Millersaid. “(The previous owner) never got rid of anything, so everything was in the building. We opened April 13, 2001 with Tom Hanks’ ‘Castaway.’There was such a hubbub about us opening. We had TV reporters here and people were lined down the street, waiting to get in. It was a really good thing.”

Surprisingly, given its exterior appearance, the Pine Grove Theatre has two screens with “the big theatre” seating about 250 and the smaller basement screen playing to 38, numbers that explain why Miller takes reservations.

As built, it held about 400 people and had a balcony, dressing rooms, the stage and large windows on its sidewalls. If a patron from those earliest years somehow showed up today, Miller said, he wouldn’t recognize the interior, but the exterior would be a different story.

“If you look at the pictures I have from 1910,” Millersaid, “the marquee is what’s new there. The façade? Nothing’s changed as far as that goes. There were a couple of more ornate things along the roof and the ticket booths were outside.”

The area around the ticket booths was rearranged, but one important feature remained in place to be discovered and adapted on the road to reopening. Glass blocks in the floor had allowed daylight into downstairs rooms, but in one of the renovations, they’d been covered with carpet on their upper side and with false ceilings below.

“Now,” Miller said, “I’m going ‘these are glass blocks? How cool is this? We’ve got to use them.’”

Today, green bulbs below illuminate the glass, an effect that’s enhanced by keeping the overhead lights dim. It’s one of the reasons why patrons tell Miller that “you don’t see theatres like this anymore.” Some of them drive an hour or two, some are passionate about old theatres and some just find it.

Non-residents might make more of a fuss, but the locals appreciate what they have with the theatre. Aesthetics aside, the Pine Grove offers family nights with special pricing, shows on days when kids aren’t in school and the telling subtlety that Miller rarely talks about her “customers”—instead they’re her “people”— and it works.

“Last night,” she said, “we were running our tails off. People were lined down the street, waiting to getin.”

The theatre is a good fit to the mostly residential area surrounding it and to Pine Grove in general, but it’s not the only reason to visit.

“You need to explore,” Kassab emphasized. “You have to like the whole small town life and can’t be afraid to get off the main road and explore a little bit.”

Plan Before You Go

The four destinations featured here could be visited in a single day, but not easily. The Pennsylvania State Police Museum, the Millersburg Ferry from west to east and then the Pine Grove Theatre are possible in one day as are the museum, Roadside America and the theatre, but there are details to consider. The ferry is weather-dependent since it can’t run when the Susquehanna’s level is too low, finding the museum can be a challenge and exploring in a collector car brings additional points. In short, think hard before setting out in a vehicle whose strong suits aren’t adequate power and strong brakes. Traffic on the roads from the Carlisle-Hershey area to the ferry landing on the Susquehanna’s west shore can be heavy. U.S. 209 between Millersburg and Tremont is hilly, although Pennsylvania 125 from there to Pine Grove shouldn’t be a problem. From Pine Grove south, Pennsylvania 501 is also an up-and-down road to Bethel, where Interstate 78/U.S. 22 leads east to Roadside America. A GPS unit or good map is a necessity, but there’s one final piece of advice.

There are shortcuts and intriguing back roads between some of these destinations and despite their innocent appearance on paper, they can be difficult and at least one will fight even modern cars. With the exception of old Route 22 between Bethel and Shartlesville— signed as “Old Route 22” in some areas and obvious for the most part—following them could open up a new adventure.

Directions and information on schedules and costs are available as follows.

Roadside America: roadsideamericainc.com;

Millersburg Ferry: millersburgferry.org;

Pennsylvania State Police Museum: psp-hemc.org;

Pine Grove Theatre: pinegrovetheatre.net/home;