Planning the Right Ford Flathead V-8 Build

Do Your Homework Before You Reach for a Wrench…and You’ll Be On the Right Path to the Flathead You’ve Always Wanted.

Editor’s note: Since there were several types of Ford Flathead V-8s built during the engine’s two-decade production run, a restorer has a number of options open when it comes time to select and rebuild one that’s right for his vehicle and driving habits. The following material, excerpted from the book “How to Rebuild & Modify Ford Flathead V-8 Engines,” will help to guide you through your project. As an aside, you’ll recall that Jim Richardson, our Mechanic on Duty writer, started his own flathead V-8 rebuild in the March issue only to find three cracks in his block. He now says he has a line on another engine and hopes to resume his project soon.

All Flatheads Are Not the Same

As you’ve seen in Chapter 1, there are several distinct generations of the Ford Flathead V-8 characterized by both small and major differences. As a result, not all engines are suitable for all applications.

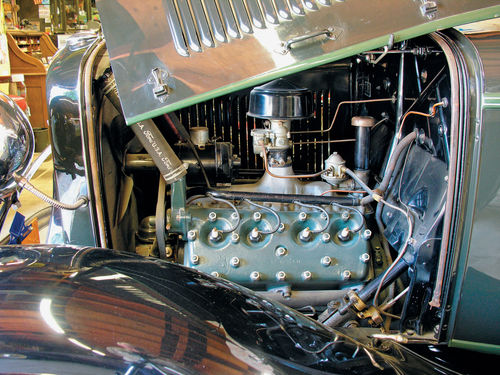

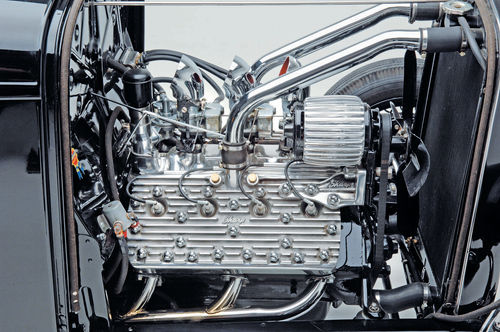

There is a broad range of options available to the flathead builder, from a dependable 21-stud stocker all the way to a big-displacement blown fuel motor. The hardware path you choose depends on your needs and your resources. For example, if your need is for a dependable, good-running engine for a 1932–1936 tour-quality passenger car or truck, one that looks like it belongs in the engine compartment, there’s no need to expand your search beyond the several years of 21-stud engines. If you have one such engine that’s a bit tired and needs rejuvenation, so much the better.

If your goal is a budget-constrained traditional hot rod engine with a bit more horsepower than stock while retaining good drivability and economy, you can find the popular center-spigot-head look with a 1937 21-stud engine as well as the early 24-stud 221-cid engines (1938– 1939). If you’re looking for substantially more power, you’ll need to ramp up your budget and start with a 239-cid engine that will accommodate a meaningful increase in cylinder bore along with an increase in stroke.

If a serious race engine is your need, prepare to open your wallet wide. You’ll need the very best block you can find as well as race-quality internal bits and flathead-familiar machine-shop services.

Selecting the Right Hardware

Planning a flathead build is rather like planning a trip to the salad bar in your favorite restaurant—or your entire meal in an Eastern restaurant faced with row upon row of a la carte choices on the menu. Everything looks so good but is probably not as tasty and satisfying when indiscriminately selected without much thought given to complementary flavors and textures.

We’re taking an a la carte approach to selecting flathead hardware for your build with recommendations and guidance for determining what goes with what.

Block

The biggest piece, the block, is the most important element in determining what type of engine you want to come out of the other end of your build pipeline. For an early 21-stud engine without the constraints of year-correct numbers, a late 1936 LB block, indicating large insert crankshaft main bearings in place of old-style poured babbit bearings is an obvious choice for an economical and efficient rebuild. And you could also slip in a 1937 block, where the water pumps moved from the heads to the block, add a pair of water pump block-off plates, and top the block with some early water pump heads that would fit the 21-stud block just fine. No one’s going to rag on you for these sensible Ford-guy upgrades.

These first-generation engines (1932–1937) had 21-stud blocks with a 3 1/16-inch bore. We suggest limiting overbore to 0.080 inch or less because the castings are a bit thin in some areas.

Early second-generation 24- stud Ford blocks, 1938–1942, are limited in their bore-size potential, although they will accept stroked crankshafts, both full-floating and locked-insert connecting rod bearing types. While they will accept overbore of 0.080 inch or greater, they start life with a 3 1/16-inch bore. They will also accept all the speed equipment available for this configuration, including cylinder heads, intake manifolds, headers, ignition, camshafts, and valve gear. Mercury blocks started out at 239 cid and willingly accept large overbore.

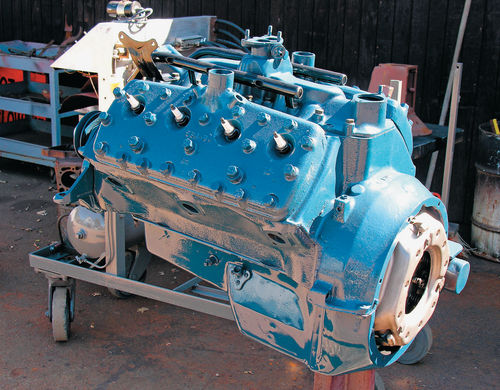

The late second-generation 59A blocks of both Ford and Mercury (1946–1948) have been the clear-cut favorite of rebuilders and hot rodders since they first appeared. With a standard bore of 3 3/16 inch for both Ford and Mercury, they can be bored and stroked easily to the 300-cid range and greater, although with the cost of service life and cooling.

The third and final generation (1949– 1953) of blocks—Ford 8BA and Mercury 8CM—are arguably the most desirable for building, particularly as hot-rodded engines. They are the newest in terms of manufacturing dates and more likely to be in better condition. Their cooling system is substantially improved over that of the earlier generations. And the absence of the cast-in-place half bell housing offers more modern and affordable transmission options.

If you’re prepared to step up to a new block with no old baggage to deal with, consider the French block (made in France for French military applications). But don’t think about one for too long; they’re in a short and finite supply and won’t be manufactured again. Available from So-Cal Speed Shop Sacramento, the blocks are provided in three stages of modification: from $2750 for the Stage 1, which is unmodified but has all the homely military-related protuberances expertly pruned off so it will fit stock Ford firewalls, to $3750 for the Stage 2, which has essential street-performance hot rod upgrades, to the Stage 3 for $4350, which is a near race-ready block. The French blocks are definitely for the long haul, for building an engine that will rival modern engines for longevity.

Crankshaft and Connecting Rods

From a practical standpoint, first-generation engines are relegated to later first-generation crankshafts with full-floating connecting-rod bearings. Second-generation engines can use either the full-floating bearing-style crankshaft and rods or the third-generation engine crankshaft with locked-insert bearings and connecting rods. There’s a caution here: Locked-insert bearings can’t be used on crankshafts designed for full-floating bearings; the locked-insert-bearing crankshafts have two sets of oil feed holes on each journal, one for each connecting-rod bearing. The full-floating crankshafts have a single set of oil feed holes on each journal that supply the full-width bearing that accommodates both connecting rods. Full-floating bearings can be used on crankshafts with two sets of oil-feed holes, however, and frequently are in race engines where the reduced drag of the full-floating bearings is desired.

In addition to the 4-inch-stroke third-generation crankshafts from 1949 to 1953 Mercury engines—increasingly hard to find in standard or under-10 condition—SCAT and Eagle sell new stroker crankshafts and heavy-duty standard and H-beam rods, with strokes of 4.0 inches, 4.125 inches, and 4.250 inches. A complete assembly—crankshaft and connecting rods—will cost you a little north of $1400 and should be considered essential to a high-output supercharged engine. For less performance needs and less horsepower potential, and a little more than a third of the price of a complete stroker assembly, So-Cal Speed Shop Sacramento will sell you a new 3 3/4-inch French crankshaft and new 8BA style connecting rods for just $525. (Eagle Specialty Products, Inc. is in Southaven, Mississippi. Visit eaglerod.com. SCAT Enterprises is in Redondo Beach, California. Visit scatenterprises.com. So-Cal Speed Shop Sacramento in California can be reached at socalsac. com or .)

Pistons

Your options for pistons range from OEM-style cast four-ring, to cast and hypereutectic three-ring style, and finally to forged three-ring high-performance pistons. The four-ring type is favored by many restorers while cast three-rings are the more popular with folks building stock to street-performance engines. Forged pistons are essential for highperformance engines, and especially those that are supercharged.

Regular-cast and cast hypereutectic pistons that have a low coefficient of expansion can be fitted with tighter clearances than forged pistons that expand more, requiring greater fit clearance that results in greater noise at startup and until they’ve reached operating temperature. If there’s no performance-dictated reason for choosing forged pistons, we recommend cast units instead.

Camshafts and Valvetrain

More than any other single element, the camshaft determines the character of your engine. A mild “3/4 race” grind will wake up a stock bore-and-stroke engine, with maybe a second carburetor added and a bit of material milled off the stock heads, to feel like half again as much horsepower as you had before. It’s not, of course, but that’s the nature of what the camshaft can do.

“Too much cam,” a grind that is too aggressive for the engine’s potential, as well as your needs, can spoil the experience and create a wholly unpleasant engine with poor drivability as well as subpar performance. It comes down to balance, a camshaft that suits your needs and is appropriate for the modifications to your engine. And whatever you do, don’t choose a camshaft because it has a lot of “lope” at idle and sounds “really bad”; you can get the same effect that posers got years ago by pulling out your choke as you idle into the drive-in or cruise-night parking lot. You’ll get the lumpy sound you’re after, but you won’t have to live with the poor drivability and terrible fuel economy of a really “bad” cam.

Before selecting a camshaft, we recommend you call the tech line of several cam specialists, including Iskenderian and Schneider. They know their products better than anyone and have no reason to sell you anything other than what you need.

Cylinder Heads

Original cast-iron cylinder heads, properly cleaned and milled (no more than 0.010–0.020 inch), will increase the compression ratio an acceptable amount without appreciably hurting flow. The combustion-chamber shape of most of the Ford heads is good, better in fact than some of the aftermarket aluminum heads of the past. And that brings us to another issue: the use of vintage aluminum cylinder heads. Fewer and fewer usable early aluminum heads are turning up these days. Most we’ve seen in recent years require repair, usually major welding and machine work. Depending on how many times in the past they’ve been milled to true them up, they’re likely to require re-doming. Unless you have your heart set on a particular set of vintage heads, we recommend purchasing new aluminum heads from one of the several current manufacturers. You’re likely to be money ahead in the end.

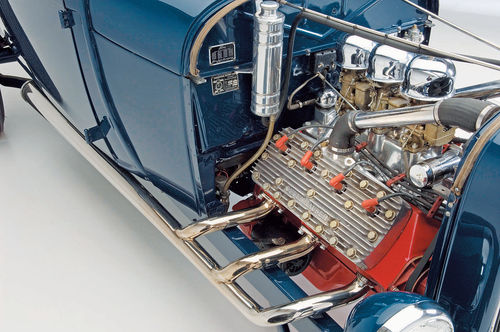

Carburetion and Intake Manifolds

For any flathead engine no larger than 255 cid and a street-performance application, two carburetors are all that’s needed, and all that can be used, for that matter. Three- and four-carburetor setups are usable only on large-displacement engines and then necessary only in racing applications. Three-carburetor setups, including for large displacement engines on the street, are inclined to poor drivability even with progressive throttle linkage. Fuel economy is poor as well in urban driving and doesn’t improve much on the highway.

Dual-plane multiple-carburetor intake manifolds are mostly all good, generally based on the design first developed by Ford. Early after-market open-plenum manifolds found at swap meets and on the Internet should probably be avoided because of the poor drivability that’s characteristic of the design.

Matched four-barrel carburetor and manifold systems from Edelbrock and Speedway offer good drivability and economy for less money than a dualcarburetor system.

Ignition

Ignition choices are simple: mechanical breaker type or electronic. The tradeoffs are covered in Chapter 9 on page 188.

Supercharging

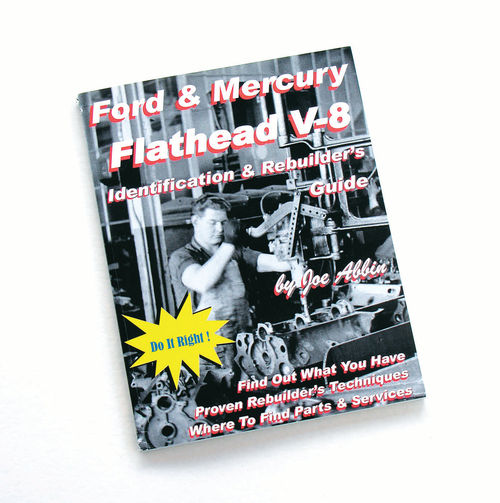

Supercharging the Flathead Ford V-8 is beyond the scope of this book. To cover the subject in a meaningful and valuable way would require a book of its own, and such a book exists—actually two books. Joe Abbin at Roadrunner Engineering has been a strong advocate for building streetable blown flathead V-8s that admirably acquit themselves on the drag strip as well. Abbin’s first book, “Blown Flathead,” published in 2000, is out of print, but his latest book, “Flathead Ford V-8 Performance Handbook,” published in 2009, expands on the information from the early book with developments and data acquired in the nine-year interim. (RoadrunnerEngineering is in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Visit roadrunnerengineering.com.)

Where and How To Buy What You Need

One-stop shopping for flathead V-8 hardware and speed equipment is still possible today as it once was with companies such as Speedway providing just about all you need. But there are also a great number of specialists to consider for carburetion, camshafts, crankshafts, heads, manifolds, and NOS hardware. You’ll find them in Appendix B on page 203 of the book.

Editor's note (cont.): “How to Rebuild & Modify Ford Flathead V-8 Engines” covers “every aspect of buying, building, and owning a flathead V-8.” The 208-page softcover book has 531 color and 8 b/w photos, and is available from Motorbooks (motorbooks.com). The MSRP is $35.