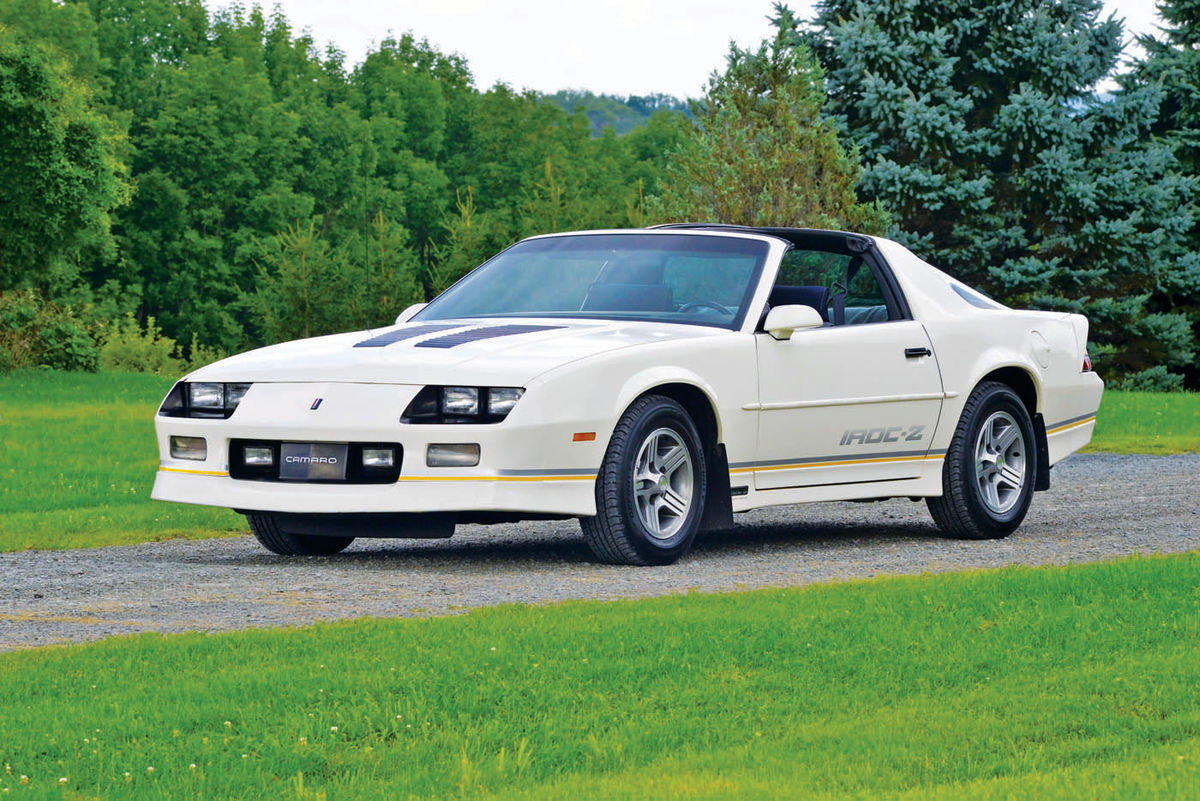

1989 CAMARO IROC-Z

Speaking Up at the Right Moment Brought This Camaro Into His Garage. Now the Next Owner Is Waiting for Her Turn Behind the Wheel.

Editor’s Note: Although Auto Restorer’s 30th Anniversary Isn’t Until June, We Thought It Would Be Nice to Start the Year With a Car That Hit the Streets at About the Same Time That Our First Issues Were About to Come Off the Presses.

It never really hurts to ask whether a car might be for sale, even if the immediate answer seems likely to be an emphatic “no.”

“I met a fellow at a car show,” recalled Frank Lopatofsky, whose 1989 Camaro IROC-Z is featured here. “We were there discussing cars and Camaros. I saw an IROC pull in when we were sitting there and I said ‘boy, I’d like to find one of them.’ He said ‘I have one at my house. I just bought it.’

“I said ‘do you want to sell it?’ He said ‘no, I’m going to take it and make a pro-street out of it.’”

As answers go, that one seemed to qualify as being close to an emphatic “no,” but Lopatofsky had at least asked the question at the April 2016 show.

Two months later, he learned that maybe the “no” hadn’t been that emphatic after all.

“He came to a show in June,” Lopatofsky continued, “and he said to me ‘I want to sell that car.’ All of a sudden, he was changing his mind.

“My wife went with me to look at the car. I went there, saw the car, took it for a ride. We didn’t even go around the block and my wife said ‘we’re taking it home.’”

Chevy vs. Ford

Their interest and their quick decision are easy to understand for two reasons. The first is that Lopatofsky already knew Camaros, thanks in part to the 1981 Z28 that had been in his garage since 2010. The other is that Camaros have exercised a strong appeal since the model’s introduction for 1967 as Chevrolet’s Mustang-fighter.

With their nearly identical measurements—108.1-inch wheelbase and 184.6-inch overall length for the Camaro versus 108 and 183.6 for the Mustang—and similar long-hoodshort-deck proportions, the surprise is just how well Chevy succeeded in making its comparable new model feel different.

The Mustang for 1967 had been seriously updated, but Ford had wisely been careful to maintain the look that had been so instantly and astonishingly successful. Sharp edges, straight lines and plenty of detail in everything from the now-threelens taillights to the side-panels’ coves to the slightly forward-leaning grille opening with its chrome-framed mustang guaranteed instant identification. The Camaro, meanwhile, was smooth and curvy with—at least in profile—a family resemblance to the Corvair. Edges were soft, lines flowed and both the grille and the taillights were simple.

Putting aside the most unyieldingly passionate badge-loyalists, ugly cars are unlikely to be big sellers in the enthusiast segment, so the Camaro’s appearance was not something to be taken lightly by Chevy and promotional material, while perhaps vague, was unmistakable in its message. The Camaro was “a freshly styled example of how fine an exciting road machine can look. Both models—convertible and sport coupe—have the long sportscar-inspired hood. The body styling sweeps your eye astern. And from the rear, Camaro’s stylistic freshness sets it apart from the mundane.”

Adding More Power to Camaro’s Appeal

Like its competitor from Ford, a Camaro could call a driver with nothing more than its visual impression and then meet nearly any demand that driver might present to it.

Under that attractive skin, a Camaro could be an uncomplicated everyday car with nothing more than a 140-horsepower, 230-cubic-inch six and a three-speed manual transmission. Chevrolet promised that “the basic six won’t be found wanting” and few would have argued that a Chevy six was anything less than bulletproof, but then as now, some drivers wanted much more. For them, the bigger six wouldn’t do, nor would either the 210-horsepower or 275-horsepower 327. The choice was obvious, “an entirely new Chevrolet V-8, the 295-horsepower Turbo-Fire 350… exclusive to Camaro.”

As the model year went on, advertising explained that “Chevrolet’s free-breathing Turbo-Jet 396 V-8 just begged to be put into Chevrolet’s newest sporting machine, the Camaro. So we did it.”

The Camaro might well have continued on that track, successfully relying on the 375-horsepower SS 396 to satisfy the demands of the performance-oriented drivers while also providing some reflected glory for those whose priorities were style or value.

A Slow Start for the Z/28

The trouble, though, was that the Sports Car Club of America’s Trans Am series was tempting and it didn’t take long for some creative thinking at Chevy to see what might happen with careful planning. Using a 283’s crankshaft in a 327 block produced a 302, about as close as possible to the series’ maximum-displacement limit of five liters or 305 cubic inches, and picking the right components from the parts bins enabled Chevrolet to give the new engine a rated 290 horsepower. Better suspension naturally produced better handling and both a four-speed and power front disc brakes were mandatory.

It was the Z/28 and it proved to be a great concept nicely executed, but there was one major flaw and it had nothing to do with the actual car as for whatever reasons, Chevrolet just didn’t promote the Z/28. The result was predictable—a mere 602 examples were sold during the first model year— and the result of that was equally predictable.

“Closest thing to a Corvette yet,” promised advertising for the barely changed 1968 version. “Special order a Z/28 and you get a Camaro that comes on like a Corvette for a lot less,” a clearly attractive pitch that helped to generate 7198 sales during the Z/28’s second year. More importantly, the number of sales was a hint that the Z/28 was entering into a long life.

Take Your Pick From a Camaro Assortment

Like all muscle cars, the Z/28 appeared on the market at the right time. Young drivers wanted to go fast and since there was no shortage of young drivers in the second half of the 1960s, Chevrolet and the rest of the industry worked hard at developing and selling the cars they believed would be the ones that generation wanted to drive. That they were successful as a group was proven by sales of both the muscle cars themselves and their lesser versions that shared the same basics. The automakers, as they do today, understood the value of high-end and performance models when it came to selling the mid-level and economy models. A 1967 ad pictured the “Camaroabout-town” with its “fully synchronized three-speed. Very civilized Six,” the “Country-club Camaro. Rally Sport with hideaway headlights and standard V-8, 210 horsepower” and “Camaro-the Magnificent. SS convertible, now available with 396 cubic inches, 325 horsepower!” All were Camaros and to many, that was all that mattered.

Since the competition was doing roughly the same thing, the drivers across the board were the winners. Realistically, there were no losers because any driver with enough money could buy the Camaro of his dreams and every version of the Camaro scored equally in terms of being a good car.

The Z/28 and its competitors were winners, too, but that fact produced losers by radically changing drivers’ tastes. What had been the typical performance cars— the Chrysler 300 letter series, the R-code Fords and the Pontiac Catalina 2+2s, for example—were gone or would be soon.

A Period of Camaro Evolution

The Camaro’s 1969 restyling continued the original look, but the 1970 model was a completely fresh design retaining not much more than the overall proportions. It continued with mild updates until 1974 brought new front and rear ends designed to meet federally mandated impact-resistance. Not everyone liked the result, as the front panel now sloped downward to an oversized bumper and the rear panel carried horizontal taillights in place of the previous round units above a similarly large bumper. The Z/28 remained available, but a look at its specifications shows that its engine was the larger 350 that somehow was rated at just 245 horsepower. That seemingly was 45 horsepower less than the Z/28’s original 302 had provided, but a direct comparison between those two V-8s is both difficult and misleading, as the 1967 engine’s output was quoted as a gross figure and beginning in 1972, a net figure was used. The former represented what the engine could produce and the latter represented what it could produce with all of its accessories in place, thus making it a lower number. Add in the early emissions equipment that was cutting into performance and the picture for all muscle cars began to look genuinely depressing.

The Camaro in all its forms struggled through that and more as it endured the gasoline-shortages, spiking insurance costs and heavy-handed regulation that ended the muscle car era, but unlike some of its competitors, it survived.

By the mid-1980s, those who’d never lost their faith in Camaros were being rewarded as 1982 brought “a whole new car—a lot of new technology.” The base engine was now a four, but the Z28 (without the slash) carried a 5.0-liter V-8 with fuel injection as an option. Those who studied specs carefully could see the future, as the carbureted version of the 305 was rated at 145 horsepower and the injected version at 165.

Horsepower, not surprisingly, didn’t play a big part in advertising, but Chevrolet wasn’t shy about mentioning the Z28’s strengths such as the 55-45 weightdistribution and “special engineering details to further reduce Camaro’s low drag coefficient… Added front and rear downforce is exerted at speed to hold Z28 to the road. Serving these aerodynamic functions: specific front facia, deep front air dam, body-side lower panels, rear air spoiler and streamlined mirrors.”

All of that was on a new body whose styling was aggressive; its only connections to the previous generation being the long-hood-short-deck, the sloping backlight and the horizontal taillights. Undoubtedly, some drivers bought 1982 Camaros purely for their looks and that was fine, but there was more. The Z28’s horsepower rose to 175 in 1983 and 190 in 1984 before reaching 230 in the new Z28 IROC of 1985.

One for the Track and Another for the Street

The IROC was Chevy’s way to mark the International Race of Champions, which used identical Camaro-based cars piloted by top drivers to ensure that each race was as close as possible to a test of pure skill. IROC had begun with Porsches in 1974 and switched to Camaros in 1975 before taking a break from 1981 through 1983. When it was revived in 1984, the Camaro was again the choice. Chevrolet decided to capitalize on that decision and advertised that it was “about to fire up IROC thunder once again.”

There was no requirement for sales of identical cars to the general public as there’d been with the original Z/28, which was a good thing since the ad delicately spoke of “skilled hands (that) have been working as purposefully as surgeons. Creating machines that have but one purpose… All specially modified Camaro Z28s.” Nobody was pretending that the competition cars and the street cars were identical.

Chevrolet gave the IROC the option of a 225-horsepower 5.7 for 1987 and stepped it up to 230 horsepower in 1988. It returned for 1989—the secondto-last year for the IROC-Z—when the 305 produced 170 horsepower with throttle-body injection and 190 when equipped with the optional Tuned Port Injection and an automatic or 220 with a five-speed manual. The feature car is a 190-horsepower version and while the additional 30 horsepower would have been nice, it was the car that Lopatofsky found and one that was too good to pass up. The Camaro was in Throop, Pennsylvania, so he drove it the half-hour to his home in Clinton Township, but not before learning some of its history

Lots of Spider Webs and Undercoating

“The car originally was sold out of Sutliff in Harrisburg, (Pennsylvania),” he said. “It was sold out of the dealership there and (the seller) had bought it from somebody down in Harrisburg… The fellow that I bought it from said the fellow in Harrisburg said it was stored and that there was nothing but spider webs underneath it. It really didn’t get driven much.”

The spider webs’ presence was a fairly convincing indicator of the condition that the Camaro had been in at the time and it had changed little by the day Lopatofsky bought it. Besides the limited driving—even today, its odometer shows only about 58,000 miles—the fact that assembly workers had been generous with the factory undercoating had certainly contributed to its survival.

“They just slopped it all over the engine bay,” he recalled. “A guy just went and sprayed it all over. It was horrendouslooking… It took me about three days to clean it out. I cleaned it out, but just in the engine bay. Back in where the decklid is, there was some in the corners there and I left it. It has the little GM (undercoating) stickers in the corners.”

Most undercoating of the era, he agreed, did its job to some degree even as it produced an unforgettable odor when new.

“It was like driving asphalt,” he laughed. “You almost smelled new pavement.”

The undercoating and the low mileage weren’t the only reasons that his Camaro had remained in such good condition. Granted that they made a big difference in Pennsylvania, where the use of road salt in winter knows few limits, but there’s strong evidence that everyone who owned the feature car before Lopatofsky took very good care of it.

“Underneath,” he said, “it still has the stickers on the back brake drums, even the little tags are on the springs in the front. Whoever had the car, it’s really, really clean. The first two owners? They were meticulous on maintenance. The spark plugs were changed twice on that car in that short length of time. The antifreeze was changed; the T-top gaskets were even changed. They went through it and spent a lot of money.”

Most of their investment went toward maintenance, but there were exceptions.

“They went and they put a threeinch exhaust on it,” Lopatofsky said, “but they kept everything else stock and they put two big pipes coming out the back, straight pipes. I took the car and I said ‘we’ve got to do something about that.’ I cut the two straight pipes and like stock, I put the turndowns on so they’d look original. The only thing is that they’re big. I painted them black so they blended in nicely.”

The owner from whom he bought it had, unfortunately, just missed out on an original feature.

“When he went and looked at the car,” Lopatofsky explained, “it still had the original Eagle GTs on it. He went back to pick the car up and said ‘what’d you do to the tires?’ He said ‘I put new ones on because I didn’t want them to blow out.’ That’s what happened so he put a set from Pep Boys on it. They’re the right size tires, but they look a little narrower.”

A 30-Year-Old Original

Driving on the original tires after a few decades wouldn’t have been especially smart, but just having them would have been a nice addition to the other pieces that have been on the Camaro since the day it left the factory. There were, for example, the build sheets that Lopatofsky and his son found just a few weeks before the car was photographed for this feature.

“I said to Kevin ‘you know, let’s look around here,’” he recalled. “We felt around under the seats and I felt a piece of paper. I said ‘get the wrenches,’ so we got the seat out and it was this sheet. Then I went on the other side. ‘There’s a piece of paper here, too. We can’t see what that is, let’s pull that seat out.’ We pulled that out, laid it out in the garage and here were two identical build sheets. They were perfect and they were in under the springs.”

The rest of the car remains almost as perfect, with no trace of the rust that’s frequently found in the quarter panels, rocker panels and the lower doors and fenders. Even the floor, Lopatofsky said, is rust-free and mechanically, the only needs have been the replacement items and maintenance that he knows are key to his plan for long-term ownership.

“I have a building, a garage at my parents’ place and that’s where they’re being stored now,” he said. “My main thing is that I keep them out of the sun as much as I can, I keep them out of the rain.”

Some Insight on Parts Shopping

All the care in the world, though, won’t offset the basic truism that cars break. Keeping nearly any Chevrolet from at least as far back as the postwar years on the road isn’t difficult since the brand’s popularity means that most mechanical parts are likely to be available. There are exceptions, though, and Lopatofsky said that finding original components for the fuel injection system can be a challenge. He said that some aftermarket replacements are available, but added that problems with the injection when the cars were in everyday use occasionally led to owners’ replacing the entire system with a new manifold and a carburetor, which helps to explain the relative rarity of the original parts.

“That’s one of the things I’ve got my eyes on when I’m out there looking around,” he said. “If I see some of that stuff, it’s going to come home.”

Trim pieces are in good supply, he said, and while he generally doesn’t acquire parts just to build a stockpile, he does watch for some specific items.

“If I find something that I know I’m going to need down the road,” he said, “then yeah, I’ll grab it, but fenders and doors and stuff like that? I figure I can keep what I’ve got on there as long as I can maintain it. If I get in an accident or something happens, well, then it becomes an issue, but where do I store all of this stuff?”

The Camaro’s Next Owner Is…

Beyond its overall condition and the likelihood that it won’t need serious work for years and years, the IROC’s future is secure.

“My daughter wants the IROC,” Lopatofsky said.

It’s going to be waiting for her because Lopatofsky’s wife, Louise, likes the Camaro just as much as their daughter likes it.

“She likes the IROC,” he explained. “I said ‘I’m going to get rid of that IROC. I’m going to get rid of it and trade it.’ ‘No, no, no, no, no.’”

“I always give him that look,” Louise said.

“I get the look,” Frank admitted, “and I know what the look means.”