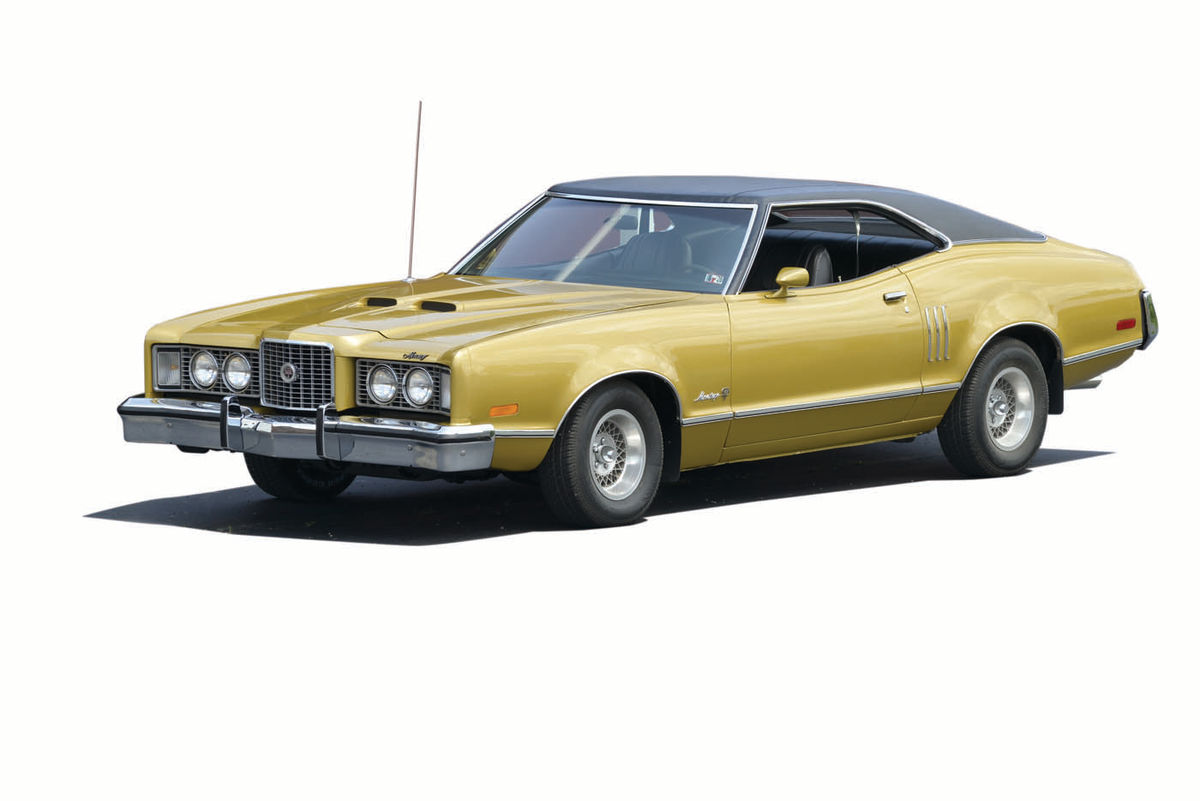

1973 Mercury Montego GT

He Bought This Uncommon Car New and Intends to Keep It In the Family…Even If a Steering wheel or Badge Can Cost $400.

If Roger Jayne ever were to question his decision to buy a 1973 Mercury Montego GT, he probably would’ve done so by now.

“I bought it in 1973,” he said, “ordered it in. I was looking at the flier like they have in all car dealerships. I saw a picture of it and I said ‘hey, that’s a nice-looking car’ and I just decided to go with the Mercury.”

Jayne was a Mopar fan at the time—his first car had been a 1958 Chrysler— and he remains one today, but the Montego’s looks caught his attention. It was probably much the same with the launch of the Mercury brand in 1939, when advertising introduced “the newest member of the Ford-Lincoln family” with the promise that “you’ll want a Mercury. Its long, sleek lines are wing-like in the wind…its interior, an ensemble of smart upholstery and accessories.”

It Played a Key Corporate Role

While all the studying and predicting in the world of 1939 couldn’t possibly have guaranteed that the Mercury had a future, it was both a gamble and a smart move on Ford’s part to launch this new car. The risk was choosing to do so even as other badges had been disappearing for years; the wisdom was in the fact that the Mercury could fill a slot above the Ford and below the Lincoln.

It all paid off and the Mercury returned for 1940, again looking very much like a slightly larger Ford. Advertising made the point that it was not small, boasting that “in size, in roominess, in power, in comfort and luxury, the Mercury is everything a big, fine car should be.” But with the Great Depression still fresh in the public’s mind, it added that “owners report up to 20 miles per gallon of gas!”

Restyled for 1941, the Mercury was on its way to success, although its streak was interrupted when World War II’s onset brought an early end to the 1942 model year for all automakers.

When the war ended in 1945, the 1946 Mercurys, like their competitors, were not much more than re-trimmed 1942s. That was fine in the sellers’ market then thriving, but everyone knew that conditions would have to return to normal and gradually, truly modern postwar designs began to appear.

Mercury’s New, Post-War Style

At Ford, 1949 brought the new models and when that happened, the Mercury lost nearly all of its visual ties to Ford and instead seemed much more like a Lincoln. Smooth and pleasantly bulky, it was “mighty good-looking,” according to advertising. Ads spoke of the new engine, still a flathead V-8 and now producing 110 horsepower from 255 cubic inches, but that lost some of its importance thanks to the genuinely new overhead-valve V-8s introduced that year by Cadillac and Oldsmobile.

The industry was quick to follow GM’s engine lead beginning with Studebaker and Chrysler in 1951, and Mercury’s turn came in 1954. The result was worth the effort, as the new 256-cubic-inch V-8 produced 161 horsepower, a major jump from the previous 125-horsepower 255.

Although nailing down the precise start of the horsepower race is effectively impossible, it’s safe to say that it began in the mid-1950s and Mercury was ready. For 1956, it announced “the big, powerful 225-horsepower SafetySurge V-8—a new engine that will take you flashing along the highway, soaring up steep grades or just loafing through traffic easily and smoothly. Endurance tests proved this V-8 capable of taking more punishment than you would normally ever give it. Acceleration tests showed Mercury’s ‘take-off’ is faster than ever before. Gasoline consumption tests found that this V-8 can add still more honors to Mercury’s long history of economy. Most important, this new V-8 offers you more usable power—not just for high speeds, but for 99 percent of your driving.”

The ad copy concluded with the note that “Mercury’s new SafetySurge V-8 engine is also available in a 210-horsepower version.” Each displaced 312 cubic inches and even the lesser version represented an impressive improvement from just two years earlier.

In 1957, buyers had the option of “the magnificent Turnpike Cruiser engine with 290 horsepower, 368-cubic-inch displacement, 9.75-to-1 compression ratio…the mightiest engine ever offered in a Mercury.”

Performance was becoming a major focus among the Big Three and the remaining Independents, so it was no surprise to read that “for those who insist upon the ultimate in fine-car performance, Mercury offers the 400-horsepower Super Marauder. You’ve never enjoyed a more willing V-8—430 cubic-inch displacement, 10.5-to-1 compression ratio. Whatever the driving situation, this engine answers your every command…this quiet, efficient Super Marauder sets a new standard of engine performance.”

A Movement Toward More Variety…

Everything might have continued on that all-out performance course were it not for the compacts that were about to appear in showrooms alongside of full-size American cars.

American drivers had been barely interested in smaller cars until the 1950s when Volkswagen made a carefully thought-out entry into the United States and proved that owners of foreign cars could rely on a strong dealer network. Other imports were arriving and some were succeeding, all of which inspired American automakers to take compacts seriously and 1960 brought the first group of those smaller cars from the Big Three.

Chevrolet’s Corvair was unconventional with its rear-mounted air-cooled six, but Chrysler’s Valiant was a typical American car in everything but size. The same was true for Ford’s Falcon and its Mercury sibling, the Comet. Advertising boasted that the Comet “looks like a million, runs on pennies, turns on a dime… The new Thrift Power Six delivers up to 28 miles per gallon of regular gas.”

More than 116,000 Comets were sold in the first model year, guaranteeing its return, but Mercury’s lineup was about to grow somewhat complicated as 1961 brought the Meteor, “a new and better kind of low-price car.”

Its 120-inch wheelbase made the Meteor a full-size car six inches longer than the Comet and “a full-fledged Mercury in every respect.” Mercury had long positioned itself as an affordable fine car and while the Meteor was available with a six and “priced to compete with the low-price field,” it offered “extra quality in the coachwork, extra luxury in the fabrics, extra room inside, extra value everywhere.”

The Meteor took a different turn in 1962, though, when it became “the newsize car that fills the gap between big cars and compacts.” Now on a 116.5-inch wheelbase, it was “priced like a compact (with) luxuries of a big car” and “saves like a compact…performs like a big car.”

Like the Comet, it had a close relative at Ford, in this case the Fairlane, but whether consciously or otherwise, buried in a Meteor ad was a look at the future. “Either Mercury Meteor ‘6’ or Meteor 221 V-8,” the copy explained, “produces pennypinching, economy-car mileage along with a frisky performance level due to beautiful balance between power and weight (Meteor weighs under 3000 pounds), which means brilliant Meteor performance for hills and passing.” In other words, the Meteor could be ordered with an engine bigger than necessary and there’s really only one reason to do that. Those who hadn’t grasped it were told that “this shortstroke, high-efficiency power plant… gives you that extra ‘go’ on regular gas.”

The slightly updated 1963 Meteor went further, “especially if you choose the exciting new, optional Lightning 260 V-8 engine.” The 145-horsepower 221 remained available, but the new engine’s 164 horsepower provided another look at the future even if that future lacked a place for the Meteor. Instead, the compact Comet received some attention in the form of the 289 V-8 with its 210 horsepower.

At that point, it becomes clear that the intermediate Montego’s ancestry doesn’t flow in a perfectly straight line, as Mercury explained that the “Comet owns a bigger piece of the road for 1966. It’s sleeker. Roomier. Longer. Up to eight inches longer. And with muscles to match. Big, powerful engines, up to a new 390 four-barrel that specializes in getaway.” The brochure waited until the specifications page to state that the 390 was producing 335 horsepower.

The Cougar followed in 1967 as Mercury’s upscale interpretation of the Mustang, but the intermediate Comet wasn’t shoved aside and to prove it, a 425-horsepower 427 became an option for those drivers who felt that the 390 just didn’t cut it.

Introducing a Cross Between the Comet and Cougar

When 1968 brought a completely restyled Comet, the line included a new name, Montego. The Cyclone continued as the Comet aimed at the performance-minded while the Montego was “a car that looks, feels and rides like the fine car it is” and “combines Cougar excitement with full six-passenger comfort.” The “Cougar excitement” would undoubtedly be intensified if the standard 115-horsepower 200 six were replaced with the optional 325-horsepower 390. Those who took their time in making a decision were rewarded in 1969, when the 335-horsepower 428 became available.

Time for an “All-New” Montego

By 1971, the Comet had become a rebadged Ford Maverick, leaving the Cyclone and Montego as the intermediate performance cars, but one year later, ads announced the “all-new Mercury Montego GT… No facelift. New. From the tires up. It rides on a new highstability suspension designed to give you quick, responsive handling with a sure, smooth ride… What else is new? Standard engine: 302 V-8. Options up to a 429 four-barrel.”

However, the world was changing for performance cars as their continued existence seemed unlikely in the face of increasing insurance premiums and growing governmental regulations. They took a psychological hit, too, as manufacturers began stating horsepower in net rather than gross figures for 1972. The new system was more accurate, as it was obtained by measuring an engine’s output with all accessories in place and operating, but the resulting number was now lower, since gross horsepower measurements had been obtained from an engine running with no accessories.

Still, high-performance cars didn’t instantly vanish and at Mercury, the Montego GT returned in 1973 with necessary changes, the most obvious of which was the addition of the required impact bumper. Designed to withstand a low-speed impact with no damage, it worked as planned on every manufacturer’s models, but no one was pleased with the look or the added weight.

Drawn to This Car

The ’73 Montego GT wasn’t significantly changed from its 1972 design and to Mercury’s credit, the oversized front bumper didn’t seem as out-of-place as did some of the competition’s. In fact, not everybody saw it as ruining the car’s appearance and as mentioned above, Roger Jayne liked the Montego’s look. There was, however, more to it.

“I wanted a big engine,” he recalled. “I wanted a 429, but you had to get the automatic transmission. You couldn’t get a four-speed with it. I guess I’d really rather have a four-speed. I’m glad I did.”

What he did get in his four-speed car was the 351 Cleveland with its 159 horsepower and the proof that his choice was the right one soon followed, as he would generally park the Montego during the winter to protect it from the harsh winters—and salt-covered roads— typical in the area around his Laceyville, Pennsylvania, home. That would keep it looking good and not long after he bought it, he and his future wife began dating in it. Her parents, Jeannie recalled, didn’t feel a need to warn her about guys who drove such cars.

“My older sister,” she explained, “her boyfriend had Mach 1s.”

While she admitted that she “probably” liked Roger’s three-quarter-ton fourwheel-drive Ford pickup more, it was the Montego on which she learned about manual transmissions. No doubt there were better vehicles on which to start.

“When I bought that car at Vitale’s in Montrose (Pennsylvania),” Roger laughed, “they pulled it up to the door and I got in it. I could not get it into reverse. You have to slap it way over to get it into reverse. I had to have a salesman come out and show me how to get it into reverse. Boy, did I feel stupid.”

Tricky shifter or not, both soon became comfortable with the Montego.

“We met in January and we were engaged by the end of May,” Jeannie said, “and at that point, I was driving the car. There’d be times when we’d be out on a date and he’d be tired. He’d say ‘just take the car home.’ And then that fall was the first fall I worked here (on Roger’s family’s farm), so he let me drive it back and forth. I grew up just outside of Sylvara (Pennsylvania), so it wasn’t like it was really far.”

The Montego then took them on their honeymoon and served as the everyday vehicle when the pickup wasn’t being used. It also went on vacation trips, a role that revealed a problem.

“We had a daughter who at a very, very young age, hated heat, so we bought an air-conditioned minivan,” Jeannie said.

“Yeah, (the Montego has) no air conditioning, black vinyl seats, black vinyl roof,” Roger added. “Changing a diaper in the backseat wasn’t any fun.”

Sell It Or Restore It?

By about 1988, even the good-weather use was mostly finished and the car was parked in a machine shed. As storage goes, the shed was a better choice than it might seem to be, as it had a solid floor, sat on a knoll with good drainage and was closed, but not sealed so tightly that air couldn’t circulate. Roger said he also drove the Montego occasionally for several years, but not far because it had developed a cracked exhaust manifold. The heater core then began leaking badly and once that was repaired, he found that it had damaged the floor. Finally, it was off the road and he recalled that he had a serious offer from a potential buyer, but turned it down.

“I knew he’d go out and kill himself in it,” he explained.

“We didn’t want to see it,” Jeannie said.

“If we were going to sell it, we were going to sell it far enough away so that we wouldn’t have to see it.”

Then, about a decade ago, they began thinking about a restoration, but even in its fairly good shed, the car had deteriorated.

“The rear wheelwell has chrome around it,” Roger said, “and the chrome was about ready to fall off because there was nothing to hook it to. The passenger’s floor was rotted out, (but) the paint still sparkled and shone nice. The chrome on the bumpers was all peeling off, the rear bumper, especially.”

It hadn’t reached the point of looking so bad that it would stand out on the road, but finances now made the idea of restoring it realistic. A decision, though, depended on several factors besides affordability, namely the lack of time due to the demands of operating a farm and the necessity to learn many of the skills that the work would require. A friend solved that when he recommended a shop that would handle the work.

“He was doing other cars at the same time, AMCs, Javelins,” Roger said. “That’s what he has and restores for himself, so when he saw this Mercury, I didn’t know whether he’d be interested in doing it.”

“He’d never seen one,” Jeannie interjected.

Still, he accepted the job and about five or six years ago, the work began. While the Montego was apart, the engine was rebuilt to stock specifications and Roger said that at 65,000 miles, it was giving no indication of problems beyond that cracked manifold, but since it was out of the car, a rebuild was the safe approach.

Some Cost Drawbacks With an Uncommon Car

It’s almost impossible to imagine an essential mechanical part of any American car built since World War II that would be difficult or prohibitively expensive to find, but sheet metal, trim and interior components for an unusual model—like a Montego GT—might be a different matter.

“The steering wheel’s got three cracks in it,” Jeannie said, “but it’s got the horn that’s inside the rim and I think (the shop) said that was going to be like $400, $500, $600. ‘No, we can drive it the way it is.’ It’s like why we didn’t go ahead, but at the point, we’ve got enough money in the car.”

“I don’t mind paying for something that’s worth it,” Roger said, “but when somebody has something like the ‘GT’ on the front grille; somebody had that on eBay for $400 or $600. I was like ‘I don’t care. I’m just not going to give you that much money for that.’”

It’s Certainly Not Modern… But It Has Family History

By 2017, the project was complete and the Montego was back. The first ride was less than 10 miles and the differences from modern cars showed up quickly.

“We decided,” Roger said, “the newer cars are a lot easier-riding than that, quieter and everything… Cars have advanced so much now that even my pickup truck rides so much smoother and nicer. But we’re glad we did it and we’re happy with it.”

“If he hadn’t bought it new,” Jeannie said, “if it didn’t have our history, then we probably would never have done it.”

Although the Montego might seem to fly under the radar—it lacks the stripes and graphics often seen on performance cars of the day—that hasn’t always translated to blending into the crowd. Jeannie recalled an experience at a rest area on the Schuylkill Expressway near Philadelphia around 1980.

“I pulled into where the trucks were supposed to be,” she said, “and some guy came running. Roger said ‘he’s going to yell at you for parking in the wrong place.’ He didn’t want to yell at me. He wanted to trade cars. He wanted our car.

“And there was one time when I was in Montrose,” Jeannie added, “when it was still the family car. I was coming through South Montrose, where there was an active garage and this kid came running out of the garage, ‘I love your car.’”

She said that it’s noticed today and often mistaken for a Torino, but gave the example of what can happen while at a gas stop.

“When they see us pull out the license plate to get to the gas filler,” she said, “that would probably make them look twice.”

“It’s different enough,” Roger said. “It’s got round headlights.”

“I think people kind of notice the front’s presence,” Jeannie said, “the long hood.”

The demands on the Jaynes’ time didn’t let up once the car’s restoration was complete and the Montego doesn’t get out a lot. It does, however, still require attention even though it was at first carefully stored in an addition to one of the farm’s buildings.

“One day,” Roger said, “I went out there and just ran my hand under the rocker panel and it was dripping wet.”

“That’s when I told him ‘we’re going to take my car out of the garage because it has the wood floor and in the winter, it’s got the wood stove,’” Jeannie said. “‘That’s where it’s got to be stored.’ It’s like a job now, so I’ve decided that one vehicle’s enough to have to take care of and worry about the mice and everything else.”