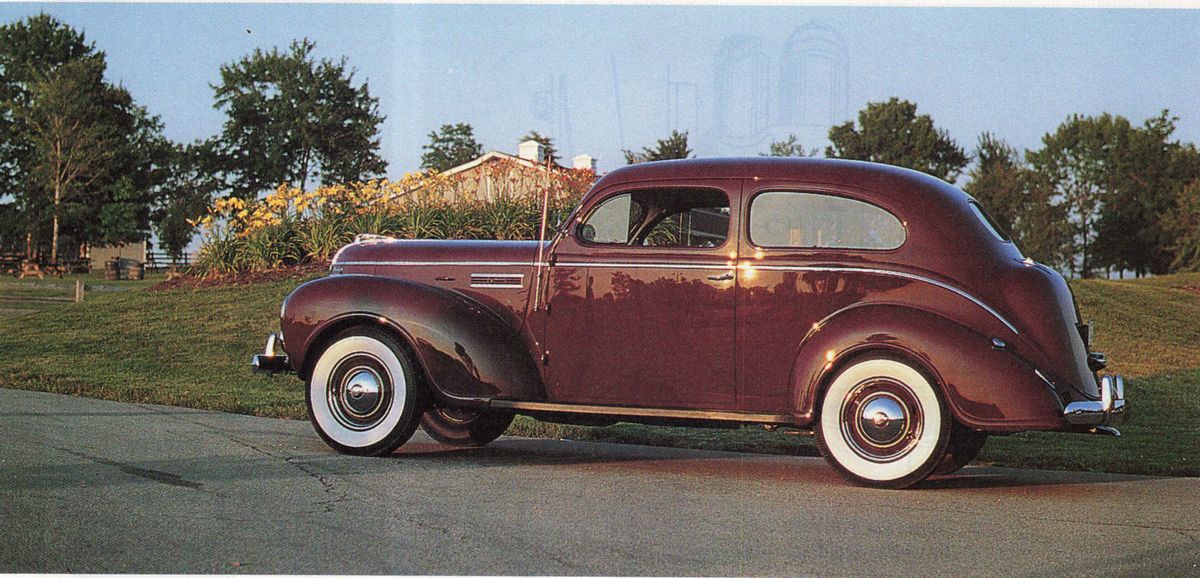

1939 Plymouth P-7 Roadking

Not every old car found in a Ne is pristine. This 1939 Plymouth P-7 Roadking was carefully stored in 1956 and remained in nice condition for many years. Then in ’69 a tornado ripped the roof off the barn and the old Plymouth fell victim to whatever came through the hole — including parts of the roof itself.

More years passed, and the car started to settle through the floor of the barn. During a 1986 visit to the family friends who owned the Plymouth, John Zinkand noticed it was almost down to its frame. He asked if he could buy the car and restore it, and they gave it to him. Another friend helped him winch it out of the barn and tow it home.

Years of weather had taken their toll. The body was so rusty that Zinkand pulled off the rear fenders without removing any bolts. Holes had rusted through the roof, ruining the interior, and the doors were rusted shut. Zinkand says, “I was told to junk it; just use the engine and chassis and get a different body, but I wanted to fix it.”

Zinkand, a marine mechanic by trade, had never restored a car before. The Plymouth sat in his backyard for a year while he did some research. His biggest worry was parts availability. He found it wouldn’t be hard to get parts for anything except the body. There are several companies devoted to making and selling Plymouth parts, and strong national clubs provide technical advice and camaraderie (see Resources).

The restoration started seriously in 1987. After tinkering with the motor (a compression check showed the valves were stuck and he tapped on them to free them up), Zinkand got the engine running and drove the car from the back yard to the front. He then took the body off and put it in the garage, parking the chassis under a tarp in the driveway.

“I never did bodywork before,” Zinkand says. “The part that I dreaded I did first. I figured if I tackled the body and I was able to do that, the rest was gonna be easy.”

Beat and Heat

“Where the fenders attach to the body, it was completely gone. The car actually pulled apart it was so rotten,” Zinkand says. “I bought sheetmetal and formed my own pieces. The rockers, lower body panels, the panel below the trunk, rain gutters, patches for the roof and fenders: I had to make all that stuff. This car taught me a lot.” The sheetmetal was hand-shaped over wooden forms. Due to the deteriorated condition of the sheetmetal, some guesswork was involved in the fabrication of these forms. He started with what remained of a panel and used cardboard to form a template of what he assumed was the shape of the missing portions. Zinkand glued 4x4s together and ground them to the correct curves. He beat the sheetmetal over these forms using a mallet and a dolly. He says, “I tried to get the sheetmetal as close as I could and used very little body filler. Most of it was trial and error. If I got it wrong, I did it again. I found I was better off working a little of the metal at a time because it’s hard to get the curve out of sheetmetal once you've formed it.”

Welding was another area where Zinkand had little experience. He gas welded and brazed the patches in place. The best technique he found was to tack weld the patches to hold them, then weld the seam completely. When possible, he weld ed both the inside and outside of the seam to keep moisture out.

Warpage was a problem during welding. A friend who works in a body shop taught him how to heat shrink the metal back to its original shape. As Zinkand explains it, “If you have a bulge or indentation you can’t pull out, heat it red hot with your torch and quench it with water and it will shrink back. You'll end up with a small dimple which you can tap back with a hammer and a dolly.”

More than two years passed before the body could be prepared for painting. Zinkand says good primers were important during this phase of the restoration. He recommends two-part epoxy primers as the base, even though they’re expensive, because they are good at resisting rust and moisture.

To cover the epoxy, Zinkand used different colors of filling and finishing primers. He block sanded by hand, and whenever he rubbed through one layer and exposed a different color of primer he knew he had a high spot to deal with. If it was a high bump, he hit it with a body hammer. If it was just a little rise in the metal, he built up the area around it with primer.

For paint, Zinkand chose acrylic lacquer instead of urethane or enamel paints. He’d read that lacquer was more forgiving of dust and other imperfections because it’s easier to sand out. Since he was doing the paint job in his own garage instead of a professional paint booth, this was a concern. The quality results reflect the extreme care Zinkand took in priming and painting.

“ld put a couple of coats on and sand them out. If everything went well on a particular piece, ’'d put on the finishing coat and wet sand,” Zinkand says. “I didn’t wet sand between every coat because I didn’t think it was necessary. Finally, I put on a clear coat to keep the shine longer.” He painted the car piece by piece, but took a week off from work so the temperature and humidity would be similar for each portion of the job.

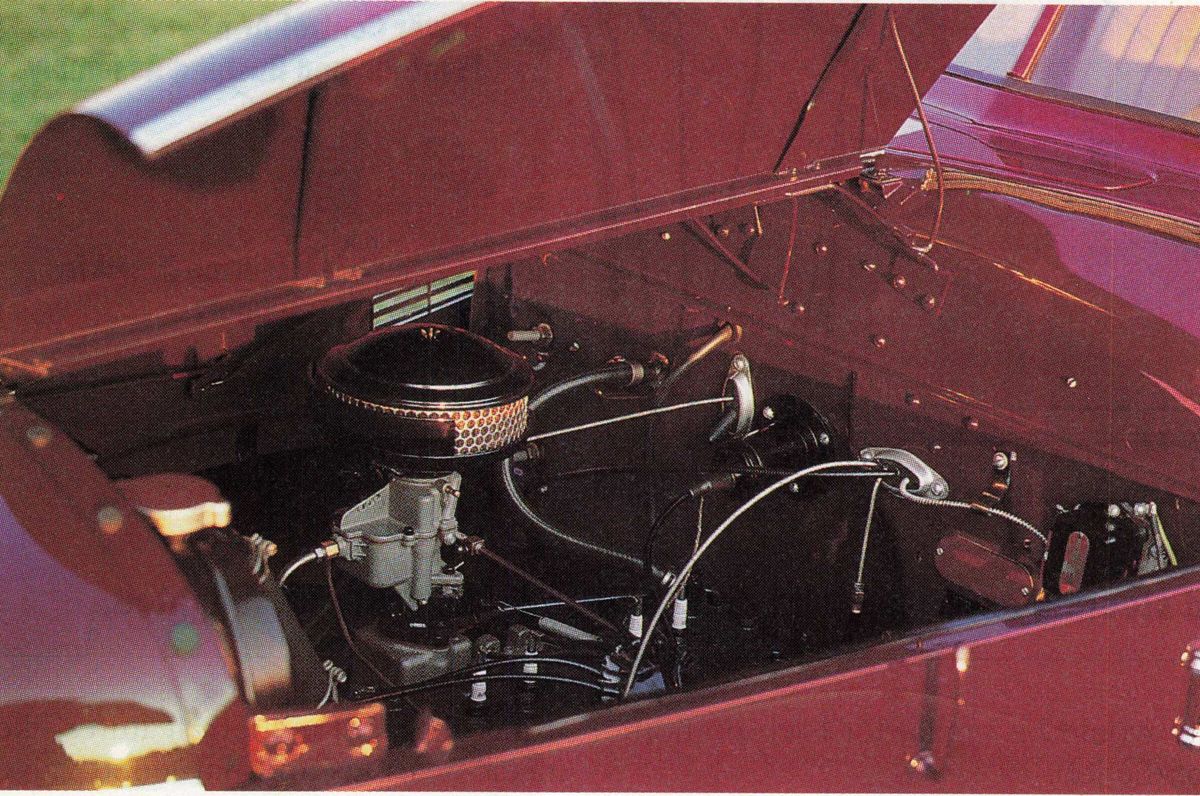

Mechanical Marvel

With the body shaping up, it was time to tackle the powertrain and chassis. There were some pleasant surprises here. Despite about 58,000 miles. of use, there weren’t any ridges at the tops of the engine’s cylinders. And before the car had been stored in °56, the owner had changed the oil and antifreeze, which did much to preserve the old flathead. Zinkand says that rebuilding the motor was fairly easy.

Plymouth’s side-valve six was built with minor revisions from 1933 through 1959, so parts are easy to find through Plymouth parts sources. It incorporated modern features like insert bearings and hardened valve seats. The latter, a long-time feature of Mopars, made grinding the valves a chore, but also meant Zinkand’s car can run on unleaded without modification.

The pistons were Zinkand’s only parts problem. His car didn’t need oversize pistons, but the top ring grooves were worn and sloppy. A new set of pistons would have cost about $240, and since the car would be driven less than 2000 miles annually after its restoration, Zinkand decided repairs rather than replacement would give him adequate performance and reliability. He found a machinist who knurled the pistons for him and installed spacers to take the slop out of the rings.

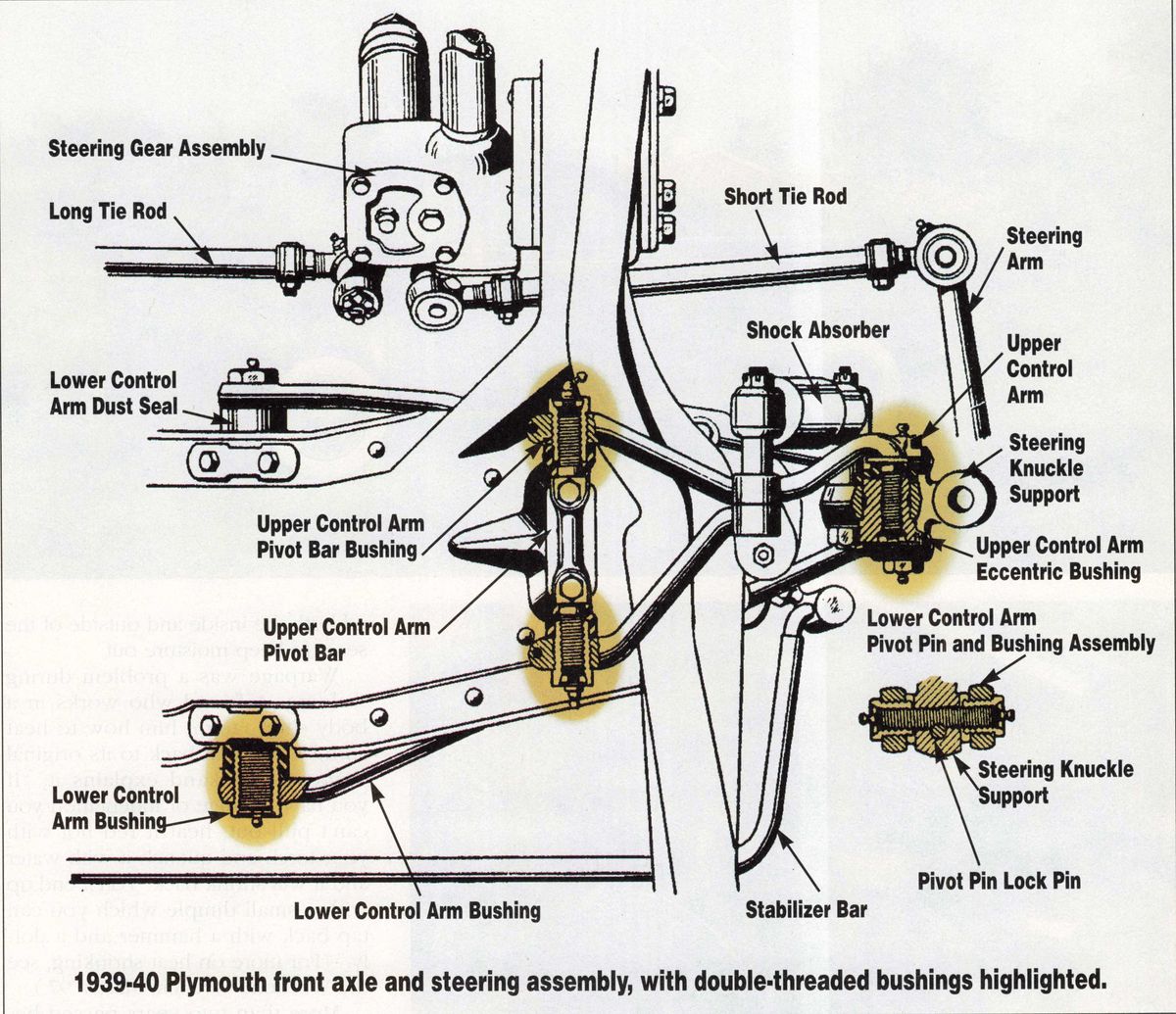

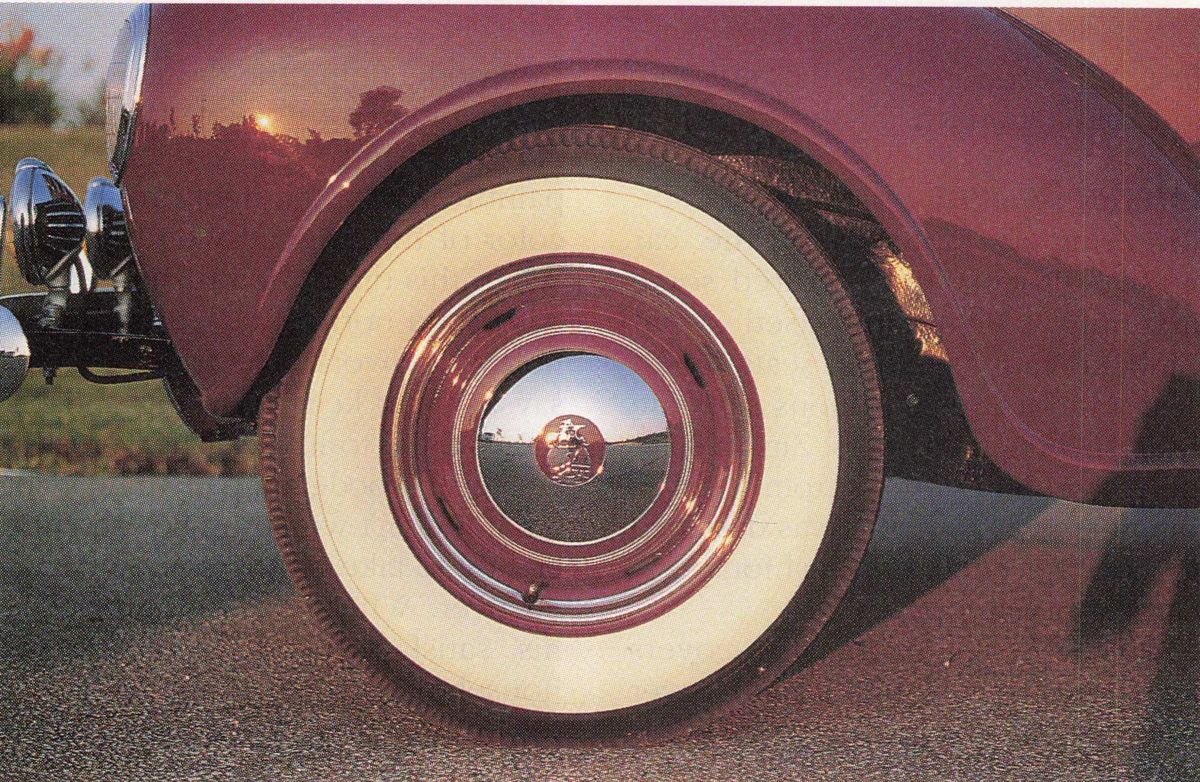

The front suspension was more of a challenge. Plymouth had briefly introduced independent front suspension on 1934 models, then returned to solid axles until 1939. The 1939 Plymouth used A-arms, coil springs and kingpins, but the bushings were unlike anything Zinkand had seen before.

Instead of rubber, the joints ride in steel bushings that need to be constantly greased because they rotate and slide in their housings and on the A-arms. Zinkand couldn’t disassemble them until he got a parts manual and realized the bushings double-threaded onto the inside part and into the outside part at the same time. “Actually,” Zinkand says, “it was fun doing this because it was so different from anything I’d seen before. Just looking at them you’d never figure out how they came apart.”

The floor-shifted three-speed transmission was troublesome. Zinkand disassembled it and inspected every item for wear or damage. When the transmission was reassembled, there was a little - grinding noise going into second _ while the transmission was cold. He took it apart again and replaced some undersized thrust washers, but the problem persisted.

Other Plymouth buffs told Zinkand slow first-to-second synchros were a common problem that he wouldn't be able to solve. After experimenting with different gear oils, he found 130-weight racing oil helps the problem somewhat. Still, pausing a second or two between first and second gear is the best way to avoid a graunch.

Interior Designs

Restoring the interior of the car wasn't difficult, but required some ingenuity. Plymouth used what Zinkand calls “skeleton seats,” with seat and backrest cushions separate from sheetmetal carriers. Zinkand ordered an upholstery kit from Walston Interiors, only to find it was designed to go over both the cushions and Carriers in one piece.

His wife Vinette cut the covers apart and sewed them to go over each part separately, as originally designed. She also stitched new armrests and door panels, using material from Walston and patterns from the original, moldy upholstery. She did most of the work on a sewing machine, but some of the corners had to be done by hand.

Zinkand says all the instrument panel knobs were in good condition. The fuel gauge needed to be replaced because even after he had worked on it, it still was unreliable. The other gauges were restored with the help of a friend who silkscreened new faces onto them. The safety-signal speedometer, which cast green, yellow or red light on the speedometer face depending on speed, was in fine shape.

Woodgraining the dash was similar to antiquing woodwork, according to Zinkand. He mixed automotive paint to match the light brown base color of the original woodgraining. When this dried, he brushed on oil base stain normally used on household woodwork. The trick, Zinkand says, was to keep brushing until the stain started to harden, then brush in whatever woodgrain pattern he wanted. If it didn’t work out, he used mineral oil to take off the stain and started over. When everything dried to his satisfaction, Zinkand sprayed household polyurethane clearcoat (not automotive paint) to protect it. Automotive paint would have acted as a solvent for the oil base stain and caused it to lift from the dash.

Bumper Roulette

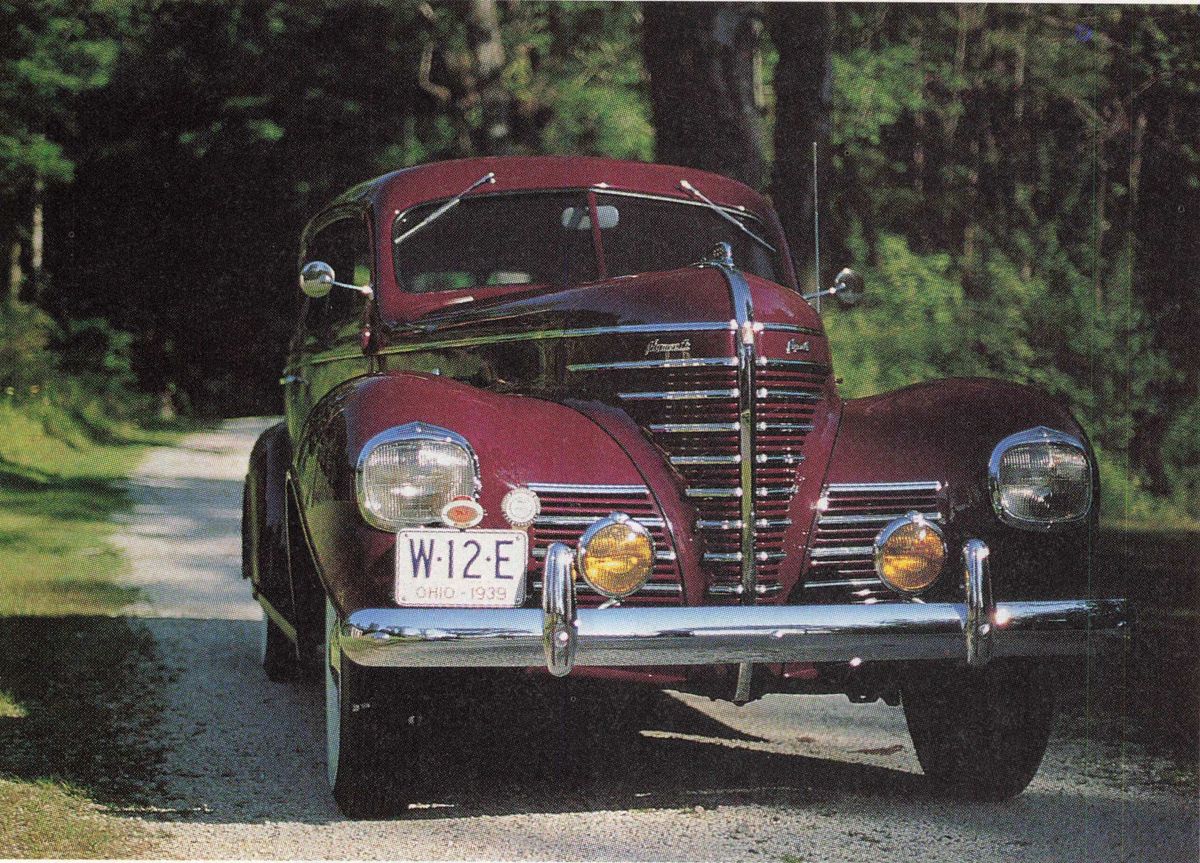

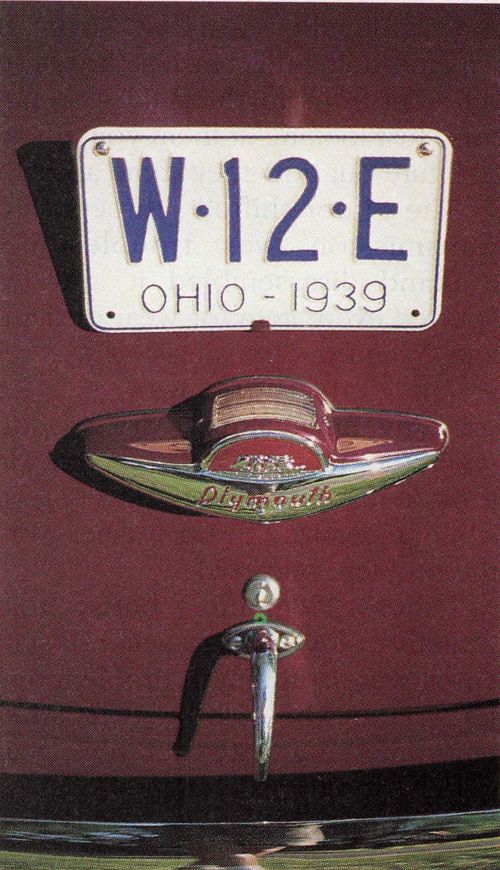

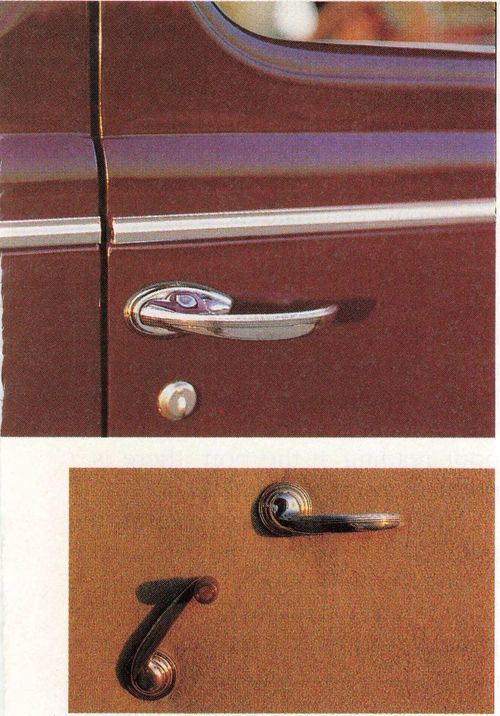

Probably the single most frustrating item of the restoration for Zinkand was trying to find good trim and good chrome-platers. Although the '39 Plymouth shared its basic body with the ’37 and ’38 models, an extensively restyled front end gave it an up-to-date prow that presaged the redesigned ’40 Plymouth. Thus, the P-7 Roadking and P-8 Deluxe models built in 1939 share very little trim or body parts with other years. The hood ornament and bumper guards, for instance, are the only pieces shared with the 1940 Plymouth.

The rectangular headlights unique to 1939 are an interesting styling feature. They anticipated the industrywide adoption of sealed beam headlights in 1940, but behind the lenses are old-fashioned bulbs and reflectors. The lens and chrome frame are hard to find. Zinkand started with a decent set and lucked into another set at a swap meet for $15.

Bumpers posed a particular problem. Zinkand’s were solid but needed to be re-chromed. A local shop offered a lifetime warranty, but did such a poor job that Zinkand returned the bumpers seven times before giving up in disgust.

The shop made several errors, according to Zinkand. They didn’t copper-plate the bumpers before chroming them, so the chrome would eventually flake off. And instead of using the bolt holes to mount the bumpers, they welded washers to the back. The heat from welding would cause the spring steel bumpers to crack, and then the shop would chrome right over the cracks.

Eventually, Zinkand met a representative of Qual Krom at Carlisle and decided to try their services. This time, the bumpers came back flawless, and the cracks have never resurfaced. Zinkand says, “As far as I’m concerned, they’re great. When you take your stuff in there they photograph everything, so nothing gets lost. When I got my bumpers back you couldn’t even tell where they were fixed, it was that good.”

Family Matters Since the restoration was completed a few years ago, the Roadking has earned several AACA _ awards. Zinkand, his wife and daughter enjoy driving and showing the classic Plymouth sedan.

Twelve-year-old Christie grew up with the car, spending her infancy playing in the garage while dad worked on the Plymouth. Zinkand says, “She’s right there with me at car shows; she likes going to meet a lot of people. She helps me clean it before and after shows. This is something the whole family enjoys.”

Zinkand doesn’t regret the time and effort spent restoring the Plymouth. He only wishes the friends who stored the car and then gave it to him could have lived long enough to see the restoration completed. Their once-treasured Roadking has come a long way from that decrepit wreck decomposing in a neglected barn.