How -to Inspecting a Prospective Project, Pt. 1

Making a Good Choice Calls for a Mixture of Emotion & Logic. This Will Help You Get Started In Your Search.

YEARS AGO I came across a 1940 Packard 110 Business coupe and fell in love with it. I have always been a sucker for 1930s and ’40s era coupes with their sensuous lines and long elegant hoods.

I glanced over the car, drove it around the block, and arrived at a price. I had no idea what the car actually was worth, nor did I know what it would cost to restore it. I just wanted it.

As it turned out, I got lucky. The car actually was in good restorable condition and parts weren’t that hard to find for it. I did most of the work myself, but I still wound up spending quite a bit more on the restoration than the car was worth. I did it right, though, and 25 years later it still bags trophies. In addition, it’s now worth more than I have in it, but had I put that money in real estate, stocks or bonds I might have done better. On the other hand, I might have lost those types of investments in the recession.

I still take my Packard out for Sunday drives and enjoy every minute of the experience…perhaps even more than I did when I first restored it. So when I talk about the economic ramifications of restoration, please keep in mind that it is all relative to your goals and desires, and how long you plan to keep the car.

Pitfalls I Luckily Avoided

I could have made a huge mistake if that Packard had major rust in it or extensive, poorly done body repairs, or had the wrong engine or driveline.

I was hasty, but I got lucky, because there are cars that just should not be restored for one reason or another. For example, some fairly common cars are so badly rusted that restoring them would cost a fortune in time and money, and would still not produce an original car in correct condition. And other cars are survivors in outstanding original condition. Restoring them would just compromise their authenticity.

Reasons to Restore

Almost any old car can be restored; it comes down to how much you love it, and how much time and money you are willing to spend doing the job. I use the term “spend” rather than “invest,” because unless you are astute, experienced, or lucky you are not likely to profit from your endeavors in the short run. The truth is, it usually makes little economic sense to restore an old production car at all if you can buy a good example already done for less than it will cost you to restore a derelict.

So why restore at all? Well, I can think of several reasons:

1. Just as I do, you might actually enjoy the process of making old cars new again and saving them from the crusher, whether doing so makes economic sense or not.

2. Your prospective restoration candidate is the car you always wanted; or perhaps even the very car your dad had when you were a kid, so it has huge sentimental value

3. Or perhaps you want your automotive object of affection to be exactly the way you would have ordered it from the factory in the old days; or you want it modified in certain ways to make it more roadworthy today.

4. It could also be that in a barn in the middle of nowhere you’ve found the long lost Ferrari that Juan Fangio drove to the championship in 1953. And if that is the case, and you are sensible about what you pay for it, you could make money restoring such a masterpiece. But that is sort of like finding a Rembrandt at a garage sale.

So, Which Cars Do You Restore?

As a general rule, the more desirable a car is, the more it will pay you to restore it. That advice may seem obvious, but did you notice that I said “desirable;” I didn’t say “rare?”

Cars are often rare for a reason. One might be that they were unpopular to begin with, so nobody bought them in their era, which usually means that not many people want them today either. An example would be the Studebaker Scotsman from the late 1950s.

It was frumpy looking, with painted hubcaps, and it was Spartan and underpowered with its outdated little flathead six. Yes, I have seen them restored, and bless the people who have done so, because it allows the rest of us to see a unique bit of history. Besides, the Scotsman was a reliable well-built car that could be fun to drive. But if your restoration efforts went much beyond a tune-up and an oil change you would most likely be upside-down or as they say now, “underwater” in the car financially.

Another reason a car might be rare is because it was mechanically marginal; it didn’t last. I cite as an example the Renault Dauphine of the early ’60s. They were unreliable, rust prone and inadequate for American roads. I know; I worked on them. Would I like to see one restored? Sure. They, too, were a part of our automotive heritage. Would I accept one if it were given to me? Well, let’s just say there are a number of other cars I would prefer to see in my garage.

Popular Then Means Popular Now

The classics most in demand; ones that bring the highest prices at auction are the ones that were popular and sought after when they were built. That’s why today, mid-’60s Mustangs and mid-’50s Chevrolets bring numerous bids at the auctions. And that’s why nearly everything is still made for these cars. People loved them then, and they love them now. Other cars that fetch the attention are the muscle cars of the ’60s and early ’70s and the great classics of the early 1930s.

At the top of the list for any of the sought-after makes are convertibles, while at the bottom are four-door sedans. Because of this, sadly, not enough four door sedans are being restored, even though they make wonderful touring cars. Aside from not being as glamorous and handsome as the open cars and coupes as a rule, four-door sedans are expensive to restore cosmetically. They require more paint, more work, and their interiors are more expensive to replicate. (For a look at a four-door sedan that has been restored, see the February issue.)

Things You’ll Need

• Magnet

• Tarp or ground sheet

• Small notebook and pencil

• Digital camera

• Flashlight

• Small mirror

• Hawkeye Borescope (Optional)

Let’s Get Started With Our Search

If you are a first-time restorer, join the club for your marque, and use club and other types of literature to familiarize yourself with the car you are considering. If possible, take an expert with you when you inspect your potential project vehicle. Most clubs have technical advisors who may be willing to accompany you if you are willing to buy them lunch. Or take a good panel beater or mechanic along to help you with the evaluation.

Rust is by far the worst problem you will have to deal with in any restoration. Extensive rust damage makes all but the most valuable and sought-after cars not worth restoring even for one’s own use. Mechanical work is comparatively inexpensive by comparison.

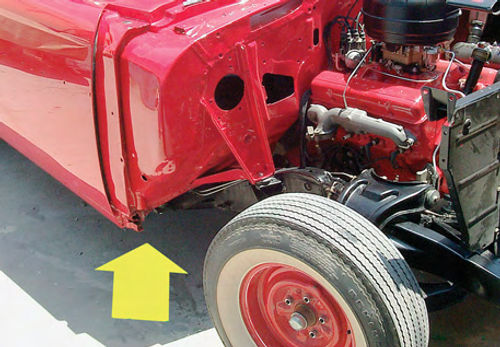

So start your evaluation by inspecting around kick panels, rocker panels, drip moldings, interior floors and under mats in the trunk as well as lower trunk lids and surrounds for rust bubbles. Open each door and check along the bottom for rust-through. Older cars are designed to let a certain amount of water run down into their doors and out through drain holes at the bottom. If the drain holes get plugged with dirt, the doors rust out.

And it isn’t enough to just feel along these door bottoms with your fingers. Inspect them directly, or use a small mirror to have a closer look. Improper repairs could have been made with plastic filler. Also, check the front hinge pockets for rust and wear. Pull up on the driver’s door to determine how much play is in the hinges. A little bit of hinge sag can be corrected with new hinge pins, but it indicates that the car has had a lot of use and perhaps not enough service. Close each door and check whether it engages properly or not.

Open the trunk and check for rust and repairs on the inside. Pull back the mat and check for rust-out in the floor. I recently heard of a floor that was patched with anti-static cling patches for the laundry, and POR 15. These are great products, but not when used for such purposes. Look at the recessed molding for the trunk seal. Is it rusty and damaged? Is the seal hard, cracked or torn? The seal is easy to fix, but a rusted-out molding is not.

By letting your eye follow the highlights down the side of a car you can often spot repairs using filler. But the easiest and best way to check for filler abuse is with a refrigerator magnet. Don’t use a strong one because it can actually stick to metal that is 1/8” or more below the paint surface. If the magnet refuses to stick in a spot, it tells you that a repair has been done using too much plastic. Also, check anywhere you see a ripple or irregularity.

Next, get down low and check to see that body panels line up along the bottom. If panels don’t line up it may be because they were removed and then installed incorrectly, or that the structure under the panel is bent due to collision or rust.

Check panel gaps around the doors, hood, trunk and fenders. If you see gaps that are too tight or too loose they most likely have been repaired and then installed incorrectly, or the car may have been in a collision that knocked its frame or subframe out of alignment.

If you really want to check a car out thoroughly for rust, you can use a Hawkeye Borescope to peer into inaccessible areas for rust and problems. These also are good for checking combustion chambers and cylinder bores through the spark plug holes. These devices were designed for checking rifle bores and use fiber optics to send light through a tiny lens at the end of a probe that can be focused. The tool isn’t cheap, but if you are going to be working on cars regularly it could save you money in the long run.

Consider a Dull Look

On older cars it is far better if they have a dull original finish than if they’re wearing a new cheap paint job. That’s because you can scuff and paint over an original finish pretty easily, but you won’t want to do that to a cheap second-effort paint job, or even an expensive one for that matter, for a couple of reasons:

The problem with painting over previous work is that you don’t know how well the car was prepared before the top coat of paint was applied. Anything you put on top of a cheap paint job will only adhere as well as the coat beneath it. There also are occasional problems with compatibility between paint systems of the past and the ones used today. And in any case, if the paint on the car is more than 4 mils thick it will be prone to cracking.

As a car’s sheet metal body expands in the heat of the sun and contracts at night while cooling, the paint on it is stressed. And if it is too thick, it will expand and contract at different rates causing layers of paint to delaminate.

Also, hairline cracks will form, and moisture inevitably will get into the cracks and rust the metal below. There is a good chance you won’t see any of this activity until the paint starts to bubble and flake off.

From Cosmetics to Mechanicals

Only after you have looked a car’s body and sub-frame over for rust, collision damage and poorly done repairs, should you move on to checking out your prospect mechanically. That’s not to say that a seriously rusted car is worthless. Some rusty cars are mechanically sound and make good parts cars if you can get them for a reasonable price.

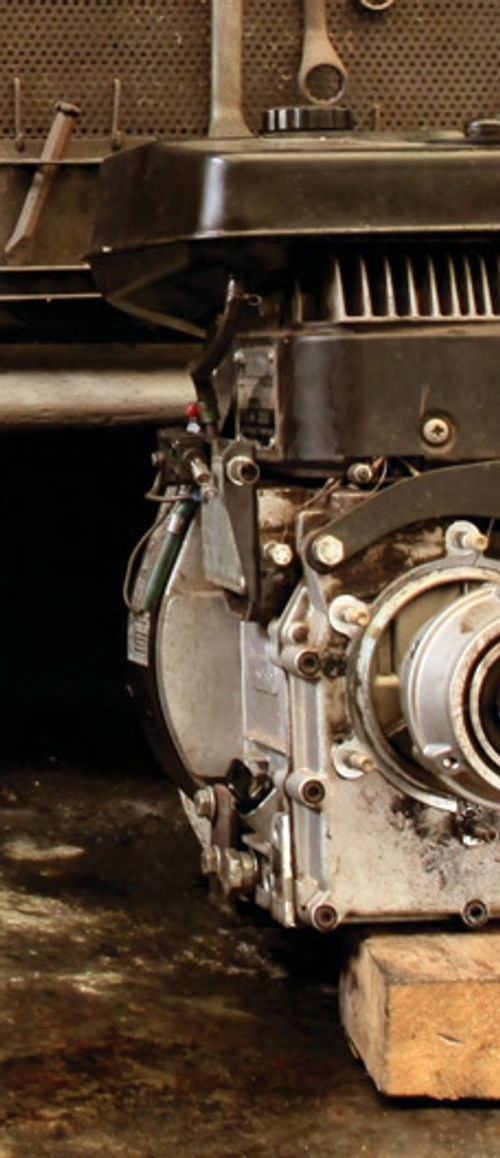

But whether you’re considering a vehicle as a project or a parts car, you’ll need to know what to look for. In an upcoming issue we will tell you how to check out the chassis, steering and suspension as well as engines, transmissions and differentials. Such components can almost always be overhauled or rebuilt, but you will want to go into such projects with your eyes open regarding costs and potential work involved.