A Restorer’s Story 1951 Willys M38 Jeep

At First He Wasn’t Sure If His Project Had Been the Right Choice. But Then the Veterans Started Appoaching Him…

Editor’s Note: With Memorial Day coming at the end of the month, we felt that this story about an Army Jeep made for a timely and interesting read regarding the restoration of vintage cars and trucks in general, and military vehicles in particular. As always, please feel free to share your thoughts on the topic with us.

I wAS At a local car show recently with my vehicle, a 1951 Willys M38 Army Jeep, when I noticed something strange: An older guy was standing next to the Jeep just sniffing the seat back. He seemed almost in a trance. This might have made some car owners nervous. They might have feared an impending violation of the sacred “Please look but don’t touch” rule. But I wasn’t worried.I knew he was just momentarily in another place and time, lost in the memories that only certain smells can evoke.

I’d seen this before. At an earlier show, a guy came up to me breathing deeply through his nose saying, “I knew I smelled a Jeep.” While many think they smell the drying of paint from a fresh restoration, what they’re actually picking up is the odor from the waterproofed canvas seat cushions—reproductions installed to keep the Jeep as authentic as possible. The smell is that of an old pup tent, for any of you dating back to pre-nylon days. For most of us, the smell is of mold and mildew. For these guys, it smelled of basic training, supply rooms and, all too often, war.

An Added Reward for His Hard Work

The Jeep wasn’t my first choice as a restoration project. As I’d imagine is often the case with restorers and their cars, it found me rather than the other way around. A neighbor of mine, the proverbial packrat, had bought it at auction from a psychiatric hospital which had originally acquired it as government surplus to use for grounds maintenance. Along with a number of missing parts and its rough condition from hard use, one of their patients had reportedly dumped floor sweepings into the crankcase, putting an end to its snowplowing career.

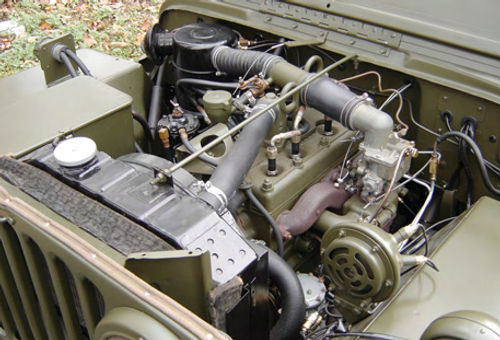

My neighbor stored it in his garage for about 15 years before finally acknowledging that he would never get to it. Needing both space and money, he sold it to me. This was my first attempt at a full restoration and I wasn’t prepared for the job myself at the time. I did a thorough rebuild on the engine (during which I found that patient’s floor sweepings still stuck in the oil fill tube), dismantled the entire vehicle and began cleaning up the frame and suspension.

But, as happens with many of us, other diversions (boats) and responsibilities (house) gradually took precedence. So the Jeep was pushed to the back of my leaky garage and there it sat for another 15 years or so stored under a tarp.

Eventually my own space, time and money limitations forced a hard decision: Either sell the boat and concentrate on the Jeep or vice versa. At first, the Jeep was doomed. I listed it for a cheap, quick sale and got an immediate taker. But the night before he was to come for it, I had a change of heart. A full restoration was something I always wanted to do and I had a good first subject for such a project in-hand. It was relatively simple, parts were available and there is just something about an old Army Jeep. So, bye bye boat.

I tore back into the Jeep with renewed vigor, added experience and a more realistic plan of attack. The body tub presented the greatest challenge, having rotted even further in its years under the tarp. It forced one of the most fundamental choices facing any restorer: how much to actually restore versus simply replace. Entire reproduction body tubs are available for these Jeeps, and this most certainly would have been the cheaper, quicker option. But I just couldn’t see going that route. When I look at a restored vehicle, I want to know I’m looking at something that is at least primarily the original. Otherwise, you’re looking at a “kit” that someone simply assembled from repro parts.

So I opted to go the full restoration route, replacing those panels on the tub that were simply too far gone, but saving original metal wherever possible. Knowing my limitations on sheet metal, I left this part of the project to Ted Olenski of Ted’s Auto Restoration Ansonia, Connecticut, who did a great job. One thing I’ve learned over the years is that you can’t always do everything yourself and teaming with skilled craftsmen who will work with you through the project is critical.

I truly enjoyed the process and am satisfied with the results. After Two-to-three years of work, the Jeep has turned into a real crowd-pleaser.

For some reason, everybody loves an Army Jeep. Maybe it’s because of what it represents: good old American ingenuity producing a rough, tough, simple vehicle ideally suited to its purpose. Or maybe it’s empathy for anything in plain olive drab sitting next to all those beautiful show cars. After all, it ain’t easy being green.

Regardless, the Jeep has turned into a memory-inducer and an ice-breaker, especially with veterans. My father was in the Army Air Corps in World War II. Like him,I’ve found that many veterans, particularly those who saw combat, often don’t want to talk about their experiences. They did their duty, returned to civilian life and preferred to move on, striving for normalcy after the wholly unnatural environment of war.

Yet the Jeep somehow get them talking. It establishes a camaraderie between us, despite my never having served in the military. It makes these guys feel comfortable enough to loosen up and tell me things, stories that I sometimes sense they’ve probably never told anyone before.

There’s a Spectrum of Memories

Those stories can range from the horrible to the hysterical and span timeframes from World War II to the present, despite the fact that my Jeep is specifically Korean War vintage.

For instance, I’ve had a number of Vietnam Vets Relate stories to me involving the Jeep, telling me my model apparently was still in use right up into the 1960s and Vietnam. They may be mistaken, as there have been many Jeep models throughout the years, often looking very similar. Regardless, to them the Jeep is more of a generic type, so it still serves as a conversation-starter.

One veteran, for example, recalled how a favorite guerilla tactic of the Viet Cong was to sneak into camps at night and, finding an unguarded Jeep, pull the pin on a hand grenade, tape down its handle and drop it into the Jeep’s rather large gas tank opening. The gasoline would eat through the tape, causing the grenade to blow up the Jeep and everything else around it, but only after giving the guerillas time to make their getaway. The GIs in the motor pool started welding hasps on the filler necks and caps so that they could be padlocked at night to thwart the Viet Cong.

At another show, a World War II vet asked me whether I was familiar with a large, inverted “V”-shaped bar mounted to the front bumper and sticking up in the air on some early Jeeps.

I said I had seen pictures and thought these might be some form of tow bar. He corrected me with the sobering fact that they were actually devices to catch and cut wires that the enemy often strung across the roads at neck-height. Thisfield modification had come too late for several of his buddies during his wartime tour in Europe.

On the lighter side, many recalled harrowing, but happily-ending stories. These usually involved a group of 18- or 19-year-old GIs, away from home for the first time and looking to burn off steam, often at the wheel of a Jeep.

Races down airstrips, rollovers in ditches and hill-climb competitions seem to be common pictures, often painted with a backdrop of generous quantities of alcohol.

Forsome, their Jeep exploits were the closest that they had come to being injured during their time in the service. In looking back with the wisdom of their years, they admit they were lucky.

Expert Advice Available

The ex-motor pool guys also are a wealth of knowledge. As with many military vehicles, aircraft and other pieces of equipment, the ordinary GI in the field often discovered shortcomings and developed simple but effective workarounds that were later put into production.These men knew every nut and bolt on the vehicle and could tell me what was standard and what was not.

This can be important because unlike the restoration of “normal” vehicles, working with a military Jeep involves frequent questions as to what you are restoring the vehicle to: The way it was when it rolled out of the factory? The way it might have actually looked in the field with motor pool modifications? The markings it might have carried in a particular theater of operations, branch of service or unit? The variations are really extensive and conversations with these men have been incredibly valuable.

Winning Trophies Can Be Very Nice, But…

The stories have been so varied, and the storytellers so interesting, that I find this has become my main reason for attending the shows. I never was interested in the whole judging scene and trophy competition in the first place. I really looked forward to the events as an opportunity to talk shop with other “car guys” and appreciate their work. I have to admit, though, that I really was tickled to win a couple of “Best in Class” awards, for no other reason than it was a confirmation that I had done the job right in the eyes of people I respect who have been there and done it themselves.

Still, the people whose appreciation and conversation I seek the most are the veterans. Despite the sometimes negative experiences the Jeep brings back from the recesses of their memories, they almost always thank me for preserving a piece of history that had such an impact on them and the world.

It’s More Than a Collection of Metal, Glass & Rubber

This past Veteran’s Day, after the car show season had ended for us here in the Northeast and it was getting time to put the Jeep away for the winter, I took one last ride. I first stopped at the cemetery where my father is buried and reset the smallflagsthatmark his grave, and several others there, as veterans’. I then stopped by a small memorial park we have here in town. I read the plaques and the markers and thought about the sacrifices these men and women made for our country, and the times in which they had lived.

Looking back at the Jeep parked at the curb, it seemed as though it were a part of the monument. Perhaps, in a way, it is.

Perhaps that’s part of the appeal of restoring a vehicle.

In doing the restoration, one learns not only about the vehicle’s history, but about the time period in which it first travelled the roads as well. You begin to appreciate the thinking that went into its design and construction and how those elements were shaped by the times. In restoring a car, you not only preserve history, but better understand it. And in driving that restored vehicle, you may—for a moment— almost re-live it. It’s not that I want to dwell in the past, but experiencing it brings better perspective to the present.

In looking for my next project, I Really wanted to satisfy my long-held desire to build some sleek hot rod, or at least something I’d get more use out of than an old Army Jeep—something that would do more than 50mph, with a suspension that would allow my kidneys to withstand greater distances. Yet, I did consider doing another Jeep when I came across one needing attention in a neighboring town.

There are the practical advantages, of course: I have a knowledge of the vehicle along with an existing collection of spare parts and a network of contacts for information and services.

But I have to admit the real temptation is to see whether I might bring out even more interesting veterans’ stories. After all, what if they saw a whole convoy arriving at the next show…