A Military Mechanical “Mule”

Some Vietnam Vets & Movie Buffs Will Recognize It Immediately. Just Don’t Go Thinking It Makes for an Easy Project.

WHEN SHEILA ZELASKOWSKI puts her Mechanical Mule in a parade, there’s one group of spectators who know exactly what it is as soon as they see it.

“Some people do recognize it,” she said. “Vietnam Vets, a few.It’ll be Marine vets because the Marines used them a lot more than the Army.”

They’ll know it because of the era in which the Mule was built and because it was well suited to the conditions it faced in Vietnam. Formally known as the M274, the four-wheel-drive, four-wheel steer Mule was built from 1956 through 1970 and despite its size—it rides on a 57-inch wheelbase and all of its variants weigh less than 1000 pounds—it’s rated as a half-ton truck. That means it’s capable of carrying more than it weighs, but less often remarked is that the Mule grew out of thinking not entirely like that which led to the original jeep.

Preceded by a Belly flopper

Motor vehicles came to the American military nearly a century ago. Jeffery Quad four-wheel-drive trucks and Dodge touring cars were a part of General John Pershing’s 1916 expedition into Mexico, and World War I Saw the use of everything from Model T Fords to FWDs.

Horses and motorcycles were maneuverable while the purpose-built military vehicles of the day were not, and that gradually became very apparent. The Model T, the Chevrolet Light Cross-Country Car and even some experimental American Austins proved the validity of small military vehicles, as did a prototype known as the Howie Belly flopper to a lesser extent.

At least partly because of its name, the Belly Flopper comes up in almost any discussion of early military or four-wheel drive vehicles and while it was unconventional and impractical, the 1937 creation of Colonel Robert Howie and Master Sergeant Melvin Wiley made its point. Essentially a self-propelled platform with no real body, the Bellyflopper’s driver was in a prone position— hence the name—and relied on little more than the fenders and an overall low profile for protection, but that wasn’t the odd part. Howie had begun with an American Austin and had—for lack of a better description—sort of turned things around; the engine was at the rear, as was the steering, while the driven wheels were up front. Ground clearance was minimal and the suspension amounted to whatever give and flexing the tires and chassis could provide, but tempting as it is to dismiss the Bellyflopper with a laugh, it was a step in the progression that finally produced the jeep.

For Military uses ranging from combat to supply to administration, the jeep was superb and nobody regretted that the Bellyflopper had never gotten beyond a single prototype. The jeep could do most of what the Bellyflopper could have done and far more, but the idea of a military vehicle smaller than a jeep never actually went away as the May 1948 issue of Popular Science demonstrated when the magazine reported on the Jungle Burden Carrier, “a pint-size jungle buggy, as versatile as it is small.”

PS noted that “it can carry half again as much as its own weight, and can go places that might drive a mule mad. Designed by Willys-Overland, this baby brother of the Jeep was originally planned as a litter carrier near the end of World War II. Field tests at Eglin Field, Florida., however, proved it equally valuable for carrying supplies and men over rough ground.”

The Jungle Burden Carrier is clearly the Mule’s ancestor. Their heights, wheelbases and lengths are close, their suspensions are their tires and while the JBC is steered with a tiller instead of a wheel as on the Mule, the two vehicles share one key design feature.

“The (Mule’s) steering wheel has three positions,”Zelaskowski explained. “You can drive on it and use all three gears, high and low. Then you can move the steering wheel, set the throttle and keep it in reverse and walk behind it. Then you can bring the wheel all the way down so that you can crawl behind it if they’re shooting at you. That’s a good thing; that you can keep moving.”

When operated from the conventional position, the driver sits on the single seat and places his feet in a basket that overhangs the platform.

Combining the Mule’s Small Size—just under 10 feet overall—and its unusual layout creates an image unlikely to be forgotten or misidentified, but in addition to the veterans mentioned earlier, there’s another group that recognizes it without hesitation, although its level of familiarity is not from direct experience.

“Aficionados of ‘Full-Metal Jacket’ will say ‘oh, yeah, that’s that thing that kept driving through,”Zelaskowski explained.

That movie, in fact, was what introduced her to the vehicle.

“I was saying ‘what is that? I want one. That is the coolest little thing.’”

It was more than just talk and in late 2004, she followed up on a tip from a friend active in the military-vehicle hobby.

Bill knew I was looking for one,” she recalled, “and he said ‘there’s a guy named George in upstate New York and he’s selling them,’ so I called him and went up to look at them and George had five. George had a lot of stuff. He’s been collecting it since he came home from Vietnam, apparently, and he’s just got a heck of a collection.

But he said ‘you can’t buy one. You buy all five or you don’t buy any and I want this much money for them.’ That was his speech for everybody who ever came by. ‘You buy all five or you don’t buy any because you all want to leave me with the crappiest one and what am I going to do with that? So you buy them all and you can probably build two good ones out of that.’

“So my boyfriend-at-the-time and I rented a box truck, went back up there and it was cold. It was in November or December of 2004 that we got them. We had to break them free of the frost, get them into the truck, stack them one on top of the other so there were two stacks of two and one sideways pushed up against the others. They all fit in the 25-foot box truck that I rented.”

Little Known About Its Past

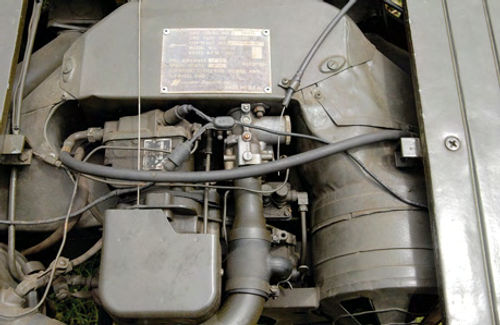

Several manufacturers built the Mule in six variations and Zelaskowski’s Mule featured here is anM274A4.It began life as an M274A1 and became an A4 when its Willys four was replaced with a Hercules twin. Both engines are air-cooled and while the Willys produces 16 horsepower, the Hercules produces 13.5. The Mule’s build-date and even which contractor produced it are unclear.

“There was no date on the data plate and when I re-stamped the new one,” Zelaskowski laughed, “I gave it my birthday…it was built in the ’50s sometime. That’s about as close as I can get and that’s a problem. I could run the serial number, but they don’t have those records computerized.”

A “BMY” stamp suggests that it was built or modified by Bowen-McLaughlin York, something else that a trace of the Mule’s paperwork might answer. Missing those two facts isn’t exactly fatal, of course, and it made little difference as far as the restoration work was concerned. Remember, Zelaskowski bought five Mules, and since the plan was to restore all of them, she got to know the parts suppliers.

“When they heard me on the other end of the phone,” she said, “they were hearing ‘ka-ching’ because if I bought for one, I bought for all five. I figured ‘if it was bad on one, it’s going to be bad on all of them and the parts are getting like hen’s teeth. Let me just buy them all now.’ I bought in bulk all the time. With all that, we got three of them running.”

The fourth was sold and is now running for its new owner while the fifth is still awaiting its turn. When Zelaskowski bought them, none had problems rising to the nightmare level despite their original condition and years in storage, but she confessed to the condition that’s overcome every restorer at some point.

“When I Look at an old car,” she admitted, “I never see the rust bucket in front of me; I see it in the auction afterward.”

Military Mechanical “Mule”

GENERAL

Truck, platform, utility, 1/2 ton, 4x4 M274A4

ENGINE

Type Hercules A042 overhead valve air-cooled twin

Displacement 42.4cu.in.

Bore x stroke 3 in. x 3 in.

Compression ratio (:1) 6.5

Carburetor Single-barrel

Power 13.5hp@3000 rpm

Torque 26 lb.-ft.@2300 rpm

DRIVETRAIN

Transmission Three-speed manual

Transfer case Two speeds

STEERING

Four-wheel with two-wheel lockout, three-position column

SUSPENSION & BRAKES

Solid axles, rigid mounting,low-pressure tires

Brakes (f/r) Internal expanding, mechanical

MEASUREMENTS

Wheelbase 57 in.

Length 118.35 in.

Width 49in.

Height 49.12 in.

Weight 970 lb.

Track (f/r) 40.5/40.5 in.

Tire Size 7.50x10

One Way to Get New Tires…

None of the five Mules seemed hopeless, she recalled, and there was the assurance that they’d run when they were parked some 20 to 30 years earlier.

“(The feature Mule) was rough,” Zelaskowski Said, “but it wasn’t too bad. Themotorwasn’tseized, we didn’t have to do anything to the motor. A lot of seals usually go bad in the wheels and in the transmission,so we had all that. We redid the seals in the wheels and all, but the drivetrain was pretty good.

“We had to straighten a lot of things out; most of it was cosmetic. Just From sitting around for so long it oxidized, so we had to try and fix the bed. That one really didn’t need as much work as some of the others needed.”

Among those cosmetic items was the cover over an opening in the bed through which two-wheel- or four wheel-steer is selected. It’s a small but rare piece.

“One of the guys who sells the parts took an old Mule bed,” Zelaskowski said, “and had some fabricator cut it all up and make these covers. They’re expensive, too. You know, if it’s hard to find, it’s going to have a hefty tag to it.”

The problems that went beyond “cosmetic” were in some cases directly related to the Mule’s military life,such as the platform’s side rails that had been damaged when used improperly.

“I needed a few of the rails,” Zelaskowski said, “I needed a steering column, I needed a seat because seats just rot away to nothing, and I needed tires. The rims, I think I needed a couple of rims for that one as well, so it was hard finding the parts. I had called Coker Tire and they weren’t making tires for Mules. I kept pestering them so much— and I wanted 20 tires because I had five Mules—that they finally announced a run of Mule tires.”

Don’t Let Its Size Fool You

The restoration required five months and that doesn’t sound bad until an important detail comes out.

“We didn’t do much else,”Zelaskowski said. “It was just working on the Mule.”

That leads to something that isn’t obvious at first glance: There are points to consider before buying a Mule and not all of them are exactly the same as a more conventional vehicle might present.

“Because you look at them and they’re small,”Zelaskowski said, “you think ‘oh, this is a project I can take on. It’s little.’

“Well, it’s got just as many parts as a car and it’s just as much effort. I had a ’68 Mustang and I did a lot of work to that, so I know what it is, and I had a 1980 Toyota pickup. We ripped that down to nothing like we did the Mules and rebuilt that truck, so I know.”

The rough rule of requiring restoration space equal to 2.5 times a vehicle’s footprint is applicable to the Mule, she agreed, and that presumes the would-be restorer haslocated one that’s worth the trouble. She spoke of seeing Internet sites selling Mules that needed nearly everything, but said that the odds of finding a good one will improve when patience and common sense are applied.

“If you know where to look,” she said, “if you’re looking in the club newsletters, you’ll find at least one or two. Trying to find one at your price might be a little bit harder.It’s Like any other vehicle. You want to talk to the people who own them so that you know. ‘This is what you’ve got to look at. Look for the leaks here, look for cracks here.’”

When she followed that advice and sought input on a New England Mule she was considering before the five-piece deal came along, she found herself being urged not to buy it.

“I drove to Rhode Island,” she recalled, “and it was an older one there that still had the Willys motor in it. Everybody I called said ‘you don’t want that one.Just walk away.’ I said ‘really?’ ‘Yes. Those motors are so problematic that you don’t want it.’ So, if it’s the four-cylinder Willys motor, you don’t want it. That’s not a dig at (Willys). It’s just the motor in that configuration at that point in time didn’t work as well. They overheated a lot.”

If that seems harsh, the fact that early Mules were modified with replacement engines while still serving suggests that it’s probably accurate and Zelaskowski said she knows of no serious problems with the later two-cylinder. Beyond ensuring completeness and looking for minor leaks at seals and for damaged components such as the rails and seat mentioned earlier, as well as cracked axle housings and a bent basket where the driver’s feet ride, she said it’s important to check the platform carefully as another Mule-owner learned.

“Where the steering column is mounted on the bed,” she said, “it tended to tear. In the bed, there would be a crack. When you looked at that Mule, there was a seven-inch crack. To find somebody who’s willing to weld magnesium was a challenge and when he did weld it, he really charged a lot of money.”

All but the final variant use the magnesium bed and the M274A5 uses aluminum. That could be enough of a consideration to stop some restorers from wanting one and like many military vehicles, a Mule’s not for everybody.

On the other hand, accept it for what it is and it might well be worth the effort of dealing with its personality.

A Mule With a Soft Seat

“It’s a lot of fun to drive,”Zelaskowski said. “You’re out in the open and so you’ve got to be mindful, but it feels like you’re going faster than you really are because you’re right out there on the fender. You have to be careful. I’ve had people tell me how they rolled them or they flipped them; that their mules kicked them off. Fortunately, I’ve never done that with mine.

“I think it’s pretty forgiving. As Long as you know where you’re at and you have a healthy respect for the equipment, that’s it.”

Part of that healthy respect is being aware of the four-wheel-steer and its effect on handling, but it’s a feature that can easily be locked out to provide conventional two-wheel-steer. Neither makes a difference as far as ride, of course, and Zelaskowski said the Mule’s seat is the most comfortable in the military.

Comfortable or not, the 25 mph top speed and the fact that it’s not really a road vehicle mean Zelaskowski generally trailers her Mule, but parades are another matter.

“The Mule’s not a hard thing to drive at a slow speed because it’s geared low,” she said. “I’ve driven pretty much everything in a parade. I’ve driven the deuce and-a-half, CUCV, jeeps and yes,some of them are a real pain because they’re just not geared that way. It’s constantly clutch-brake, clutch-brake, clutch-brake, but with the mule, you can time it and just keep it in first low and let it go. That’s actually a pleasure.”

Starting One Calls for Extra Work

Some parades have gone smoothly, some haven’t. A Veterans Parade in New York City was uneventful, while a July 4 parade in Chatham, New Jersey, resulted in a flat tire and a quick demonstration of counterbalancing. A parade in upstate New York required a flat-out drive from the staging area to the starting point through a rainstorm. In a Netcong, New Jersey parade, the Mule refused to start after stalling, thus inspiring comments from spectators about “that’s why they call them mules. They’re stubborn.”

Zelaskowski’s Mule was built with a pull-starter, but even with the electric replacement she installed, there’s a sequence to a cold start.

“You have to pull the choke out just so and you have to have the fuel lever set just so,” she explained. “You have to pump it a couple of times. I have a trick where I hit the kill switch so that there’s no spark, but it’s turning over. That’s to prime it a little bit and then I’ll let go of itso that it’ll start. So yeah,she’s got her little ritual to get her started and I can’t just let you go. After she’s been started and warmed up, then I could just say ‘there you go. Hit the ‘start’ button and you’re off.’”

She also noted the warning she’d give before letting the hypothetical driverstart it. Anyone who’s ever crank-started a vehicle has probably thought about it and anyone who’s been unexpectedly pursued by a creeping Model T always thinks about it.

“You have to instruct people to make sure that it’s out of gear,” she said, “because if it’s in first gear and you’re standing in front of it starting it, it’s going to run you over.”

Long-Term Partners

Parade use and other light-duty service amount to a long-term vacation for military vehicles, while some are worked into the ground during what should be their retirement. Zelaskowski said she keeps her Mule looking as close as possible to the day its restoration was completed. It shows some chips and scratches, but she agreed that if it were perfect, she’d be too worried about driving it to enjoy it.

“Exactly,” she said. “And that kind of negates having it, doesn’t it?”

What’s probably the least surprising part of the whole story is that the feature Mule isn’t going anywhere.

“A couple of other people I know who had them,” Zelaskowski said, “have since sold them and regretted it. They’re going to have to bury me with this.”