A Continental Mark II “Survivor”

Sometimes, You Can Decide If You Want to Restore or Preserve. With This Car, Rarity Plays a Role In the Decision.

Editor’s note: Lately we’ve been hearing more about well-preserved vehicles that over the years have only been repaired and maintained to a level that keeps them looking good and in roadworthy condition. So, we figured it’s time to take a closer look at some of these vehicles, such as the Mark II on these pages.

I’VE OFTEN BEEN asked whether it’s better to leave a collector vehicle as-is if it’s mainly original—known as a “survivor”—or to restore it. The bottom line here is that there’s no pat answer; it depends on a lot of factors.

For starters, there are questions you should ask yourself when trying to determine which road to take.

For instance: What motivated you to buy the car? What do you want it for? What are your expectations?

When you answer these questions, making the decision to restore it or leave it as original as possible will, hopefully, be a bit easier. There are some other important things to consider as well. First and foremost, remember the old saying: A car is original only once.

Also, if you purchased the vehicle with an eye toward it bringing you a financial return in the future after you restore it, then you’d better plan on putting it in a hermetically-sealed bag and keeping it in a climate/humidity-controlled storage facility until the market for this vehicle is as ripe as your expectations. I say this simply because it’s a fact that if you drive it and use it, without a shadow of a doubt it will deteriorate from the condition it was in when the restoration was completed.

On the other hand, if you want to have some fun driving it, one approach is to only do the repairs and maintenance necessary to keep the car running well and safe. This is the route my late brother, Tim, took with the 1956 Continental Mark II seen on these pages.

It Made a Lasting Impression

My brother, Tim, related a story to me about when he was in his early teens and he and my dad saw a Continental Mark II in a “filling station” getting gas; this was around 1955 or 1956. My dad pointed to it and told Tim, “Son, that’s a rich man’s car!”

Indeed, my dad spoke the truth. With a sticker price just shy of $10,000 in 1956, the Continental Mark II rivaled the price of a new Rolls-Royce. Apparently, my dad’s comment stuck in Tim’s mind and, some four decades later when the opportunity to purchase a Mark II presented itself, he jumped on it.

He bought the car several years ago and became the third owner of this huge land yacht. The car was exceptionally well-documented and had only about 49K miles on the clock when he acquired it in July 2000. He dubbed the car “Big Blue,” and it was his pride and joy. The Mark II was in extremely good condition considering it was more than 45 years old at the time. The key words here are “extremely good” but not “perfect,” mind you. The old girl was definitely showing her age, but still looked and ran very respectably. Tim had bought the car to drive and have fun with, so restoring it was not an option he was considering.

Prior to his unexpected death in August 2008, Tim enjoyed tooling around in “Big Blue” to go to cruise nights, car shows or even to the local Dunkin’ Donuts for a cup of joe. In fact, he attended a cruise night with it just five days before he died, so I’m glad he got to have one last ride in his favorite toy. And now, here’s a bit more about the car itself.

A Car for the Rich and Famous

In a move designed to underscore its chic nature, the Continental Mark II made its debut at the Paris Auto Show on October 6, 1955. The car was intended to appeal to upscale buyers who wanted a vehicle equipped with every known luxury feature of the day…and all of these were standard equipment on the Mark II with the exception of air conditioning, a factory option, and the electric eye high-beam dimmer, which was dealer installed. The Continental Mark II was only available as a two-door hardtop coupe. However, two (some believe three) were special ordered as convertibles and were sent out by Ford for the custom coach work. The two known examples have Ford-authorizing paperwork. Others that exist are unauthorized aftermarket productions.

Along with living in the rarified pricing air of a Rolls-Royce, the Continental Mark II’s sticker price of $9966 was more than double the tab for a 1956 Lincoln or Cadillac. In fact, the Mark II was Ford’s bold attempt to cut deeply into the Cadillac-dominated luxury market. After all, only the extremely well-heeled of the day would have had pockets deep enough to purchase one. Consider that the rich and famous of the mid-’50s who owned Mark IIs included Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Louis Prima, Dwight Eisenhower, Barry Goldwater, Spike Jones, Nelson Rockefeller, Cecil B. DeMille, R.J. Reynolds, Bill Harrah, Henry J. Kaiser, Howard Johnson, the Shah of Iran, and Mrs. Charles C. Gates, wife of the Gates Rubber Company magnate, for whom the car featured here was purchased.

No, It Wasn’t a Lincoln…

Contrary to popular misconception, the Mark II was not made by Lincoln, but by the short-lived Continental Division of the Ford Motor Company. There never was a model designated as a Continental Mark I, although the 1941-42 Lincoln Continentals and their nearly identical post-war 1947-48 siblings are often incorrectly called Mark I.

The Continental Division was started by Edsel Ford’s son, William, in response to dealer and customer surveys that indicated upscale cars would be in demand. The goal of the newly-formed Continental team was to design and produce a car that would be a tribute to the then recently deceased Edsel Ford that would be elegant, comfortable, powerful and would attract the rich and famous. The goal was to make a car that was as well made as it looked—literally the “Rolls Royce” of American cars. The styling of the Continental Mark II was called “Modern Formal,” which was—and still is—a catchy marketing term.

It’s also important to keep the economics of the period in perspective with regard to the Continental Mark II. This, after all, was an era when a typical family’s yearly income was around $4000 and a mid-level car could be had for less than $2500.

Why was this car so expensive? The fact that it was largely hand-made had a lot to do with the price. For example, while the Continental shared some drive train and suspension components with production Lincolns of the day, other than that it was a totally different car. The Continental was equipped with a new perimeter frame with the floor pan attached to the bottom of it for “stepdown” entry. A low driveshaft tunnel that housed an expensive and complicated three-universal driveshaft was also developed specifically for this car.

The standard 368 CID 1956 Lincoln engine was used in the Continental but only after each one was carefully balanced, blueprinted, test-run and inspected for unusual wear. Every Continental’s transmission was tested in another vehicle, also disassembled for inspection and then installed in the new car. All hardware was aircraft quality and carefully torqued.

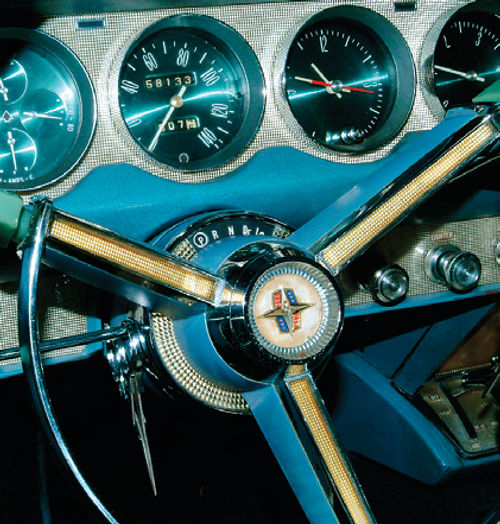

The Continental’s interior was certainly luxurious, with Bridge of Weir leather seats, plush carpeting and special instrumentation. The painting standards for the car gave them “show” finishes, far better than what the public expected and heads and shoulders above the “normal” automotive finishes of the day.

Short Run for a Big Vehicle

There is no question that, although it looked lean and elegant, the Continental Mark II was still a very big car. It had a 126-inch wheelbase, an overall length of 218.4 inches and its curb weight was 4825 pounds—almost 2.5 tons! While the hand-assembled Lincoln engine put out 285 HP, pulling a land yacht of this size and weight caused the 0-60 mph time to be almost 16 seconds and fuel mileage was an abysmal 13 mpg. But, in those days you could fill the tank with high-test for under $5 and, if you could afford a Continental Mark II, you certainly weren’t concerned about gas mileage or economy, for that matter.

The Continental Mark II only had a two-year production run, with a total of 3000 units built between June 1955 and May 1957. For even with the car’s $10,000 price tag, the Continental Division claimed a loss of $1000 on each car it produced. Because it wasn’t selling well and Ford was losing over $1 million a year, production was stopped in May of 1957. The Continental division was handed over to Lincoln and, ironically, the production plant was converted to manufacture the new Edsel.

A Well-Traveled Car

Because of the limited number produced, restoration parts are pricey and hard to find, thus making a restoration an expensive proposition. By comparison, 1955-57 Thunderbirds produced during the same era abound, are easier and cheaper to restore, and sold for around $3000 when new. Yet today they command higher dollar values than Continental Mark IIs.

The Continental Mark II featured here, VIN C56A 1670, was purchased on November 10, 1955 by Charles Gates for his wife, Hazel. Gates, the founder and owner of the Gates Rubber Company, insisted that the car be equipped with Gates tires rather than the OEM Firestones, thus making this car a DSO (Dealer Special Order) vehicle.

The 8.20x15” Gates 4-ply whitewalls were shipped to Dearborn, where they were installed on the car during assembly. The car was ordered through a dealer in Denver, Colorado, and delivered to the Matson Navigation Company in Los Angeles, who then shipped it to the Gates’ vacation home in Honolulu. The car was eventually returned to Gates’ Colorado estate.

Charles and Hazel Gates both died in 1973 and their children sold the Mark II, with 44,000 miles on the odometer, to a collector from Colts Neck, New Jersey. He intended to restore it, but got involved in restoring other vehicles in his collection instead and never got around to the Mark II. He put another 5000 miles on the vehicle, “exercising” it every so often.

Tim Benford (my late brother) of Mountainside, New Jersey, purchased the unrestored Continental Mark II in July of 2000 and enjoyed driving it to car shows and cruise nights every chance he got. While he had the “correct” wheel covers for the car, he used the “driver” wheel covers, shown in these photos, for casual cruising, saving the expensive (and rare) originals for judged shows (which he only rarely attended).