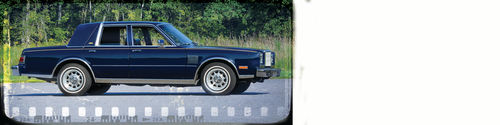

1982 CHRYSLER NEW YORKER FIFTH AVENUE

Yes, It’s From An Era When Cars Were Being Downsized. But This Chrysler’s Still Comfy Enough to Put You to Sleep.

Seller’s remorse and a little bit of luck can be a good combination when it comes to finding just the right car.

“I had had an original 1986 Chrysler New Yorker,” explained Frank Cook, whose 1982 New Yorker Fifth Avenue Edition is featured here. “It wasn’t a Fifth Avenue Edition but I was really happy with it. I loved the suspension on it. I did some accounting work out of Harrisburg and I used to drive back and forth. I think it was 16 or 17 months that I worked out of Harrisburg and it was just so nice.”

“I sold it and I wished I hadn’t.” The trip from his home in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, to the state’s capital is about three hours and so a comfortable car—or an uncomfortable one—would likely make an impression on its driver very quickly. Not surprisingly, then, after selling the New Yorker in 1997, Cook kept an eye open for a replacement. The moment arrived while he was having lunch at a local restaurant and learned from his brother-in-law about a Chrysler on a nearby dealer’s lot.

“I said ‘well, it’s right up the road,’” Cook recalled, “‘so I’m going to check it out’ and that was it. I went in and I spoke to him about it and he explained to me that the original owners had it and then their kids had it after the original owners passed away, and they gave it to him to sell.”

That was in 2002 and the Chrysler’s odometer showed about 65,000 miles, so it seems safe to guess that the family had treated it as something of a Sunday car. That makes sense because although the Imperial was at the top of the corporate hierarchy in 1982, the New Yorker was the flagship for Chrysler and its $10,851 price tag—$28,159 today—placed it squarely between the LeSabre and Electra in Buick’s range.

A Vehicle With a LargeCar History

The New Yorker name at Chrysler went back to 1939 when it was the mid-range eight-cylinder model. Two years later, it had been moved upward to become the second-costliest Chrysler. Setting aside Imperials during the years in which they were Chrysler models, the New Yorker’s only competition for the most-expensive Chrysler was the 300 that arrived in 1955 and gradually pulled slightly ahead in price. But in the letter series that ran through 1965, the 300’s focus was primarily on performance and sales were always a fraction of the New Yorker’s.

All Chryslers then were full-size cars and advertising bragged about it. In 1961 they emphasized that “there are no jr. editions. Every Chrysler is a full-size, grown-up car with real six-people room.”

That might have continued indefinitely if not for the oil embargo of 1973, the result of action by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to cut oil supplies and hike prices. Although resolved in less than a year, the actions drew attention to the size of American cars in general and resultant high levels of fuel-consumption, eventually leading to government-mandated fuel-economy standards.

The easiest way to improve automotive efficiency is to build smaller cars, but that obviously couldn’t happen overnight and the automakers were further hampered by increasingly stringent emissions mandates that were then coming into play. For several years as those two requirements collided, most cars ran poorly and saw no significant improvement in economy. Full-size models were hit the hardest and both domestic and imported compacts quickly found new popularity, but Americans were not at all unified in some sudden desire to give up large cars. Detroit knew that and although Mercedes-Benz and other European manufacturers had made mid-size luxury and near-luxury cars acceptable in the American market, General Motors became the first to offer a modern domestic contender when it introduced the 1975 Cadillac Seville.

The Seville’s 114.3-inch wheelbase made it the smallest Cadillac that year and its $12,479 list price made it more expensive than all but the long-wheelbase Seventy-Five series. At 4200 pounds, it was no lightweight, but it was about 800 pounds below that of the full-size Calais and DeVille models. Some criticized it as a Chevy Nova that had been fancied up—that was true in the most basic sense because the Seville began with the same platform—and its styling was restrained for the time, but Cadillac sold more than 16,000 examples following the Seville’s introduction late in the model year and almost 44,000 in 1976.

Ford responded with the Lincoln Versailles, a car whose major flaw was that it looked far too much like the Ford Granada and Mercury Monarch on which it was based. Introduced in 1977 at $11,500, the Versailles found more than 15,000 buyers, but its sales were up and down over its four-year life.

Chrysler followed the same pattern by turning the Plymouth Volare and Dodge Aspen into the Chrysler LeBaron and did so with an approach uniquely its own.

“A car this luxurious doesn’t have to cost $12,000,” advertising explained. “Introducing Chrysler LeBaron. $5758.” That figure included optional whitewalls, wire wheel covers, bumper guards and light package that had raised it from the base $5594 price.

Unlike the Seville and Versailles, the LeBaron was the least-expensive model in its family, a feat it managed without making buyers of un-optioned examples look like cheapskates. Standard equipment included an automatic transmission, a 318 V-8, power steering, power front-disc brakes and the requisite padded vinyl roof.

It was “the beginning of a totally new class of automobiles” and while that was a stretch, total accuracy was less important than the car itself as Chrysler sold just over 46,000 LeBarons in 1977. The Chrysler name had some magic and when the LeBaron returned for 1978, its 318-cubic-inch V-8 was joined by a 360 as well as a six, the 225. It also offered a new transmission, a four-speed-overdrive manual and advertised that “there is no other car quite like LeBaron.” The ad had a point, as unlike the Versailles and the Seville, the LeBaron was now available not only as a coupe or sedan, but also as the imitation-wood-paneled Town & Country station wagon.

Given its recent introduction, the LeBaron had never had to endure downsizing and what’s equally noteworthy is that 1979 saw sales top 110,000 examples of what was now a three-year-old design that had received merely annual updates. Sales figures were proving that Chrysler knew what its customers wanted, but in the context of the times, the LeBaron was due for more than just some new trim and 1980 brought a style that might be best described as sharpened.

The 1980 proportions were about the same and if seen from a distance the profile was about the same, too, but the roofline had been tweaked at rear and sheet metal had been subtly straightened. The taillights were still large and horizontal, but now were flanked by small vertical lights at their edges. Even more difficult to miss was the new look at front, thanks to a totally different waterfall grille. It was still bracketed by pairs of rectangular headlights, but no one could mistake it for an earlier model. Under the hood, the reliable 225 remained the base engine and the 318 was again the optional V-8, but the slightly eccentric— yet utterly practical—four-speed-overdrive was gone.

Sales reached about 63,000, but it’s not quite fair to place all the blame on the LeBaron. It was not a good time for the American auto industry, the LeBaron was on the thirsty side for a car of its size and worst of all, Chrysler Corporation was in the midst of its financial nightmare and was scaring off at least some potential customers.

Time for Some Downsizing at the Top

The show, however, did go on and 1981 saw a barely changed LeBaron. It was “prestige in an efficient size” and “a new set of values,” but sales reached only about 43,000.

Chrysler’s full-size cars were not doing even that well and the company decided to shuffle the lineup for 1982. The two big Chryslers were dropped and while that meant the end of the Newport badge, the New Yorker lived on. Thanks to a completely new line of small front-wheel-drive K-cars, the LeBaron name was moved to the most fuel-efficient models in Chrysler’s range and that gave the New Yorker name a new home on what had been the LeBaron. The New Yorker, of course, now looked nothing like its immediate predecessor and instead was just about the same as the final LeBaron, right down to the choice of a 225 or 318.

“The ultimate New Yorker has always been the Fifth Avenue,” a brochure explained of the popular high-end package. “This has not changed in 1982. But the car responding to the dictates of performance and mileage in the 1982 economy has changed. New Yorker is now mounted on a re-engineered platform that provides the famed Fifth Avenue ride and Fifth Avenue comfort in a new, even more stylish size.”

Is It a Comfy Ride? Let Me Tell You…

Cook knows all about the Chrysler’s comfort from his experience with his 1986 New Yorker and the feature car.

“When I used to drive (the 1986) back and forth to Harrisburg,” he said, “I’d have to be down there at the capital at 8 in the morning, so I’d get in my car at 5:30 and I would always get nervous because I would be (ready to nod off) driving that car down the Interstate. I always said this to my wife and to other people, ‘I get nervous a lot of times because it’s just so comfortable that you’re afraid you’re going to fall asleep in it.’ And my ’82 is just like it, absolutely.”

He knows that’s true from having driven the feature car to the AACA’s fall meet at Hershey, a comparison that’s valid because it’s just a few miles less on the same route that he used to take to Harrisburg. He also knows from making that trip that he’s not the only one to experience the car’s comfort factor.

“That’s what it was with the guys who came with me to Hershey,” he said. “I think the one guy was actually falling asleep because once again, we got up early, 3:30 or 4. We wanted to get on the road by 5. At one point, I wanted to say something to him and all of a sudden he was like ‘what?’ He said ‘my gosh, this is the most comfortable car I’ve ever been in.’”

An Untouched Rear Seat

Beyond the comfort, there’s the interior’s overall condition. Cook said that when he bought it, he learned that the rear seat had never been used. One look at the leather upholstery makes that very easy to believe and he said that it’s something noticed by judges at shows.

“They’ll look at it,” he said, “and they’ll say ‘look at the rear seat. That is really nice.’ I say ‘nobody ever sat in it.’”

Not every piece of the interior survived as well and after owning the car for a few years, he finally conceded defeat and had the headliner replaced.

“That’s one of the situations with those cars,” Cook explained, “and I can’t tell you how many times we tried to put it back up and we couldn’t, so when I go to the car shows, because it’s an HPOF (Historical Preservation of Original Features) car, that’s the one area where it’s not all-original. I took it to a shop in Scranton and he did a beautiful job. I was really happy with it and ever since then, I haven’t had a problem. It’s not fallen at all. There’s one little area that came off, but we had the glue for it and we put it back in.

“I can’t tell you how many judges have looked at it and said to me ‘that really looks original.’”

In Quite Good Condition… Except for a Badge

The Chrysler needed very little when he bought it and by the time the new headliner was in place, he’d already changed the fluids, belts and hoses and had the rear springs replaced. The interior’s use of plastic can lead to well-placed fears of tracking down replacements for parts damaged by wear, breakage or sun, but the feature car had none of that.

“One of the door handles broke,” Cook said. “It cracked. That was unusual, but I was able to get one down at (a local yard). And the front ‘Chrysler’ plate had a scratch in it and it was a bad scratch. I went to (the yard) one day and I asked him and he had an ’83 Chrysler. It wasn’t inside, it was under trees and it was in bad shape. We looked and son of a gun, this plate was in gorgeous shape.”

Following some brief negotiations, he had the badge and soon mounted it. The original went on display with the car’s trophies.

Despite the New Yorker’s having spent its entire life in northeastern Pennsylvania where winter road salt leaves a trail of destruction on many cars, the only damage to the body is in the form of stone chips. Cook said that his 1986 had some minor rust problems and agreed that the potential problem areas are about typical for cars of the time, namely the quarter panels, rocker panels, trunk floor, and fenders at both the tops and the bottoms. He said his first New Yorker was beginning to show rust along the door bottoms, but an example that was at least somewhat cared for stands a good chance of being generally solid.

Chrysler wasn’t shy when it came to describing the steps it took to prevent rust, explaining that its “corrosion protection is among the best in the industry. It includes the use of galvanized sheet metal panels, one of the best known methods of corrosion protection, as well as the seven-step dip-and-spray process.” That probably was more than hyperbole, as the nearly identical Dodge Diplomat was popular as a police car and many survived that service well enough to go on to second lives as private vehicles. They were, no doubt, helped by the fact that the drivetrain they share with the New Yorker is about as close as possible to bulletproof. Neither 318s nor TorqueFlite automatics are known as anything but excellent and chances are slim that virtually any drivetrain part would be difficult to find. Add that to the comfort that Cook cited and a New Yorker like his becomes an appealing choice for someone who wants to drive an older, interesting vehicle as either a show car or as everyday good-weather transportation.

Adjusting to Its Handling…and Gas Mileage

Using the car as a driver, of course, would call for some adjusting and familiarization. Chrysler power steering of the era, for example, calls for a light touch and therefore is both loved and hated.

“I can’t tell you how many times people have come up to me,” Cook agreed, “and said ‘I drove one of those one time and they just turn on a dime.’ They do.”

The brakes, too, can be surprising and most drivers inexperienced with anything but modern cars would need to get accustomed to them.

“Yes, you do,” Cook said, “but once again, it didn’t take me long to get used to them because of the ’86 and the way I drove it.”

While the feature car covers just a few thousand miles at most each year, he knows from the 1986 that fuel economy is not one of its selling points and said that would stop him from buying one as a driver. A similar LeBaron with a 225 and the overdrive transmission might make a difference sufficient to convince him.

“That would be better, yeah,” Cook said, “but to drive it every day, if I were to go to work like I did with my ’86? I loved it, but what was the gas back in those days? You didn’t have to be concerned about it as opposed to today.”

But is its fuel economy really that bad?

“On the highway,” Cook said, “I get about 19. Around town? Thirteen.”

An Attention-Getter

No matter where it’s being driven—or where it’s parked—it’s a very visible car.

“People come out and stand there looking at it,” Cook explained. “I’ve had people actually come and ask me ‘can I take a picture of this car?’ I say ‘yeah, absolutely’ and they take out their cell phones and take their pictures. They just look at it. They talk about the wheels,

how they’ve never seen wheels like that. One guy came over to me and he said ‘you know, I’m a Cadillac man. I like my Cadillacs and everything, but these New Yorkers were No. 1 back in the day.’ I said ‘well, I don’t know about that, but yeah.’”

The Cadillac man was among the few who can identify Cook’s Chrysler. Some ask whether it’s a Dodge and others just ask what it is. More than a few comment on the interior and the size of the trunk, two features that make a New Yorker an excellent car for long-distance driving in spite of the gas-mileage. Cook isn’t the only one to know that, as he spoke of selling the 1986 New Yorker when it showed about 185,000 miles on its odometer.

“I saw that car several years afterward,” he said. “It was down in one of the shopping malls in Scranton and I knew it was mine. I really did, and I waited until the gentleman came out. I said ‘how are you doing with it?’ He said ‘really good. I drove it quite a bit and I didn’t have any problems with it. I had to replace the carburetor at one point.’

“I said ‘how many miles do you have on it?’ He said ‘I think I’m about 1000 away from 300,000.’ The body was in a little rough shape, but he was just an older gentleman and it was his everyday car.”

And how did he accumulate that many miles?

“I think he told me he had relatives out in Ohio,” Cook said, “and he would drive it back and forth out there on occasion.”