1956 Chrysler New Yorker

This Car Was Perfect for the Rising Executive of the Day. It Has Class, Style…and a Potent Hemi Engine.

ANYONE WHO’S BEEN driving for more than a few years has encountered one of those cars that makes a very long trip seem like a great idea. It’s less a matter of finding the perfect car than it is a matter of finding the right car.

Take a careful look at the 1956 Chrysler New Yorker featured here. Today, it would fall into that slightly ambiguous “near-luxury” category, but hardly anybody used that term 53 years ago.

Those who did classify cars then probably saw it as a fairly expensive model nicely suited for the junior executive, the one who hadn’t quite reached the income level necessary for an Imperial, Cadillac, Packard or Lincoln. Since he probably was a family man, his car needed plenty of room for passengers and their luggage, but he was also on the way up (or thought he was) and required a car that could straddle a somewhat fuzzy line.

The junior executive needed to show that beyond his ability to do his job successfully, he had the taste and style to make a good impression and could pull it off without being a threat to those already at the top. A New Yorker was ideal for that, thanks to its clear resemblance to the Imperial tempered by trim that in the context of the times was mostly restrained. Driving a New Yorker showed its owner’s judgment and, in 1956, a Buick Roadmaster or a Clipper Executive would have filled the same role. The New Yorker, though, was the one with the hemi, an engine that symbolized the remarkable transformation that Chryslers had gone through in less than a decade.

An Airflow Legacy?

Few could have faulted Chrysler had it chosen an extremely conservative path following World War II. After all, something very radical indeed was probably still fresh in the corporate mind then, such as when Chrysler had unveiled the 1934 Airflow, which looked like no other car on the American road. It didn’t even look like that year’s other Chryslers. Where the boxy sixes were conventionally styled and an evolutionary step from their immediate ancestors, the Airflows were covered with gentle curves and an overall smoothness that came from a serious effort to streamline them.

The Airflow was so modernistic that it later became an icon of the Art Deco era. It broke new ground, even as it greatly disappointed Chrysler with its sales.

The company refused to give up on the new design immediately, but it quickly began rebuilding its line of conventionally styled cars to parallel the Airflow offerings.

While all of that was going on, it might have been easy to overlook the appearance of a new model name, the New York Special of 1938. A high-end eight that was built on the Imperial platform, it returned for 1939 as the New Yorker, but things from there grow complicated. A New Yorker generally is thought of as the top of the modern Chrysler line and that’s long been true, but the inaugural version was actually a step down as it was slotted below the Saratoga.

However, when Chrysler rearranged its eight-cylinder line again during 1941, it repositioned the New Yorker above the Saratoga. With that, the basic pattern that would continue for decades was established, but selling cars and remaining competitive required more than consistency in names. It was a lesson that Chrysler would learn with its first true postwar models.

Losing Ground on the Competition

With the rest of Detroit, Chrysler returned its 1942 models to production as quickly as possible after the end of World War II with just enough changes and improvements to give the cars a somewhat fresh look. Nobody complained, given that new cars had been unavailable for several years, but the more important point was that the 1946 Chryslers provided little about which to be critical. Quality cars that were finished nicely and relied on robust drivetrains, they were both practical and pleasant.

Chrysler carried over its 1948 body into 1949, when the new cars arrived midyear. The second-series 1949 line was much different from its predecessor in that it had traded the plump, prewar roundness for a soft—but very definitely boxy—quality. It was successful when viewed as a means to provide practicality, and it certainly avoided the gamble that Chrysler had taken on the Airflow, but it didn’t seem very up-to-date. And it was no help that Cadillac and Oldsmobile introduced modern overhead-valve V-8s in 1949 while Chrysler continued with its flatheads, nor did Chrysler offer anything to match the 1949 Buick, Cadillac and Oldsmobile two-door hardtops.

A Chrysler was still a quality car, even if it seemed to be facing an increasingly real danger of being left behind. Its first response to that perception came in 1950, when it introduced a two-door hardtop in both the Windsor and New Yorker lines.

The hardtops were a collective leap forward in bringing Chryslers up to date, but there were still those engines. The New Yorker, Saratoga and Town and Country again used the 323-cubic-inch, 135-horsepower flathead straight eight and to say that it was an engine that lacked boldness at the beginning of the V-8 era is to be polite. It was smooth running, durable and proven…but it was not sexy.

The Launch of the Hemi

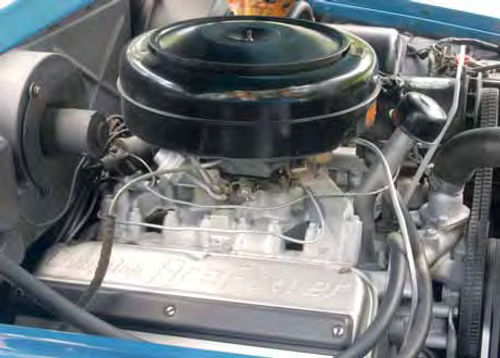

Then, in 1951, Chrysler placed something very different in certain engine bays. Available in the Saratoga and the New Yorker, the new 331 developed 180 horsepower and wore valve covers that read “Chrysler FirePower.” But while that may be a catchy name, it became best known as the hemi.

That nickname refers to the engine’s hemispherical combustion chambers and while that was a design feature recognized widely for its impact on operating efficiency, it also was one that resulted in added complexity and cost.

Besides the shape of the combustion chamber, the hemi design placed the spark plug at its center and one valve at each side of it when viewed from the front. That meant dual rocker assemblies for each head and that, in turn, resulted in the distinctive, very large heads with their deep spark plug holes.

No one had yet declared that the horsepower race was officially underway, but Chrysler was ready. The hemi’s 180 horsepower beat Cadillac’s 160 and both engines were 331s. Suddenly, it was a little harder to dismiss Chryslers as being practical and boring.

The 1951 models’ restyling hadn’t been enough to change the image significantly and while 1953 brought another update, the look was only slowly moving forward; a one-piece windshield and wire wheels became available, but rear-fender bulges and—in the Windsor—a flathead six were still there.

Still, 1954 brought some good news as the New Yorker’s hemi was now rated at 235 horsepower.

If life had improved for Chrysler fans, it did so again with 1955’s new body, increased horsepower and, best of all, an additional model.

Bearing no resemblance to the 1954 line, the 1955 Chrysler wore the “100 Million Dollar Look” created by Virgil Exner. Its sides were smooth without a trace of a rear fender, its hood was lowered and flattened, its lines were less curved and its quarter panels were showing the beginnings of fins. The Windsor finally lost the six and replaced it with a non-hemi 301 V-8 that produced 188 horsepower, but there was much more to talk about regarding engines.

1956 Chrysler New Yorker

GENERAL

Front-engine, rear-drive, four-door sedan

ENGINE

Type Overhead-valve V-8 with hemispherical chambers

Displacement 354 cu. in.

Bore x stroke 3.94 in. x 3.63 in.

Compression ratio (:1) 9

Carburetor Four-barrel downdraft

Power 280 hp @ 4600 rpm

Torque 380 lb.-ft. @ 2800 rpm

DRIVETRAIN

Transmission PowerFlite automatic

SUSPENSION & BRAKES

Front Independent, coil springs

Rear Solid axle, leaf springs

Brakes (f/r) Power-assisted Drum/drum

STEERING

Recirculating ball, power assisted

MEASUREMENTS

Wheelbase 126 in.

Length 221 in.

Height 62.9 in.

Width 81 in.

Track (f/r) 60.4/59.6 in.

Weight 4110 lb.

Tire size 8.00 x 15

In the 300’s Shadow

The hemi was now up to 300 horsepower via such enhancements as a pair of four-barrels and a better cam and Chrysler dropped that version of the engine into a new model, the C-300. Essentially a New Yorker two-door hardtop wearing an Imperial grille and better suspension, it did what it was supposed to do by winning races and drawing attention. The 1955 New Yorker today is typically overshadowed by the C-300, and had the high-performance car not been built, the 250-horsepower New Yorker would likely be better remembered.

Not surprisingly, the 1956 Chryslers were modestly restyled and—as the horsepower race had proven itself a reality not to be ignored—they were given better performance potential.

All models received new, larger taillights in what had grown into genuine fins and while what was now called the 300B looked about the same up front, the Windsor and New Yorker received cleaner grilles, the latter using a finer pattern. The New Yorker also benefited from a hemi that was bored to displace 354 cubic inches. While that enabled the 300B’s driver to claim 340 or even 355 horsepower, the owner of a New Yorker had to make do with a mere 280. But then that was reasonable; after all, a junior executive needed to show restraint as he made that good impression and so a 300B was a little over the top.

The New Yorker, on the other hand, carried an aura of dignified success along with its slightly more genteel engine. But genteel or not, the engine was a hemi and that translated long ago to a magic that’s never faded.

Lured By the Engine

“I’ve always wanted a hemi, all my life,” said the feature car’s owner, Norm Phillips of Montgomery, Pennsylvania.

His chance arrived early in 2007, when he saw it advertised in a local newspaper. His wife, Kim, was the first to look at it and included in the information she brought back was that it had a large V-8. It all sounded intriguing, despite the fact that the hemi Phillips wanted was a much later engine.

“We went up a couple of days later and ended up talking to the owner about it,” he recalled, “and he told me about the mileage on it, the story behind it and that it had the 354 hemi. At the time, I only really knew of the 426.”

Phillips finally had his hemi. The 30,000-mile New Yorker wasn’t driveable then, but the seller started it for him and it ran. It obviously needed a major tuneup, fresh fluids and the other maintenance items that generally should be replaced after a car has been unused for an extended period. Beyond that, nothing significant was wrong mechanically.

“The biggest problem,” Phillips said, “was that the (core) plugs were leaking. Other than replacing them, engine wise, there wasn’t a lot to be done to it.”

The car also received new shocks and springs, but the weatherstripping and most of the exhaust are original and even the clock functions. Having been in storage for about 25 years, the Chrysler was solid with minimal rust damage, although generations of mice had called it home and destroyed the original interior. The interior’s damage was unfortunate, but it wasn’t the reason that Phillips briefly second-guessed his decision.

“When I first got it,” he recalled, “it was ‘what am I buying a four-door boat for?’ I grew up in the muscle era and I’m thinking my buddies are going to look at me (and ask) ‘What are you driving an old man’s boat for?’”

Fortunately, that was as far as it went, but a much more important concern for Phillips was that while he was committed to the Chrysler’s restoration, his experience with such projects was limited. That was where a friend, Mike Wright, stepped in to help.

“He’s been a car guy his whole life,” Phillips explained. “If I get a car, it’s ‘Hey, bring it over. Come winter, we’ll work on it.’ I didn’t want to wait until winter. Every time I’d mention it to him, he’d say ‘just wait, we’ll get it’ and deep down, I’m saying ‘I want to do it now.’”

Finally, Phillips could no longer resist and started in on the basics by removing trim, the hood and the trunk lid for access and then stripping the body. In doing so, he discovered that there were no nightmares, although the sheet metal near the radiator was rusted and there was evidence of long-ago repairs to the lower quarter panels and the heels, two known problem areas on Chrysler products of the time. The door bottoms and the floors in both the passenger compartment and the trunk—areas that need to be inspected as carefully as the quarters and heels—proved to be undamaged.

“(Wright) said it was a good solid car to work on without a lot of rust,” Phillips continued, “and that was his biggest concern. Probably the worst part of the whole car was the rocker panels.”

The rockers were repaired and he said that Wright felt that the old repairs had been done well enough that they needed only some minor touch up before he painted the car. That was important, he said, since good sheet metal and trim for the New Yorker are difficult to find and expensive to purchase.

No Buyer’s Remorse, But…

“If I had it to do over again, I still would buy this car,” he said. “But I would’ve gotten under it to see whether the floor pans and the rocker panels were rotted, especially with the rarity of the car.

“If it had been a car where you could buy reproductions, it wouldn’t have mattered, but with this car, you can’t buy reproductions. …Stuff that you have to replace, can you replace it?”

Being certain that the car is as complete and solid as possible will minimize some restoration headaches, but after that comes the condition of the brightwork. The car wears a lot of it—much is specific to the New Yorker—and plating and straightening will not be cheap. Even the pieces that need nothing more than buffing can end up testing a restorer’s resolve.

One last red flag can appear when it comes to a 1956 New Yorker, and that involves the engine. It’s not that the 354 hemi is known for any particular weakness or problem, but it is, after all, a hemi. Many of the first-generation hemis—the 331, 354 and 392—found their way into dragsters, so in a worst case scenario where a restoration project’s engine is missing or not realistically rebuildable, locating a replacement might require more than a few quick telephone calls.

To make matters worse, not all of the hemi-powered Chryslers were as lucky as the featured New Yorker during the time period when they were merely cheap used cars. Many of those that didn’t lose their engines were driven hard until they were destroyed.

The hemis aren’t delicate engines and it takes a lot to damage one, but if it happens, the solution can become formidable and costly.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

On the other hand, that doesn’t mean hemis shouldn’t be driven. Phillips has taken the approach with his Chrysler that most restorers follow…he began with short local trips and gradually moved up to a few hundred miles at a time.

Driving it is one of the reasons that he hasn’t yet given the car such finishing touches as re-plating the bumpers, but that apparently doesn’t make it any less noticeable on the road.

Sometimes, though, the New Yorker’s rarity can create odd situations, as he learned when he stopped on his way to a show. Another vintage car followed him into a rest area, where its driver asked whether he could follow him to the event.

“I said ‘Yeah,’” Phillips recalled, “and he said, ‘I thought I was following a ’57 Chevy because of the back end, until I got closer and saw it was a Chrysler.’”

A straight-on view of the rear from a long distance would be about the only way to make that mistake, as the two cars share few design cues beyond fins that are vertical and narrow.

There’s no way, though, to know what another driver thought he was seeing when he passed the New Yorker as Phillips and I waited in it for a traffic light to change. Phillips said that his car is a head-turner and it certainly proved true at that intersection.

“I guess any old car; you’re going to look at it,” he laughed, “but this one, it does look cool.”

He was right, but driving the Chrysler is much cooler. We switched positions just across that intersection and it struck me that an average driver inexperienced with anything but modern cars could be briefly stumped; pushing a button to go from neutral to drive is one thing and twisting a substantial handle to release the parking brake is another. The transmission lacks the “park” position that some drivers today rely on in place of the brake, so figuring out all of that could be interesting.

Once he had the car underway, though, he’d quickly forget his embarrassment at trying to make it move because it’s so easy and comfortable to drive. The lack of an outside mirror requires some adjusting, but that’s not anything unique to the Chrysler and, more importantly, the windshield seems low and eliminates the sitting-in-the-parlor feeling you experience in the interiors of some of the car’s ancestors and contemporary competitors.

The driving position is right, with the steering wheel perfect for a long trip, the seat high enough to provide all-day support and an excellent view ahead. The steering and brakes, not surprisingly, quickly remind the driver that the New Yorker is 53 years old, but with that in mind, there’s little about which to complain.

Beyond all of that, the car has no body rattles and while that’s attributable to a number of factors such as low mileage and general condition, there’s also the fact that it’s a four-door post. A two-door or a convertible would be more desirable from the collector’s point of view, but it probably wouldn’t be as quiet and certainly wouldn’t run any better than a sedan. And the feature car has little to apologize for, thanks to that hemi.

At about 40 miles per hour, Phillips told me to step down hard and when I did, the 4100-lb. New Yorker squatted and literally acted as if it had been launched. We were on a road where that kind of driving isn’t smart—especially in a car that Phillips said wasn’t “made to go around corners fast”—so I backed down pretty quickly and I’ll only say that we might have exceeded the speed limit briefly. The Chrysler had much more to go and Phillips said that he’s driven it considerably faster several times on highways.

“Get past the kickdown,” he said, “and people don’t realize what happens.”

Some probably do realize; they’re the ones who see the car at shows and tell him that he should pull the engine and drop it into a street rod. That’s not going to happen and while the hemi is a big part of the New Yorker’s personality, it’s still just part of a package where everything works well together. Other cars might be faster or sound better or might be more comfortable. But taken as a whole, the New Yorker provides the perfect excuse to drive really far.

Anchorage and Rio de Janeiro immediately come to mind.