1954 Kaiser Manhattan

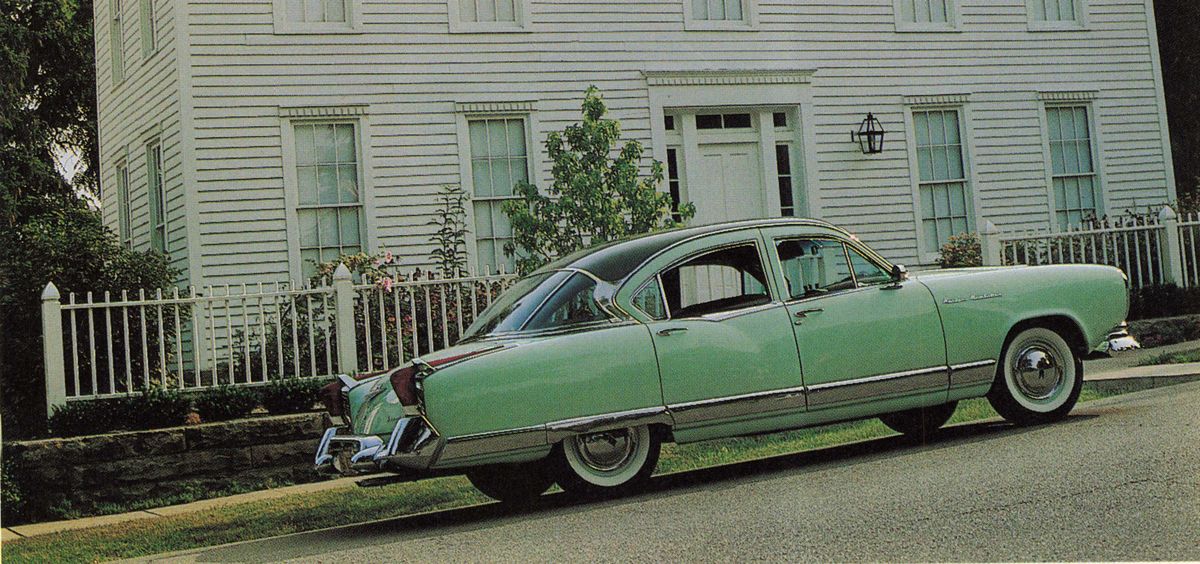

If styling alone sold cars, the 1954 Kaiser Manhattan might’v been a smash hit. Dutch Darrin, the famous designer of custom bodied Packards and other great classics, penned the basic shape that debuted in mid-1950 as “Anatomic Design.” Those Kaisers featured steeply raked windshields, acres of glass and a low beltline that wouldn’t be matched until the Forward Look Mopars of 1957.

The body was retained for 1954, but Buck Rogers details were added. The jet intake grille and headlights were a crib from Buick’s XP-300 show car. Safety-Glo taillights formed fully-illuminated fins atop the rear fenders. The new three-piece wraparound rear window was in sync with the latest trends, too.

None of this mattered at the time. Kaiser was on the ropes in 1954 with sales of just 8539 cars. After barely 200 domestic sales in 1955, Kaiser automobiles retreated to Argentina, where they were built until 1962. Experts offer a number of opinions for the Kaiser’s demise: no V-8 engine, no convertible or station wagon models and too expensive are among the reasons most often given.

Members of the Kaiser-Frazer Owners Club today feel no need to make excuses for their cars. The club holds an annual week-long convention that usually draws around 100 cars and 500 people, with this year’s event planned for July 14-18 in York, Pennsylvania. Fred Walker, chief judge for the club and a Kaiser parts dealer who has restored 40 to 50 cars, says very few of the show vehicles are trailered. Often 20 or more will have driven more than 1000 miles to attend the show.

Don Pribble, owner of our featured 1954 Manhattan (nicknamed Edgar), has rolled up 4000 miles in the past three years. “The farthest I’ve had it was to Corbin, Kentucky, about 1000 miles round trip. It performed flawlessly, didn’t even burp,” Pribble says. Edgar carries a sign: “If you see this Kaiser on a trailer, call 911 because it’s been stolen!”

Built for the Road

From 1947 to 1955, Kaiser relied on a long-stroke Continental 226.2-cubic inch flathead six-cylinder for power. It was a smooth and reliable engine. Walker traces the history of this motor:

“When Kaiser-Frazer began production,” Walker says, “Continental couldn’t supply them fast enough to keep up with the production, so Kaiser entered into an agreement to build the engine themselves. About late 49 or early ’50, Kaiser bought the rights from Continental. They modified the engine beginning with the 3."

Most changes concentrated on the engine’s weakest point, the exhaust valves which had a tendency to burn early. Mushroom tappets (where the foot is larger than the body) were installed, and for ’54 the valves got roto caps which spun the valves slightly with each stroke, evening wear and helping them to last about five times longer.

Kaiser’s six was the smallest motor in its medium-price class, smaller than even Chevy and Ford engines. The company had no extra money to build a V-8, so for ’54 they turned to a McCulloch centrifugal supercharger. Standard on Manhattan models, this upped horsepower from 118 to 140. However, the blowers developed a poor reputation.

Walker says, “I think the biggest problem was not that the supercharger gave problems, but finding someone in that era who knew how to work on it. For many people, if the supercharger became noisy or began to act up, they disconnected the belt.” Walker, a former Kaiser employee, bought his 54 Manhattan new. It has 169,000 miles on it and the blower still works fine.

The McCulloch unit was used on Fords and Studebakers later in the decade and is common in the aerospace industry even today, so parts and technical expertise are available. However, Walker emphasizes that rebuilding it is not for the average home restorer.

Since a professional supercharger rebuild can run $500, Pribble is one of many Kaiser owners who just does without. He removed the supercharger from his car and substituted the two-barrel carburetor and air cleaner from a ’53 Kaiser because that carb was designed to operate without a supercharger. The unblown Kaiser is a bit sluggish, but adequate for relaxed highway cruising.

The only other mechanical component that’s a bugaboo is the power steering on some °54 and 755 Kaisers. The entire steering mechanism was redesigned for power assist, but the Monroe linkage booster was actually only installed on about 700 cars. Thus non-assisted cars have discouragingly stiff steering, and parts for the booster on the few Kaisers that have it are scarce. Walker says the late-’50s Ramblers are the only other cars he’s aware of which used this same system and could be used for parts interchange.

Other mechanical components are reliable, standard industry parts. The three-speed transmission and overdrive is a Borg-Warner unit. HydraMatic transmissions were supplied by General Motors and the rear axle is a Spicer.

Walker and Pribble both claim most mechanical parts are available through auto parts stores like NAPA, although you'll need a helpful clerk to look them up. Walker warns you should deal with Kaiser experts for the special tappets. Major suppliers list them, but usually deliver the incompatible tappets for the nonKaiser Continental engine.

Invasion of the Body Patchers

Unlike many orphaned makes, trim for Kaisers is not a big problem. Pribble says most of the bright work is stainless steel, except the bumpers, horsecollar headlights, taillights and door handles. He repaired and polished all of his stainless himself.

If the trim is beyond salvage, Walker’s Auto Pride sells all five parts of the scooped grille, for instance, or the four separate pieces of the rear bumper. All are NOS parts. Walker also sells rockers and floor pans, and says used sheetmetal is available.

Pribble did all the bodywork and painting on his ’54 Kaiser himself. He describes his metal-working method: “After I’ve removed 99.99 percent of the rust with an electric steel brush, I always cover what’s left with POR15. Then I will normally put a plate on, using 16- or 18-gauge sheetmetal if it’s on the side, 14-gauge if it’s in the floor.”

Because moisture is the enemy, Pribble was careful to leave no space where it could gather and be conducive to rust. When he patched the floorboards, he cut two metal plates — one for top and one for bottom. He then sandwiched undercoating between them to fill the hole and squeezed all the air pockets out before riveting them in place.

To get the patches flush with the body, Pribble used a special Eastwood Co. tool called a panel flanger to indent the edges of the hole about /o-inch. He then welded or riveted the patch in place. Another Eastwood tool, dimpling pliers, sunk the rivet heads so he only had to grind off about 20 percent before applying the body filler.

Pribble gets a bit hot when other restorers dismiss body fillers like Bon do as amateur stuff. He says, “Dammit, there’s nothing wrong with Bondo. It'll last longer than any metal on the brand-new ’97 Cadillacs, but you’ve got to prepare the metal right. I’ve done a lot of cars for years and years and I have never yet had a bit of Bondo come loose.”

Finally, Pribble went over the Kaiser with DuPont primer and Centari enamel. He says it’s difficult to get a really good paint job working under florescent lights because small flaws don’t show up well in the soft lighting. He rolled the car out each. evening and inspected it with the sun close to the horizon. When he viewed the surface from an angle almost parallel to the sheetmetal, shadows cast by dimples and high spots were obvious. Pribble says shining a really bright incandescent floor light parallel to the surface produces a similar effect.

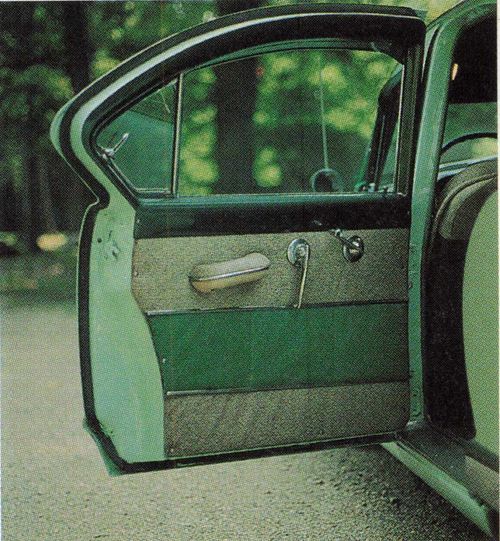

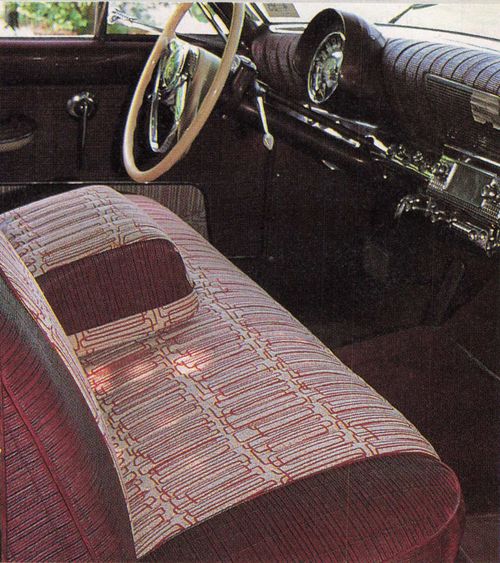

Mystery Upholstery Pribble was fortunate that most of the interior of his car was in good shape. Kaiser’s fabric-color specialist Carleton Spencer created beautiful, but unusual, combinations of fabric and vinyl for the Manhattans. Generally these materials held up well, but Walker says exact replacements for most of them are simply not available today.

The only flaw in Edgar’s interior ' was a dark green velour-like fabric on the seats that was very worn. Pribble’s upholsterer, Bob Langdon, located a very close match for the original material and stitched it into place, leaving the rest of the interior intact.

Walker says the Kaiser-Frazer Club has a realistic attitude toward judging interiors. Kaisers with perfect original interiors lose no_ points, while slightly flawed originals get docked one point and rough originals (those with a rip or two in the upholstery) lose two. A restored interior that perfectly matches the original doesn’t lose any points, while restored interiors that are a close match to the original materials lose two points and incorrect interiors in lesser condition lose four points. The club uses a 200-point scale for the whole car.

Buying Time

Obviously, good original upholstery is a major concern when looking to buy a Kaiser. Walker says it’s fairly common for the interior vinyl to still be in decent shape because of the strength of the material. The fabric inserts tend to be more worn. Walker suggests a few other things to check as well. The bushing on the center idler arm of the front suspension is often worn, but this is easy to replace. A compression test will reveal any problems with the engine’s exhaust valves. Walker says that a standard rebuild with roto caps and new stellite valves to handle unleaded gas seems to fix any valve problems.

For superchargers (all 54 and ’55 Manhattans were supercharged) Walker suggests, “If it turns freely and doesn’t make any noise, chances are it's operating. If it turns but makes a nasty growling noise, it probably needs a bearing-race kit, which is available for about $190. Then you need to get gaskets and someone who knows what they’re doing to work on it.” (Removing the supercharger costs two judging points.)

Rust shows up in four different places on Anatomic Kaisers. The rear fenders go bad above the wheel wells, and the rocker panels also rust. If there’s a problem with the front fenders, it’s usually at the vertical seam where they join the body. Finally, the front corners of the floorboards often rust where they join the cowl.

One big advantage for restorers is the Kaiser-Frazer Club’s $75,000 manufacturing fund. New members are asked to make a one-time $10 donation. The fund is used to finance the manufacture of rare parts to make them available at reasonable prices. Walker says the club has successfully reproduced items including rocker panels, steering wheels, floor mats and windshields.

Value guides list Manhattan sedans ranging from $1000 for a total project car to more than $10,000 for a number-one-condition vehicle. Walker says these values are a bit low; four-door sedans sell for as much as $15,000 and less common models such as two-door Manhattans, °51 and ’52 coupes, Dragons and ‘Travelers (a combination sedan/station wagon) can go for $20,000 and up in exceptional condition. Thus, folks who start with a complete car and are able to do the work themselves generally won’t put more into the project than it’s worth.

Plus, the end result is something out-of-the-ordinary, a car that’s fun to drive and fun to show. Pribble gets more than his share of attention even at local events, though many younger people have no idea what they’re seeing. One woman, for instance, was sure that Kaiser was a

German car. Others compare his ’54 Manhattan to a modern Chevy Caprice ... except the Kaiser looks better. Pribble proudly sums it up, “For a car pushing 50 years old, I think it does pretty well for itself.”

Gold Medal Kaiser

While any Kaiser is an uncommon prize for collectors, several rare models are especially coveted. One of the top prizes is the 1953 Dragon. Kaiser initially offered Dragon trim options on its Deluxe models in late 1950 and 1951. However, it was 1953 when the Dragon name was revived and the auto became a separate model. Priced in Cadillac territory at $3924, the Dragon was loaded with special trim and features. Only 1277 were built and approximately 50 restored models exist today.

Often these cars are referred to as Golden Dragons because of the conSpicuous gold-plated trim used on the hood, trunk and fender script. Another unique feature of the Dragon models were roofs covered in a heavy “Bambu” vinyl. The same material was also applied on the seats and dash. A few of the standard features were: Hydra-Matic transmission, tinted glass, radio with rear speaker, power steering and whitewall tires. Leonard Berger of Charlotte, North Carolina, bought this Dragon four years ago and restored it with the help of friends. He says the restorations are basically the same as a Kaiser Manhattan. All the trim, except for the Dragon fender script, is shared with less expensive Kaisers; 24-carat gold plating is the notable, but only, difference. Applying new gold plate cost Berger $550, while re-plating the remainder of the trim totaled $2000.

When Berger purchased the car he says the interior “was unbelievably nice for a car that old.” Some fabric was worn, but a bolt of the original cloth came with the car. That stroke of good fortune allowed Berger to replace the worn sections with authentic material. This fabric, called Laguna cloth, was designed specifically for the Dragon and features a pattern of overlapping rectangular shapes.

The Bambu vinyl on the roof and in the interior is extraordinarily tough and has weathered the years well. Some areas had faded, but otherwise no damage occurred. Berger took care of the faded areas by covering the entire roof with PPG dye sprayed on by his painter. Replacement vinyl for the roof or interior is difficult to locate.

The optional wire wheels are the same style that was used on Chryslers of that vintage. The Chrysler models had spinner hubcaps, while the Kaiser used Henry J hubcaps mounted via a spring clamp on the back.

Some details are recognized only by Kaiser experts. According to Berger, “Nobody knows why, but the cap that goes down over the spark plug is different than those used on the Manhattans. They call it bumblebee wiring because of the shape.” Replacements for these speCial wires aren't available, so Berger drives with modern wires and only puts on the bumblebees for car shows.