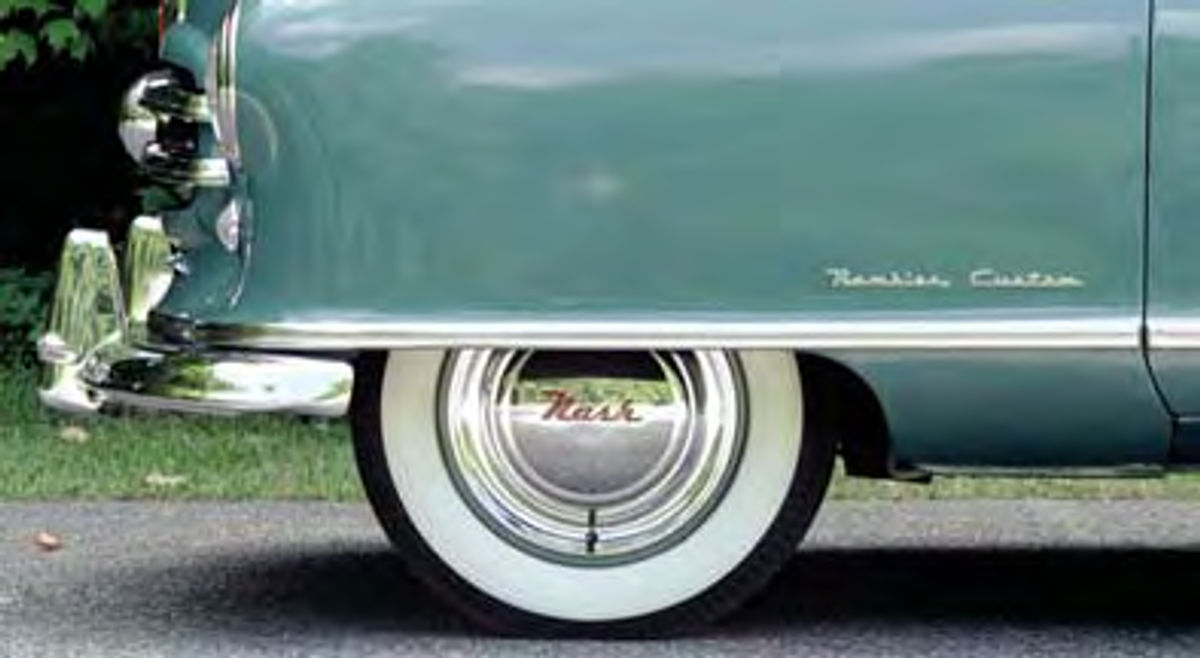

1952 Nash Rambler

Of all the offerings from the smaller automotive companies following World War II, the only passenger car to enjoy real success came not from a colorful mechanical genius or a flamboyant salesman, but from an oldline manufacturer. Despite their best efforts, Playboy, Tucker, Kaiser and the others just couldn’t make it; Rambler, on the other hand, took off smoothly and went on to a long and mostly happy life.

In hindsight, it’s clear that a new car from an established automaker could achieve what eluded the upstarts, especially when the established automaker was Nash. The company went back 48 years when it introduced the Rambler in 1950 and reached into its earliest history for that name. Production models of the original Rambler had been built from 1902 into 1913 by Thomas B. Jeffery Co., which Charles Nash—an ex-General Motors president—purchased in 1916.

In many circles, Nash Motors really doesn’t receive the credit it deserves, although the Classic Car Club of America lists several Nashes as Full Classics, and the company survived with Hudson as American Motors, the last Independent. Some of its cars are, admittedly, on the unconventional side, and probably the best-known examples of that trait are the Airflytes. Introduced for 1949 as Nash’s first new postwar cars, they represented a serious and successful effort to improve aerodynamics with a slippery fastback shape, smooth surfaces and odd but effective details such as minimal wheelwells.

The Airflyte design made Nashes very difficult to overlook on a busy street and it gave Nash just under 130,000 sales in its first year. For an Independent, that wasn’t a bad showing at all, but Nash knew it was no threat to the Big Three.

George Mason, president and chairman of the company, had been with Nash since 1937 and understood the challenge of going up against competitors that could produce between 500,000 and 1.2 million cars each to Nash’s 130,000. And although nobody used the phrase at the time, he also understood what amounted to niche marketing; by aiming at a target ignored by GM, Ford and Chrysler, Nash would have that market to itself. Since Mason believed in small cars—as did George Romney, who arrived in 1948 and would become Mason’s successor—Nash had been working in that direction for several years and its work paid off in 1950.

Small, But Not Cheap

The 100-inch-wheelbase Rambler was compact without being tiny or, as some earlier attempts at small cars had been, ridiculous. It weighed in at 2430 pounds and its flathead six, rated at 82 horsepower, provided performance that could almost be called spirited.

The Rambler’s styling and design left no doubt that it was a Nash. The grille used horizontal bars in place of the fullsize Nashes’ checkerboard, but nearly everything else seemed to be a miniature of what the larger cars wore. The sides were smooth, the wheel wells were almost non-existent and there was a general plumpness about the Rambler that mimicked other Nash products.

That Nash chose to launch the Rambler only as a convertible suggests much about the thinking behind it. Clearly, Nash had determined that it was not about to build a mere bare bones economy car and its list price reflected that; for not much more than the $1800 that would buy a Rambler, a customer’s choices included Chevy, Plymouth and Ford convertibles as well as a Dodge roadster. Unlike the Rambler, every one of them was a full-size car, so Nash was obviously positioning the new model as a quality car that simply wasn’t large. That meant it couldn’t be a stripper, so for his money, Rambler gave the customer features such as a radio, a heater, an electric clock and an electric convertible top.

Just as the Airflyte styling remains a signature feature on Nashes of that time, the uncommon convertible top belongs to the Rambler. It wasn’t the first car or the last to use a top that opened by sliding on fixed side rails, but it’s certainly the most widely known example in the United States.

Superman Influenced This Purchase

The fact that Daily Planet reporter Lois Lane drove a Rambler convertible in the original “Superman” television series helped to ensure broad exposure for the car even years later, thanks to the magic of reruns. That played at least a minor role in Mark Lehman’s decision to buy the 1952 convertible featured here.

“I always did like the ‘Superman’ thing,” he laughed. “I thought that was neat.”

His interest in Nashes generally went deeper, though, and he already owned two Ramblers when he learned in 2005 that the feature car was available. Its owner had died, and his family had offered it to a Nash parts vendor, Maynard Keller, who looked at the Rambler and then passed on the information. Lehman decided to check it for himself.

“The owner’s son was there,” Lehman recalled, “and he showed me the car. He had it running, and once I saw it, I knew I wanted it.” It was a good choice, as its original owner had bought the Rambler as a leftover in 1953 at Park Avenue Motors in Quakertown, Pennsylvania, less than two hours from Lehman’s home in Pottsville.

“He was only 17 when he bought the car,” Lehman said. “He went in the service and I don’t know if he sold it or gave it to his sister, and she had it until ’83. He got it back off his sister, and that’s when he and his son did the work to it. They restored it and he died in the fall of ’94.”

In essence, the Rambler wasn’t exactly a one-owner car before Lehman bought it, but it had never left its family. The original purchaser’s decision to reacquire and restore it speaks volumes about his attachment to the car, but it’s not all that odd; Ramblers like Lehman’s were wellliked and appreciated in their time. True’s “Automobile Yearbook of 1952” cites two examples of satisfied owners, beginning with one who had traded an MG and found that the Rambler “corners nearly as well as his MG, has almost as much speed and 50 times the room.” The other owner was “Bill France, president of NASCAR...(who) uses a Rambler station wagon exclusively when he is running a large race. With the Rambler, he can dart in and out among the race cars when trouble looms yet the car is big enough to carry all his racing equipment.”

The feature car probably led a life less exciting than either of those before Lehman bought it, but that almost changed as he was taking ownership. The plan, he said, had been to drive it to Keller’s garage, where it would remain until he could trailer it home.

“It was a January day,” Lehman said, “but there was no snow on the ground. We got all done with the title work, and I looked and I could see it starting to snow. It was starting to stick to the ground, and here I am with this car with 20-year-old bias ply tires.

“I had to drive probably about five miles, and the road was getting slippery by the time I got to Maynard’s. I was spinning the tires.”

It’s Been a Reliable Ride

He agreed that the snowy encounter might have been the only time in its life that the Rambler spun its tires, but his story did raise the question of how well it dealt with slippery roads.

“Not too bad,” Lehman said, “I guess maybe because it wasn’t overpowered.” If so, it’s not because the engine needed help, as it was rebuilt during the car’s 1983 restoration. Lehman believes that the Rambler has covered about 60,000 miles—a replacement odometer reads lower—and said that it’s had only a few problems in the time he’s owned it.

The brakes had been rebuilt after the restoration, he said, but before making a trip to Detroit with the car, he decided to inspect the system.

“I pulled back the cups,” he said, “and everything looked like brand-new on the brakes. I couldn’t believe it.

“I put a new master cylinder on since then because it was starting to leak, but other than that, I couldn’t believe how good the brakes were. They’ve been fine ever since.”

A new exhaust installed by the previous owner didn’t hold up as well and that was replaced last summer. Lehman also replaced the floor-mounted starter switch, which was worn badly enough that it sometimes refused to be engaged. “It was getting to the point where it would start every other time,” he said.

That was the extent of the mechanical work on the Rambler, and the body needed nothing beyond some serious detailing, but Lehman said that the interior and trim required attention.

“I redid the interior,” he said. “I had new cloth sewed in and I had the armrests rebuilt because they were collapsed.” The door panels had already been replaced and some of the interior is original, but suppliers were able to match the various materials so that the necessary replacements could be made. The back seat had held up well and was intact but was badly stained and had several small holes.

The front seat was another matter, as its cushion had lost all of its upholstery and was not much more than a seat cover on foam padding.

Look Closely at the Trim and Floors

Fortunately, the interior plastic parts had survived in good condition, but then came the exterior stainless steel trim.

“It’s really hard to find new stainless for that,” Lehman said. “The door (pieces) are like hen’s teeth to find. They used them on all the two-doors up to ’55, but they’re still not easy to find.”

Although none of it was missing, one piece had been damaged badly. Lehman was able to replace it with a piece that a friend had removed while restoring another Rambler, and he dealt with several others that had relatively minor damage.

“There were a couple of little dings,” he explained. “I worked them out and did them on the buffer. Some of them aren’t perfect, but they look a heck of a lot better than they did.”

The stainless trim wouldn’t disable a car by its absence, but it is something to look at when considering a Rambler such as this one. There are other points, though, and since the Rambler is a unitbody car, identifying its most critical potential problem shouldn’t require a lot of work.

“Floor rot,” Lehman said, “No. 1. That’s the major thing.

“The first thing I do is crawl under and look at what I call the filler pans, those triangular pans in the front that go next to the frame rails, because that’s the first thing that rots through.”

The feature car had had only some minor repairs made to the floor during its restoration, but it’s impossible to overemphasize the importance of looking for rust damage on a Rambler. When Lehman talks about crawling under the car to inspect it, he’s right; the apparent condition of the body isn’t a reliable indicator of the floorpan or other structural areas, such as suspension mounts.

If it’s a convertible, he said, completeness of the top and the mechanism is extremely important, but there’s another consideration that’s likely to come up later, when the car is being restored. He and his brother, Paul, know about that.

“He has a ’51 Rambler convertible,” Lehman said. “We tried to put his together by going by the service book and it’s pretty detailed, but we couldn’t figure it out.”

The top uses a reversible electric motor to operate steel cables that must be wound perfectly. Lehman said that even with the manual, they were unable to make everything work as it should. The solution was simple.

“We couldn’t get it right so we ended up looking at mine,” Lehman recalled. “We had to take the panel out of the back and we went by that and actually got it working pretty well.”

Beyond the mechanism, the top is complicated in its operation. Lehman said that canvas straps tie the bows together and that when one of the straps on his car ripped, he was able to find an original repair kit. It was, he said, pure luck. “Something like that would probably be nearly impossible to get,” he said. “So I probably would’ve had to fabricate something for it.”

As on any convertible, a restoration project probably will require the top’s replacement. Lehman said that he and his brother installed a new top on the 1951 Rambler, and it wasn’t especially difficult. The top on his own car operates as it should and he has no reason to expect problems with it, but he said that his brother has an extra motor, something which, apparently, is a unique piece with no interchange.

That’s not the case for every part on the car, of course, as Lehman said there’s some interchange among the stainless steel trim pieces even if they’re not always easily found. Door stainless, he said, is identical through 1955, but fender trim is different year to year. Parking lights interchange with those of Nash-Healeys (which almost certainly is more important to Nash-Healey owners than to Rambler owners) and certain other Ramblers. Even taillights have some interchange, but the best news is in the drivetrain.

A Roomy Little Car

The flathead six was a Nash standard for years and went on to become an American Motors standard. Like most engines, it evolved, and although it never really became what might be called a performance engine, finding a replacement shouldn’t be too difficult. It might not even be necessary, as Lehman said they’re dependable engines with no known major problems.

He did, however, cite a few quirks. Fans on earlier engines sometimes cease, he said, recalling a 1940 Nash whose fan destroyed its radiator. The side-mounted water pump is rebuildable, but his statement that doing so “tests your religion” suggests that it’s not a simple task.

“The valves on them can be a little tricky to adjust,” he explained, “because there’s not much room. On the bigger car, the Statesman, it’s not bad. On my other car, the valves are really quiet. On this one, the valves are noisy. I’m sure they need to be adjusted and, of course, they tell you to do them hot. I don’t think you could ever do them hot unless you want to have third-degree burns.

“One thing I can tell you about these engines is that when they sit a long time, start them up and they smoke like you wouldn’t believe. And right away, people are saying, ‘Oh, this needs to be rebuilt,’ but once you run them, they’re fine. When I got that ’54, it hadn’t been run in a couple of years.

“We started it up and the whole garage was filled with smoke, but I’ve been driving it, and now; it’s fine.”

The feature car didn’t smoke when he bought it, he said, meaning that it must have been driven fairly regularly. That makes sense; the Rambler is a car to be enjoyed rather than one to be endured. Thanks to its size, the first question is its economy, and Lehman said that an overdrive-equipped example returned 32.09 miles per gallon in a Mobilgas Economy Run, while his is good for at least 25 mpg in normal highway driving.

The car easily keeps up with Interstate traffic, he said, but how does it handle in-town driving?

Do the skirted front wheels impact the turning radius?

“It’s big,” Lehman said. “It takes a little getting used to. You might have to back up a few times.”

A U-turn on the average street would be tough, but the Rambler easily negotiates a drive-through lane that goes around a fast food restaurant. The real problem is in parking it.

“Sometimes,” Lehman said, “just to pull into a parking space, you’ve got to take a little more of a swing.”

That’s not much of a disaster, and it’s handily offset by the Rambler’s positive attributes, beginning with its comfort.

“We took it out to Detroit and it wasn’t bad,” Lehman said. “The upholstery’s padded enough. You have enough legroom... “I love the brochure that shows five people (riding in the car).

“They have three in the front and the one is sitting sideways, talking to the other person.

“But then we actually had six people in one of these one time.”

Six passengers undoubtedly probed the limits, but as he said, it does have ample legroom and comfortable seats. Remember, Nash was aiming for a nicely appointed car that was small—it wasn’t trying to build a 1950s version of the low-budget Yugo. Adding in its decent brakes, good shifter and other pluses therefore gives it strong appeal as an entry level collector car.

“I think most Ramblers are,” Lehman observed. “They’re fairly dependable, I’d say they’re not terribly expensive to buy, they’re not really hard to work on for somebody who does their own mechanics. Parts aren’t bad or hard to find.”

He might be just a little biased, as his interest in Nash dates back a few decades and he takes credit with his brother for having convinced their father to buy American Motors cars. He explained that his brother was not quite old enough to drive when he spotted a 1956 Statesman and asked his parents to buy it for his first car.

“He ended up not getting that car, then one day, he came home from school and my dad had a Metropolitan sitting in the driveway,” Lehman said. “So that’s kind of what got us into it, and I was always the little brother. I’d be in the backseat of the Metropolitan. We had three of them. That was his first car, then he got a nicer, low mileage one later, and then I got one.” His own Metropolitan, though, was not his first car. “Actually,” he said, “my first car was a Studebaker. When I learned to drive, I bought a ’61 Lark and then I traded it. I traded it even-up for the Metropolitan.”