Here Come the Doodlebugs

The sight of one doodlebug can make Model A fans dyspeptic and if that reaction is understandable, it’s also not always appropriate. “No,” said Ron Oakley, the Binghamton,

New York, owner of a 1928 Ford doodlebug. “No cutting up. That’s one thing a lot of these car clubs think, that we took a Model A. We didn’t. Nobody did that here. That thing was sitting in a gas station for years, it worked. You could duplicate one, and you could probably build one out of parts. But these are originals.”

When he said “Nobody did that here,” he was talking about the Doodlebug Club of Franklin in Franklin, New York. “Doodlebug” might also need an explanation—it’s grown obscure in automotive history since its 1920s-to- 1940s heyday—and a 1938 Sears catalog provided a good account.

“You can build your own farm tractor at low cost,” promised the description of Sears’ Thrifty Farm Tractor Unit. “Now you can transform your old Chevrolet or Ford into a practical tractor—quickly and economically. All you need to build a fine general purpose tractor is an old Model ‘T’ or Model ‘A’ Ford, or a 1926 to 1931 Chevrolet, and a Sears Thrifty Farmer Unit. With the auto body removed, you can quickly convert the old auto into a tractor that has the pulling power of two to four horses. The Thrifty Farmer will do practically every job that many of the regular-type tractors will do. The Thrifty Farmer attachment on the average used Ford or Chevrolet chassis has the speed and power to operate any of your horse- drawn tools. It works in any soil condition to work with horses and often works where horses cannot.”

The kits cost $93.50 for the Model T, $101.50 for the Model A and $106.50 for the Chevrolet. Affordable, but not cheap, as the figures in today’s dollars are $1565 for the Model A, $1704 for the T and $1788 for the Chevy. For his money, the purchaser received a half-ton package that included steel front wheels, cleated tractor wheels for the rear, a tractor-type seat, a subframe and a drawbar for implements.

Sears was not alone. The 1919 edition of The Model T Ford Car and Ford Farm Tractor described Acason’s chain-driven Aca-tractor kit as well as the Make-A-

Tractor conversion, emphasizing that the latter “can be fitted to other passenger cars as well.” A Model T, though, was a wise choice because “the power and reliability of the Ford engine make it possible to use this light chassis for much heavier work than you would imagine it capable of.”

There Was More Than One Approach to a Doodlebug

While less of a consideration in the Model T era than it would become during the Great Depression and World War II, an owner pondering a doodlebug knew that he would no longer have a car, but Knickerbocker Motors had the solution. A 1919 clipping headlined “pleasure car not lost in this tractor” explained that “at a time when the development of the country’s agricultural resources is of greatest import, the announcement of an attachment that will turn any one of the million-odd Fords in the country into an efficient tractor for all kinds of cultivation purposes is particularly significant and of great importance to the farmer. This device, which is called a Forma-Tractor, is simple in construction, but sufficiently rugged to stand the strain of work in the field and has the efficiency of a four-horse team... (It) is so adapted to his Ford that it can be attached and detached within less than 30 minutes and therefore will not deprive him of the use of his car as a pleasure vehicle or for carrying produce to market.”

Besides Knickerbocker, others such as Montgomery Ward and David Bradley also offered kits, but for those who couldn’t afford their cost or really didn’t need kits, plans were available. In the 1930s, Modern Mechanix published plans with the observation that “perhaps in your own backyard you have an old Model T Ford truck or passenger car that wasn’t worth a license tag.” The article described the result as a “Handy Henry,” one of the many nicknames for tractors built from cars or trucks. At the time it was reported that a Handy Henry could be built for as little as $20, a much more reasonable figure for a farmer of that era.

Tractors With a Mysterious Past

Both of Oakley’s doodlebugs are home- builts based on 1928 Fords and beyond that, things get sketchy. He bought the one shown here about seven years ago after seeing it in Franklin’s Memorial Day Parade. Its owner was a club member and provided the name of its previous owner in Unadilla, New York, but when Oakley called him, the trail became hard to follow.

“He couldn’t even remember the name of the guy he bought it from,” Oakley recalled. “He said it was somewhere south of Deposit, (New York), down around Shehawken, Pennsylvania. The guy he bought it from put that seat on it and that box on the back, and he redid the drawbar, too. He was using it around his property for things like hauling firewood.”

From there, the mystery gets better.

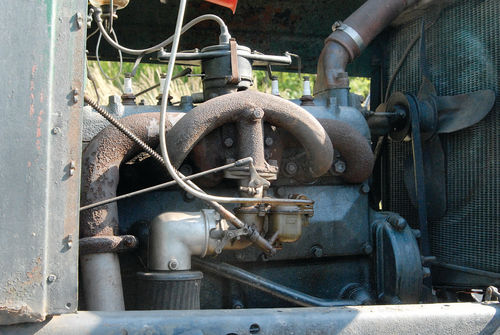

“It’s a 1928 Ford Model A, sort of,” Oakley explained. “They shortened the frame, took out the rear suspension and put a truck rear end in it. It’s a TT (truck) worm-drive rear with an AA four-speed transmission. I’m thinking it was a pickup truck, but I can’t verify it. There aren’t enough identifiable parts to say for sure, but it’s got a truck steering box. There were different headlights on it when I bought it and I put those headlights on it, but they’re not ’28, either. They’re ’30- ’31 headlights and the front bumper is not a ’28 bumper, it’s a ’30-’31 bumper. But it’s a doodlebug, so it’s kind of whatever-whatever...

“The other one was my first one and that’s also a ’28 Ford. That was made out of a two-door sedan, the guy told me. That’s got two transmissions and a truck rear end.”

Memoires of Past Doodlebug Days

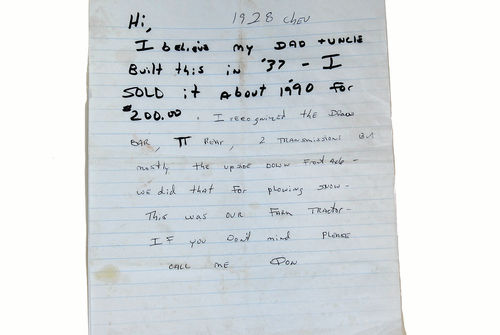

Oakley’s brother, Boots, bought his doodlebug in Geneva, New York, about eight years ago. It’s not quite as much of a mixture, but it’s a good example of working with what was available, as he said that the 1928 Chevrolet sedan was shortened, given a Model TT Ford rear and second transmission and its front axle installed upside down in 1937. He learned about it from the son of one of its builders.

“The father and the uncle went from farming to building houses,” Boots explained. “The first three foundations, he said, they did with the doodlebug and one of those scoops you walk behind a horse. Now, that had to be a project.”

He made the connection after a note left on the Chevy spoke of the front axle as a dead giveaway that it was indeed the same doodlebug that the builder’s son had sold in about 1990.

“I’ve talked to him on the phone,” Boots said. “I thought it was awfully interesting that the guy recognized it.”

Between that 1990 sale and the time he bought it, the owner in Geneva had acquired it at a farm auction and restored it to use. Boots heard about it from him at a swap meet, went to look at it and then brought it home to Tunnel, New York, a decision that probably has something to do with his memories of doodlebugs in regular operation. “The last working one?” he recalled. “My brother and I were young yet. We were around 15, probably, and a fellow was buzzing wood up with it. Off of a (doodlebug), he had a pulley, a flatbelt, running his buzz saw. He had a corner jacked up, just one side.

“These were used a lot for hay wagons,

too. I’ve got another one at home that a fellow built and that was the whole purpose of that. He had a 1500-acre farm and he used the doodlebug to pull hay back and forth because it was quicker, and it gave him a vehicle to run back to the house for lunch or whatever.”

Some Still Are Working Vehicles...

“I was using mine today in the woods,” said Ron Bauder, past president of the club. “I’ve got a little ’31. But I found out that once you load the trailer up with a lot of wood, the brakes aren’t so good. It’s still a Model A and you’re carrying a 600- or 800-pound load behind it, but it ended up that it was OK. I use mine a lot just around the house, moving things around.”

“I talked to a guy out in Spencer, New York,” Ron Oakley said. “I tried to buy a doodlebug from him and he said he’d been plowing his driveway with that for 50 years and it wasn’t for sale.”

Others Were Idled for Years...

As with other collector vehicles, not all doodlebugs are running or capable of running when found. Bauder’s Ford had worked at pulling lawn mowers on a golf course, but that was 45 years before he noticed it in the woods near Tuxedo, New York. He stopped to ask about it and that led to a return trip to look it over and negotiate the deal.

“The engine turned over,” Bauder recalled. “You could hold the belt tight and you could turn the engine. If the engine turns over, it’ll run, no question about it.”

He trailered it home to Treadwell, New York, where he disassembled it and tore down the engine for what amounted to minor work. Once back together, he said, it started easily and has now been running for about 10 years.

Things went less smoothly for Mel Ogden of Franklin when he found his 1929 Ford doodlebug in Coventry, New York, about 12 years ago. Like Ron Oakley’s Ford, its past is less than clear.

“It was a car, we think,” he said. “You never really know. It was cut down for a doodlebug back in the ’50s or late ’40s. The guy I got it from said that’s when he used it. They used it around the barn, moving stuff around. They used it for a hay rake.”

They also used it up—or believed they had—as the head had been removed from the engine. Leaving the doodlebug unprotected outside hadn’t been smart, so once it was in his garage, Ogden and a friend began working.

“The engine was rusty and ceased up,” Ogden explained. “We put a penetrating oil-automatic transmission fluid mixture in it and a friend of mine would come over. We put a jack on the crank in the front, a bumper jack so that there was constant pressure against it. He’d come over and take a block of wood that fit the cylinders and he’d take a hammer and hit it. He’d keep jarring the pistons and jarring it broke the pistons loose. We never put rings or anything in it. We just got it freed up and working. The valves, we got them freed. We did have to put a new head gasket on it, but the head wasn’t broken.”

Some Others Haven’t Survived...

That doesn’t clear up why Ogden’s doodlebug had been parked with the head removed, but it was lucky. It’s been running since then, which means it fared far better than another doodlebug Ogden remembers from the early 1960s.

“When I grew up,” he said, “our neighbors had doodlebugs that they used on the farm and I used to ride on them. They had an old Whippet that had a buck rake on it. When they were doing the haying, we’d go up and ride on the old buck rake. Run it all day, they would. They’re quite big, the buck rake part, and they used it to bring the hay in before they had the balers and stuff like that. We rode around on that as kids and that’s kind of what got me the interest, but that got junked. I tried to find it.”

Getting Involved With Doodlebugs

Obviously, others have had a better fate and Ogden spoke of his first doodlebug rescue. In 1998 a friend asked that he trailer one home from Morris, New York. Ogden, a founding member of the club, recalled his surprise that he’d found it and added that for a time, he and its owner were certain that it was the only doodlebug around.

“Then a couple other guys in Franklin saw it,” he continued, “and they knew where there was another one, sitting in the woods. Within a couple of months, we had about four of them come out of the woodwork and now, we’re still finding them. I’m going to say there are 20-some in the club right now. I haven’t counted lately.”

Editor’s note: And just where did that “Doodlebug” nickname originate? One the- ory is that it started with the David Bradley conversion kit. David Bradley...DB...Doodle- bug. But as with so many of the automotive tales from decades ago, it’s hard to tell what’s the truth and what’s a convenient myth. So, can any readers shed some light on this for us? And while you’re at it, why not share your favorite doodlebug stories as well.

The club’s membership requirements are uncomplicated. “I like doodlebugs” is the big part, Ron Oakley agreed, and the cutoff is 1950. Any make is acceptable.

“The Chevys and the Fords were the most common,” Ogden said. “There were Dodges and Chryslers, they used anything they had. They used their car until they couldn’t put it on the highway for one reason or another, then they’d put a truck rear end in it and make a homemade tractor out of it.”

“If you had to run out to pick up a wagon,” Ron Oakley said, “it was faster than hooking up a team of horses. And they were even faster than your tractor of the day. There are all kinds of stories about them and all kinds of different configurations because they were built to do a specific job like working on a potato farm or working on a dairy farm. The dairy farm version usually was used for hauling milk cans from the milking parlor out to the road, so it would have a platform box on the back like mine has. And they were used for haying, which didn’t require a lot of pulling power.

“The other one that I have, the one with the four-speed transmission behind the three-speed transmission with the two-speed rear end—you can do the math and it has all kinds of gearing—the guy said that in its day, it would bust sod with a double-bottom plow behind it, so it has some pulling power.”

You Need an Altered Perspective

It takes some thinking today to appreciate the wisdom of the doodlebug approach. During the Great Depression, few farmers could afford new tractors and during World War II, those who could afford them probably couldn’t find them.

“Factories were geared up to make war machines,” Boots Oakley noted. “You just couldn’t get tractors, but most everybody knew where there was an old car out behind the barn. Once you got the thing working, you could always switch motors. My brother read an article awhile back where a farm family was right in the middle of haying season and the doodlebug broke down. They took the motor out of their car, put it in their doodlebug, finished their haying and then took it out and put it back in the car.”

Some Are Easier Projects Than Others

A Model A- or Model T-based doodlebug clearly is the most practical today because of the support for at least some of the vehicle’s components.

“You can buy anything you need for a Model A,” Ron Oakley said, “and there are even hot rod parts for them. Because it’s readily fixable, I chose a Ford.

“But my brother has a ’28 Chevy with an overhead-valve four-cylinder and it’s been running for years. He had an electrical problem with it and it was a bad starter switch. I think that

was the only problem he’s ever had.”

By their very nature, doodlebugs often are built of pieces from a wide array of vehicles and other donors, thus creating problems. The rear end, the second transmission and other pieces might prove challenging and there’s also the matter of authenticity in restoration and repairs.

“They had no welders, no torches or anything like people have today to do that kind of work,” Boots Oakley observed. “They had to cut everything off with hacksaws, they had to drill holes in the frames and bolt them back together.”

“People built them just the way they wanted to for what they had to do,” Ogden said, “and that’s what we’ve tried to do, keep it that way.”

They Work...But Not as Hard as They Used To...

Whether restored or revived, a doodlebug is tough to enjoy if there’s nothing to do with it. Bauder pointed to those who use them for hauling firewood and Ron Oakley said that Ogden’s handles basic gardening work, but for a doodlebug today, life can be good.

“We go on rides,” he said. “Sometimes it’s off the road and sometimes we go out and do maybe a 20-mile loop on the back roads.”

The club participates in car shows, parades, tractor runs and other events.

“People who are say 40 and older know what it is,” Ogden observed, “but you get 40 and younger, yeah, they’re scratching their heads. ‘What are these things?’ We go to the vets’ home over in Oxford, New York. The car show had Corvettes and they had all the hot rods, but the old vets wanted to see these. They remember these things. Usually, if you’ve got gray hair, you might know what it is.” “We get the ‘I haven’t seen one of those in years’ routine,” Ron Oakley said. “A lot of people have stories about them; what they did with them, unique things about them, tech tips.” Sometimes, though, it doesn’t take anything as organized as an agricultural fair, car show or even a run to generate the slap-on-the-forehead reaction.

“People stop at my garage because I’ve got four or five of them around there all the time,” Ogden said. “They pull in and take pictures.”