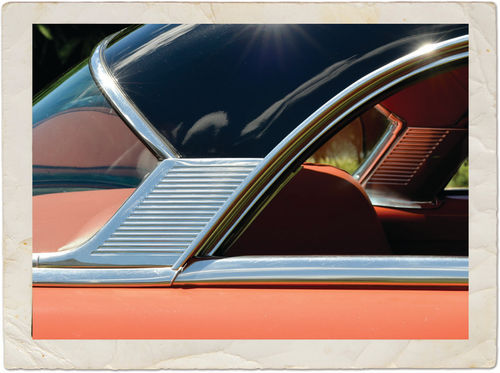

1953 Mercury Monterey

He’d Already Owned Several ’50s Mercs, So When This One Was Available, He Didn’t Hesitate.

The old cliché about there being no substitute for experience has a place when it comes to knowing that a car is the right car.

“I wanted a Mercury,” said Dick Leonard, whose 1953 Monterey is featured here. “I’d had ’51s, ’52s, ’53s, a ’55 and a ’57. Then I’d had other ones after that.”

He’s far from the only driver to recognize the car’s appeal, as Mercury has had its faithful believers since Ford launched it as a cleverly positioned model to fill what it perceived as a gap in its corporate range. At its 1939 introduction, Ford announced that “this year, a new car—the Mercury 8—joins the Ford-Lincoln family…fulfilling the desire of many motorists for a quality car priced between the Ford V-8 and the Lincoln-Zephyr V-12 and combining many virtues of each.”

The gap wasn’t merely something that Ford had imagined, as in its first model year of production, Mercury tallied about 60,000 sales of what was “a big, wide car, with exceptional room for passengers and luggage. Clean, flowing body lines are Lincoln-Zephyr inspired” and while that was true, it overlooked the fact that the new model also bore a clear resemblance to the 1939 Ford. Those not particularly attuned to cars might have assumed that the Mercury was nothing more than a re-trimmed version of its older sibling, but that wasn’t quite the case. The Mercury really was bigger with its 116-inch wheelbase topping Ford’s by four inches and there was, of course, a flathead V-8 under each car’s hood, where the Mercury also had the advantage. Its 239 edged out the Ford’s 90-horsepower 221 and Mercury made the most of the comparison when it boasted that “a new 95-horsepower V-type 8-cylinder engine assures brilliant, economical performance.”

Near a drawing of a formally dressed couple—a gown for her, a top hat for him—lounging in the exaggeratedly roomy rear seat, the ad noted the Mercury’s “exceptional width and room for passengers…luxurious appointments and upholstery, new soft seat construction, thorough scientific soundproofing” and “large luggage compartments,” all suggesting that a Mercury was a real step up from a Ford.

For those who still couldn’t quite see it, another ad got right to the point by stating that “the impressive size of the Mercury 8 is not an illusion” and cited the 116-inch wheelbase, 194-inch overall length and the sedan’s front and rear interior widths of 54 and 56 inches respectively. In case that led anyone to fear that a Mercury might be ponderously huge, a third ad offered the reassuring statement that “it is a wide, remarkably roomy car, but skillful design has made its bulk beautiful.”

Then World Events Got In the Way

Mercury was on its way to good times and when the mildly updated 1940 version arrived, the company was unable to resist some well-deserved bragging. “Introduced at last autumn’s motor shows,” advertising trumpeted, “the new Mercury 8 leaped in ninety days to a rank among the country’s ten best selling cars! Today its record is a proud one—sixty thousand owners in a single year—sixty thousand friends. It is a proved car.”

Other ads that year pushed economy and style, but 1941 brought a new look. On a wheelbase now measuring 118 inches, styling grew less elegant. The grille with its new sheetmetal divider was widened and less flowing, fenders were slightly boxier and the concealed running boards made the body seem less clean.

But 1942 brought “the new airplaneengineered Mercury 8.” The 239 was now up to 100 horsepower, the short-lived Liquamatic semi-automatic transmission had arrived and there was “new massive beauty” in the form of a wide two-level grille whose center split had almost disappeared.

This new Mercury, that the company said was “built tough and strong like Uncle Sam’s newest planes,” never had the chance to prove itself, however, as the opening of World War II cut short the 1942 model year and changed everything. The auto industry had been moving increasingly into defense production and early in 1942 it quit building civilian vehicles and made the transition complete.

Moving Into the Modern Marketplace

After the war’s end in 1945, the industry’s transition reversed itself and when the first civilian vehicles began rolling off the lines as 1946 models, they looked like the 1942 models with annual updates. They didn’t need to be much more than that because every car that could be built had a waiting buyer.

The war years had not been easy on home front vehicles and the need to replace them was real, but the automakers knew that their sellers’ market couldn’t go on indefinitely and so truly new cars began to appear.

Like many of its competitors, Ford Motor unveiled a 1949 range that couldn’t possibly be mistaken for the previous year’s models. Lincoln was the most dramatically changed as it gave up not only its prewar body, but also its V-12, the last passenger-car engine of its type from an American manufacturer. Ford came up with a look that was the essence of “slabsided” and one of the cleanest designs of its day while Mercury went for the whole effect as its advertising proclaimed…“it’s long! It’s low! It’s really massive!”

The first true postwar Mercury was not quite as slabsided as the Ford and was instead rounded enough to look much like a Lincoln. Its V-8 was now up to 110 horsepower from 255 cubic inches and Mercury described it as “a powerful new 8-cylinder, V-type engine with surprising economy.” That placed it in the middle of the company’s three passenger-car V-8s—Fords used a 100-horsepower 239 and Lincolns a 152-horsepower 337— which made perfect sense for the car that was in the middle of the company’s hierarchy, but there was a problem. All of those engines were flatheads, and General Motors had just announced the first modern V-8 engines available in its Cadillac and Oldsmobile lines. The GM engines used overhead valves and oversquare dimensions in which a piston’s stroke was shorter than its cylinder’s bore.

The advantages of the new GM V-8s were difficult to dispute and included higher revving, better breathing, potentially much-higher compression and two pluses that might not be apparent at first glance, a lower, lighter engine requiring less cooling. In Cadillac’s case, for example, the cooling system’s capacity went from 25 quarts in 1948 to 19 in 1949 at the same time that horsepower rose from 150 in the 346-cubic-inch flathead of 1948 to 160 in the 331-cubic-inch overhead-valve unit of 1949. If that doesn’t seem like much of a gain, consider that the same 331 was good for 210 horsepower just four years later. The future had arrived and comparable engines were soon being introduced by other manufacturers. Chrysler and Studebaker followed in 1951, DeSoto and Lincoln in 1952, Dodge in 1953 and Ford and Mercury in 1954.

A Flathead’s Fine With Him

As with the Cadillac engines, the improvement from Mercury’s last flathead V-8 to its first overhead-valve engine was eye-catching, to say the least, going from a 125-horsepower 255 to a 161-horsepower 256. It’s a difference that’s not important to Dick Leonard and he has a standard answer for those who can’t quite figure out the year of his car.

“A lot of them get confused,” he explained, “and say ‘is it a ’54?’ If they know the ’54, they wouldn’t even think about it because the taillights are entirely different and the grille is quite a bit different. What I always say is ‘no, it’s a ’53. It’s the last of the flatheads.’ Then that gets a lot of people.”

In a sense, it got him, too, when he came across an ad that it was for sale in Center Hall, Pennsylvania, in 2003. He made arrangements to meet the seller and check the car out, but their telephone conversation made the Mercury sound good enough that he knew he might need to come up with a way to get it home to Apalachin, New York.

“I had my brother-in-law go down with me,” Leonard recalled, “because if it was like (the seller) was saying, he could bring back my other car and follow me.”

And then it happened.

“I tried it out,” Leonard said, “and I had to have it. Put it that way.”

The Mercury’s condition was close to the way it had been described and he had no reservations about driving it several hours to Apalachin, but that changed fairly quickly and he had a conference with his brother-in-law.

“I wasn’t far coming back,” he said, “and I told him ‘I have a notion to take this back’ because they were working on the road, but it was grooved and the car had the bias-ply tires on it... It was awful. Years ago, you didn’t have any other choice. You never thought about it.”

He didn’t take it back, of course, and the trip home was uneventful other than the occasional need to fight with the grooved pavement. It’s not difficult to guess what he did after he got home.

“That was the first thing I did,” he said, “I took the tires and wheels off. A friend of mine ordered a set of radials for me… I took them down to the garage and they mounted them. It was like I had an entirely different car.”

While the necessity of swapping the tires could have made him start doubting the wisdom of his decision to buy the car, it was a minor problem that was far outweighed by the car’s overall condition.

“It was a complete frame-up when I got it,” Leonard said, “and it was painted like it is now. The front and rear bumpers were rechromed, but I took every other piece of chrome off of it and sent it up to a plater in Massachusetts and they restored it, other than the molding on the bottom. I was going to send that to see what they could do, but the guy who owns the body shop in Little Meadows (Pennsylvania) said ‘I’ve got a guy who can polish that.’

“He took it and polished it and it looked as good as any of the rest... Then I got all of the new clips for everything I took off. Everything I got new for it rather than try to use the old ones.”

In Good Shape, But Needing Some Work

Although the bodywork and paint had been completed by the previous owner, the Mercury needed help before it would look the way it does today. The taillight lenses were crazed, Leonard said, and had faded badly enough to require replacement.

“The emblem on the trunk lid is red now,” he continued. “That’s a new one. The one that was on there when I got it was closer to pink. And the one on the hood, that’s a new one and the little ones on the sides, on the fenders… My wife helped me out here. She has a little bit more patience. I’d have to walk away for a while and come back to it.”

Since he was replacing the taillights, he decided to replace their wiring harness at the same time. Next was the windshield, which had picked up a stone chip not long after he’d bought the car. The replacement came from a local glass shop and while the damage was small, he said it had to be addressed.

“Anything like that bothers me,” he said. “Anybody else probably didn’t see it and it was on the passenger side. It bothered me more than if I’d had dirt or a bug on my side. I had to get rid of that.”

Leonard had more patience when it came to the interior.

“The interior was original,” he explained, “and the (seller) was going to leave it that way. Well, the more I drove it, the more I saw that it needed to be redone. The seats, all of the padding every time I’d drive it was coming out onto the floor. It was shrinking. It was actually crumbling. I took them to an upholstery shop and had that guy re-do all the seats.

“I got all new material. He redid the door panels and even (the shelf) at the back window. He changed that because that had a piece of rug and they didn’t have that. I think it was camouflage. I got that redone, but to this day, the headliner and the sunvisors are original.”

Going Under the Hood

The engine, too, is apparently mostly original.

“I’ve got nothing saying that it was ever redone,” Leonard said, “but it won’t burn one drop of oil from one oil change to the next. It’ll never go down a bit. I think it had to have been re-ringed, but I don’t know. That guy never said anything on it.”

The odometer showed 65,000 miles when he bought it and it now shows 80,000, so it’s certainly possible that the V-8 has never needed any major work. Still, Leonard has had to give it some attention and said that when he reinstalled the carburetor after it was returned by the shop that had rebuilt it, he found it had problems.

“I couldn’t get it to idle,” he said. “I got on the phone and they said ‘you bring it up and we can take care of that while you have a cup of coffee.’ I said ‘I’ll be up Monday morning.’ I was there when they opened the doors and it was a good thing because I got there and one of the guys who had worked on it came out and there was an air leak. They had set it on the wrong gasket where it’s mounted. They ended up putting two gaskets on it. They probably didn’t have the right gasket. It’s been perfect ever since. Coming home, it was entirely different. You’d never know (there are two gaskets) because they’re so thin, but I’m almost positive that that’s what they did to cure that air leak.”

He also replaced both water pumps and when it developed a noise, the fuel pump.

“When I was in the service,” he said, “it happened on a ’46 Ford and I took it off to get another one or to try to fix it. When it went, I came to find out that the pushrod in it, just so much of it on the top is ball-like. It wore off “I’m glad I’d experienced that because this one had a noise and everyone was saying all this and that. I thought ‘I’m going to try one thing’ because I’m almost sure they always had a doubleaction fuel pump and I’d had a problem with that on the ’53 I’d had years ago. I’d put an electric fuel pump on that one, but for this one, I got it from MAC’s Antique Auto Parts and I said ‘send me the pushrod, too.’ I got it. I knew what I was going to be looking for and boy, (the original) was shorter.

“That one I had in the service, that ’46 Ford, back then you just fixed them anyway you could to make them run. I took electrical tape and made a ball that just fit up in the fuel pump, put it back together and it’s probably not around now, but it ran for the rest of my time with it.

“I’m almost sure the rod’s steel, but it’s got that little (top) like an eraser on a pencil. They wear out. That’s the second one; I learned on the first one.”

He doesn’t carry a spare, he said, because with the relatively short distances he drives the car, he doesn’t see the rod wearing enough to leave him stranded. As a Ford product with a flathead V-8, it’s likely that a failed fuel pump or nearly any mechanical problem the Mercury might experience is going to be one whose solution is known.

No less important, it’s hard to imagine a mechanical part that’s not available for the car and for someone who enjoys driving, that’s a key consideration.

A Photogenic Road Car

The feature car has covered only about 15,000 miles in the time he’s owned it, but Leonard said that it’s made trips of more than 100 miles and knows it’s ready to do so again at any time. When it makes one of those trips, he said, it draws attention even when he’s filling the tank.

“I get people every time,” he said. “They’ll be pumping gas or when they come back out after they pay or before they go in, they’ve got to come over and they start really checking it out. Then they ask ‘would be it be OK if we take pictures of it?’ My wife is sitting there and she says ‘go ahead, we don’t mind.’”

Some who see it go a step further.

“I was at a show in Pennsylvania,” Leonard recalled, “and a man and woman who had one when they got married wanted to be able to sit in it and have their picture taken in it.”

It’s no surprise that he said the Mercury’s only real surprise on the road would be the brakes. They don’t compare to modern discs, he said, but stop the car as they should if the driver has taken the time to develop a feel for them. And with manual steering, he said, parking can become a challenge.

“It’s a good thing it’s got a big steering wheel,” Leonard said. “You don’t want to sit and try to turn it because it’s not going to work. You’ve got to have it moving just a little bit.”

In other words, it drives as an early1950s car should drive. Leonard had driven enough Mercurys like it to decide very quickly—very quickly—back in 2003 that buying the car had been the right move. The bias-ply tires might have raised some doubts, but only briefly, and those doubts had vanished long before he got the Mercury home.

“Oh, the car was beautiful other than the way it steered or the way the road handled the tires,” he observed. “Other than that, it was just a good car, really. I know my cars pretty well and once I got the right tires, I thought I had gotten something.”