1949 Nash Ambassador Brougham

It Had Uncommon Styling & an Uncommon Interior and Engine. Let’s See, Just What Is “Average” About This Car?

BIG. THAT IS the overwhelming first impression you get when sliding behind the wheel of a 1949 Nash Ambassador Brougham. Because of its rounded aerodynamic shape the car may appear to be smaller than it actually is until you approach it. But then swinging open that wide door and slipping into the cushy over-stuffed front seat is easy…and it’s as comfortable as the La-Z-Boy in my family room.

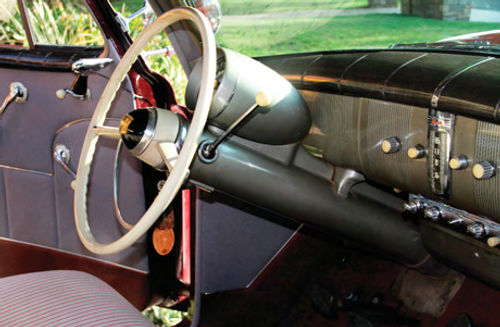

The dash is a long way in front of me under the windshield, but the speedometer and instrument cluster is housed in a bullet-shaped nacelle that Nash called a Uniscope, which is mounted on the steering column. The cluster is easy to read in an almost heads-up position, requiring only a slight downward glance from the road. (Sounds like a rather modern idea, doesn’t it?)

To start our test car—equipped with a standard transmission with Borg-Warner electric overdrive—I fully depress the clutch to engage the starter, and give it a little gas. If it had been equipped with the optional GM Hydra-Matic transmission I would have pulled up on the gearshift lever in neutral to engage the starter.

The overhead valve 234.5-cubic-inch inline six comes to life almost instantly and after a moment of subtle tappet noise, it settles into buttery silence. Acceleration is adequate but conservative when compared with the Oldsmobiles and Cadillacs of the day. The transmission shifts easily and smoothly with no clashing of gears. Top speed (89 mph) with overdrive is more than adequate for freeway driving.

About That Engine Design

The displacement of the Ambassador six may seem a bit diminutive now, but it was not small for the era. And like most inline sixes it produced plenty of low and mid-range torque, which was appropriate when you consider that the typical highway speed limit at the time was 50 miles per hour.

The engine’s seven main bearings made it very robust and smooth as well. However, there are a few things about this, as well as other Nash engines, that are unique.

For example, there is no separate intake manifold. Instead it is cast into the head as an integral unit.

Also, there is no exhaust manifold. There are just curved ports on the side of the head, and the exhaust pipe, which has holes in it at the appropriate locations, is clamped to the side of the head. It works fine, but it does seem that the exhaust pulses having to make such abrupt right angle turns would create a fair amount of backpressure. Another feature of the engine that seems a bit anachronistic is that a shaft off of the generator drives the water pump.

I have not driven one of Nash’s less expensive 600 models with the smaller, less powerful 172-cubic-inch flathead six, but I’d surmise that it would be somewhat leisurely off the mark. But then you can’t have everything. Those models were called the 600 because Nash claimed the car could travel 600 miles on a twenty gallon tank of fuel. For the numerically challenged that’s 30 miles per gallon! If it’s a viable number, that’s not bad for a big comfortable car—provided you aren’t in a hurry.

A Surprising U-Turn

We begin our drive by swinging the sleek Ambassador sedan out onto the main road and take it up through the gears at a moderate pace. Bumps are only implied thanks to soft coil springs at all four corners. There is very little body lean when cornering because of the big anti-sway bar up front, and the steering is light for such a large machine. The word “nimble” would notspring to your lips while driving a 1949 Ambassador, but what can you expect from a car the size of your living room? (It’s 210 inches long, 771 ⁄2 inches wide and sits on a 121- inch wheelbase.) On the plus side, it is well-balanced and predictable. Brakes are very good for the era.

I had always wondered if these aerodynamic Nashes with their skirted front fenders would require a big turning radius, but it’s not, in fact, appreciably bigger because the front wheels are five inches closer together than those in the back, and this allows the car to do a U-turn in close to the same turning circle as other cars of the time.

Besides, none of the cars of 1949 could turn very tightly with their king pin and bushing steering.It wasn’t until ball joints debuted in the mid-’50s that tight U-turns were possible.

But then American cars of the late-’40s and early ’50s were not designed for sporty driving, and none of them handle and ride like modern cars. They were intended more for taking the family on long trips on the new highways being built around the country at the time.

An Obvious Attention-Getter

People pull alongside and gawk as we drive the big Nash. Some give Bob Walker, the car’s owner, and I a smile and a thumbs-up. Others just want to see who the old guys in the old car may be. I should have dressed in a double breasted gabardine suit and bow tie, with a fedora square on my head ala Harry S. Truman. It would have completed the picture for some of the more mature spectators. At any rate, because of the car’s size and its unique shape it gets attention wherever it goes.

The so-called “bathtub” (I prefer “cucumber” if the car is green) Nashes were designed by Finnish-born engineer Nils Eric Wahlberg who came to work for Nash in 1917 from General Motors. By the ’40s he was into aerodynamics and had access to a wind tunnel, thanks to Nash’s wartime efforts.

The resulting design was called the Airflyte, and it had a very low drag coefficient for the day. Other manufacturers also had rotund envelope body styling in the late ’40s, such as the 1948-50 Packards, and the contemporary Hudsons, but neither of those manufacturers were into aerodynamics.

Nash’s hype about aerodynamics was more than just an advertising ploy. At highway speeds the Airflytes produced 20 percent less drag than other full-size cars of the day. An Airflyte, in fact, created 113 lbs. of pressure at highway speeds, while a contemporary Packard made 171 lbs. of drag, meaning the Packard was pushing around a lot more air, and as a result, it burned more fuel.

Unit Body Pioneer

Another innovation that was taking hold in the late ’40s was unit body construction. Both Nash and Hudson were into it and it turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. Unit body construction meant that—though the Nashes were substantial—they weighed less than their full-framed contemporaries at just 3325 lbs.(A much smaller contemporary Chevrolet weighed 3225 lbs.) The low weight made for better handling and performance. (For Hudson the weight savings and low center of gravity meant that it dominated the stock car circuits in the early ’50s.) But the technology also was a curse because it was more expensive to update the styling on such cars.

A Minister’s Car

Bob Walker and his wife Wendy of Anaheim, California, are serious Nash collectors, and Bob makes some of the hard-to-find parts people need for them. “I don’t do it for the money, but to help keep Nashes on the road,” he said. A lot of collectors have him to thank for the crucial driveline rubber parts that keep their Nashes mobile.

In addition to the 1949 Ambassador Super Shown here, a partial inventory of the Walkers’ collection includes a 1937 convertible coupe and a 1954 Nash Healey sports car They acquired the ’49 a few years ago from a retired ministers in Liberal, Kansas, who had owned it from new. Doctors had informed the reverend that he didn’t have long to live, so he decided to unload the Nash. Then he got well. And when he did he called the Walkers and offered them twice what they paid for the car to get it back. But by that time they loved the Nash as much as he did so they refused the offer. The minister then offered them triple what they had paid, but they refused that too. I can see why.

Other than a bare metal repaint, the car needed little restoration, and it is the rare two door-sedan with all of the sought after accessories including the exterior sun visor, locking gas cap controlled from inside the car, and Nash’s Weather Eye thermostatic heater. Although it didn’t include air conditioning, you could set the heater temperature you wanted in the car and the system would maintain it. Coupled with Nash’s flow-through ventilation system, the Nash owner was provided fresh filtered air all the time, making for more comfortable touring.

This Ambassador also has a rear window windshield wiper, foot-pedal operated radio with two speakers, and seats that fold down into a comfy bed at night. (I could have used this feature in my misspent youth after imbibing a bit too much at parties.) There is plenty of room for two to sleep in comfort, and the brougham back seats with a “card table center console” are as luxurious as the first-class parlor car on a train of the era.

Another extra-cost accessory with an interesting evolution is the hood ornament on the Walkers’ Ambassador. It was designed by George Petty (1894-1976) of Petty Girl pin-up fame, whose work was featured in Esquire magazine. He was commissioned By Nash-Kelvinator to design the deluxe accessory, and it is definitely one of the most elegant hood ornaments of the era, and worth every penny of its $9 original cost. I’m just surprised that the minister who bought the car new would have countenanced such a sensuous decoration on the hood of his automobile.

Try a Nash…You Might Be Pleasantly Surprised

By 1949 Nash Motors had been around for over 30 years and had done well even in hard times. The company was founded in 1916 when Charles W. Nash, who had been president of General Motors, bought the Thomas B. Jeffery Co.,maker of Rambler automobiles. Rambler was a name the company would drop, then revive in later years.

Charles Nash also managed to talk Nils Eric Wahlberg, chief engineer for GM’s Oakland car division, to work for him. They produced the first automobile bearing the Nash nameplate in 1917. It was a success, but then the U.S. entered World War I, and the company produced four wheel-drive Jeffery trucks for the Army.

After the war Nash continued to do well in the early ’20s, building mostly mid-priced cars with value for the dollar. The company’s motto was “Give the customer more than he paid for.”

Then as the roaring ’20s roared on and the country became more prosperous, Nash began producing more upscale cars with overhead valve inline sixes and eights and very handsome styling.

In an effort to expand market share in 1925, Nash also came out with a low priced offering called the Ajax, which was built in the recently acquired Mitchell Motor Car plant in Racine, Wisconsin, as well as the La Fayette plantin Milwaukee, that Nash Motors also acquired around that time. The Ajax did not meet sales expectations, so the company renamed it the Nash Light Six to trade on the Nash name and reputation. This worked out so well that Nash offered a kit to convert existing Ajax cars to the Nash Light Six badging.

The LaFayette name was reintroduced in 1934 and became the company’s low priced offering,replacing the Light Six.

The 1930s were good for Nash, and the company became rather innovative at a time when other independents were just trying to survive. During the ’30s Nash introduced the aforementioned Bed-In-A-Car in which the seats folded into a comfortable bed, and it also came out with its conditioned air system that pulled in fresh outside air through its heater, filtering it as it did so. Later a thermostat was added to the system that allowed it to maintain the car’s interior at a constant heat setting.

This revolutionary ventilation system was partly the result of a 1937 merger of Nash with Kelvinator, a major producer of refrigerators and other kitchen appliances. At that time Charles Nash retired and turned the reins of the new company over to Kelvinator head George Mason. It was a unique partnership of dissimilar companies, but it worked out well for both.

The new Nash 600 series replaced the LaFayette in 1941 and it was the first mass-produced car in the U.S. with unibody construction. Granted, the Cords of the mid-’30s were unit bodied, as were the Hupmobile Skylarks and the Graham Hollywoods, but very few of those were actually built.

After World War II, Nash and most other manufacturers offered essentially warmed over pre-war models through 1948. But then Nash set the automotive industry on its ear in 1949 with its new Airflyte aerodynamic look. This new direction in design was such a startling departure from previous models that it took some of the buying public a while to grow accustomed to it. But if they had taken one of the new Ambassadors out for a spin, they no doubt would have been drawn in with its size, comfort and innovative design.

I know I was. The Ambassador is a distinctive car that would be perfect for long distance touring. And you wouldn’t even need a motel at the end of the day. You could just pull into a rest stop; make the bed and go to sleep.