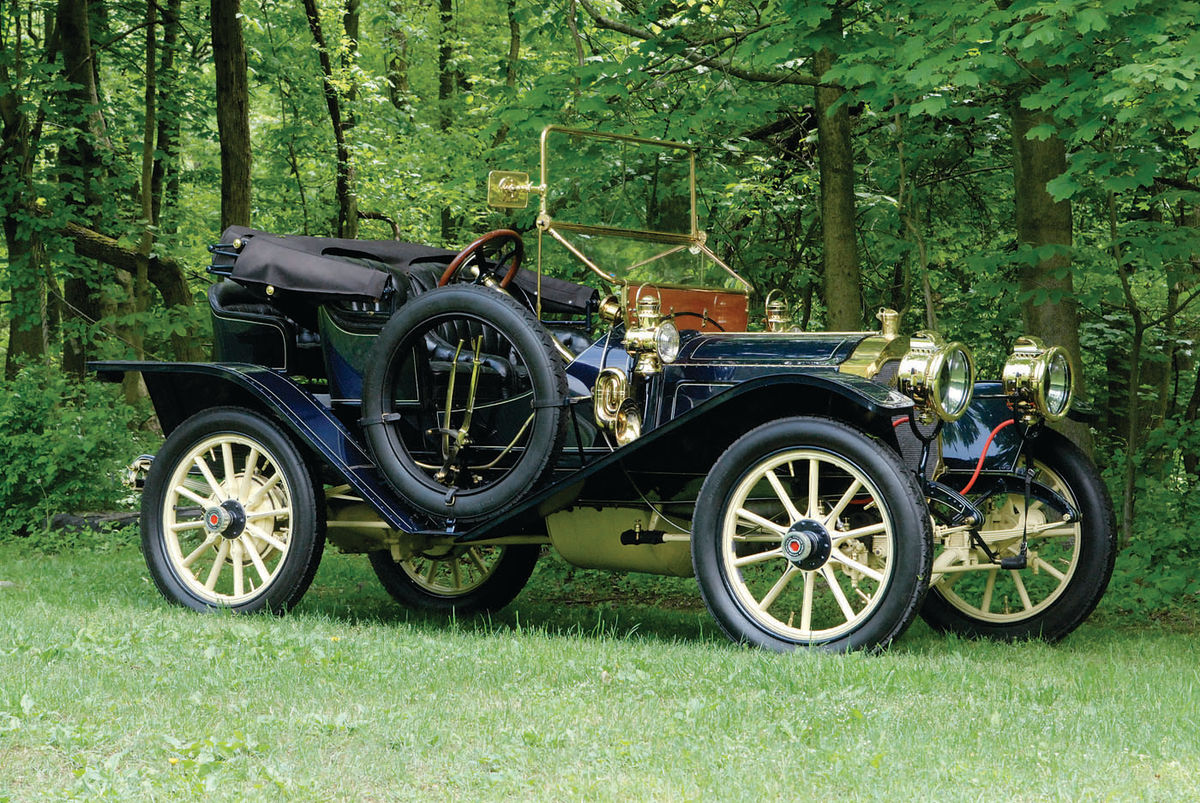

1910 PACKARD MODEL 18

For Years He Was In the Market for Something Old…Really Old. Yet He Intends to Drive This Car and Not Just Display It.

A SPOON IN A tree, a Model T behind a gas station and a long-held dream all tie into Wayne and Kim Simonis’ 1910 Packard Model 18 gentleman’s roadster. So do a book on Packards and an encounter with several buzzards.

“I’ve always liked old stuff,” Wayne Simoni said. “I was always fascinated. As a kid, we had a cabin up in the redwoods and I remember finding something in an old redwood tree, a spoon, and looking at it and saying ‘I wonder who was here 100 years ago. The settlers or something and they used this spoon.’ It was just an old thing.”

Maybe it really was nothing more than “just an old thing,” but the fact that the spoon caught his attention was a hint at what was ahead.

“When I got into the hobby almost exactly 50 years ago when I was 16,” Simoni said, “I saw a 1923 Ford in back of a gas station. I thought it was the oldest car on the planet. I was sure it was. Then I started seeing older cars. I bought that car, by the way, but I started looking around and I just fell in love with the Packards. I thought they were just gorgeous and then I heard that they were high-quality cars and by the time I got into my twenties, it was ‘I wish I could afford a Packard.’”

An Auto Company Started by a Rebuff

A lot of people have made the same wish in the years since the first Packard was built late in 1899. More prototype than production vehicle, the Model A was a simple runabout riding on a 71.5-inch wheelbase and powered by a nine-horsepower single. That description is almost deceiving as it’s similar to what could be said of hundreds of early cars, so a brief look at where the Model A came from is a much more important piece of Packard’s history. The company that went on to build some of the most widely esteemed high-quality American cars got its start almost accidentally, not long after James Ward Packard bought an 1898 Winton. Packard was not entirely pleased with the car and visited the Winton Motor Carriage Co. in Cleveland to discuss his concerns. Founder Alexander Winton was less than receptive to suggestions and in effect told Packard that if he didn’t like the Winton, he should go home and build his own car.

Packard accepted that as a good idea and returned to Warren, Ohio, where he and his brother, William Doud Packard, manufactured electrical components. By 1900, their Ohio Automobile Co. was building Packards and had advanced far enough that it was able to display cars at the New York Auto Show. That year’s Model B, like its predecessor, was a single-cylinder, nine-horsepower runabout with a tiller for steering and a two-speed transmission. But the 1901 Model C brought change. The transmission optionally became a three-speed, several body styles were available and the Packard now had a steering wheel instead of a tiller. In addition, increases in both bore and stroke boosted the one-cylinder engine’s displacement from 143 to 184 cubic inches and its horsepower from nine to 12.

Packard accelerated its evolution in 1902 with the launching of the Models F and G. The G introduced a 24-horsepower two-cylinder, but the F was actually the more significant car.

Continuing with the Model C’s engine, the Model F used a wheelbase eight inches longer and with the G went from a planetary transmission to a sliding-gear unit as standard equipment. But perhaps more importantly, the overall design showed thinking that was moving away from vehicles that looked like a horseless carriage.

A New York dealer boasted that “our foresight was good! Early last fall, few factories had their 1902 models designed or tested, but the 1901 model Packard was so satisfactory, and we had so much confidence in the ability of the Ohio Automobile Co. to produce the best American Gasoline Car, that we placed a large order for early delivery. A good many of them are now in the hands of satisfied customers. A few are ready for immediate delivery. They will not last long after the many Packard enthusiasts learn of it. No machine in this or any other country is more graceful or powerful. It is a machine that satisfies the most critical.”

It also was a machine whose success brought changes at the corporate level in 1902 as the Ohio Automobile Co. became the Packard Motor Car Co.

By 1903 the operation was preparing to head for Detroit as it also was introducing the Model K. The K broke further ground for Packard by carrying its first four-cylinder engine. It also cost the equivalent of more than $180,000 in today’s dollars and that leaves little doubt about the market the company was seeking.

Two years later its engines changed from flatheads to T-heads and by 1907, horsepower had reached an even 30. Prices kept the Packard in the upscale market and the Model U — or Model 30 — topped the equivalent of $140,000 in 2013 dollars and that almost certainly explains the company’s decision two years later to introduce the Model 18.

With wheelbases of 102 and 112 inches depending on the body style and an 18-horsepower, 266-cubic-inch four, the Model 18 might have been expected to sell at least as well as the Model 30. After all, the Model 30’s wheelbases ran from 108 to 123.5 inches and not everyone wanted a car that large. Price, too, was a factor in differentiating the pair and a frugal but wealthy purchaser could save as much as $1200 on a limousine by opting for the Model 18 instead of the Model 30. If $1200 doesn’t seem like much, consider that its equivalent today would be about $31,000.

At First, He Didn’t Succeed

It’s at least slightly surprising, then, that the Model 18 didn’t sell as well as the Model 30. First-year deliveries reached only 802 against 1501 Model 30s. The 1910 figures were even less encouraging at 766 vs. 2493.

But for the feature car’s owners, appearance mattered far more than comparative sales numbers. Simoni said that the Packard appealed so strongly to him that long before he owned it, he used an illustration of it in advertising for his business, Classic Auto Part Reproduction Services. Although not specifically the Model 18, the appeal goes back further.

“When I met Kim 30 years ago,” Simoni said, “I was talking about how someday, I wanted to own a Packard. She bought me a Packard book. I’ve owned a Packard book for 30 years, but I never had a Packard.”

Although he lived in California at the time, he first encountered his Model 18 at an event in either New York or Pennsylvania about 15 years ago. It was owned by Walt and Jane Grove in Pennsylvania and Simoni recalled one of the times when he saw the car.

“I asked Walt if I could take a picture of it with my wife standing next to it,” he explained, “and Walt said, ‘oh, she can sit in it.’ She sat behind the wheel and I have that picture today, a beautiful picture of her sitting in that car.

1910 Packard Model 18

GENERAL

Front-engine, rear-drive roadster

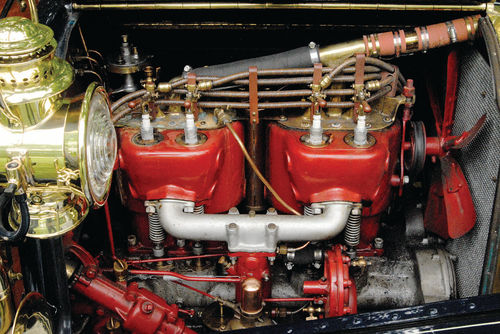

ENGINE

Type T-head in-line four-cylinder

Displacement 267.5 cu. in.

Bore x stroke 4.0625 in. x 5.125 in.

Carburetor Single-barrel updraft

Power 18 hp @ 650 rpm

DRIVETRAIN

Transmission Three-speed sliding gear

SUSPENSION & BRAKES

Front Solid axles, leaf springs

Rear Solid axles, leaf springs

Brakes (f/r) Mechanical, on rear

MEASUREMENTS

Wheelbase 102 in.

Tire size 34 x 4

“Living 3000 miles away, I didn’t realize that Walt had later died and the car had gone away; otherwise, I would’ve tried to find some way to buy it.”

Then He Bought It and Went on Tour

By May of this year, however, he’d found that way and after passing through another owner’s hands after the Groves had owned it, the Packard belonged to the Simonis. The day after it was delivered, they drove it more than 100 miles on the Brass in Berks County (Pennsylvania) tour.

“I saw that Jay Leno has a Model 18 touring that he made into a gentleman’s roadster,” Simoni said at the end of a day of touring, “and on his video on YouTube he says ‘this car shifts so sweet.’ I was expecting that and it does. It shifts really sweet once you get the hang of it. It just drops into gear and it’s wonderful as opposed to the ones where you’ve got to synch it, double-clutch it, get it just right. It pulls about as well as I thought it would. I’d heard they pull pretty well and it does.

“The brakes were way out of adjustment and so that scared the heck out of me at first. It has some adjustment and I adjusted them. But the steering is quick and without power steering, having quick steering is weird because you’ve got to really, really turn it. And the tires are large-diameter, so it steers really hard. I think somebody who’s 85 is not going to be able to drive that car.”

He also confessed to having been worried about every noise the Packard made, a reasonable approach even though the car has been touring for decades.

Hearing From a Previous Owner

Jane Grove recalled how she and her late husband acquired the car, beginning with the fact that she started setting aside the necessary money after seeing a 1909 Packard at Hershey in 1958. The funds never quite caught up to the prices, she said, and were often tapped to meet needs that were considerably more pressing than a Packard. By the mid-1980s they owned other cars and again started saving for a Packard. A 1910 touring that needed restoration was for sale, so they sold their 1903 Ford and bought it.

“So now that one was sitting at home,” she said, “needing to be restored and Walter started working on it. A few years later, I saw another ad for a Packard roadster. We called about that and the seller was not home. But when he got home from vacation we were the second people he called and we were on the road the next day with the trailer.”

They were already experienced at touring, so the Model 18 was placed in service and that was where the buzzards came into the picture. It happened during a one-day tour in southeastern Pennsylvania when a tire went flat and the spare, unfortunately, proved to be the wrong size. Another car on the tour finally came by and Grove said its driver gave her husband a ride.

“They went back for the trailer,” she said “and (a friend) and I stayed there with the car. We stayed there and we stayed there. After about half an hour, there were five turkey buzzards that started circling us. Now if this isn’t disconcerting, I don’t know what is.”

Back to Basics…For the Most Part

The Simonis’ first day on the road with the Packard was less dramatic. Beyond the brakes, the car needed only minor checking and adjustments. Barring some problem that’s yet to reveal itself, it won’t receive much more, although changes made somewhere along the way will be undone.

“I don’t think I have to do too much to keep it alive,” Simoni said. “There’s just going to be a couple of cosmetic things and I’m going to bring it back to a 1910 Packard. People try to ‘improve’ things. Every car I’ve ever bought has been improved and usually it’s like a bolt-on carburetor. I can’t think of a case where it’s actually improved it because when I’ve gone and researched it and bought the correct carburetor, put it on and adjusted it correctly, it’d run every bit as well as it did with the ’50s carburetor, every time, every car I’ve ever had.

“This car I’ll bring back exactly as it came from the factory with one exception. It has halogen headlights, bulbs. I’m going to bring it back so that the acetylene gas works, but behind that will be the halogen bulb. I’m going to make a mechanism where the bulb’s down, you can light the gas and everything’s fine, and in an emergency, you fold it up, hit the switch and you’ve got headlights. The taillights are going to go away. Blinkers? (A hand signal) still works, so they’re going to go away.”

Maintenance, he said, will be mostly a matter of proper lubrication, the extent of which might surprise someone whose experience is limited to more recent cars.

“You need to lubricate lots of things,” Simoni said, “all the linkages and stuff that modern cars don’t have. It’s got a transaxle, which is a transmission and a differential in one and the oil is apparently separate. There are two quarts in each one. I want to check the front wheel bearings because on the old cars, you have to pack those bearings. There are some other lube things like maybe the distributor part of the magneto that gets a couple of drops of oil. With all of these things, you just make sure they’re lubricated. That’s pretty much all of the maintenance.”

But then, there are those adjustments.

“The valves,” Simoni said, “definitely when I get home from (our current tour), will be one of the things I’ll check to make sure they’re adjusted correctly. Who knows how far this is out? Is it noisy because it’s supposed to sound like that? Is there a noise that’s supposed to be there that I don’t know about? Should it be quieter? I don’t know, so I’m going to look at that stuff.”

This attention to mechanical detail does point to one of the facts of life when it comes to brass cars. To varying degrees, most of them occasionally will need an owner’s involvement ranging from tinkering to adjusting.

So for a first-time buyer, something like the Simonis’ Packard might not be the best choice because of its rarity. A Model T Ford would be a smarter buy if for no other reason than the fact that its great popularity means there’s probably not one problem that hasn’t already been solved by some other owner and not one fact that isn’t known. For the driver of a Model T, it’s hard to imagine any situation where help isn’t readily available. The supply of parts, too, argues strongly for the Model T.

Packing Can Be a Challenge

But while finding parts — and expertise — for the Packard would be more challenging, it does have some common ground with the Model T. There is, for example, the question of how to deal with luggage and basic tools when touring.

“Last year,” Simoni said, “we did a circle tour for the first and only time and we borrowed a (Model T) torpedo roadster. There’s a trunk on the back and no seat, so we put one of those expanding running board attachments on it and put one suitcase in there, a soft bag. We brought enough basics for 10 days or whatever the tour was and we had the other bag strapped on the trunk on the back. We strapped them on with bungees and we went down the road.”

The Packard’s larger size would be of some help thanks to the greater surface area it provides.

“I would take it,” Simoni said, “because there’s the (mother-in-law) seat and we could bungee a large soft bag onto it, but then in front of the seat, between the back of the roadster seats and that mother-in-law seat, there’s kind of a big space. You could put a lot of soft stuff in there, so for two people, it’d be fine.”

The idea of a tour requiring that kind of packing can be startling to those who aren’t experienced with brass cars, but Simoni emphasized that the Packard won’t be made so perfect that he’d hesitate to drive it.

“This is a beautiful, nice-running car,” he explained. “It’s never going to be restored in my lifetime. It’s always going to look nice, everything on it’s going to be fixed, it’s going to work well, but it’s not going to sit in a museum. It’s going down the road.

“I like old cars. Like I said, when I was 16, I ran into an old car. I’ve always liked them. I bought that ’23 Ford and when I learned there was something older than a ’23, I was like ‘I want an older one. How old can I get?’

“I finally had a demarcation point. I like them when they have driveshafts and I didn’t want to go too far back like to chain drives like some of the old Cadillacs. I appreciate them, I love them, but personally, I just want a little bit of an upgrade to where it actually has a driveshaft and four cylinders. That was kind of my break-off place. That’s why 1910-kind of cars hit the mark for me.”

If the “1910-kind of cars hit the mark” for him, then the Packard hits it with surgical precision.

“I’ve always loved that style,” Simoni said. “I thought it was just a gorgeous-looking car. It’s about 10 inches shorter than the Model 30. I don’t like the really, really big cars, but I like the quality and the aesthetics of that car so much that I wanted that particular car or if not, one of the other three exactly like it.”

Sometimes, a plan really does fall into place and maybe in more ways than are immediately apparent.

“I know the right people have it,” Jane Grove said.

“They wanted it for so long.”