1965 Plymouth Barracuda

He Bought This Car New and Has Owned It For 50 Years. And At Times He Still Has to Step Hard On the Accelerator.

A FTER A HALF-CENTURY, Bob Williamson knows the 1965 Barracuda Formula S that might have seemed like an impulse buy at the time actually was the right move.

“My wife and I with one child lived on the ground floor of a three-floor apartment building in Northampton, Pennsylvania, at the time,” he recalled.

“Denny and his wife and their baby lived on the third floor. Denny was the mechanic at Eberhardt Chrysler-Plymouth in Egypt, which borders Northampton.

“I had a ’58 Plymouth Fury which Denny really liked because he was a real Chrysler fanatic, and he knew I was looking for a new car. He showed me pictures of the Barracudas and I liked them. I didn’t really want a Mustang because everybody had them and Chevelles were so-so. The Malibu was a nice car, but it was just a nice family car.

“So he said ‘you’ve got to come up to the garage and see this Barracuda that we just got in.’ My wife and I looked at it in the garage, I loved the looks of it and when they started it up, the sound that it made? I was in my mid-20s at the time and I thought ‘this is what I want to hear.’ We bought the car immediately; I didn’t take it off of the lot at that time, but I made the arrangements to take it.”

There also was something else he didn’t do before making the purchase.

“Didn’t have to drive it,” he said. “I just heard it and it looked good enough to me.”

Plymouth Comes Up to Speed

Then, as now, whether a car looked good enough was a matter of taste, but even those who weren’t fans had to concede that the Barracuda stood out. Considering the Barracuda’s family tree, it was an impressive achievement for Plymouth, but not a completely surprising one.

The post-war years were a particularly trying time for Plymouth as its entry-level position in the Chrysler hierarchy gave it not only the lowest price, but with a 111-inch wheelbase on the Deluxe and just 97 horsepower from a 217.8-cubic-inch six, the shortest length and the smallest engine.

That slot had been a good one for Plymouth from the beginning and had enabled it to thrive, but the world was changing and at least for a while, Plymouth was about to be left behind.

The problems for Plymouth (and everyone else) began when Cadillac and Oldsmobile introduced modern oversquare V-8s for 1949. Chrysler introduced the first of its Hemi V-8s in 1951. Matching Cadillac’s 331 cubic inches, its 180 horsepower was ahead by 20 and although its design was more complicated than those of either GM V-8, it had great performance potential. Appearing first in the New Yorker, the Imperial and the slightly smaller Saratoga where it replaced the previous year’s flathead eights, the Hemi next saw its variations in the 1952 DeSoto and 1953 Dodge.

Plymouth, meanwhile, trudged on with only its flathead sixes and while still an excellent value, a problem was becoming clear. Production climbed from 474,836 in 1952 to 662,510 when 1953 brought a completely new modern body and a semi-automatic transmission. But the numbers fell to 399,785 for the lightly restyled 1954 model even though a fully automatic transmission was now available. The division’s official history, “Plymouth. Its First Fifty Years,” attributes the drop to the difference between the cars the public claimed that it wanted and the cars it actually bought. In effect, Plymouths had become too practical, so a big change was called for and it came in 1955.

Buyers now saw cleaner, straighter lines, a wraparound windshield and backlight, hooded headlights and high-mounted vertical taillights. It was the Forward Look, a theme shared among the entire Chrysler family, but it was only half of the surprise at Plymouth since the low-price division now had its own V-8. At 241 cubic inches and 157 horsepower, the new engine offered a 40-horsepower boost over the still-available flathead six and that was in basic form. The 260-cubic-inch version was good for 167 horsepower or 177 when equipped with a PowerPack option. They weren’t Hemis, but Plymouth made its point with production turning around and hitting 743,001 for the year.

Taking More Steps to Raise the Plymouth Profile

Riding that kind of success and obsessed with the creation of a completely new reputation, Plymouth followed in 1956 with the Fury, a high-performance twodoor hardtop sporting gold trim and a 240-horsepower 303.

The Fury took a turn in 1959 and became simply the top Plymouth, meaning that a buyer now had to order the individual components to come up with something comparable to the original.

Concurrently, during the 1950s Detroit had gradually recognized the challenge presented by foreign cars finding their way to the United States. Led by Volkswagen, the compacts had been making inroads and were now about to be met with homegrown competitors including Chrysler’s 1960 Valiant. Weighing in at less than 3000 pounds and riding a 106.5-inch wheelbase, its 170-cubic-inch engine—the new overhead-valve Slant Six—generated 101 horsepower, but for those who didn’t really see that as sufficient, there was the Hyperpack option. Substituting a fourbarrel carburetor for the single, raising compression from 8.5:1 to 10.5:1 and adding other improvements bumped horsepower from 101 to 148.

A 225-cubic-inch Slant Six with the same 148 horsepower was the option for 1961 in what was now the Plymouth Valiant and while neither engine was as outrageous as those that would follow, they predicted a future in which the decades-old formula of a big engine in a small body would finally take off. After all, compacts were everywhere and mid-size or senior compacts were appearing. The Valiant, while barely changed in length, seemed larger after a 1963 restyle that simplified its lines and added a convertible, but 1964 brought both a four-speed transmission and an optional 180-horsepower 273 V-8.

It also brought something bordering on radical, the Barracuda.

First You Take a Valiant…Cut Away a Section…And Then…

Every automaker in the world has at some point changed a feature or two and called the result a new car. Most such efforts don’t fool anybody and it’s not likely that the manufacturers expect them to do so, but sometimes the change really can result in a different car, which is what Plymouth accomplished by slicing the greenhouse and trunk from a Valiant and substituting a fastback made mostly from glass.

The roofline was smoothed and the trunk lid was reconfigured to provide a perfect sweep while a back-slanted rear post separated the side windows from a backlight that gave new meaning to “wraparound.” There were other, lesser distinctions in trim and sheet metal, but today, that Valiant platform provides pluses for anyone restoring a Barracuda. Like many of its competitors, the Barracuda’s chassis and drivetrain share most of their components with corporate relatives, making it unlikely that any critical part is going to be impossible to find. A Valiant parts car can supply much—not all, but much—of what the project might need, such as some body panels, interior pieces and trim. Overall, however, the changes that created the Barracuda worked well enough that it didn’t look like a Valiant variant despite its formal position in the Valiant line.

Some Very Unfortunate Timing

If success is a matter of timing, though, it was here that the Barracuda missed. The new car was introduced on April 1, 1964 as a 1964½ model and the Mustang arrived on April 17. Both were in a mostly unexplored market but the Mustang hit that target far better and far more quickly than did the Barracuda, which was overlooked in the wild frenzy surrounding its competitor from Ford despite their similarities. Both were based on existing models—even if the Mustang hid its Falcon underpinnings very well—and neither was conceived as an all-out muscle car. No one was using that term in 1964 and full-size performance models were still the norm, so the Barracuda and the Mustang were at first more sporty than all-out fast.

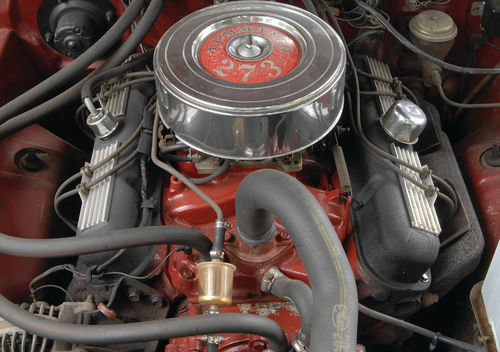

In the Barracuda’s case, the Slant Six was the base engine and the option was the 273 as in the rest of the Valiant line. But 1965 brought more choices. By ordering a Formula S, the buyer received a Barracuda including Rallye suspension, better tires and the 235-horsepower version of the 273.

“You got a 273,” Williamson said, “which is not a lot of cubes, but they put domed pistons in it, solid lifters, different cam, dual-point ignition, four-barrel Carter AFB, 10.5:1 compression and I’m probably forgetting some other things, but I’ll tell you what... It just runs like there’s no tomorrow.”

His car was delivered with a four-speed and Hurst shifter as well as a 3.23 SureGrip rear, he said, and before it reached 50,000 miles, the rear developed problems.

“It was making some good clunking noises,” he recalled. “They put new spider gears in it under the warranty and the mechanic was my neighbor. He told me at the time that the ring gear or the pinion, I forget which, was scored a little bit. He said ‘you won’t have any real problems. You’ll have a little bit of a whiny noise in there,’ which I never really noticed. It lasted another several years until it actually went out altogether.

“So I called Denny, my neighbor, and he brought up a 2.91 rear out of an automatic and we swapped them.”

It Definitely Performed On Request

After replacing the factory clutch several times, he made a swap there, too, and installed a Borg & Beck, which he said eliminated slipping under all but the most serious pounding. He knows about these things because the Barracuda has, on occasion, been pushed. He spoke of an evening encounter at a traffic light in Allentown, Pennsylvania, not long after he’d bought the car and another in Harrisburg, both of which ended in his favor, but the Barracuda’s first decade was spent primarily in providing everyday transportation. There were, for example, the shopping trips, although one of them stands out in Williamson’s memory even though it was his wife, Carol, who was doing the driving.

“I was sitting on the porch,” he said, “waiting for her to come back from the grocery store. She drives in the driveway, gets out of the car with some groceries and she’s got a big grin on her face. I said ‘what are you smiling about?’ She said ‘I just dusted a Camaro.’

“She said that when she drove it for groceries, the boys would want to bring the groceries out to the car just so they could see it and hear it.”

Time and an Accident Took Their Toll

“The rear quarters rusted out around the wheelwells really badly,” Williamson explained. “We had spent a vacation, a week or 10 days in South Carolina. I didn’t realize it, but the sand blows into everything. Well, the sand got into the trunk of the car from both sides down in the cavities and I probably had five or six inches of sand down in there for six to eight months. It ate the insides of the quarter panels just as well. You could see right through to the ground.”

When it comes to Barracudas, rust is a formidable enemy, but the feature car suffered some minor accident damage when it was lightly hit in the front. The accident happened in 1976 when the Barracuda showed more than 100,000 miles and on paper was worth very little.

“The insurance company called me,” Williamson recounted, “and said the value of the car at that time I think was something like $300. I said ‘alright, I don’t want to get rid of the car,’ which I didn’t. “‘We’ll send you a check for $300 and you can keep the car and the title,’ he said. ‘Just sign off that you’re taken care of,’ which is what I did.”

He then took it to a local body shop.

“I said ‘when you find a fender, put it on for me,’” Williamson recalled. “In the meantime, I bought my dad’s company car, a ’72 Oldsmobile. He got that for me for $400 and this was in ’76, so it was only four years old. A good car, an 88, so I changed the plates, I changed the insurance and I’m driving the Oldsmobile to work. About a month or two later, the fellow comes back with the Barracuda. He’d found two fenders and he put them both on, so I’m thinking ‘now, what do I want to do? Do I want to change the insurance and change the plates again? No, I’m just going to park it.’”

That took care of the accident damage and more.

“They were noted,” Williamson said, “for rust on tops of the fenders—both sides—maybe the bottoms of the fenders somewhat, but mostly the tops, and back around the back wheelwells where they would just rot away.”

The car with its rust-free fenders, though, was set aside for several years while he drove the Oldsmobile. During that time, however, the Barracuda’s lugnuts were stolen.

“That made a real problem,” he said, “because they’re through-the-hubcap. They’re about 2½ inches long, chromed— the chrome was peeling on them—and they’re 5/8-inch studs on a Formula S instead of ½-inch. It’s bad enough to try to find that type of lugnut for the ½-inch, but for the 5/8? You can’t find them.”

You can, however, find a machinist

“The cigar factory my dad ran had its own machine shop,” Williamson said, “and a good friend of his made me a full set, left- and right-hand thread, out of stainless steel. That’s what’s on the car now. The only thing you’ve got to remember—you wouldn’t want to learn it the hard way—is that if you mix stainless with other steel, someday it’ll weld itself to it, so every time I take them off, I load it up with (anti-seize compound) before I put them back on. But it looks great with the stainless on there.”

He said that the Barracuda was parked outside at first—which explains how the lugnuts could be stolen—and then moved into his father’s garage, not far from Williamson’s Trucksville, Pennsylvania, home. The new fenders were on it, but the other bodywork had not yet been done, so it came out of storage long enough for major repairs to the quarters and the rest of the body.

Are You Going to Sell It or Drive It?

“When I got the bodywork done,” Williamson said, “the first thing I did was take it across the street and fill the gas tank up. But as soon as I put gas in, I’m standing behind the car and I see the gas just pouring out about as fast as it was going in. Since then, the gas tank’s been changed, but it was all pinholed in the top half. It’s got a new tank, which was epoxied inside.

“Then it was put in the garage.”

Plans to rebuild the engine were reconsidered when the biggest problem was found to be slightly low compression in one cylinder and so the car remained parked, but it wasn’t exactly forgotten. There were plenty of offers from those who wanted to buy it.

“Most of them knew me, knew the car,” Williamson said. “But if my dad’s garage door happened to be up so you could see the back end of a Barracuda sitting in there, it drew the mailman and all kinds of people.”

His wife, he recalled, wanted to see him driving it again.

“I kept telling her ‘I’m going to get it back on the road,’” he said. “‘One of these days, I’m going to get it back on the road.’ My girls were grown up. I had a grandson, but probably after about 30 or 35 years, it registered in my mind ‘hey, wait a minute. I’ve had it this long. Why would I want to get rid of it now? There’s nothing really wrong with the car.’ What changed my mind was that I didn’t need another car for everyday driving, but I thought ‘wait a minute. I can put “classic” plates or “antique” plates on there and drive it a little bit.’”

To drive it even a little bit meant that it needed more than just fresh gas and a new battery, but the news there was good.

“It was very easy to get running,” Williamson said. “First of all, I took a breaker bar and made sure it wasn’t seized. Chris’ Auto in Dallas (Pennsylvania) does some of the maintenance work on it for me and he said ‘before you actually get it started, take the plugs out, fill the cylinders with Marvel Mystery Oil and just let it drain down into the crankcase,’ which we did. Then I had Chris come over and tow it out of the garage—we didn’t even try to start it—take it over to his garage, change the oil and the only thing he had to do to get that running was clean up the points. He didn’t change them. He just had to clean them off from sitting. He cleaned them up and the car started without much effort at all.”

It’s Still a Go-Getter and an Eye-Catcher

From that point on, he said, the Barracuda was drivable and has remained so with only minor work. And since it’s still the same car it was when it dusted that Camaro during the shopping trip, it’s capable of similar performance today, something Williamson demonstrated at an ice cream stop after a car show earlier this year. Limited sight-distance and heavy traffic, he explained, usually rule out a left turn out of the parking lot necessary to head for home, but not this time.

“I was going to go to the right,” he said, “and as I got out there, I saw that there was nobody coming in either direction. I started out onto the highway and I got right to the middle of the highway and Carol said ‘get on it.’ I floored it in first gear and between there and the overpass, which is only a few hundred yards, I had it tached out in first, I was into second and it was making a nice sound going under the overpass. People were looking from the ice cream stand and Carol said ‘that’s more like it.’

“I let off it. It’s fun.”

He said that five decades after he bought it, some of what attracted him to the Barracuda then catches the eyes of those who see it now.

“They weren’t that popular even when they were popular,” Williamson observed. “Everybody wanted the Mustang and everybody wanted the Chevelle, and I am just very glad I didn’t buy either one of them and I bought this. With this, I love it because everywhere I go, somebody’ll say ‘boy, I haven’t seen one of them in a long time.’”