1951 Chevrolet Styleline Deluxe Woodie Wagon

Is It Really a Woodie If It Doesn’t Have Wood on Its Exterior? Well, In This Case It Looks Like the Real Thing and It’s Easier to Keep This Car on the Road.

A 1951 Chevrolet Styleline Deluxe eight-passenger station wagon’s doors are big, so climbing in is easy. The bench seats are covered in leatherette, a leather-like plasticcoated fabric designed to be tough and long-lasting. The interior is roomy and handsome, although somewhat curious in that—though rich, real wood moldings with the feel of a classic ChrisCraft motorboat surround you—when you look out over the dash and hood you see a typical 1951 Chevrolet.

Off At a Leisurely Pace

I turn the key, push the starter button, and the inline six-cylinder 216-cubic-inch 92-horsepower engine gives a couple of lazy six-volt turns and comes to life. After a few seconds of warm-up with just the faintest ticking of tappets, it settles into a smooth, quiet idle. I pull the column-mounted standard shift lever into low and we are off for a spin through a local park. The engine pulls smoothly, with plenty of bottom-end torque, but it runs out of revs fairly quickly. Shifting is almost effortless with the short throws of the columnmounted lever. And except for the slight hum of the differential typical of station wagons, the car is quiet and comfortable.

If you were looking for speed and nimble handling, a 1951 Chevrolet station wagon would not be a good choice. But if you want smooth, comfortable, reliable transportation that would accommodate the whole family plus four bags of mulch, a couple bags of chicken feed and groceries for a week, this car was made for you. People called it a station wagon, but that is a misnomer. Let me explain:

That term comes from the days when hotels had what were called depot hacks, or station wagons, which were literally horse-drawn wagons with special enclosed wooden bodies intended for picking up guests at the train station. These were eventually replaced before World War I by automobiles with similar bodies and sometimes

lengthened chassis to accommodate more patrons. And then Henry Ford, who had a couple such rigs built for driving around his estate, finally decided to go into production with these specialty vehicles in 1929 using a Model A chassis.

From the Train Depot to the Suburbs

However, by 1951 a little over 20 years later, the world had changed. Fewer people travelled by rail, and the highway system was excellent, so driving vacations with the family became common, as did roadside motels. In addition to this there was the postwar trend of moving out to the suburbs and leaving the hustle and noise of the big city behind. There was even a sort of back-to-the-land movement in the early ’50s, and single-story “ranch homes” built on large lots were popular.

That trend was partly because many of the people raising families in the ’50s were fresh from the farm themselves, and though they did not miss the dawn-to-dusk backbreaking work, they did miss having a household garden and plenty of room to stretch out and enjoy life. And these were actually the people who created the golden age of the “station wagon.” Ford understood this trend more completely and called its mid-century offerings “Ranch Wagons” which—though a bit euphemistic— was a more apt description of the vehicle’s intended purpose.

Introducing the AllSteel “Woodie”

Gene Hofmann fell in love with his old Stovebolt wagon and purchased it a number of years ago, and even though it was showing its age, he saw its potential. He did much of the restoration himself, and acted as general contractor for the work he could not do such as the wood graining on the body.

Chevrolet made the transition to all-steel bodies and DI-NOC vinyl decals simulating wood graining in 1949. Actually they built both woodies and “tinnies” that year, but few people purchased the woodies. As a result, only 600 were built. And due to slow sales, the Hercules Body Company who made the wood bodies for General Motors, was ordered to send the surplus bodies for use on Oldsmobiles and Pontiacs. It seems by that time people were well aware of the attention wooden cars needed to hold up and look their best.

Going to stamped steel made the cars lighter, sturdier, and easier and less expensive to produce, but it did take away a bit from the richness and warmth of the natural varnished wood. And it also compromised the heavy car ride comfort. However, anyone who has owned a real woodie or for that matter a vintage wooden boat knows that you have to sand and re-varnish frequently to keep the wood looking its best. Also, wooden bodies were glued and screwed together, and with the vibration of daily use, they had a tendency to come loose and rattle and creak in rough service.

Restoring That “Wood” Appearance

DI-NOC, a 3M self-adhesive product, lasted a long time and gave the appearance of wood but when it aged it checked and dulled. Replacing DI-NOC would not be that foreboding if it were still available in the correct pattern, but there is little demand for it, so it is no longer being produced. But DI-NOC is still being used to create the appearance of wood in dash panels, and to simulate carbon fiber and other textures for automotive and architectural applications.

However, because the original correct DI-NOC is not available for this application, that leaves only one other practical alternative to preserve the look, and that is wood graining, as was often done on the dashes of many cars before the ’50s. There are still pros that can do this work, but it is expensive. Many of them learned their trade doing caskets, so you can still find people who know how to do it, but to do an entire station wagon would be a challenge.

And to do the job so the colors and graining look truly original and correct is even more of a challenge. But in the case of Hofmann’s wagon, a professional he hired came up with beautiful results. The inside window reveals and trim are still real wood, but the body is all steel. Chevrolet used Hercules bodies of white ash and mahogany for most of its woodies over the years, and that is what is echoed on Hofmann’s wagon. Ford, on the other hand, used a lot of maple because Henry had his own maple forest.

Built With Reliable Mechnicals

A vintage station wagon is somewhat like a modern so-called SUV, but the classics held a lot more cargo and people than what we have today. Granted, the classics were not designed to cruise at 80 miles per hour on the freeway, but our 1951 Styleline Chevy wagon will loaf along all day at 60 mph, which was five miles over the speed limit back when it was built. And in a pinch you could push the thing up to 75 if your life depended on it.

The 216-cubic-inch Stovebolt six that came in the standard-shift Chevys of the era had a long development cycle going back to the 1930s, and they were rock solid, reliable and smooth. Their cast iron pistons and thick, poured babbit bearings with splash lubrication were not intended for high performance. But within their design envelope they were longlasting and dependable.

Some people criticize the 216’s cast iron pistons as being too heavy, but iron pistons have a couple of advantages. One is that they could be fitted more precisely than aluminum pistons because they don’t expand as much in service; and the other is they wear like—you guessed it—iron.

Also, the thick, poured babbit rod bearings were not easy to replace (you usually just replaced the entire rod) but they had permeability, which was important years ago. You see, back when babbit bearings were commonly used, oil filters were the less-effective bypass type, and your car only sported one if you paid extra for it at the dealer or added it as an accessory. Thin-shell insert bearings could not absorb the contaminants that would get into your oil, so they would score and ruin the crankshaft. But the thick, poured bearings were soft, so grit would embed in them rather than score the crank.

The engine’s splash lubrication supplied plenty of oil to the rod bearings in normal service, and only became a problem if the engine became low on oil or you put the car into a very fast turn, which could cause the oil to slosh away from the dippers. Hudson also used splash lubrication until the 1950s, and they won stock car races routinely back then.

Chevrolets of this period also had closed drivelines which kept the back axle in place and avoided spring wrap-up, but made the driveline a bit more difficult to work on. Otherwise these cars were easy to service and maintain, and they gave years of dependable service if cared for properly. Chevy station wagons were set up just like the rest of the line except they came with one extra leaf in the rear springs to compensate for cargo, and that made the back end a bit firmer.

Power and Space for Its Purpose

Our station wagon is equipped with a standard transmission and a 4.11:1 rear end, but a two-speed Powerglide automatic was also available, and in that case it would have been powered by the 235-cubic-inch Blue Flame inline six that originally had been designed for use in trucks. Also, because it was only a two-speed, the differential for Powerglide-equipped cars was 3.55:1, which made for leisurely acceleration, but allowed a decent top end.

At 3500 pounds and with the same 215- inch wheelbase as the other Chevrolet models for 1951, the car is not that big and heavy, but it will easily accommodate eight people in reasonable comfort or six people and enough camping equipment for a trip to Yellowstone. It was just the thing for suburban family outings, as well as hauling gardening supplies and chicken feed.

The Woodie Era

It is interesting that while the station wagon concept goes back to when they were actually used as station wagons, such cars weren’t big sellers until the 1940s and ’50s. As an example, Chevrolet built just 800 wagons in 1939, but by 1955 they were producing 161,000 of them. I happen to own a 1955 Bel Air Beauville wagon, and though it was designed to serve the same family utility vehicle needs as the 1951 model, all pretense of a wooden body or even decorative wood decals had been dropped.

Actually, the golden age of the woodie was the 1940s. Chrysler built a number of station wagons, convertible coupes and fancy sedans using wood. And Hudson, Packard, Nash, Pontiac and Oldsmobile also built some handsome woodies. But Ford and Mercury probably sold more woodie wagons, sports coupes and convertibles than anyone else. And Chevrolet had a respectable segment of the market during the swingin’ years too.

We still called them station wagons, but they had morphed into something completely different by the mid-’50s. And from there the concept evolved further into Econovans, Greenbriers, minivans, and finally, SUVs. In fact the basic design concept was so successful that even Porsche and Cadillac are offering them now. And for a while, the Plymouth PT Cruiser, a retro-looking small SUV, could be ordered with DI-NOC faux wood side panels. It seems we have come full circle, even though few people need a lift to the train station anymore.

I’d Like to Keep It

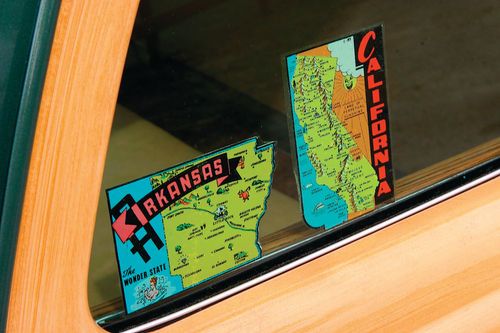

Our spin in the park reminds me how simple, solid and pleasant these classic utility vehicles were, and how life itself seemed simpler back then too. In 1951 people routinely took long-distance family vacations in such cars, and to point out all the places they had visited, they often purchased small decals and put them on their side windows. Nobody flew anywhere back then unless they were wealthy, and nobody took vacations without the family to accompany them.

The sun is starting to set, and it is time to get back to now, so the Hofmanns drop us off at my Saturn Vue SUV, that I would trade for a ’51 tinnie in a minute, even though it wouldn’t have air conditioning, turn indicators, a CD player or an onboard telenanny to tell me to turn left, then turn right in onequarter of a mile…