Readers Speak Out

We’ll Start With a Discussion on Roadsters vs. Convertibles, And Have Some Thoughts on Mules and Mopar Big Blocks.

Is That Car Really a Roadster or…

Hi Ted,

As a long-time subscriber and 74-year old gearhead, I would like your opinion regarding the difference between a convertible and a roadster.

As teenagers we were generally “aware” that a roadster had side curtains, while if a car had roll-up windows, it was deemed a convertible.

Furthermore, if an open car had four doors, it was called a phaeton. It seems that the roadster/convertible distinction has been lost over the years or, of course, there is the possibility I was misinformed.

Switch gears to the present and it seems each of my friends has a different opinion on the subject, some citing the number of seats or passengers as a criteria. Muddying the situation recently for me is a book on the development of the Mazda Miata which continually refers to the car as a roadster even though the windows roll up and down. Can you or your readers help?

Bob Urban Wahoo, Nebraska

I was brought up with the same definitions of roadster/convertible/phaeton that you have. But I think that with passing time the terms have all taken on a more generic quality and, as you pointed out, mean different things to different people. For example, I often have heard people, including veteran automotive journalists, referring to a Corvette convertible as a “roadster.”

All I can figure is that calling a sports car, such as a Corvette or a Miata, a “roadster” has a better connotation than saying it’s a convertible.

Another example that comes to mind is a Volkswagen luxury SEDAN, the VW Phaeton, that was sold here in 2004-06. How a sedan can be a phaeton eludes me, but it certainly does sound upscale, doesn’t it, probably in keeping with the car’s image and price tag. (I understand that the VW Phaeton sedan has been reworked and will return to the market around 2015. Reportedly, the next Phaeton will ride on the same platform as the upcoming Audi A8 and it will carry a number of aluminum panels to reduce the big car’s weight.)

In the final analysis, I guess terms like roadster, convertible and phaeton are something like the word “classic.” Most everyone has their own personal definition for that one as well.

If any readers want to speak out on the subject or any other auto-related subjects for that matter, Auto Restorer would like to hear from you.

—Ted Kade, Editor

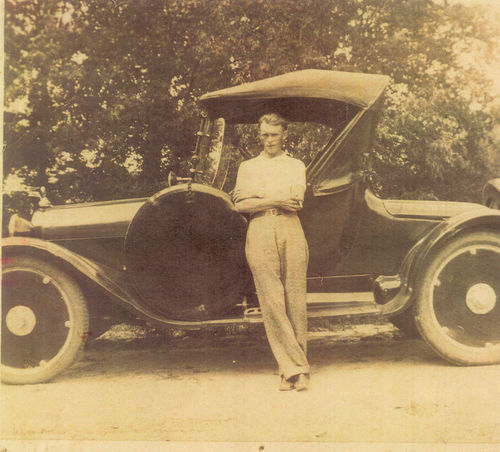

Regarding that Mysterious Car In the Photo…

The car in the December Letters section looks to be a Dodge roadster, 1920- 1923, with optional disc wheels and a side-mounted spare. The low hood says pre-1924, and the slanted windshield was introduced in 1920.

The key identifying feature for Dodge (for me, at least) is the bump-out on the front of the rear fender to give clearance to the spring mount.

Ron Mjos Provo, Utah

I believe the roadster pictured in the December Letters section sent by Alan Rivard is a 1921 or 1922 Dodge Brothers based on the high headlights, fenders appearing to have the raised center, turtle deck lid not flush with the body and the cover over the front of the rear spring mount. It also appears to have some modifications as I don’t recall ever seeing an early DB with a side mount spare and also a rear mount spare.

There also appears to be some type of cover on the wood spoke wheels to make them appear as disc type and the hub has been painted a lighter color so it appears larger.

Dennis Pitchford San Jose, California

We checked some photos of Dodge cars from the early ’20s and believe these readers must be Dodge fans to be able to home in on these 90-year-old vehicles. After staring at some photos of Dodges of that era, we’d say our pictured vehicle is either a 1922 second-series model or a 1923. The contour of the radiator, hood and cowl is higher on the 1922 second series than it was on the 1921 and 1922 first series, and seems to match that of the car in question. Furthermore, the 1924 Dodge cars had vertical louvers on the hood side panels, which are not on our subject car. That, of course, is a photo of the car on the previous page. (We have to admit, though, that we would have had a far easier time with, say, a ’56 Chevy, ’59 Ford or a ’64 Plymouth.)

Living With Mules

I’m really pleased to see your articles on vintage military vehicles; none more so than the September story about the military “Mule.”

As a Vietnam Vet (March ’69—January ’71) serving with the 1st Air Cavalry (Airmobile), and having the nominal MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) of 63B20 (wheeled vehicle repairman), I got my fill of Army trucks. Of them, the Mule and the 3/4-ton M37 (Dodge) truck were my favorites. Perhaps that was because I spent most of my 21 months there on forward “LZs” (Landing Zones) and Fire Support Bases (FSBs) and the largest vehicles we had most often were the Mule, with the occasional 3/4-ton.

I have to say the Mule stood out due to its utility, uniqueness (see my list of personal cars, I go for “unique”), and sheer fun. Besides the super-bouncy ride due to the balloon-tire suspension, the one thing that stands out most clearly was one of these mules rigged with an M134 mini-gun test-firing out from an LZ and clearing a swath of trees felled by the sheer volume of fire-power this weapon produces (2000-4000 rounds-per minute). This application to the Mule enabled the mini-gun to be deployed wherever needed on the defensive perimeter of the forward base (LZ or FSB), which for those with no clear concept of what that was, most often they consisted of little more than a clearing in the jungle surrounded with concertina wire and defensive bunkers. Sandbags, ammo boxes and culvert halves were our construction materials.

The other stand-out memory is of tipping these work horses (er, excuse me…Mules, so aptly-named) onto their sides in order to work on the undercarriage. It’s much simpler than using a lift or pit (which were non-existent in our circumstances anyway).

Just to round out the picture for those that may be interested, I did a quick random search on the Web and found a site with pictures depicting life on an LZ, complete with mules in service: http://www.webewebbiers.com/vietnam/ednoredstoryLZs.htm

By the way, great magazine. Keep ’em coming, especially the oddball stuff. Here’s my bid for vintage military vehicles and imports, both “new” (up to, say, 1983) and older.

Carl Hockett Santa Rosa, California

PS: My current stable includes: 1967 Datsun RL411 SSS (Super Sport Sedan, with R16 engine), two; 1969 Fiat 850 Coupe, two; a 1973 Volvo 1800ES Sportwagon; 1973 GMC Canyon Lands 260 MotorHome; 1973 Chevy C10 pickup; 1977 Chevrolet Nova; 1982 GMC S-15; 1992 Volvo 240 sedan; 2000 Daewoo Nubira CDX wagon and a 2003 (yes, a 2003, and an official GM vehicle at that) Daewoo Nubira SE wagon.

Former stable-mates include: a 1956 Chevy Delray 2-door post; 1957 Chevy Bel Air 4-door wagon (283, with twice pipes, slushbox, and 4-bbl. carb); 1957 Austin-Healey 100-6; 1960 VW bug; 1964 VW microbus; 1963 Studebaker Avanti; 1963 Datsun 320 pickup; 1964 Datsun 320 pickup; 1972 Chevy C20 3/4-ton service truck, with Service body and 2000- lb. lift gate; 1974 Fiat 128 wagon; 1974 Ford Courier mini-pickup; 1978 (Do I recall the year correctly now? You corrected me in a past letter in which I called it a ’77 Ford T-Bird with T-Top); 1963 International Metro-Mite; 1986 Cadillac Cimarron. And I’m sure I’ve forgotten a few others.

About Those Chrysler Big Block Engines From the ’60s & ’70s

The memories from my old buddy, Dave Erb, regarding big block Ford engines (“Readers Speak Out,” January) inspired me to say a few words about the Mopar big blocks of the same era. That was the period in which I was a J I Case farm implements dealer.

I used to run another brand of engine/cars and racked up more than 50,000 miles a year mostly on country gravel roads in pursuit of sales and the after sales servicing of the various Case machines. I won’t name that big block brand, but by 50,000 miles those engines were huffing and puffing leading me to trade every year.

Case used the 318 V-8 engine on the full-size combines (1010s) and after selling a hundred or two of them I came to realize we never ever opened one of those engines up! They were out in the field on the hottest days of the year. (I have a picture on my wall of a bank thermometer showing 122 degrees in a shady spot on a July day here in Fort Benton, Montana.) They ran at a governed 3000+ rpm in an atmosphere loaded with dust and chaff pulling through soft dirt and steep hills and like that drumming rabbit in the ongoing advertisements, they just kept on running.

Later Case came out with a 25% bigger machine and they were equipped with the 318H which I gather had higher compression—the only way you could tell the H over the 318 was the spark plugs had about 3/4” more threads.

The only service call I ever made on any 318 was for a customer, more than irate, who said the engine could hardly move his combine much less cut any grain. I jumped in my Cessna 182 and was at the gent’s place in about 30 minutes from the call and he was 60 miles from Fort Benton.

Mercy, he was upset.

He assured me that they had just changed the oil, so no need to look there! I pulled the dipstick anyhow—lo and behold—oil spouted out of the dipstick hole. I know for sure it had a double dose of five quarts of oil and considering how much came out; I think maybe it was three doses.

That operation included a father and two sons and I do believe each in turn had given it tender loving care.

It really spouted blue smoke and never got up to speed. But it ran much better with less oil.

A Big Block of My Own

Then the light bulb finally went on in my head “Why don’t I drive those engines?” My first big block was a 413 cid Dodge. I can’t help but comment that the truck had the sweetest transmission I ever met in a truck—a five-speed with a two-speed rear end. By splitting gears each one all the way to the top there was a 500 rpm change.

We did have to overhaul that engine but it wasn’t the engine’s fault.

A small screw came out of the carburetor’s butterfly somewhere in North Dakota and by the time I got it home, that screw had beat the heck out of a piston. There must have been a tremendous compression ratio judging by the fact that a tiny screw did all that damage. I suppose we put 250,000 miles total on that engine and when I went to a unit with a 6-71 GM diesel; I actually sold the Dodge for more than I paid for it.

(Ah, the days of instant inflation—I fear we shall see them again shortly!)

From a Truck to a Car

My first big block Mopar in a car was a Chrysler wagon with that dandy rear door that would hinge out or drop down level with the interior. That first one was a 400 cid. I think we put about 150,000 miles on it when my accountant said I needed to get some depreciation. That was quite an automobile!

I sold a gent a big 4-wheel-drive Case about 200 road miles from Fort Benton. Then the Case Co. discovered a flaw in that tractor’s planetary hubs and directed an immediate replacement.

They had four 750# hubs air freighted to Great Falls. Our Dodge Pickup was out on another service job so we picked up the hubs with the station wagon.

We had lots of air in the car’s tires and the nose was aimed rather high and we were not interested in crossing any highway scales.

I had my wife take the car while I flew my shop foreman to the customer’s landing strip and we pulled those four wheels with eight big tires loaded with calcium solution, tore down all the gears and pins and shafts inside and at the last one, as my foreman was wiping his hands, he commented, “Where are the new hubs?” Just then my bride drove over the hill.

The farmer’s wife fed us all a big lunch; we swapped the old hubs for the new ones in the Chrysler and sent my true love on her way. We put everything back together, took the tractor for a test pull and still beat my wife home by about an hour. Those wagons were way underrated for tonnage capacity.

A Big-Block Family Affair

After awhile, times got rather tough in the implement business. I saw the end coming so my last new Chrysler was a sedan. After that, I bought used ones. There was one for each of my three kids when they headed for college, and one for my wife who began making 300-mile trips every other week for years for family reasons. That car—a 440 brougham— said 79,000 miles on it when I bought it. I would never question a car salesman’s integrity but the brake pedal sure looked like it had more miles than that. Anyhow, my wife drove that until the speedometer turned over the century mark twice.

One day she came home rather excited and said “there is a red light that says ‘OIL.’ I drove it about 30 miles that way. Was that wrong?” For ye who succor a big block Mopar, I suggest you pull the oil pump and have a look at the relief valve tube. The relief valve had worn a groove so deep, the piston stuck open. I had the same thing happen to a son’s high-mileage 400 engine. In her case we had to tear it down. The amazing thing is the crankshaft was perfect after 205,000 miles. We re-bored and the valve guides were wiped out but that shaft went back in with standard inserts. That one high volume pump saved rod bearings on both ends. My son stopped his car in time and all we did was put in a rebuilt pump. His ’76 Chrysler 400 went from here to Chicago for numerous trips pursuing his MD-Ph.D. and finally on to California where the company he joined said they were embarrassed for him to be parking that thing where the public could see it! They felt that it made it look like they were underpaying him. So he bought a new Chrysler convertible and all was well.

We helped move a son to a Chicago med school. He had a ’77 Newport with a 400. We had a ’75 New Yorker with a 440 Lean Burn. The latter was supposed to give way better mileage over the standard. Both cars were loaded heavily. It was 1500 miles and we were together all the way. Both cars averaged 18.5 mpg. In fairness that was when we cruised down the road at 55 mph. My 2007 300C averages about 25 at 75-80 which is how fast we drive in Montana.

Some Tips for Mopar Big-Block Owners

For those with big blocks there are several things that can displease you. As mentioned above, if your engine is beyond 100,000 miles, check that oil pump. It’s real easy! Pull the distributor cap and mark the angle of the rotor on the distributor body. One bolt and you can pull the distributor. I think there are four bolts on the oil pump and it will slip right out. Rebuilt units are relatively cheap.

The timing chains have a nasty habit of wearing out. I have seen them cut a hole in the timing cover from a broken link and I have seen them fall clear off which is not a good thing. You can change them by just pulling the fan unit and the crossover water manifold. Change the water pump hoses while you are at it. Two pumps and a chain every 100,000 miles or so isn’t a major expense.

The valve cover gaskets can be a pain. The exhaust manifolds are about 3/4 of an inch from those gaskets and they cook out. The best luck I have had is to use Permatex Ultra Black. It is a rubberlike compound in a pressurized can.

My family and I ran those big blocks for about 30 years. I accumulated all kinds of used parts and right now I have three of the cars. I am a rather high priced tradesman and my customers didn’t think much of a guy driving a ’77 Chrysler and charging my usual fees. I keep a ’75 licensed and insured for my friends who think it is like riding on a living room couch, and I have a couple more on blocks. I gave one to the local museum and my wife now drives a ’97 LHS. Viva Chrysler!

—Richard Cassutt

Name That Hub

In November Jim Huff of Huff’s Auto Body in Asbury, New Jersey, sent in the photo of the antique hub seen on page 21 and said he didn’t know where it came from, but it had wood spokes, a chain sprocket and no markings on is cap. So we asked for help from our readers and received a response from Richard E. Summers of Pompano Beach, Florida. Here’s what Richard had to say:

“That hub on page 5 of the November issue looks like it comes from the rear wheel of a 1920s era or earlier Mack truck. Those trucks were chain drive and rode on solid rubber tires.

“Tootsie Toy made a model of it in the early 1930s. It had the distinctive Mack hood and a rough detail of the chain drive on the casting.”