Engine report, the Chrysler (Mopar) 440

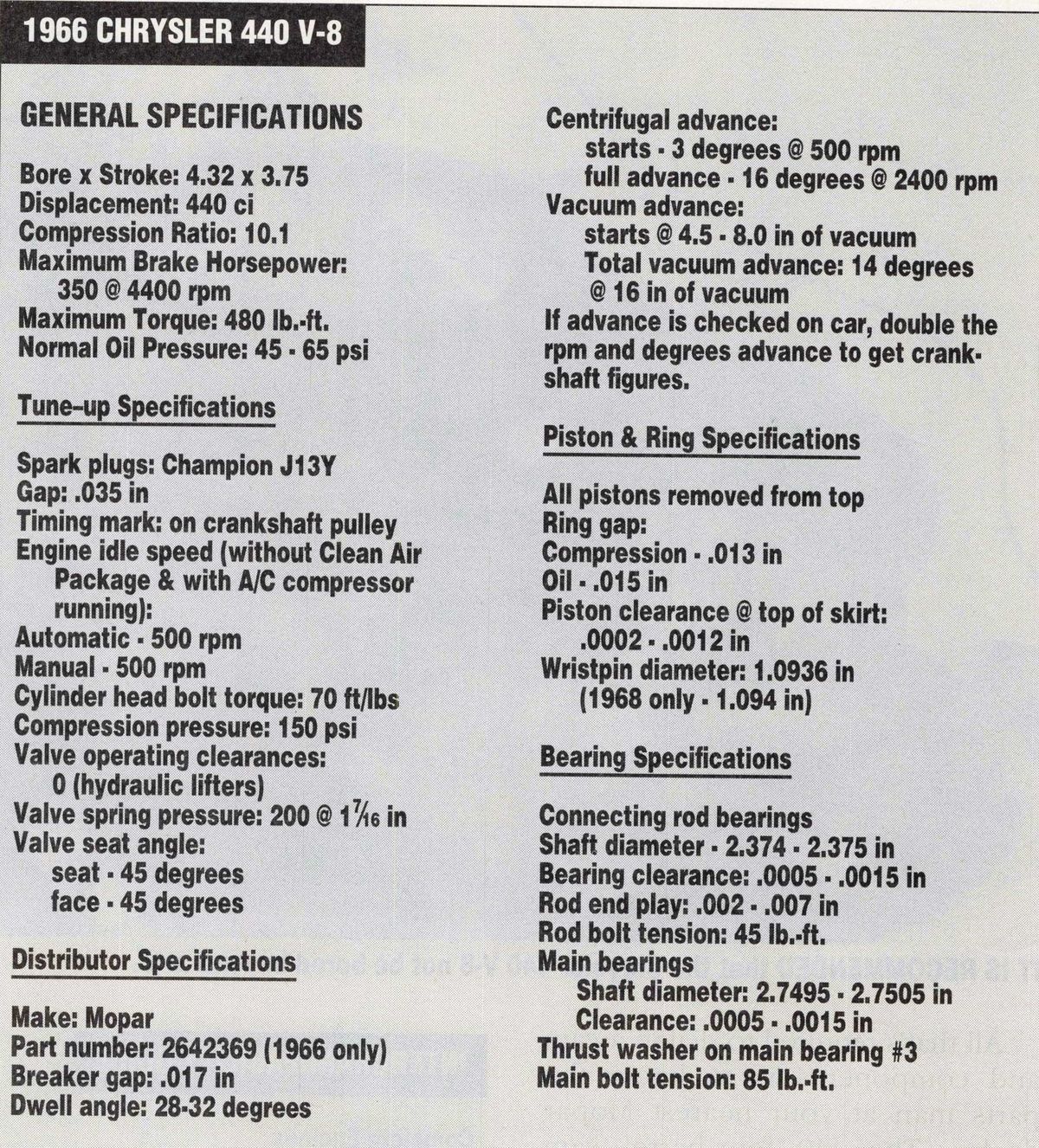

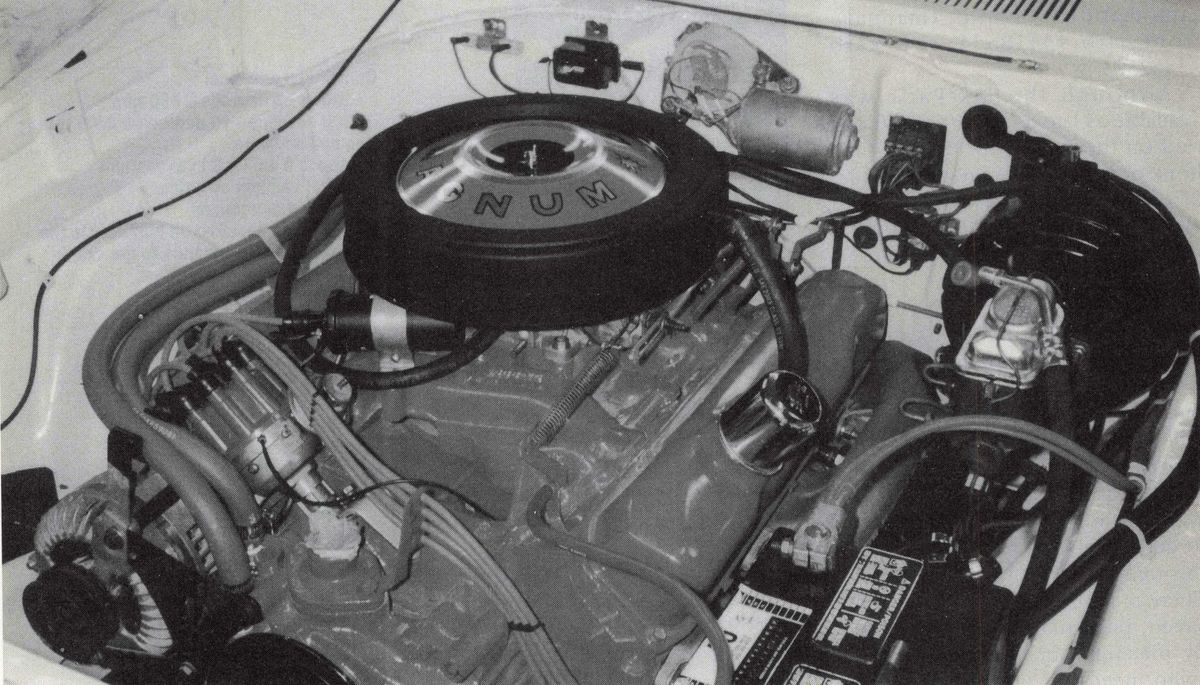

1966, Chrysler installed the first 440-cubic-inch engine into its big cars: the Dodge Polara and Chrysler New Yorker. The engine carried the “RB” code, an abbreviation for raised block — the long-stroke version of the “B” block previously used in the 361-cubic-inch engine. The original 440 was rated at 350 horsepower, which was a bit overrated. It made do with a mild cam, heads with small ports and a single exhaust. Sheer size made up for any deficiencies in horsepower. Its 480 lb.-ft. of torque, down low in the rpm range at 2800 rpm, indicates the intent as a highway hauler with plenty of power to move large families with boats and travel trailers. Things changed significantly in

1967 when the 440 became the beneficiary of free-flowing heads, a high-performance cam, a set of low restriction exhaust manifolds and dual exhausts. On top was a four barrel Carter AVS (after 1972 a Thermo-Quad) carburetor. Horsepower soared to a claimed (but underrated) 375. Maximum torque still reached 480 lb.-ft., but now it was peaking at 3200 rpm.

The new engine appeared in two new Dodge and Plymouth models, the Coronet R/T and GTX respectively. The engine could also be optioned in many other Chrysler products instead of the cookie-cooker 318 or the medium performance 383.

The top performing model was the 440 Six-Pack introduced in 1969 on the Road Runner, Super Bee, Challenger, ‘Cuda and GTX. For those who are searching for proper Six-Pack set-ups the part numbers for the carbs are: center carb #3418550 (automatic), #3418549 (manual); front carb #3418554; rear carb #3462373.

Although the Six-Pack was available as late as 1972, the 440 carried on through 1978. By that time horsepower had been reduced to 255 (determined as a net rating with all accessories attached) and torque was only 360 lb.-ft. at 3200 rpm.

Problems

The key to restoring a 440 and expecting a long engine life is to start with the right components when rebuild time comes around. It is important to know that some model year 440 parts are stronger than others. Whether it’s a 1966 or 1978 car, you won't have to pay through the nose to get top quality replacement parts through your local Mopar dealer. There’s really little money to be saved, particularly in the long run, by piecing your 440 together from swap meet bargain bins or salvage yard remnants. Build it right and reliability and performance should be at your beck and call unless you plan to punish the engine with trips that are rarely longer than a quarter mile.

Cylinder Heads

When the “B” engine was introduced in 1958, it was built in 350- and 361cubic-inch versions. Numerous head castings have been produced for the “B” series and then the “RB” series engines (413, 426 and 440). With the introduction of the Stage V, Stage VI and B1 racing heads, during the past 10 years, there are more than 17 different head styles available.

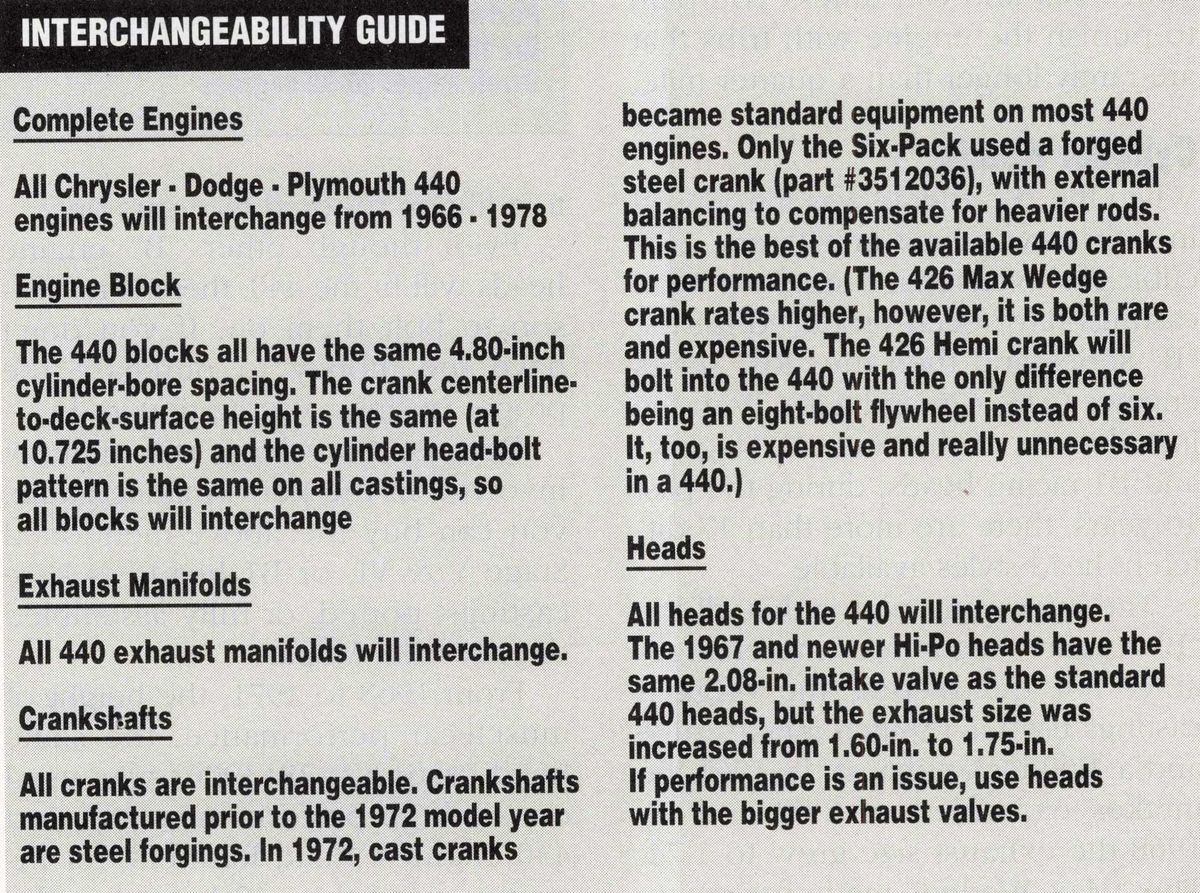

The interesting part is that all the “B” engine heads are interchangeable. For the record, the original castings used a 1.9-inch intake valve and a 1.00-inch exhaust. In 1961 the intakes expanded to 2.08 and by 1968 the exhaust size grew to 1.74. The “Max Wedge” made-for-racing heads created the biggest noise in 1962 when they maximized the output of the famous 426 wedge block engine. Only the introduction of the high-performance heads in 1967 enabled the 440 to steal the thunder from the legendary Max Wedge. The scarcity of Max Wedge heads has pretty much relegated those treasures to a life on restored race cars only.

Even though other “B” engine heads will fit the 440, there is no reason to bolt them on. If you don’t have the money to purchase the proper castings, wait until you do.

Because Chrysler is still mightily involved in the performance game, you can buy the above-mentioned Stage V & VI, or B1 heads as bare castings, ported, or fully assembled directly from Mopar.

From 1968 to 1971, the height of musclecar performance, the same head casting (#2843906) was used on all high-performance 383 and 440 engines. Road Runners, for instance, used the 440 heads on the 383 engines.

To combat the smog monster in 1972, Chrysler changed the casting to one with a flatter intake port for better emissions control. At the same time, compression dropped from 10.5:1 to 8.5:1 and horsepower began its downhill ride. For building an engine with performance in mind, stick to the pre-1972 engines, or find a set of heads off a post-’72 police car.

All cylinder heads must be inspected for flaws before use. Although mistakes such as sand in the casting are rarely found, you need to check for cracks around the guides and near the head-bolt holes. Be sure and have a good valve job done, facing the seat with a 45-degree angle, and use new seals, valve locks, retainers and related parts.

Valvetrain and Cams

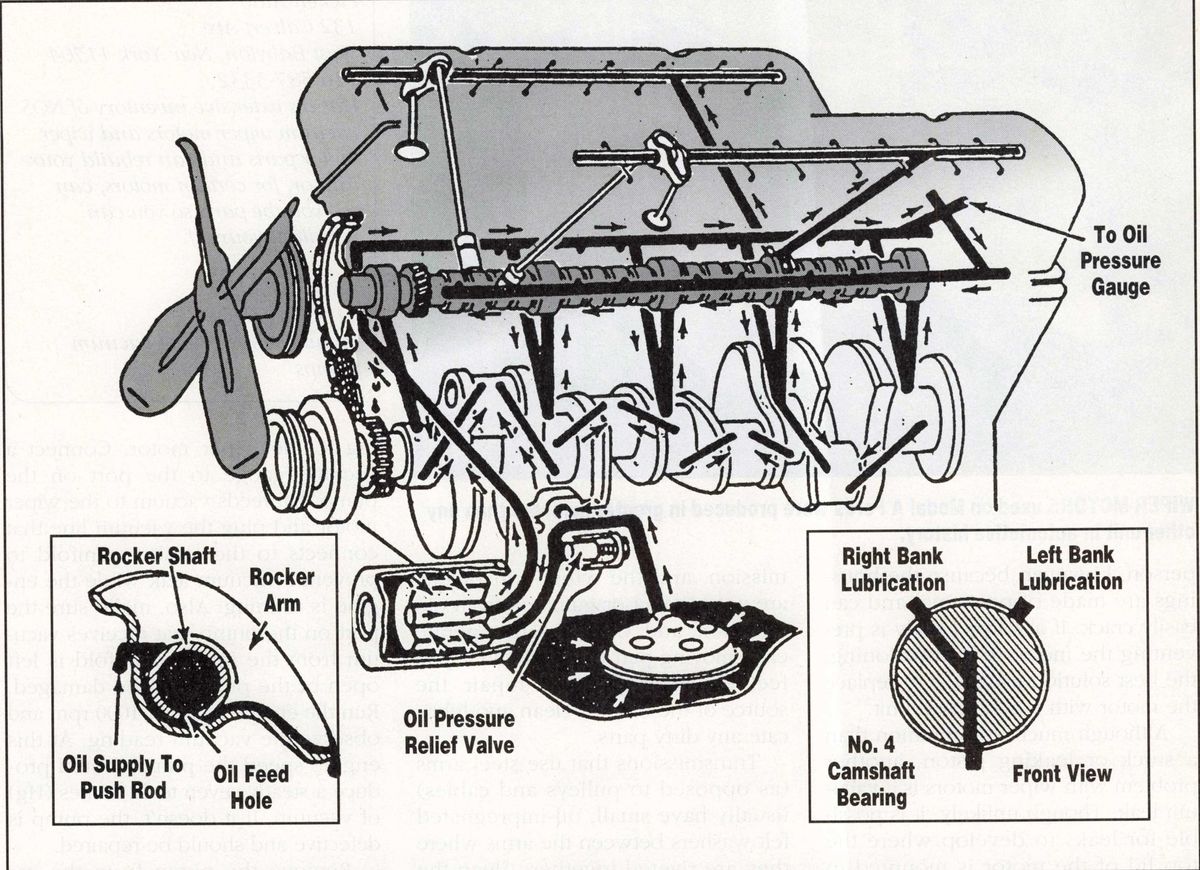

Here’s where life gets interesting. Because many Chrysler big blocks have been raced and continue to be raced, the choices of cams, valves, lifters and all the related parts are virtually unlimited. There is no reason to put a used cam back in a rebuilt engine. Mopar offers “Purple Shaft” (named after a dot of purple paint on the shaft) cams in a full range from hydraulic restoration grinds to race only roller cams with stairstep-sized lifts. All that’s required to dial in a cam and components is to know the parts man at your nearest Mopar dealer. The 440 four-barrel cam grind has 268 degrees intake and 289 degrees exhaust duration with .450 in lift. This cam will do wonders for waking up your engine and still have all the street benefits of smooth idle, low down torque and a very broad power range.

The next step up is one of the Purple Shafts with the Street Hemi specs. Intake and exhaust are 284 degrees and lift is .471 intake and .474 exhaust. Overlap is 68 degrees, so idle will be a little rough, but still within acceptable means in a Road Runner, Coronet 440, Super Bee or the like. For a Chrysler New Yorker or other big car, stay with the Mopar stock cam still available through the dealers.

Pistons and Rods

The Chrysler “RB” blocks use a cast aluminum piston with steel inserts in the piston pin boss area. These inserts hold the piston in the expanded position it would assume when hot. I recommend these cast pistons for engine speeds up to 6000 rpm. Most aftermarket cast pistons should be avoided, unless they are going in an engine that will not be asked to deliver performance. The factory cast pistons are a great deal more expensive than aftermarket cast pistons, however, you will get what you pay for when it comes to piston strength. They will provide long street life and are able to hold up under some casual racing with no problems.

If the engine is going to be used primarily for racing, forged pistons must be used. The factory offers a TRW-designed forged piston with an 11.0:1 compression ratio in .030 and .040 oversize. My sources ‘say 440. blocks shouldn’t be taken out more than .040-inch in order to maintain reliability. The block can take a .060 punch and there are pistons made for this size, but a .060 overbore can lead to bore distortion problems and a decrease in performance.

Forged pistons are much stronger than cast, however they do run noisier in the bores. They also allow more oil past the rings than a cast piston. If you want the ultimate in strength and don’t mind increased oil consumption and a noisier engine, then forged pistons are the way to go.

Choice of rings is easy. Stick with Mopar parts when you run cast Mopar pistons. Use TRW-type rings with forged pistons. Most aftermarket piston manufacturers provide rings matched to their products; stick with their recommendations.

Rods are the one area where you have to be more careful when it comes to selecting parts. The stock passenger car rods used in the 440 engine (Part #2406770) are adequate for an engine that won’t see more than 5000 rpm. However, don’t use them for any performance application.

In 1970-71 Chrysler fit its 440 SixPack engines with a high-performance rod (Part #2951906). It was a special forging with a wider beam section from the big end to the pin. This rod also found its way into the 1971-73 440 four-barrel engine found in numerous trucks and police cars. Now that the source of old police pursuit cars has about dried up, the other place to look for a rebuildable engine core with the stronger rods is in salvage yards that specialize in trucks.

Building an engine for quarter-mile bursts requires a stronger rod. Once again, Mopar has done most of the hard work for you. Part #P-3690649 is a magnifluxed, polished, high-quality forging, doubleshot-peened for maximum crack resistance. Mopar Part #P-2531589 is a Hemi rod with the center-to-center length modified to the RB spec (6.768 in.). This rod uses “o-inch bolts as opposed to the standard %-inch bolts found in 440s. It also is strengthened in many of the high stress areas.

If you decide to use the rods from the engine undergoing rebuild, here are a few items to examine:

Make sure the rods are straight. A bent rod can be straightened, but for the cost of a new set, I'd throw out the old ones. Yes, even on a budget rebuild.

Check the big end for roundness.

Pay particular attention to the rod bearings from the old engine, any signs of side-wear or distortion indicates a bent rod.

When planning a rebuild, put your money in the bottom end — rods and crank.

Take the time to properly set-up clearances.

Use a good brand of bearings (Michigan 77 comes to mind).

Break the engine in slowly.

With no more than routine maintenance, it should last until you're tired of looking at it.

Crank

When considering the replacement of the crankshaft, I have a few more tips that you should keep in mind. Always check the main-bearing bore and general bottom-end integrity, if working with a used block. Make sure the main bearing caps have been replaced in the proper order and in the proper direction. More than a few engines have had the cap installed in the wrong direction, or in the wrong place. Once discovered, everything has to come apart because metal has been shaved off the cap and block; it is probably stuck in the bearing.

All pre-1972 cranks were steel forgings and failure was very rare. Occasionally the third main bearing would spin, so pay particular attention to that area. Most 1972 model year and newer engines had cast iron cranks. Only the Six-Pack engines didn’t. The cast iron cranks make wonderful boat anchors. My recommendation for a replacement in a street/strip car is the Six-Pack crank.

All the cast cranks and a few forged ones were externally balanced. This means an eccentric-balanced vibration dampener, torque converter and flywheel were used to

balance the rotating mass. If an internally balanced crank is used with any of these components, the engine will vibrate like a jack hammer and be impossible to drive. A quick way to identify an externally balanced crank is to check the harmonic dampener for an eccentric weight.

A good choice of crank for a restored engine that will be for mild street use only is part #2536983. For competition and street running, go with #3512036, the Six-pack crank. For top performance, buy a 1053 steel forging new from Mopar.

Tech Tips

Let's say you have a 1965 Road Runner with a 440-cubic inch, 375 horsepower engine. Everything from the fan blade to the rear axle nuts has seen 100.000 miles of use. With a budget to spend on rejuvenating this unit. what can be done and how would you prioritize it?

My advice is to invest your money in the engine and drivetrain first. These are the thing you only want to do once. After the engine is restored, then work on the rest of the car. The absolutely necessary items on the list should be:

Rings

Bearings

Gaskets

Steel timing chain

Cam bearings

Additional items that should be checked and replaced if worn or damaged include:

The entire valvetrain: valves, springs, keepers, collars and lifters

Camshaft

Pistons

Rods

Machine shop work would include:

Magnaflux the block and crank

Bore or hone the cylinders

Check the align-bore of the crank

Complete valve job