His & Hers Country Squires

They Like Vintage Drivers But Weren’t of a Mind to Perform Complete Restorations. Here’s the Approach They Took.

Regardless of practicality matters, in the 1960s woodie wagons with genuine wood became very affordable and somewhat popular for younger car buyers—at least for those involved in the surfing culture.

As a result, today such cars are often displayed at auto shows with a surf board affixed to the roof or sitting in the cargo section projecting through the open tailgate window. Even wagons with fake wood can be considered a “Surf Wagon” such as the 1968 Ford Country Squire seen on these pages which is owned by James Buie of Diana, Texas.

Buie found the car by chance about five years ago when a friend invited him to browse through some items offered for sale in Alba, Texas. He found this Country Squire sitting behind a barn. With the $500 asking price, James knew he could not go wrong in buying the car.

James’ Country Squire had been scheduled to be built at the Dallas assembly plant very early in the model year—Aug. 29, 1967—but was not actually built until November 16 according to the Deluxe Marti Report from Marti Auto Works. The reason for the change in the build date is not known. Strangely, the car was to be built with the FMX automatic transmission, but instead got the C6 automatic. Perhaps that had something to do with its lengthy assembly delay.

His car was ordered with several other extra-cost items including the 390 2-bbl., power disc brakes, power steering, wheel covers, remote-control outside rear view mirror with matching passenger-side mirror, roof-mounted luggage rack, tinted glass, and the “Convenience Group” which consisted of warning/reminder lamps for seat belts, door ajar, parking brake and low fuel. It was sold new on December 5 at Horn and Williams Motor Co. on South Buckner just a short distance from the assembly plant.

An investment of an additional $4500 over his purchase price got this Country Squire functioning as a reliable driver. James elected to not perform a serious cosmetic restoration on his station wagon, but did clear coat the faded paint to arrest further deterioration. Over the decades, leaves and other debris had collected in the lower doors and quarter panels which blocked their respective drains, thus leading to rust-out, but not to the point of losing structural integrity. These areas were cleaned, but no sheet metal work was performed.

Since rebuilding the mechanical systems, he and his wife, Debra, have driven the car on three Hot Rod Power Tours (2012, 2013 and 2015) and have received several awards at various car shows.

Some Country Squire Background

From 1950 to 1991, the Country Squire represented the top-of-the-line in Ford’s station wagons and they were instantly identifiable by their standard wood body structure and trim at first or the application of simulated wood paneling that followed.

In its original guise, the Country Squire was a two-door model, but beginning with the 1952 model year it became a four-door and would remain so for the duration of its production. Also that year, the all-steel body received Di-Noc inserts to simulate the appearance of wood paneling. Surrounding trim remained wood for a while longer until finally being replaced with fiberglass, also with simulated wood graining.

The Country Squire was a descendent of the early station wagons constructed as wood bodies with a steel cowl and front end. They were beautiful when new, but needed constant care to keep the wood preserved—something which was seldom done. Periodic re-varnishing of the wood was not a convenient chore. Eventually, faux wood offered a much cheaper alternative, proved much more practical and provided the appearance of beautiful stained wood— or at least it was close enough. With this change came lower prices and higher production of the Country Squire.

Each generation of the Country Squire was updated as often as the rest of Ford’s full-size model lineup. Model year 1965 brought the first total retooling of the full-size bodies since 1957—even the keys were advertised as new. The basic design continued to be used through the 1968 model year. However, new sheet metal was introduced each year to refresh the look of Ford’s cars and 1968 was no different. Adverting promoted the new Fords as being “quiet, strong, beautiful.”

Model Year Changes

The annual model year updates differentiating the 1968 from the prior model year once again resulted in a large number of one-year-only components including most sheet metal, grille, headlight surrounds, tail lamps, bumpers, emblems, identification script, dashboard layout, steering wheel and other items. The same had happened with the 1967 models.

Among the changes for 1968 was a special grille with hidden headlights for the top-line models (LTD, XL and Country Squire), a bodyside crease following the sweeping curve of the quarter panel, and revised tail light assemblies. Interior changes included a flat, wide crossbar-type steering wheel and redesigned steering column to better absorb impact during a crash, new instrument panel, updated upholstery pattern, etc. Another safetyminded change was the introduction of shoulder harnesses as standard issue beginning in January. Standard equipment for the Country Squire consisted of the 302 V-8, three-speed manual transmission, heavy-duty suspension, die cast grille, “Limousine-Luxury” pleated cloth and vinyl upholstery, electric clock, woodgrain accents on dash and door panels, and wheel covers. Additionally, buyers had a choice of a six-passenger version and a nine-passenger type with dual-facing rear seats. Furthermore, the 302 became the standard engine for the Country Squire, replacing the 289.

Optional equipment included a 390 2-bbl., 390 4-bbl., a 428 4-bbl., automatic transmission, power brakes (standard on dual-facing rear seat wagons), power steering, AM-FM radio, air conditioning, tinted windshield or tinted glass, split bench seat with fold-down armrests, two wheel cover options and cruise control.

Performance figures for a big block 1968 Country Squire are not readily available, but one can get a good approximation through the contemporary road test report on the XL hardtop published in the January 1968 issue of Car Life. Their 4568-pound test car equipped with a 428 and automatic transmission along with a 2.80:1 axle ratio required 8.2 seconds to reach 60 mph from idle and covered the standing start quarter-mile in 16.68 seconds with an end speed of 87.3 mph.

Concentrating on Mechanical Systems

James performed plenty of mechanical work to make his wagon a reliable driver and made a few changes in the interest of comfort and cosmetics. His goal was not a high-dollar restoration, but simply to arrest the deterioration and make the needed repairs to have a reliable driver.

One of the earliest projects was to rebuild his car’s original Y-code 390 2-bbl. The rebuild, done locally, included a .030 overbore and a performance upgrade via a Holley 770 Street Avenger four-venturi carburetor, Edelbrock Performer aluminum intake, Comp cam, double roller timing gear set, Hooker long-tube headers, Mallory distributor, MSD ignition, and a high-flow aluminum water pump. Exhaust exits through three-inch duals. Later he added the appearance of a blower by cutting an opening in the hood for the air intake system used with a supercharger and attached it to the carb. A K&N filter was placed inside the scoop and the linkage for the butterfly valves was connected.

As for the transmission, the car’s original C6 three-speed automatic was also rebuilt and upgraded with a TCI 2500 stall converter and shift kit.

Ford’s nine-inch rear end was well designed and has a reputation for durability and since it was functioning just fine James did not need to repair any of its components; the original 3.00:1 gear set was left in place.

Handling for the full-size wagon was not up to James’ standards, so he added an aftermarket sway bar to the rear end. “It really made a big difference,” said Buie, “and it bolted easily to the trailing arms.”

Frame Evolution

Starting with the ’65s, Ford employed an all-new perimeter frame with reinforced cross members. It was not simply a new frame, though. In the prior years, the frame was designed to provide complete beam and torsional strength. The frame was somewhat flexible while the body was designed to be much more rigid than in the past. This concept in combination with plenty of sounddeadening insulation provided a much quieter riding car.

The new frame design incorporated a front end assembly, rear end assembly and straight box-section side rails. Torque boxes welded at each corner of these side rails joined the front and rear units. These torque boxes allowed a limited amount of flexing plus dampened noise and vibration that would have otherwise been transmitted to the frame through the suspension system. The design is known for rust-out around the torque boxes, but for cars used in dry regions, away from coastal areas, and away from locations where the roads are salted to melt snow, this is not a problem area. James’ Dallas-built car has been a safe distance from such places having stayed in the North Texas area.

Three basic frames were used—one for sedans and hardtops, one for the convertibles, and the other for station wagons.

The convertible frame did not have an X-member as in the past. Body attachments were at only four points— just ahead of the cowl and immediately behind the rear passenger area. Rubber biscuits were installed between the body and frame side rails. Other than contributing to a quieter ride, the frame also had the virtue of being much lighter than the earlier version.

Along with the new frame was a new suspension. The lower A-arms of the independent ball-joint front suspension were replaced with a single arm; the upper A-arm was retained and was angled back to reduce brake nose dive; a diagonally mounted, rubber-bushed strut was employed to control fore-aft wheel movement; an anti-roll bar reduced body roll during cornering; shocks were placed within the coil springs. The design of the front suspension was so superior it was used for NASCAR stock cars into the 1980s regardless of make.

A three-link, coil spring suspension was employed in back. The longitudinal links controlled fore-aft motion of the rear axle assembly and absorbed acceleration and braking forces. Two of these links were positioned between the lower side of the axle housing and the frame torque box at either side. The third link was installed between the right-hand side of the differential at the top of the axle housing and the frame crossmember. A track bar was attached near the axle center and to a lateral point on the frame left rear rail. The rear suspension was fully isolated with rubber bushings and sleeves which served to further reduce noise and vibration transmission.

James’ car needed only new bushings in front to restore the original ride. Replacement suspension parts are still readily available through retail auto parts dealers (in this case through O’Reilly Auto Parts), though upgraded polygraphite bushings are sometimes preferred by restorers; these can be bought through restoration parts specialists. Buie opted to retain OEM-type equipment.

Steering & Brakes

All Fords received a new parallelogramtype steering linkage with a cross link and idler arm for more positive vehicle control under all driving conditions.

A valve-type power steering unit integral with the Magic-Circle steering gear and a new belt-driven power steering pump were additional advances from ’65 which were carried forward. Once again, the restorer has the advantage of readily available replacement parts for the power steering system.

A total rebuild of the power-assisted disc brakes renewed the stopping power of the big Ford which was reasonably good by the standards of the day. Some restorers opt to upgrade the brakes of their car with power disc kits. Discs, of course, offer much higher fade resistance in heavy braking conditions, but are not especially necessary unless highperformance driving or hilly terrain is a consideration. A dual master cylinder replaced the single-reservoir system starting with the ’67 model year.

A set of 15x8 rims were powder coated bright red and fitted with 245/60x15 BF Goodrich radial TA tires and bright trim rings provided some colorful contrast and a sporty flair. The factory wheels and wheel covers were put in storage.

Working With the “Woodgrain”

As noted earlier, the original Wimbledon White acrylic enamel paint and patina received a clear coat to arrest further deterioration. Sun-dried and bleachedout original faux wood remains in place. The woodgrain panels could be replaced with aftermarket vinyl closely matching the appearance of the original material. Most of that new vinyl, however, is not stable under ultraviolet light exposure, so it is not especially durable. Around five to seven years is about the life of it with regular exposure to sunlight. The 3M Co. marketed the OEM Di-Noc, but new 3M material is not known to be particularly superior in resistance to fading. By the way, the original Di-Noc on these wagons is not simply woodgrained. There are ¼-inch-wide horizontal black lines in it spaced about four inches apart on both the 1967 and ’68 Country Squires. However, restorations without these lines are not uncommon.

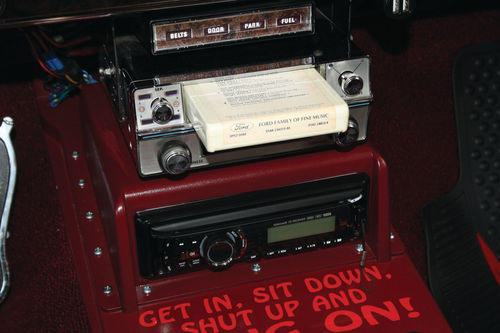

Going inside, most of the interior is original. The front bench seat was worn out, however, so James found a use for a set of red bucket seats purchased from an estate auction some time before he bought the wagon. Some of the seat anchors aligned perfectly with the original factory holes, but where they did not James drilled new holes and added some reinforcement with sheet metal since that is what Ford did around the factory attachment points. The original dash pad was a bit too worn, so it was replaced with an NOS part bought on eBay. A home-built console sits between the bucket seats and houses a modern stereo and a period-correct 8-track player.

A Country Squire for Her

Sometimes when the totally unexpected happens it is a very good thing. Such was the case when James and his wife, Debra, attended an auto show at the Texas Motor Speedway just outside Ft. Worth in 2013. Neither was contemplating the purchase of another car that day.

Just before departing James and Debra strolled over to the swap meet area to browse the cars for sale. Among them was a Springtime Yellow 1967 Country Squire with 79,000 miles. It was sunfaded, but was still wearing its original paint and upholstery.

Debra liked the car, so James made an offer which was acceptable to the seller—but there was one hitch. He had not planned on buying a car, so he was not carrying enough cash and the seller wasn’t enthusiastic about accepting a check along with some cash. Then fate intervened in a most unexpected and unusual way. Also present at that moment was Richard Rawlings of the famed Gas Monkey Garage in Dallas. He had observed the negotiations and upon realizing the deal was going to fall through made an offer $100 below James’ and in cash. The seller accepted.

By this time a crowd had gathered having recognized Rawlings from his TV show, “Fast & Loud.” Rawlings then turned to James and said, “Work out the title, drive it home, and bring me the money you were going to pay for the car on Monday.” James was almost speechless, but said something like, “You don’t even know me.” But that made no difference; Debra got her car.

The following Monday, James and Debra traveled to the Gas Monkey Garage in their ’68 Country Squire to pay for the ’67. After settling up, the couple got to tour the facilities and Rawlings also signed the dash on James’ car. Richard Rawlings had gambled thousands of dollars on their honesty all for a profit of $100! When James asked why he took the chance, the answer was, “You two had GMG (Gas Monkey Garage) hoodies on—how bad could you be?”

Not long after the purchase, James began making the few repairs needed on his wife’s Country Squire. It already had new tires; simply replacing the front suspension bushings and a tune-up kit got the nearly 50-year-old car ready for the road and some local car shows.

So Maybe It’s Not a Concours Contender…

In the case of each car, James has shown that for those who are not purists and/or do not have the money to spend on a complete restoration, the choice of making a car mechanically sound can be another way to enjoy a vintage driver. Tell us, readers, have any of you taken this approach?