Feature Restoration 1972 Mercury Cougar XR-7

With Time, Badge-Engineering Grew Between Ford & Mercury. The Cougar Was Different…and That’s Nice.

THERE’S NOT A hobbyist in the world that hasn’t left his phone number with the owner of a car that wasn’t for sale and pinned his hopes on a change of heart. Usually, it results in not much more than a good story to tell, but every now and then…

“I bought it from the original owner about 13 years ago,” said Ed Mance, whose 1972 Mercury Cougar XR-7 convertible is shown here. “Being on the road as an insurance adjuster, I found the car because I had a claim with him and he had to show me his cars. He had some later-model Mustangs—Fox-body Mustangs—and he had this Cougar.

“Isaid, ‘do you want to sell that?’ and he said, ‘oh, no.’ I said, ‘if you ever do, contact me.’ I gave him my card and by golly, two years later, he wanted to sell the car. We negotiated a price and I brought it home.”

It’s not hard to understand why the first owner was initially reluctant to sell or why Mance was interested enough to cross his fingers and make the offer; the XR-7 was the high-end Cougar and from the very first Mercury, Ford had seen the brand as its means to attract a clientele that was upscale, but not too upscale.

The first Mercury arrived in 1939 and at $916 to $1018, it somewhat bridged the gap between the costliest Ford priced at $920 and the cheapest Lincoln Zephyr at $1368.

That’s a Ford…Isn’t It?

The casual motorist might have taken a 1939 Mercury to be a 1939 Ford, but there was more of a difference than just details and trim between the two.

For the extra money that lifted him above the Ford, the Mercury buyer received a bigger and more powerful car; its 116-inch wheelbase was four inches longer and its 239-cubic-inch V-8—a flathead because, after all, it was a Ford product—produced 95 horsepower while the Ford’s 221 generated 90. It didn’t stand up quite as well against the 125- inch-wheelbase Zephyr’s 267-cubic-inch V-12, of course, asthat engine was good for 110 horsepower.

A serious Mercury restyling for 1941 after the lightly face-lifted 1940 model still bore a strong resemblance to the Ford and after yet another restyling for the war-shortened 1942 model year, the visual relationship between the cars continued. It would resume in 1946 before beginning to diverge three years later with the appearance of the first new postwar design, a car that looked much more like a Lincoln than a Ford. Those who missed the resemblance might also have missed the fact that the line of small type at the bottom of ads no longer read “Mercury Division of Ford Motor Company,” but “Lincoln-Mercury Division of Ford Motor Company.”

The 1949 Mercury went on to great things among hot rodders and customizers, but its transition from seemingly being a Ford behind a different grille continued with the new 1952 body. The Lincoln’s Influence was obvious and that body continued through 1954, when the division’s overhead-valve V-8 was introduced. Even the most loyal flathead fan had to admit that the OHV design really was better; it was exceedingly difficult to dispute the new engine’s superiority when its 256 cubic inches produced 161 horsepower while the older design offered 125 horsepower from 255.4 cubic inches, a difference in displacement of 0.6 cubic inches.

Sometimes, Though, the Difference Amounted to a Badge

Mercury began backing away from the Lincoln look in 1955, but in 1961, it combined a thinly disguised Ford body with a taillight section clearly inspired by 1958-60 Lincolns. Oddly Enough, the Lincoln connection was toned down for 1962, intensified with the 1963-64 models and then made more or less a constant component of the car’s character.

But while the full-size Mercury in most succeeding years managed to suggest a Lincoln without looking like a cheap version of one, holding the upscale-Ford image at bay elsewhere in the line was not as easy. The 1971 Comet was a 1971 Ford Maverick with different trim and the 1975 Mercury Monarch clearly was a Ford Granada.

Ford certainly wasn’t the only manufacturer to take that approach and go far beyond the sharing of basic components and platforms among models, and like its competitors, it ended up building virtually identical cars under multiple names. The Bobcat was a Pinto, the Topaz a Tempo, the Lynx an Escort, the Sable a Taurus and on and on. It didn’t necessarily make them bad, but in most cases, it proved counterproductive in the long run.

But This One’s Definitely Not a Mustang

A family resemblance, though, is another matter and while the feature car shows vague connections to both Ford and Lincoln, it’s a Mercury.

Right back to the Cougar’s 1967 introduction, the Mustang on which it was based had been deeply submerged rather than badge-engineered. In doing so, Ford had pulled off the neat trick of creating two comparable cars from the same platform; placing them in different areas of the same general market segment and having it work.

Once Ford introduced its Mustang to great success in 1964, a Mercury counterpart had seemed like a natural. When it finally happened, it was worth the wait.

The 1967 Cougar looked like nothing else thanks in large part to its hidden headlights and split grille that were mirrored in the taillight layout. Even the side view was different enough from that of a Mustang due to its smoother beltline and its lack of the Mustang’s cove, but there was a mild surprise under the hood where the base engine was a 200-horsepower 289.

The same V-8 was available in the Mustang, of course, but the base engine there was the trusty 120-horsepower, 200-cubic-inch six. The 320-horsepower 390 was available in either car and Mercury didn’t stop with the 390 when it came to the Cougar’s performance. Instead, it made sure that the requisite equipment ranging from a four-speed to dual exhausts to better suspension was all in the catalog.

It worked and although Cougars are sometimes—and unfairly—overlooked today, they were competitive early on in both NASCAR and Trans-Am events. They also benefited from Mercury’s application of the muscle car philosophy as the 427 and 428 became available in 1968 when the GTE appeared and the Eliminator followed in 1969 and 1970, when Mercury advertised that “spoilers hold it down. Nothing holds it back.” A 375-horsepower 429 was listed for the Eliminator in 1970.

The Cougar was completely restyled for 1971 and although its headlights were out in the open, the narrow center grille and vertical parking lights added up to a look related to Lincoln’s Continental Mark III. Like its front end, the Cougar’s rear was fresh and because it was somewhat bulkier, the overall effect was visually heavier even as the dimensions barely changed. The 429 was available for the last time, as the muscle era would soon begin to fade and Mercury would focus on the Cougar’s personal-luxury leanings. Eliminators and GTEs were gone, but the XR-7 with its slightly better trim and equipment was there as it had been since 1967. When it returned for 1972, its only engine was a 351 with 163 horsepower in base form and up to 266 horsepower optionally. Other performance cars were suffering similar fates.

A Pampered Cat All Its Life

The Mustang might have been the bigger seller among Ford’s pony cars, but if the Cougar’s fan base is smaller, it’s no less devoted. The feature car is proof of that, as Mance said that it looks about the same today as it did when he bought it on April 3, 1997, the result of the first owner’s having taken good care of it before finally relenting and selling.

1972 Cougar XR-7

GENERAL

Front-engine,rear-drive,convertible coupe

ENGINE

Type Overhead-valve V-8

Displacement 351cu.in.

Borexstroke 4in.x3.5in.

Compression ratio (:1) 8.6

Carburetor Two-barrel

Power 163hp@3800rpm

Torque 277lb.-ft.@2000rpm

DRIVETRAIN

Transmission Select-Shift automatic

SUSPENSION & BRAKES

Front Independent, coil springs

Rear Solid axle, leaf springs

Brakes(f/r) Power-assisted disc/drum

STEERING

Power-assisted recirculating ball

MEASUREMENTS

Wheelbase 112.1 in.

Length 196.1 in.

Track(f/r) 61.5/61 in.

Weight 3541 lb.

Tire Size E78x14

“He’d bought it brand-new,” Mance said, “but he did not have the original paperwork and that’s what I wanted very badly. He had a piece of paper with a bill of sale on it where he’d bought it from this Lincoln-Mercury dealer down in Westchester County (New York) where he worked. He paid $4700 for it. I drove it home… It drove great.”

The trip was less than 40 miles to Mance’s Kerhonkson, New York, home, but that probably would’ve been enough to provide at least an indication of any significant problems.

“As far as mechanical,” Mance said, “it was zero. I checked the brakes because it had 21,000 miles on it when I bought it and, you know, sometimes people don’t tell the truth. I wanted to make sure. It’s got power disc brakes in the front and they look like new. I pulled the drums in the back and they looked like new. All the paint markings are on the frame underneath from the factory. Everything was looking exactly as if it had never been molested or touched, so I kind of believe that that’s the original mileage. That 351 is kind of bulletproof (and) the transmission, I pulled the stick when I bought it and the fluid didn’t smell burned or misused, which I expected with him taking such good care of the car.

“And there was absolutely no rust. You cannot find a speck of rust except maybe on the driveshaft because it was raw metal or on the exhaust. There was no rust in the fuel tank area; that was still shiny.”

He did replace the exhaust, but purely because he wanted to go back to the original single from the duals that had been installed. Addressing minor cosmetic damage to the hood and trunk lid was the only bodywork necessary and he gave the air conditioning system a fresh charge of refrigerant, but some important components needed nothing.

“The top is all original,”Mance said. “The boot is original.”The glass rear window is original, too, and completely unmarked. The condition of the roof is further evidence of how careful the previous owner was with the car; if he put the top down or opened the rear window, Mance agreed, he did so properly.

It’s the same story with the interior.

“He must’ve taken good care of the leather,” Mance said, “because the leather’s just as soft as can be yet. I’ve always put saddle soap on it.”

The Cougar also has the four-way power seat and while that might seem quaint when compared to today’s seats that provide every conceivable movement for a driver of nearly any size or shape, he said that all of the adjustments function perfectly.

This Cat’s “Tail” Works

There’s another feature that’s farmore unusual than a power seat and that works perfectly, too, something Mance knows from watching the reactions among those in other cars.

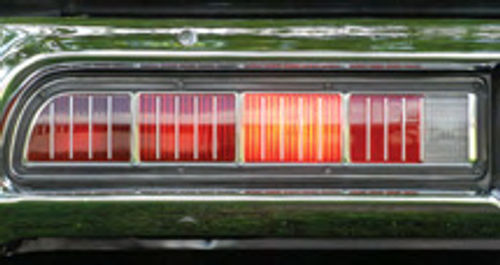

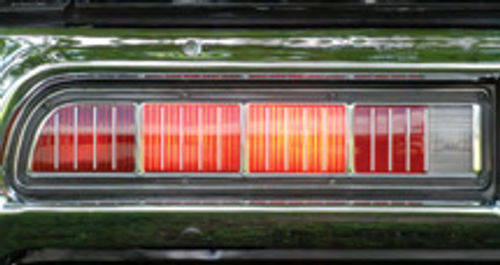

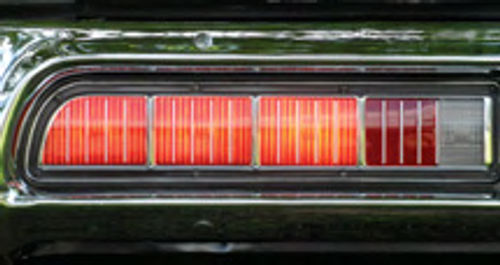

“The sequential lights always stand out to the driver behind me,” he said. “I see them pointing. I watch them in the mirror because I know from years ago when a friend of mine had a new Thunderbird. People used to follow his car to see the turn signals. I see them point. The driver, if he’s got a passenger, will point. ‘Look at that, look at that.’”

Some Things Interchange; Some Don’t

Obviously, the sequential signal requires more than a typical flasher, but Mance said a modern replacement is available.What’s less surprising, of course, is that Ford products are so strongly supported that nearly any mechanical part is quickly obtainable, so the chance of a Cougar like Mance’s being disabled for an extended period is slim.

Body panels might be another matter; being based on a Mustang Is not the same as being badge-engineered from a Mustang and that pretty much eliminates taking advantage of the Mustang’s popularity for an easy interchange. The Cougar panels are out there, though, even if the number of choices doesn’t match what’s available to a Mustang Restorer. But beyond sheet metal and mechanical components, there are some common parts. One of them—actually an assembly rather than a single part— could be very important.

“On the convertible top,” Mance said, “I know everything’s the same as it is on a Mustang.” He knows because he’s a long-time Ford guy whose other restored car is a 1973 Mustang completed before he bought the feature car. When he bought it, the Mustang wasn’t quite as nice as the Cougar.

“My Mustang I bought cheap,” Mance recalled. “I paid $1000. I thought I’d gotten the bargain of my life.”

The bargain turned out to be rusted badly enough to become a three-year project and while that convinced him that his next car should be one that didn’t need a restoration—hence,the XR-7—it also provided some insights into the fundamentally similar Cougar

“As far as problems,”Mancesaid,“the main one is rust,rust and more rust. Anything else can be easily overcome because of the availability of mechanical parts. Even some sheet metal you can find without too much trouble, so your biggest problem is going to be (structural) rust.

“We’re talking mainly about the torque boxes—cause it’s unibody—under the rockers, the rocker panels, quarter panels. The fenders didn’t rust too badly. The heel on the fender rusted, the quarter panel down behind the wheelhouse and up over the wheelhouse, (rust) ate right back in…

“If you get cowl rust or you get torque box rust, you’ve got to be well-equipped with lots of knowledge and time to fix them. That was the trouble with the ’65 and ’66 Mustang. The cowls rusted out where the heater vents went in. You had to have a chunk of old cowl if you were going to fix it right.”

Trim’s Not SoEasy

Although less important in the critical necessity sense than either mechanical or body parts, some of the trim might be easily replaced and some might present a challenge.

“They have reproduction upholstery,” Mance said. “The console is identical to a Mustang’s and the trim on it, the clock, the bezel, it’s Mustang.

“The interior parts are no problem because they’re reproducing them, but I think you’d have quite a job trying to find, for instance, the belt molding around the back of the convertible top. You might have problems finding the chrome trim around the edges of the doors. That side molding is original factory, that red strip down the side. It was an option for $20 or $30 from the factory, so I don’t know whether you’d find an exact duplicate on that, but it wasn’t an aftermarket part.”

All of that carries the assumption that it’s possible to find a carlike histhat, if not in comparable condition, is at least not terminally rusted, used up or hopelessly modified. Mance believes that it would be possible, but probably not easy.

“I think you’d have a hard time,” he observed. “You’d have to be California Bound—California or Arizona—’cause they were rust buckets in the Northeast. That’s why they’re gone.”

Maybe they’re not completely gone, but they’re unusual enough to stump those who see the feature car on the street.

“They’ll notice it,” Mance said, “and the biggest thing is ‘what kind of car is that?’ They take it for Lincolns, Buicks, Cadillacs, but the Cougar kind of faded from memory quickly, I guess. ‘That’s a Cougar?’ and then ‘oh, yeah, I remember Cougars.’

“There aren’t that many Cougar enthusiasts or Cougar people out there, but when you find one, he’ll come up and fall all over this car. I had several (at the Rhinebeck, New York, show) come up and fall all over this thing. ‘I had one as a kid.’ They know all about them. They know every inch of the Cougar, but the average person doesn’t know.”

Whether that changes and the Cougar suddenly becomes a must-have matters less than whether it’s appreciated in its current hype-free state.

As mentioned above, Mance had been looking for a car that needed no restoration, but he also wanted a convertible and was fortunate to come across one that met those requirements and had the plus of being a Ford product.

The Cougar XR-7 proved itself so right for him that, given the chance, he’d buy it again.

“Absolutely,”he said.“I’d Probably Buy it quicker…with what I know today.”