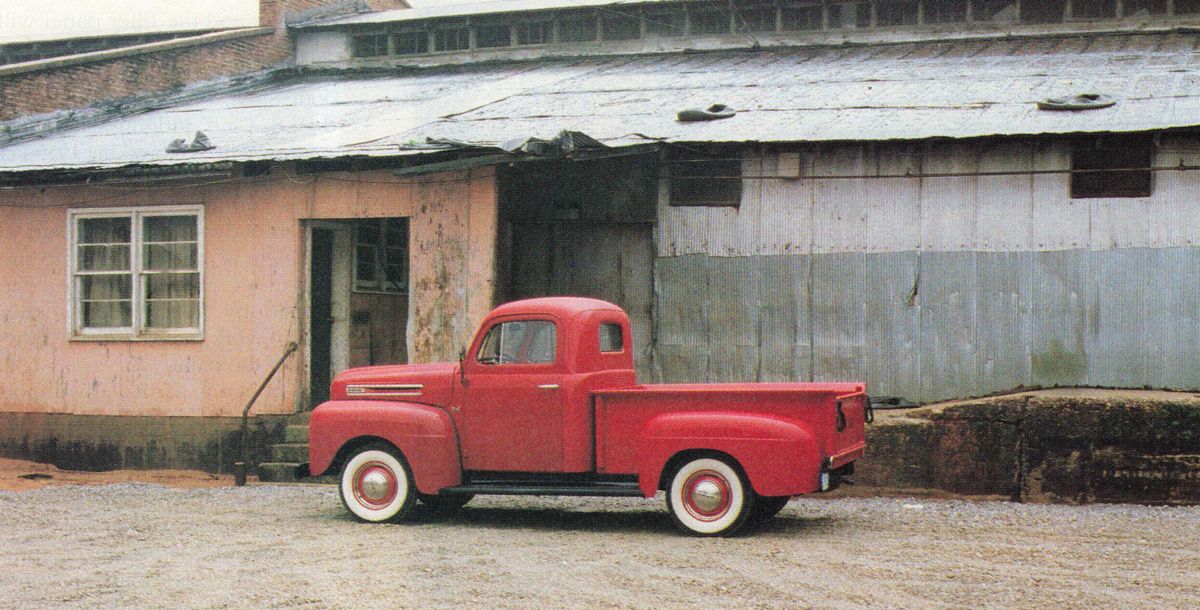

1949 Ford F-1 Pickup

Ford wasn’t ready in 1947 for Chevrolet’s Advanced Design trucks. Historian Jim Wagner, author of “Ford Trucks Since 1905” and a former Ford employee, recalls, “Chevy was beatin’ the shit out of us! That was the finest hour of the Chevy truck. I think Ford has as much interest with collectors today, but in those days ... the Chevys were much more popular.”

Things improved some in 1948 when Ford introduced its Bonus series. These were basically the same rugged trucks built before World War II, dressed up with new and nicer bodies.

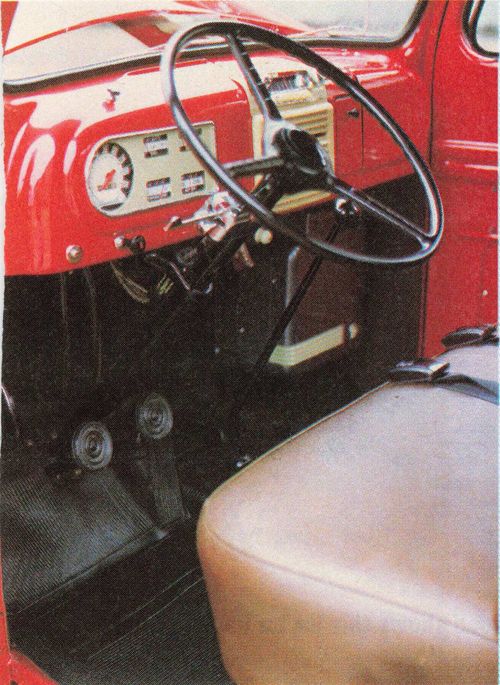

Modern fat-fendered styling was obvious. Ford also provided customers with bigger cabs and wider doors. They seem Spartan now, but with more standard and optional features like armrests, three-way ventilation, adjustable seats, dual wipers and sunvisors, the Bonus Builts were considered almost plush in their day

It’s no wonder Ford — sold 1,446,320 trucks between 1948 and 1952. The half-ton F-1 model was popular with farmers and small businesses while bigger versions (up to the three-ton F-8) tackled industrial chores. The °53-56 F-100 is more popular with collectors today, but the simple, stylish Bonus Built makes an excellent restoration project.

Holey Terror

Rust, the first thing to look for when evaluating a restoration candidate, is especially unpredictable on old pickup trucks. Mike Chesser, owner of Chesser’s Auto Emporium, is a specialist in restoring Ford cars and trucks from the flathead era. He warns that rust can appear anywhere on a pickup: “You never know when somebody left a bag of fertilizer lying somewhere and it ate a hole.”

Some places are more prone to rust than others. On F-1 Bonus Builts, Chesser suggests that the seam, which wraps from the headlights around the side of the front fenders, tends to collect dirt and is a vulnerable area. An internal brace behind the fender also catches dirt and salt and eventually dissolves. The bottom rear corners of the cab are the next most likely spot, and less often rust occurs at the bottom of the doors.

The hood also requires inspection. Heavy trim and latch hardware frequently caused the sheetmetal to crack near the front, and years of use as a table or sawhorse often left dents. Cracks can be repaired by welding, but Chesser warns it takes some real talent to repair a dented hood. He prefers to find an undamaged hood to start with.

Bit by the Bed Bug

Few old pickups have nice beds, and the wood can look particularly nasty after decades of rain, sun and abuse. However, it’s not too hard to cut new wood (most people use oak because it holds up well). The condition of the metal is much more important. Chesser says “the seams in the bed, the corners and the filler panel will rot. They make the difference between saving and replacing the bed.”

Doug Shull, a member of the Early Ford V-8 Club judging standards committee, who restored his 1950 F-1 in 1983, warns that “trying to straighten a box and make it look like anything is bloody slow going.” Part of the problem is the bed walls are single thickness, so there’s no place to hide a sloppy weld or dent repair. The metal work must be nearly flawless under the paint.

A good bed is particularly important on 1948 and 1949 Fords. These trucks used a bed design dating back to 1938. These originally had a metal panel with stamped ridges covering the wood floor. This is almost never found intact and is tough to reproduce, so Shull says many restored trucks leave the wood floor uncovered. He adds, “the early boxes had embossed sides, the stake pockets curved at the bottom, and different fenders were used with a notch at the back to get around the embossing.”

Sometime during the 1949-50 model run, Ford switched to a new, cheaper design with flat sides, different fenders and a bare wooden floor. These later beds are more commonly reproduced and relatively inexpensive. In contrast, Chesser says the early beds are hard to find and “real expensive — you can spend $2000 pretty quick.”

Mistaking Identities

The beds were only one running change between 1949 and 1950. Even experts have trouble telling these two years apart. According to historian Wagner, Ford never made a clear break. Different running board mounts were introduced, series trim on the cowl switched from die-cast to stainless steel, and column shift replaced floor shift, but all these changes were made gradually. Another problem was that dealers in those early days frequently retitled leftover models to sell as new trucks the next year. The identification plate and engine number are the only sure ways to determine a truck’s date of build. Shull’s pickup, for instance, was titled as a 50 but probably was built in late ’49. It incorporates some, but not all, of the running changes made between the two years. Improvements for 51 were much more dramatic. The recessed grille of previous years was replaced by a gaping mouth filled with a massive horizontal bar, capped by the head light pods and trisected by three bulging teeth. The optional Five Star Extra Cab provided more styling touches, including two-tone upholstery and door panels. Shuffled hood trim helped distinguish the 1952 model, the last of the Bonus Built Ford trucks. Also in ’52, a new overhead-valve six-cylinder engine replaced the flathead six and the V-8 engine was pumped up to 106 horsepower.

The Smoking Gun

Although six-cylinder engines were available in Ford trucks, collectors should look for the famous flathead V-8. This is one of the most popular engines ever made, so parts are readily available to rebuild even the most tired example. For the adventuresome, simple bolt-on performance modifications such as hotter cams, Mercury cranks and multi-carb intake manifolds can take the motor way beyond its original 100 horsepower. Mileage is not an important indicator of the mechanical condition of an F-1, says Chesser. It depends more on how the vehicle was used. Low-mileage examples may have spent their entire life lurching around construction sites in first gear with a heavy load of bricks, while a few high-mileage trucks rolled up the odometer carrying the occasional hay bale or bag of grass seed.

Thus, blowby is the best tell-tale of a ragged-out engine. Chesser recommends removing the breather cap from the oil filler neck while the engine is running: “If it sits there with the cap off and puffs, it’s got a lot of wear on it (and is due for a major rebuild).”

Ford V-8s had a reputation for overheating and vapor-lock problems, but Shull says this has more to do with lazy mechanics and restorers: “You know damn well the American public wouldn’t have put up with this stuff when they were new.”

Because the exhaust ports pass through the water jacket to reach the manifold, it’s important to keep the cooling system in top-notch condition. Shull believes, “the reason everyone is bitching is because they didn’t clean the block thoroughly when they rebuilt it, and there’s a lot of rust and scale in there. You can’t just put them in the caustic soda tank and get all the rust and sludge out. Get in there and dig around and you'll even still find some core sand left.”

Shull also suggests inspecting the radiator core to make sure the fins are still soldered firmly to the tubes. If they’re loose, they won't help radiate heat. He also says it’s important to have a thermostat installed in the system. This slows down the circulation of water and gives it more opportunity to absorb heat from the block.

Vapor lock is usually the result of a poor fuel pump or slight air leaks in the fuel lines, Shull says. “The pump has to suck the fuel out of the tank behind the seat and raise it about 24 inches. If the pump and lines are 100 percent you’re not go ing to have this so-called vapor lock. Most of what you hear about is untuned cars or guys that don’t know how to fix things.”

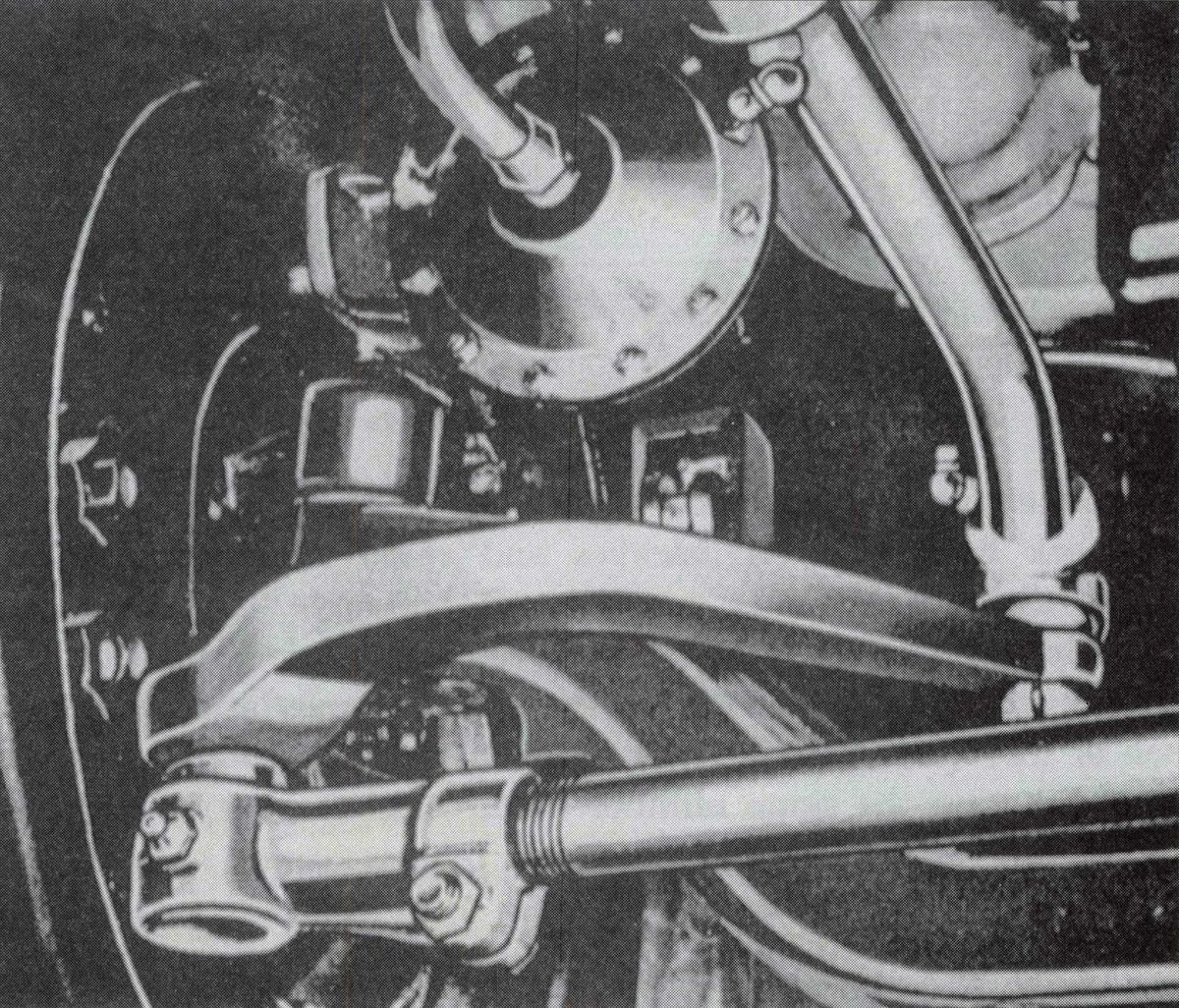

Steered Wrong

The steering box was a weak point on Bonus Built trucks. They were built at that time with bushings instead of bearings and had to be greased periodically, a maintenance step that often was overlooked.

Therefore, it’s not unusual to find the adjustment nut run all the way in due to premature wear. That means the next time the steering gets sloppy the box will have to be rebuilt or replaced. Shull says the steering gets notchy as the gears deteriorate.

Parts are available to repair the steering, but they ain’t cheap. The worm gear alone costs $114, and the sector shaft goes for $185 in the Concours Parts and Accessories catalog. Installing the new pieces requires special care, Shull warns. The tube that comes down from the steering wheel is mild steel, and it is easy to bend or kink it trying to press on the new gear.

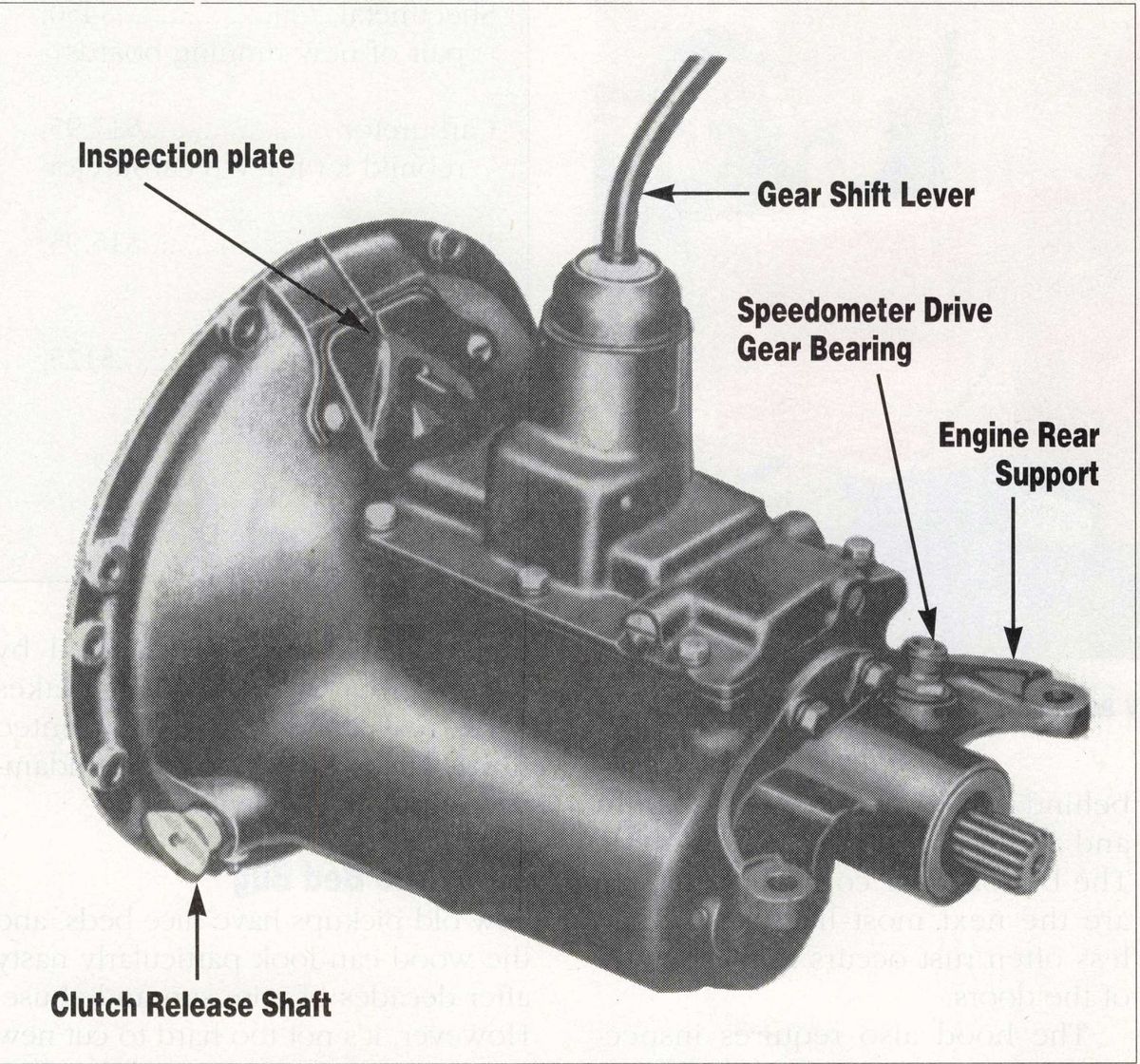

Other parts of the drivetrain and chassis are tough and foolproof. Ghesser «says novice restorers shouldn’t be afraid of the Bonus Built Fords: “They’re still a simple enough truck that someone with basic abilities can take it apart and do stuff without running into something too hard.”

Turning F-1 into A-1

The early Bonus Built has an appealing style and its simplicity is an advantage for first-time restorers. And with most parts readily available, you don’t have to worry about getting bogged down for months waiting for the UPS-man to deliver a rare whatzit. So what does it cost to get into a project like this?

Price guides start the ’48-50 pickup trucks (with a V-8) at under $1000 for a barely salvageable project. Given the scarcity of good sheetmetal, it’s worth the extra money to start with a well-running, presentable vehicle in original condition or an older (but decent) restoration. Prices will generally fall between $3500 and $4000 for a truck in what is considered to be number three condition. Top examples sell for $10,000 or more, leaving plenty of headroom for careful restorers who don’t want to outspend the value of their truck.

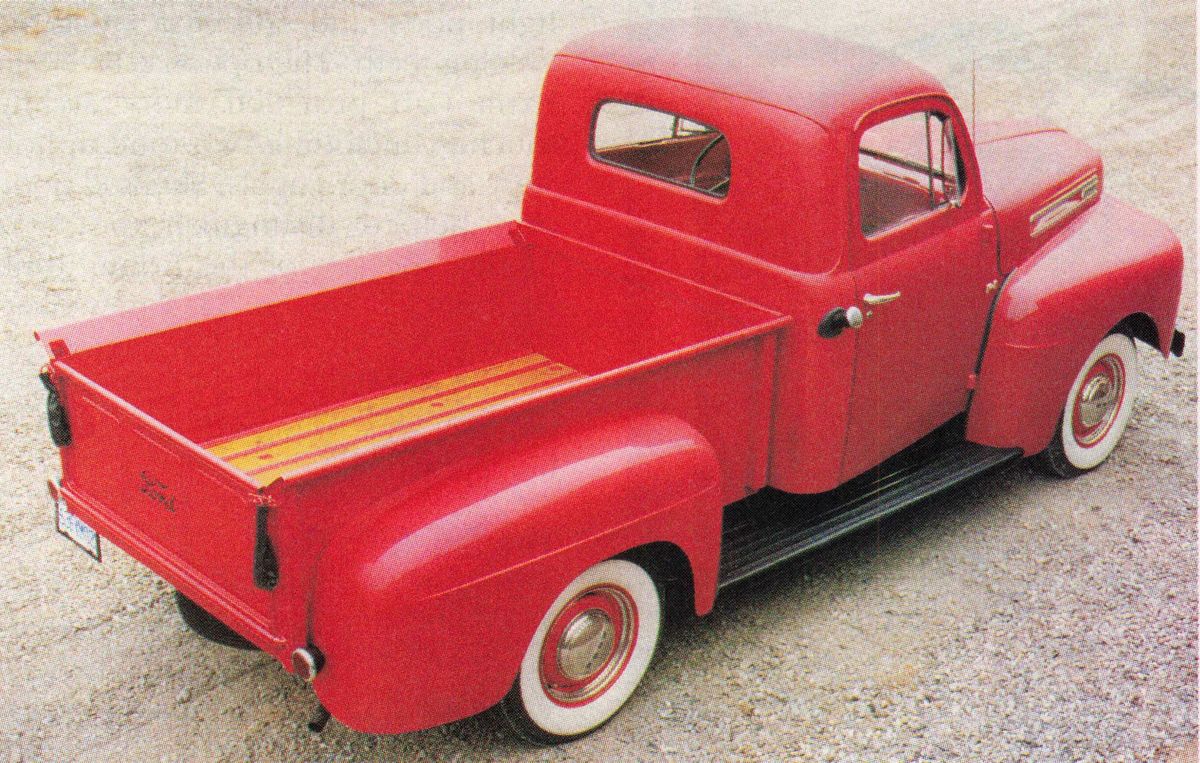

Shull doesn’t like the tendency to over-restore old trucks. He says farmers were notorious cheapskates in the old days. Sometimes they wouldn’t even order heaters, preferring to rob one out of a junk sedan and install it themselves. He never saw a truck that sold new with wide whitewalls.

Yet most restorers like to dress their trucks up with all the options: whitewall tires, radios, dual taillights, the works. Perhaps because the basic trucks were so ashes-and-soot plain, these extra touches make for a Cinderella-style transformation. Drive a flashy F-1 Bonus Built to a car show today, and you'll be the belle of the ball.

To be picky

AIthough beautifully restored, this truck has some incorrect details that wouldn’t pass muster at an Early Ford V-8 club meeting. Anyone interested in restoring a Ford pickup to strictly authentic original condition is encouraged to contact the Early Ford V-8 club and speak with an expert.

1. Recessed grille panel, including headlight surrounds, should be painted argent aluminum (silver) on ’49-50 trucks. Stainless steel trim was optional. Ford would paint fleet trucks in any color combination the buyers wanted, but it’s doubtful that the grille assembly would have ever been painted body color.

2. Green engine is wrong color, should be red.

3. Bed is the straight-sided variety introduced late in model run. It may be correct for this truck, depending on build date and the expert you talk to. 4. Bed is painted incorrectly, though this is a common mistake. Originally, beds were assembled and then painted, so wood and metal dividers in floor would be same color as sides. Most restorers choose to finish the wood naturally as on our feature truck.

5. Few trucks included all the options on this vehicle: heater, radio, dual wipers, dual taillights, stainless grille trim, whitewall tires, chrome wheel trim rings, seat belts, turn signals, etc. These are OK with the Ford club only if they are original accessories and installed correctly.

Fountain of Youth Ford

Hayse Boyd, owner of our featured truck, is a retired Alabama physician with thinning hair and a methodical drawl. But the way he acts around his truck, he might as well be an excitable 16-year-old. Dr. Boyd purchased the 1949 Ford in restored condition from a Georgia collector. Though Boyd's collection includes some flawless early Thunderbirds and a pristine Lincoln Continental convertible, he particularly loves driving the truck and has put 3000 miles on it in the past three years.

“It’s just a pleasure to drive,” Boyd says. “We go to church in it some, and | get it out on pretty days and ride around some. It’s got plenty of power and runs right along with traffic.”

Indeed, during our photo shoot the antique Ford happily trundies down the highway at 55 mph. There are no elderly-sounding groans or creaks from the chassis, and the old V-8 does its job with youthful vigor. Ford flatheads had a reputation for running hot, but Boyd says proudly,

“this one is not temperamental, it cranks easily, it runs great, it doesn't overheat, and there’s very little dripping oil under it.” Riding in this time machine is a vintage experience. Hurrying the spindly gearshift yields a boxful of crunches; patience pays off with smoothly synchronized cog-swapping. The huge 18-in. diameter steering wheel requires constant minor adjustments because of the solid front axle’s archaic handling characteristics. The old Ford rides with a bouncy gait ideal for ambling across a pasture.

The instruments are easily legible in their art deco arrangement. With the rubber floormats and vast expanses of shiny red paint, the cabin has a Tonka toy atmosphere. Boyd's pickup is luxuriously equipped with a heater and a massive jukebox of a radio. | wouldn't be surprised to punch a memory button and hear the Andrews Sisters come harmonizing out of the warm fog of static.