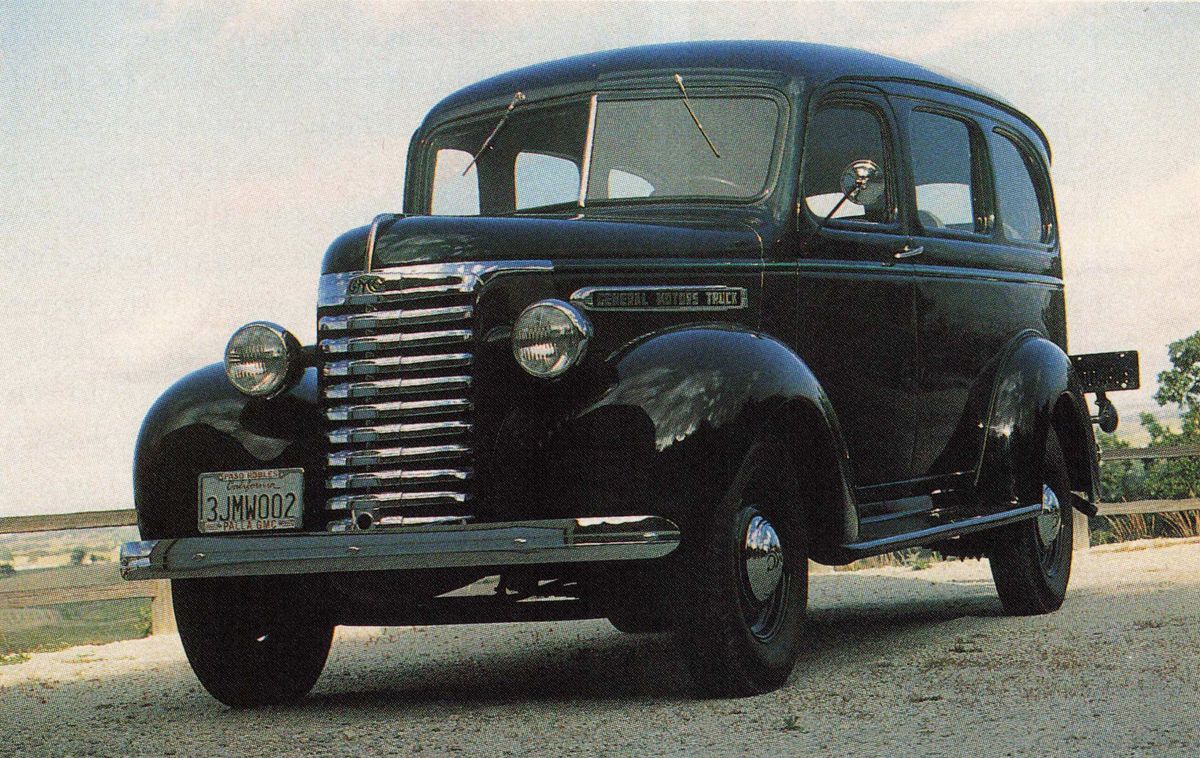

1939 GMC Suburban

Works like a truck, but knows how to play hard too. Sixty years ago General Motors came up with a cool idea that demonstrated how your average, hard-working panel delivery truck could deliver you, your family and friends to the great outdoors. Should you be surprised that the modern suburban utility vehicle was popular then for all the same reasons it is popular today?

It’s always feels good when you successfully mix business and pleasure. In the vehicular world this is epitomized by the champions of utilitarian transportation. In the mid 1930s versatility was appreciated maybe even more than today. The GMC Suburban was on hand to blaze this frontier trail. And you thought this concept was only developed during the latest minivan/sport utility vehicle craze.

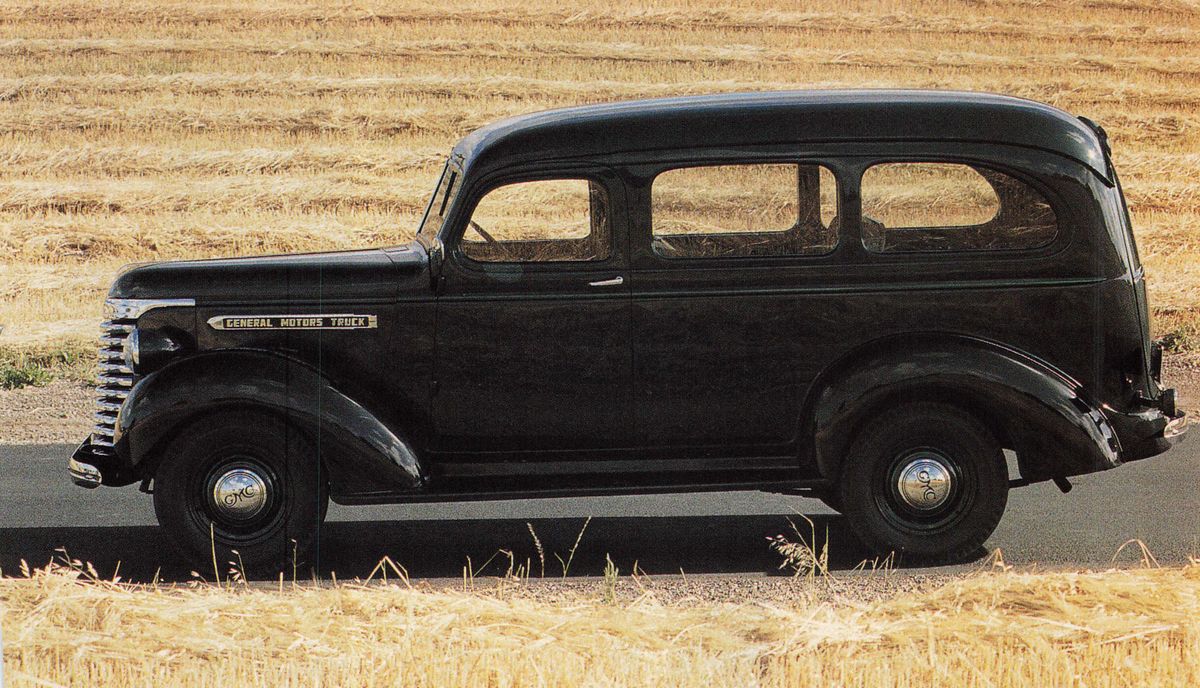

The Suburban, first introduced by Chevrolet as a 1935 model in the fall of 1934, was an idea whose time had come. The GMC Suburban followed one year later. Based on the panel delivery truck that was already being produced at that time, the idea to add windows and additional seats was perhaps a flash of brilliance, but more accurately a stroke of common sense. At a time when people were anxious for adventure and the great natural wonders of the American wilderness were being discovered by increasing numbers, a hybrid vehicle that combined the ruggedness of a light pickup truck with the passenger hauling capability of a small bus was a natural progression.

There were similar vehicles at that time. The station wagons were wood-bodied and more car-like. Specialty vehicles produced by Fargo and Checker were also referred to as suburbans, but they lacked the all-steel construction and general toughness of the General Motors products. They also lacked the dealer network that could put their products in front of as many potential customers.

At this time, GM trucks were actually being built by Yellow Truck and Coach Manufacturing Co. in Pontiac, Michigan. The Chevrolet and GMC versions were nearly identical. However, the GMCs carried slightly heavier frames and more powerful engines. On the job they were generally considered to be a beefier truck.

Good Timing

Eight years ago, when John Palla saw a Classified ad for a 1939 GMC Suburban, he thought it sounded like the kind of restoration project that he could really enjoy. He was recently retired from owning an agricultural supply business in Paso Robles, California, and was anxious to begin his first restoration project.

During his 39 years in business, Palla had sold hay balers, combines, tractors, and among the other farm-related supplies, GMC trucks. When Palla read the ad, his interest was aroused. It was a good match. The connection may have been based on the fact that both the Suburban and Palla have an innate, almost infinite, ability to be resourceful.

Like most who begin their first restoration project, Palla began with a limited amount of information from which to illuminate his path. In these cases, the ability to improvise is a handy tool.

Upon first inspection, Palla found the truck to be in pretty good shape. The fenders, bumpers, and running boards had been removed and were loaded inside the vehicle. It wasn’t until after he bought it that he actually unloaded everything and took inventory of what he had. All the body panels and parts seemed to be there.

Although the cab was of all-steel construction, behind the cab the floor was made of wood. It had deteriorated over the years and needed to be replaced. Replacing the floor, Palla discovered, meant that the body would need to be removed from the chassis. This led to the truck being stripped to its pressed-steel frame, sand blasted and repainted.

Rust hadn’t destroyed any of the body or frame, but mechanically it disabled many components to the extent where replacement was the only alternative. After many years of storage in a shed, rust had invaded and established a foothold on every metallic surface.

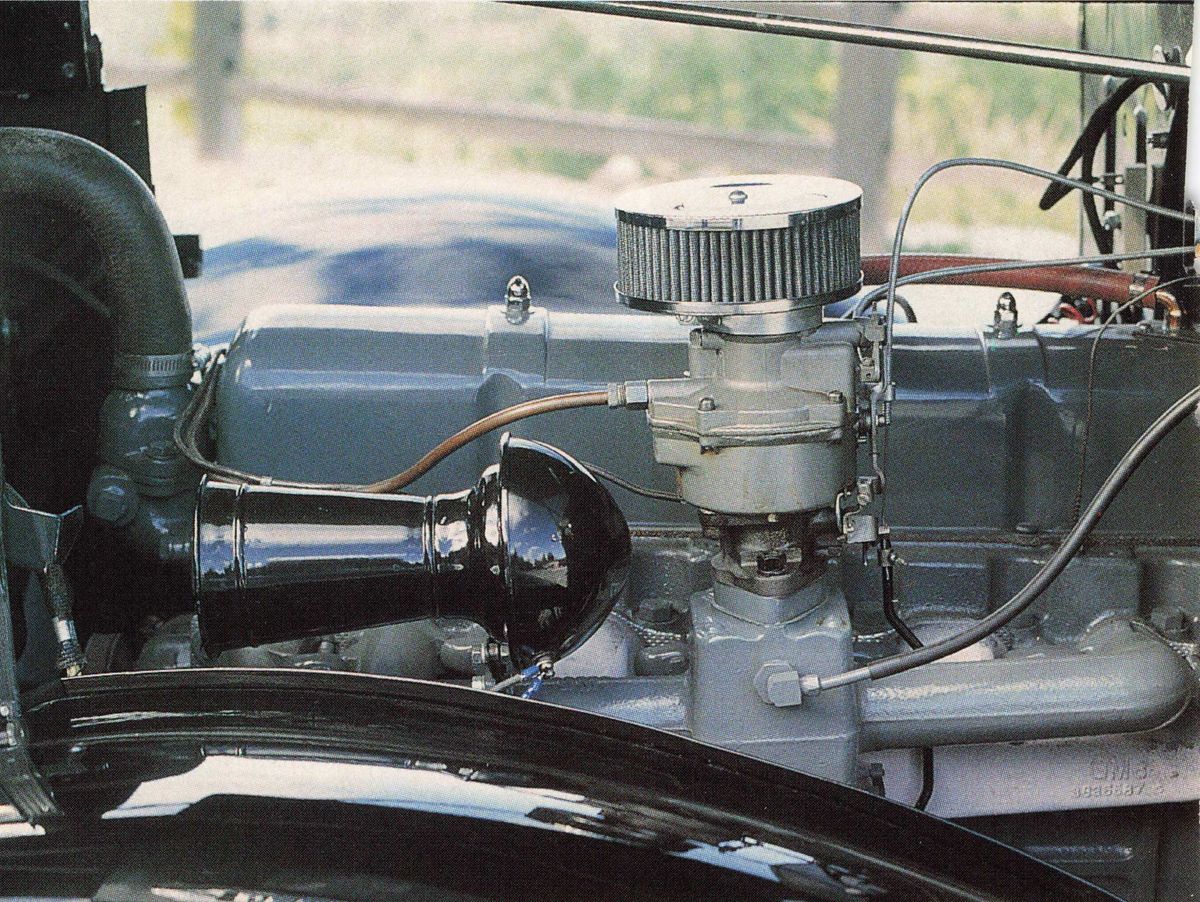

As a backup source of spare mechanical parts, Palla purchased an engine and chassis from a 1946 Chevrolet panel delivery truck. Even though Chevy and GMC did not share engines and chassis until the late 1950s, many of the components were similar. Improvisation on Palla’s part would narrow the gap in several instances.

The original 1939 GMC 228-cubicinch, valve-in-head engine was removed and replaced with a rebuilt 235-cubic-inch Chevrolet six. It bolted into the engine compartment with no alterations necessary. To maintain the GMC appearance, Palla cut off the top portion of both the Chevy and GMC valve covers and then welded the GMC-identified pieces onto the Chevy valve covers. Unless you.are well-versed in the differences between these engines, you would not realize the swap had been made.

Learning It by Doing It

Further improvisation became necessary. when rebuildins the Hotchkiss-drive rear end. Palla was stalled while trying to locate carrier bearings and pinion bearings. Finally he decided to implant a late1940s rear end with the same 4.11 to 1 gear ratio as his original. In order to mate the original three-speed synchromesh tranny and keep the spline from the original propeller shaft, he cut the original shaft and welded it (a local machine shop lined up the two shafts and balanced the final product) to the one that matched his replacement rear end. In the case of Palla’s truck, the propeller shaft is tubular and enclosed in a torque tube. The universal joints are needle bearing type and oil lubricated.

By this time he had learned that finding parts for a 1939 GMC Suburban can be challenging. Going into the project Palla didn’t know anyone in the old car hobby, but through some investigative work he was able to build a network of sources. His most useful source for parts and supplies was The Filling Station, a mail order parts source based in Oregon.

Ongoing Adventure

The semi-elliptic, alloy-steel springs were disassembled and restored. The original single-action shock absorbers were rebuilt and reinstalled. As work on the chassis continued, Palla purchased and installed new brake shoes, brake lines, brake cylinders, and a master cylinder. The system on this truck is hydraulic, two-shoe, internal expanding on all four wheels. To his surprise these components were easily located and ordered.

After the wheel bearings were replaced, the new 6.00x16 tires were mounted on the freshly painted rims and they replaced the saw horses that had previously held up the chassis.

The original steering box, which worked on a roller-bearing, worm-type system, was replaced by the more modern ball-bearing type that was available on the panel delivery chassis that Palla had in reserve. In an improvisational fashion much like the drive shaft fix, the steering shaft from the replacement steering box was mated to the original steering shaft that connected to the steering wheel.

Repairing the rotted old flooring was one of Palla’s biggest chal lenges. It was constructed of 4-inch plywood, so he began the repair with a 4-foot-by-8-foot piece of 4inch exterior-grade plywood. This provided the necessary length, but an area six inches wide by two feet long in front of and in back of each wheel well still required attention. Palla took care of this detail by creating a tongue and groove joint in the sides of the plywood and gluing the four pieces in place.

Using the old floor as a pattern (This wasn’t easy given the condition of the previous flooring.), Palla was able to pre-drill the holes that would accommodate the mounting bolts. In order to install the two rear seats properly, the floor had to be cut so eight steel mounting pockets could be installed. Each plate had to be recessed into the flooring and additional routing was required to allow for the extra depth of the %-inch carriage bolts that secure the seats.

Insider Information

Inside the cab, the side panels and door panels and any moldings were removed and repainted. All the exposed metal surfaces inside the cab were sanded and wire brushed be fore a coating of rust-inhibiting paint was applied.

The dash was removed and all the gauges were disassembled. The bezels around the face of the gauges were rechromed and new decals were applied to the gauges. The speedometer, ammeter, oil pressure instruments include-a gauge, electric gas gauge, and water temperature indicator.

All the window glass was also replaced with glass that was purchased from a local supplier. New weather-stripping and window channels were installed. All the window regulators were disassembled, cleaned and lubricated. The windshield wiper motors were disassembled and cleaned. A new wiring loom was installed under the dash and out to the engine. All wiring was replaced and the electrical system was converted to 12 volts.

Suburbans were available with two types of rear entry. Palla’s model has the tailgate/liftgate option, but vertical hinged doors were also offered. According to Palla, the rear tailgate door frame on his vehicle was in poor shape and a new frame was painstakingly fabricated to fit the contour of the body.

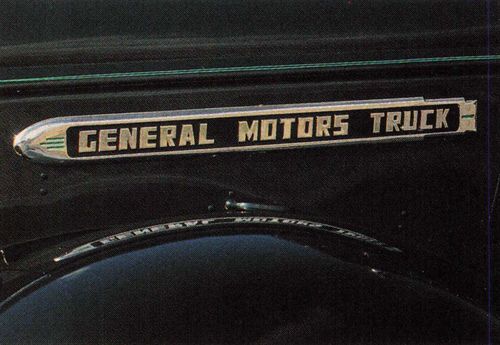

On the Grille

The front grille could not be rechromed in one piece so it was deconstructed into 18 small pieces. This was accomplished by drilling out the spot welds and grinding off the residue: In the: process: three pieces were destroyed. Replacements were fabricated by using surviving pieces as patterns and then making slight alterations as necessary. When the 18 pieces were sent out to be chromed, only 17 were returned. With a saber saw and a hammer, Palla fabricated a replacement piece from a four-inch piece of exhaust pipe he picked up in a muffler shop. Now that the 18 pieces are spot-welded into one piece again, it is almost impossible to tell which piece used to be a muffler.

From the fateful day Palla brought home the Suburban to the first day he drove it through town after finishing his restoration, slightly more than three years: had slipped by. Palla says this is probably his first and last restoration project, but he never gets tired of telling the story how this vehicle was brought back to life.

Down at the Taste of Paso Restaurant where Palla likes to go for breakfast, people still come in and ask about the “old truck” in the parking lot. If you have time for a cup of coffee on almost any Saturday morning in Paso Robles, John will repeat the story. It might be called “A Suburban Adventure.”