FINDING AND FIXING ENGINE OIL LEAKS

The Start of Your Search

If your collector car is using too much oil, it might be losing it from an opening that isn’t sealed well or it may be burning it off. Start tracking down the type of problem you have by looking on the ground under the car. If you see a gooey residue on the floor, you have an oil leak. If you see blue smoke coming from the tailpipe, the car is “burning oil.” The latter could be caused by worn rings or you might have a defective vacuum pump or oil pump or a gasket or seal that isn’t doing its job for one reason or another.

Your last parts order probably came in a box lined with plain craft paper that was crinkled up to protect the parts. Flatten out a piece of paper large enough to fit on the ground under your engine. Be very careful that the paper won’t wind up touching hot parts. Spread it out under the car and run the engine at a speed higher than the normal idling speed. After 5 or 10 minutes, shut the car off and check the craft paper for oil spots.

Chances are the spots are not directly below the actual leak spot. Oil tends to travel from the leak spot along a flange or chassis member until it finds an open section, at which point gravity will pull it to the ground. Oil will flow even farther from the leak spot if it is hot or if it is being pushed in a certain direction by a rotating cooling fan. Often, you can pinpoint the actual leak spot by looking for “oil washed” areas on the engine.

Some typical leak spots are the front timing case cover gasket, the valve cover (or valve covers on a V-type engine) gasket(s), the oil pan gasket, the crankcase seal at the front and/or rear of the oil pan, the oil pan drain plug gasket, side cover gasket, oil line connections on an L-head engine, oil filter connections, external oil pump gaskets, etc.

It’s Not Always a Major Task

Sometimes it is possible to fix an oil leak quite easily. It might be a matter of simply tightening up oil pan bolts, replacing some easy-to-change gaskets (such as a valve cover gasket) or even just tightening up the oil drain plug. We had a 1952 MG TD that was leaking a steady stream of oil from the front timing cover. After filling the oil pan, the car was driven 30 miles to a machine shop that simply drilled a slightly larger hole, threaded it and put an SAE bolt in the hole. That took care of a pretty good leak for around $50.

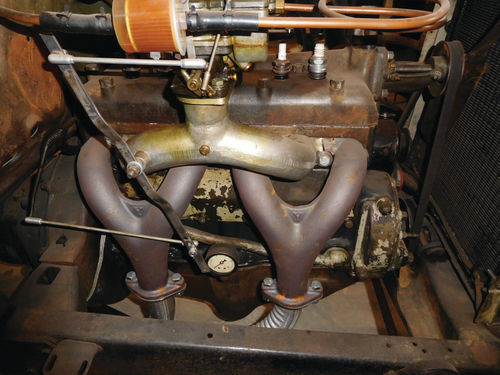

A different type of hole allowed oil to leak from the Yellowstone Trail Oakland. Prior to the start of the trip, we had taken the oil pan off the car in order to shim the rod bearings. It was greasy but seemed to be in good shape. We did not know it was missing a piece (an oil level sight gauge used only on early 1917 models). We manually cleaned the pan and made new gaskets and end seals.

On the first day of the trip, an insert bearing disintegrated and we had to take off the pan again. This time we had it sandblasted and it turned out to be rustier than we thought. The media created a small hole in the pan.

The hole was so small that we didn’t see it, but as soon as we put oil in the pan, it started running out the bottom. Being on the road, we did not want to take the pan off again; we had to get going. So we used a screw inserted in the hole and J.B. Weld to fill it and the repair worked fine. In fact, we have not yet removed the pan to braze it.

A Valve cover May Be the Culprit

Locating oil leaks can be difficult. Let’s start near the top of an overhead valve engine with a valve cover leak. If your valve cover gasket is not sealing well the cover may be oily or you may smell an odor from oil hitting hot exhaust manifolds. Leaking oil can creep down the side of an engine and seem to be from elsewhere.

An inspection mirror helps to locate hidden leaks. Start at the top and follow the flow. A valve cover can leak oil when the car is running, but not while it’s sitting. Gasket replacement is simple but varies by engine. The hard part on newer cars can be getting to the valve cover itself.

Start by tightening the hardware that holds the valve cover on the engine. This is usually a bolts-and-washers fix, but wing nuts and other fasteners are used on some old cars. The fasteners can be around the edge of the cover or down through the centerline. If your shop manual has specs, tighten the bolts with a torque wrench. Over-tightening them can make the leak worse and can damage the valve cover by cracking or bending the metal.

Do a test run. If there’s still a leak, let the engine cool off and start figuring out what you have to remove to take the valve cover off. Linkages, spark plug looms, various hoses and other parts may need to be dealt with. Once you have access to the valve cover, you may have to tap it with a rubber mallet to break any remaining seal. Lift off the valve cover, being careful not to drop small parts into the valve train.

If the valve cover has a flange around the edge, place it on a flat surface and make sure the flange is flat. If it has waves in it, use a small, light hammer to flatten it better. Remove the old gasket and install the new one. The old gasket may be stuck in a groove and need to be carefully dug out. Use plastic scrapers on aluminum valve covers or cylinder heads. Use new grommets on valve cover bolts. Use silicone or sealers only if your shop manual or gasket instructions recommend it. Follow instructions on the sealing product. Install the valve cover with the new gasket in place and torque the bolts. Then install all the parts that you had to remove to take the valve cover off the engine.

Flatheads Are Different

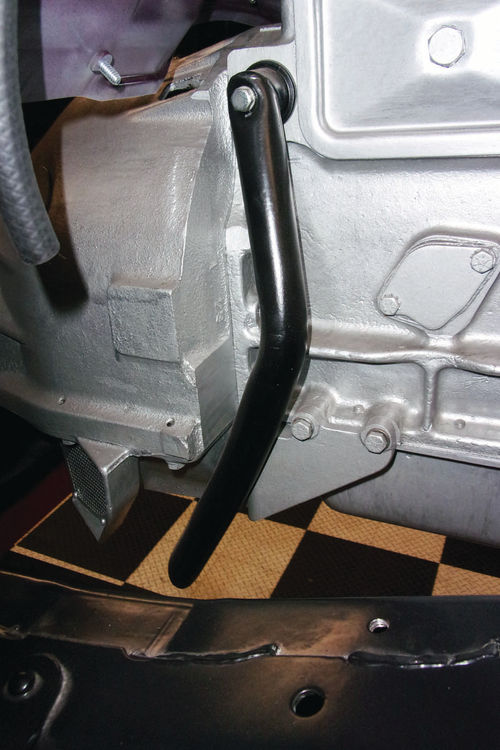

The flathead engines used in many older vehicles (mostly pre-1960 models) do not have valve covers and gaskets. These types of engines have the valves in the block and valve adjustments are done from the side of the block. They will have front and rear side covers for each of the valve galleries and these were covered with plates (usually called side covers) that functioned similar to valve covers but are flatter in shape. The side covers each have a gasket that can leak. The side covers are held on by bolts that thread into the block. Gasket replacement is similar to valve cover gasket replacement but holding the gasket in place can be harder. You may want to use a sealer to help.

Consider the Oil pan and Road Draft Tube

The flanges on the edge of an oil pan can also take a real beating over the years. If they get “wavy” it will be harder to effect a good seal. If the oil pan seems to be leaking around the edges and it can be easily removed without taking half the suspension apart, you may want to consider doing this. Once it is off, place it upside down on a flat surface and use a small hammer to flatten the flange.

If the oil pan has a cork gasket, you may want to see if you can get a gasket made of materials like neoprene or durometer rubber. These are available for more popular engines like the Chevrolet small-block V-8.

Before PCV valves, engines had road draft tubes (crankcase ventilators) that directed blow-by out of the crankcase. Too much pressure in the crankcase can create external oil leaks that will show up as oilwashed areas of the pan on the same side as the road draft tube. Often this indicates the need for new piston rings or a complete engine overhaul. However, a clogged road draft tube outlet or a clogged inlet at the air cleaner can cause too much crankcase pressure. This is easy to fix by removing the tube and cleaning it out. A bent tube can also create a vacuum that sucks crankcase oil out.

When a PCV Goes Bad

A bad PCV valve may be the cause of an oil leak, as well as excessive oil consumption. Oil will leak through the seals and drip onto the ground. Increased pressure in the crankcase after the PCV valve fails causes these conditions. The oil is forced out of the crankcase through seals and gaskets since there’s no other way to relieve the pressure. The leak will cause the engine to burn oil and lead to a puddle of oil under your car. Installing a new PCV valve should solve the problem and eliminate any leakage.

In addition to oil leaking from your engine’s oil pan gasket, leaks can develop at other gaskets such as the one used to seal an external oil pump against the engine block. This is a rather small gasket, but as discussed earlier, even a small hole in the oil pan led to a steady stream of oil flowing out of the Oakland’s oil pan.

Consider the Fuel Pump

Some cars have only a fuel pump and some have a combined fuel and vacuum pump that bolts to the block and has a small gasket. If the diaphragm in the pump ruptures, the vacuum may increase pressure in the crankcase and force oil past the cork gasket, resulting in a leak.

Check Out the Oil pan Plug

Another potential location for a leak is the oil pan plug and its gasket. It is not uncommon to see an oil pan that is dented from some type of impact at the spot where the drain plug is located. The threads on drain plugs can also get stripped, making it impossible to screw the plug tightly into the pan. Allrubber plugs that push into the hole used to be available from aftermarket parts suppliers to replace metal plugs with stripped threads. We recommend sticking with a screwed-in metal plug. Drain plugs usually have a wavy metal gasket that squishes when the drain plug is tightened. Plugs with no gasket probably won’t work as well and will possibly leak.

Metal Lines and Fittings

Metal lines for engine oil can also develop leaks, as can the fittings used to connect oil lines to each other. In rare cases, the lines could have a hole worn in them, break or be damaged by an accidental occurrence, but most leaks from oil lines will be due to loose fittings that usually can be tightened up to stop the leak. It’s also possible to find lines that leak because the fittings have been accidentally cross-threaded. In this case, the fittings themselves will have to be replaced.

Leak Sealers

One potential way to fight oil leaks in old cars is to use additives that are supposed to make seals and gaskets swell up so they don’t leave gaps for leaks to pass through. New Tech’s No. 4008 Seal Lube is such a product. New Tech calls it a Seal Expander and claims that it stops rubber seal problems that allow crankcase seals to leak engine oil. We have not tested Seal Lube or any similar products but be aware that they are out there. (Editor’s note: Have any readers had experience, good or bad, with these types of sealing products?)

Modern Possibilities

With some older engines, you can upgrade from original equipment parts to higher-performance parts that are designed to prevent the chance of an oil leak. The best example involves parts designed for Chevy small-block V-8s, an engine family with many available racing and performance parts. The upgraded parts may or may not change the original looks of your engine, but they should fit well and help fight oil leaks.

Take the aftermarket JM1015 Six Valve Mechanical Fuel pump marketed by Top Street Performance. It’s a racing part that will deliver more fuel to your engine and a new product write-up about it says, “Leaks are the least of your worries, which means that a tight seal will maintain pressure.” You won’t find the diaphragm inside this pump failing so that excessive crankcase pressure and oil leaks result.

Other high-tech parts that can help avoid oil leaks are gaskets with special design features or gaskets made from special materials. For instance, Cometic Gasket, Inc. markets its C5974 Valve cover Gasket to the race and performance market. These gaskets are manufactured from a soft durometer rubber wrapped around a steel, torque-limiting frame. They seal much better than standard cork gaskets. The rubber and steel combination withstands blowouts, over-tightening and high amounts of vacuum. Best of all, they’re affordable at $31.15 each (cometic. com).

Editor’s note: Last month veteran restorer and auto writer John Gunnell looked at the cures for water and dust leaks in vintage vehicles and this time he’s turned his attention to another well-known automotive malady—oil leaks.

Some years ago, when I helped to compile a book of car crashes from the 1920s through the 1950s, we noticed that the roads in the old carwreck photos were very oily. In addition to oily roads, many of the crashes took place in the rain. We all know what happens when you put oil and water together on asphalt—the surface gets very slick.

So we’re not surprised that this combination probably caused many of the wrecks pictured in the book.

But why were the roads oilier in the good old days? There are many reasons. Take the 1917 Oakland Model 34 we drove over the Yellowstone Trail in Wisconsin last fall (and covered in the December-February issues of AR). Although it was promoted as a “Sensible Six,” the car has an overhead valve engine with no rocker arm cover. It drips black gold like a Texas oil well. What’s sensible about that?

Likewise, our 1940 Indian Chief motorcycle has what is called a Total Loss oiling system. A total-loss oiling system will also be found on old Harley-Davidson motorcycles. It’s an engine lubrication system in which oil is introduced into the engine before being burned off or sprayed all over the place before winding up on the ground. Although rare in modern 4-stroke engines, total loss oiling is still used in some 2-stroke engines.

Through the 1950s, even engines with well-sealed lubrication systems lacked Positive Crankcase Ventilation (PCV) valves. These valves evacuate blow-by (an unburnt gas-oil mixture that gets by the piston rings) from the crankcase. The PCV valve directs the gases through the intake manifold and back into the combustion chambers to be burned more completely. This reduces emissions and boosts engine efficiency.

It should be pointed out that gaskets and seals used in automobile engines between the 1920s and 1950s didn’t do their job anywhere near as well as modern gaskets and seals do. The designs of these products and the materials used in producing them have been greatly improved over the years. Luckily, many of the improved parts can be used in restored cars since they fit OK and don’t have obvious appearance differences. For instance, at the end of this article we’ll see some upgraded racing parts that will fit both big- and small-block Chevrolet, Ford and Chrysler V-8s without major modification.

Keep in mind that an engine doesn’t have to have a massive oil leak to have a big problem. Let’s suppose a teaspoonful of oil is turning up under the car every time it is driven a mile. If you don’t take care of the leak, you’ll lose a quart of oil every 200 miles. Every engine uses some oil and oil consumption tends to increase with higher-speed driving, but normal loss levels should not be a quart for every 200 miles unless you’ve got a car like the Oakland or a vehicle with a total loss oiling system.