How DODGE Got Its Start

John and Horace Dodge Began as Machinists and Used Their Technical and Business Skills to Build a Major Car Company. Let’s Take a Look at the Early Days at Dodge Brothers.

I AM TIRED of being carried around in Henry Ford’s vest pocket.” — John Francis Dodge, 1913.

That simple sentiment launched a car company. John and his brother, Horace Elgin Dodge, were Detroit machinists who, by 1913, had been for the better part of a decade supplying Henry Ford with most of the components used in building his cars.

The vest pocket imagery speaks not only to the close relationship that the Dodge brothers enjoyed with Ford, but also to the very essence of who these two men were, what they meant to each other, and just how huge their eventual impact on the auto industry would be.

From Machinists to Manufacturers

At the turn of the 20th century, watches were typically found in vest pockets. And a pocket watch is a perfect metaphor for the Dodge brothers. They worked like a precision instrument, their two talents meshing seamlessly in clockwork fashion. John, the elder, was the visionary, handling the business end of things, while Horace was the mechanical genius who knew how to keep the enterprise ticking.

The mainspring was their humble upbringing. John was born October 25, 1864, followed by Horace about two and a half years later, on May 28, 1868. Born into a family of machinists — their father, Daniel, and two uncles practiced the trade — the pair grew up in southwest Michigan in the small town of Niles, before their father moved the family first to Battle Creek and then Port Huron before settling in Detroit in 1886.

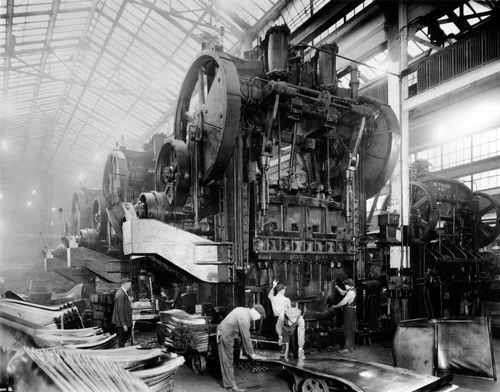

The brothers worked at Murphy Boiler Works in Detroit doing rough machining work for six years before finding new jobs across the Detroit River in Windsor, Ontario, at the Dominion Typograph Company, where they added precision machining to their repertoire.

In 1896, after Horace invented and won a patent for a new kind of bicycle wheel bearing, the brothers struck out on their own. They started a Canadian bicycle company with Harold Evans, who they had met while employed by Dominion. The Evans & Dodge Bicycle venture lasted just four years — the Dodge duo sold their shares in 1900, taking their expertise back to Detroit where they established a machine shop.

A year later, they landed a contract to supply Ransom Eli Olds and his Olds Motor Works with engines for the famed Curved Dash. It was their first foray into the burgeoning automotive industry, and the Dodge Brothers machine shop was located a few blocks north of the OMW factory, which was on the Detroit River. The Olds site is now a parking lot in the shadow of General Motors’ Renaissance Center headquarters.

A devastating fire in 1901 destroyed much of the OMW factory and, in turn, created the opportunity for more work for Dodge Brothers — the company was contracted to supply more than 2000 transmissions to Oldsmobile.

Meanwhile, Henry Ford, after failing twice to start a car company, turned to Dodge Brothers to supply a wide range of components for his original Model A. Ford’s third run at launching a car company proved to be the charm, thanks in no small part to Dodge Brothers. In fact, so successful was Dodge Brothers that the company supplied virtually complete chassis to Ford — Ford only needed to add a body and wheels to finish cars.

The relationship grew as Dodge churned out a generation of Ford vehicles, including the Model C and Model F, although Ford’s Model B (which contained some Dodge content) relied on other companies for parts as a way for Ford to retain some leverage over its main supplier.

Still, in the rough-and-tumble early days of the auto industry, it was hardly smooth sailing. Due to Ford’s low capitalization when it was incorporated, payments to Dodge Brothers were slow. But even this dark cloud had a silver lining that would turn to gold for Dodge. To settle some bookkeeping, Dodge Brothers wrote off $7000 in overdue payments and took a $3000 credit in exchange for a 10 percent share of Ford Motor Co. in 1903. It turned out to be the deal of the still-young century.

Not only did the Dodge Brothers profit handsomely over the next 10 years from its exclusive supply contract with Ford, their holdings in Ford paid millions in dividends. Getting those dividends from the notoriously tight-fisted Henry Ford, however, proved difficult. The Dodge brothers joined a 1916 lawsuit brought by malcontent shareholders, forcing Ford to share its cash hoard. The Dodges finally sold their 10 percent stake in 1919 for $25 million.

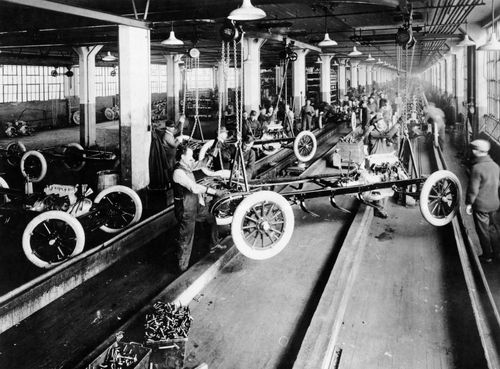

The decade-long relationship with Ford (along with the money earned from fellow industry pioneers) allowed Dodge Brothers to expand, building a larger machine shop around the corner from their original shop, followed by a much larger factory in Hamtramck in 1910. Hamtramck was a Polish enclave located just a few miles from downtown Detroit and not far from Ford’s new assembly plant in Highland Park. Dodge Brothers’ new factory would later be known as Dodge Main, and proved to be the ideal launching pad for their first car.

What drove Dodge Brothers to build its own car isn’t particularly clear-cut. Historian Richard Crabb maintains that it was a desire by the brothers to build a better car than Henry Ford, fueled in part by the automaker’s refusal to incorporate product improvements suggested by his erstwhile suppliers.

Charles Hyde’s authoritative work, “The Dodge Brothers: The Men, The Motorcars, The Legacy,” paints a slightly different picture. According to Theodore MacManus, who ran an ad agency that had Dodge as a client, the brothers met with their attorney Howard B. Bloomer, who asked them why they didn’t consider building their own car. John Dodge is said to have been content with the Ford business and the dividend income, and didn’t want to have the hassle of retailing cars to the public. But Bloomer advised them that their total dependence on Ford could be their undoing. The next day, John and Horace met again with Bloomer and agreed with his assessment.

By August 1913, John Dodge was publicly quoted as saying that he and his brother had been making plans to build their own car and had begun buying property to expand their Hamtramck plant. “Our business has grown too big to be dependent upon anyone else and we have decided to go into the manufacture of automobiles for ourselves,” he told the press. In July, he had notified Henry Ford that Dodge would cease all work for him in 12 months’ time.

As the work for Ford wound down, Horace Dodge shifted into high gear in developing the new car. Helping him was Frederick J. Haynes, whom the brothers had first met back in their Evans & Dodge Bicycle days. Haynes came to Detroit from the H. H. Franklin auto company in Syracuse, New York, and proved instrumental in helping to transition the plant from making components to building complete automobiles.

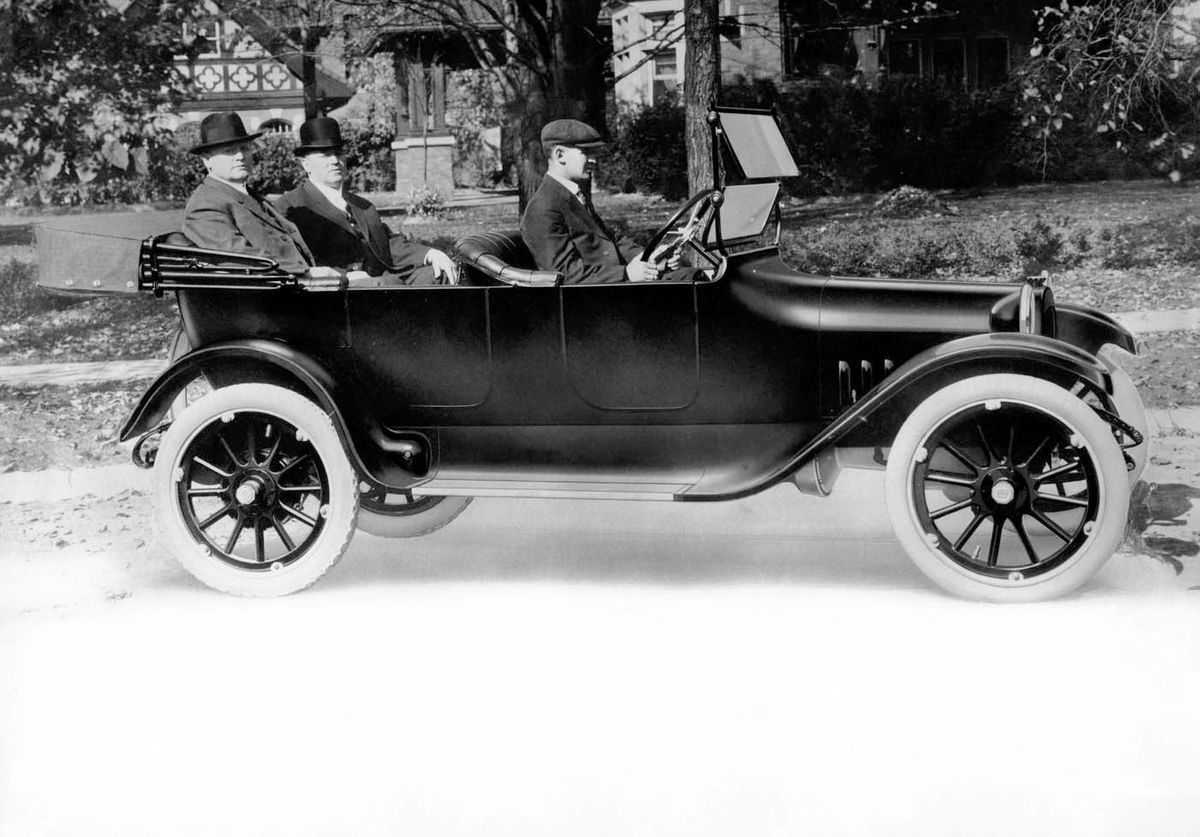

The first car, dubbed “Old Betsy,” rolled out of the plant on November 14. It was driven around Detroit with Horace and John Dodge in the rear and Guy Ameel, superintendent of production, behind the wheel. While purported to be the first Dodge car off the assembly line, the press previewed “Old Betsy” before the roll-out ceremony where they learned that she was, in fact, a development car. This canny use of the press and advertising was key to the Dodge brothers in not only building demand for the car, but also attracting the dealer network they needed to launch and sustain the business.

Dodge’s first dealer was John H. Cheek of Nashville, Tennessee. The son of Joel Cheek, who founded Maxwell House coffee, Cheek’s father urged him to travel to Detroit to talk to the Dodge brothers. Cheek, who sold Chevrolet and REO cars through his Cumberland Motors, won the franchise and sold the first retail unit on December 22, 1914, and later gave up the Chevy business. When questioned by John Dodge about his high initial order of cars, Cheek responded, “If you don’t shoot for the moon, you will never hit it.” Chief among Cheek’s later customers was famous World War I hero, Sergeant Alvin York — Cheek not only sold York his first car, but taught him how to drive.

Building a Better Car

John and Horace Dodge were the antithesis of Henry Ford, who is best described as ascetical in many ways. He didn’t drink or smoke. The behaviors of the Dodge brothers, however, having grown up on the shop floor, were closer to the men they employed. Both loved to entertain and be entertained, and both greatly enjoyed their wealth. They lived in lavish homes, and Horace in particular was fond of powerboats. These divergent lifestyles were also reflected in the cars they built.

Like the Model T, the first Dodge automobile could be had in any color as long as it was black. Its exterior styling did not change significantly for more than seven years, but it did evolve — more than can be said of the Model T, which remained unchanged until production ceased in 1927.

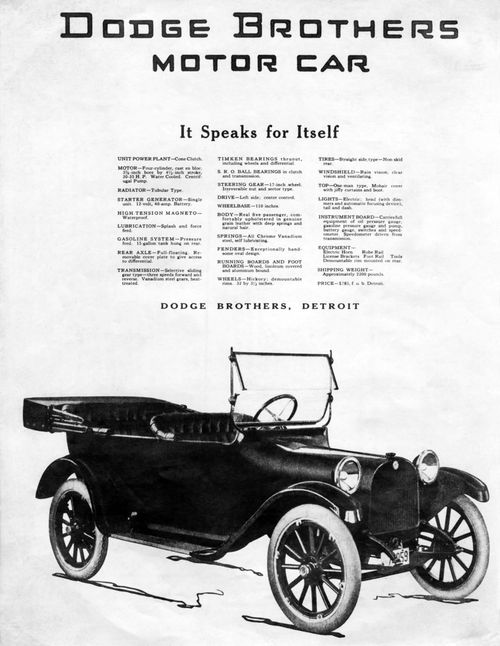

The Dodge differed in that it was a mid-priced car retailing at $785 vs. $490 for the Model T. It rode on a 110-inch wheelbase and was powered by a 35 bhp engine, compared to the T’s output of 20 bhp. The Dodge was technically superior in other ways as well: it was the first production car to use a steel body and chassis (virtually all cars had wooden frames); it had a more sophisticated sliding gear transmission than the simpler planetary gear setup of the T; and it was the first car to use a 12-volt electrical system instead of 6-volt. And electric starting was standard, whereas the Model T offered that feature as an option over the standard hand crank.

While Ford used mass production to lower the cost of his cars year after year (by 1926, a Model T Roadster cost a mere $260), the Dodge approach was to continually upgrade the product mechanically while keeping the price fixed in the middle of the market.

The combination of styling, continual product improvements, and above all, durability — the cars gained tremendous credibility for their use by the U.S. Army in its 1916 Mexican campaign and World War I — burnished Dodge’s reputation. Production ramped up, growing from just 43,033 in 1915 to 141,000 in 1920, putting Dodge solidly in second place behind Ford.

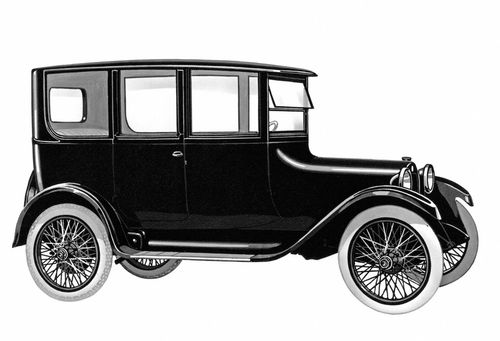

The Dodge lineup was the model of simplicity: an open 4-door touring car and open 2-seat roadster. By 1917, the wheelbase had been lengthened by 4 inches to 114 inches, but the car’s design didn’t appreciably change. Closed cars were offered in a coupe and a center-door sedan — this 5-passenger model had one door on each side in the center of the body, a style that didn’t appeal to many buyers. The price of the closed car rose to $1285.

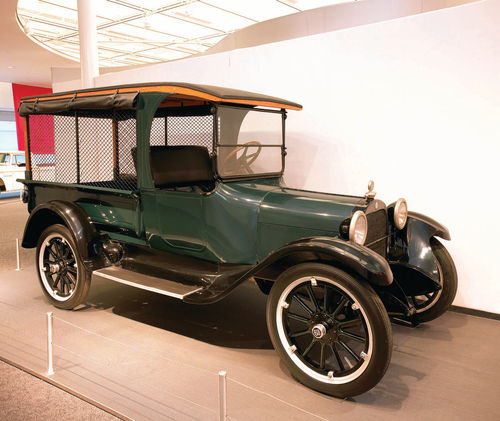

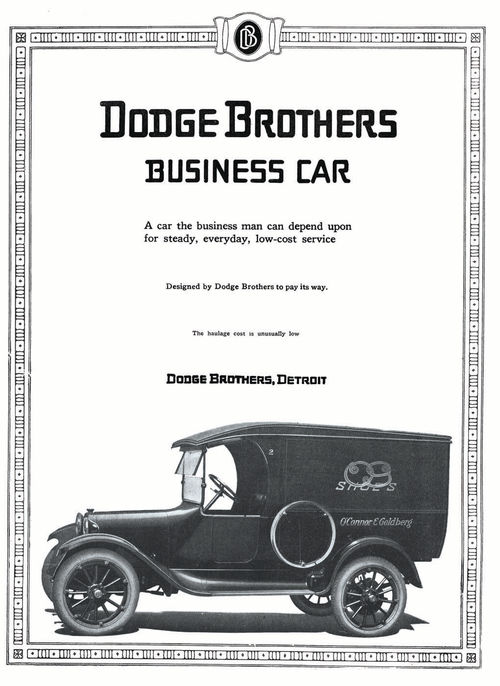

Dodge began its long history of building commercial vehicles when it added a so-called screen-side business car — essentially a pickup truck version of the touring car with screened sides and a roof over the load floor. A panel version was soon offered, as well as a taxi.

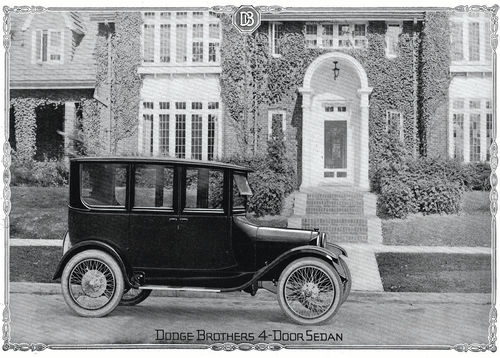

By 1919, the model range had grown again with the addition of a conventional 4-door closed sedan and a 2-door, 5-window closed coupe. Prices ranged from $1085 for the touring car and roadster to $1750 for the closed coupe and sedan.

The Demise of John and Horace

While 1920 was a banner year for sales, it also marked a time of tragedy. During a January trip to the New York Auto Show, both John and Horace came down with influenza, which developed into pneumonia. Though Horace was originally harder hit, he eventually recovered. John, however, became critically ill, slipped into a coma, and died January 14, 1920. He was 55 years old.

Horace, still ill, but recovering, was unable to travel home to Detroit for the funeral. Following the death of his brother, he became inconsolable.

“The passing of my dear brother, Mr. John F. Dodge, is to me, personably [sic], a loss so great that I hesitate to look forward to the years without his companionship, our lives having been, as you all know, practically inseparable since our childhood,” he wrote in a letter explaining his absence from company functions, including a celebration marking the production of the 500,000th Dodge in July 1920.

Although he became president of the company in the wake of his brother’s death, Horace began reorganizing the company to ensure that its legacy lived on by making Frederick Haynes a vice president. Neither Horace nor John’s children showed significant interest in the business, and Horace wanted to ensure that New York investment banks would stay away from Dodge.

Horace Dodge spent most of his time at his home in Palm Beach, Florida, returning only sporadically to Detroit to manage the business and his affairs. Later that year, he had a relapse and was bedridden for a period before returning to Florida, where he died on December 10, 1920. While some reports listed complications from influenza and pneumonia as the cause of death, the official report listed cirrhosis. He was 52 years old, and the Dodge brothers were no more.

Following Horace’s death, ownership passed to the brothers’ widows — Matilda Rausch Dodge, John’s third wife, and Anna Thomson Dodge. Haynes was promoted to president, and Howard Bloomer, the attorney who advised Dodge to build its own car, was elected chairman.

Haynes stuck to the formula that had made Dodge Brothers a success — minimal cosmetic changes while making significant improvements to the product. In 1923, the company introduced a business coupe that was the industry’s first all-steel closed car, followed that fall by an all-steel 4-door sedan.

Other new features added during this period included heaters, semi-floating rear axles, and engine upgrades to the 4-cylinder powerplant that had been unchanged since 1914. The cars’ wheelbases grew to 116 inches without altering the basic look of the exterior design. The lack of styling changes became an advertising slogan in 1924: “Constantly Changed — No Yearly Models.”

On the commercial side, Dodge continued to build the screen-side and panel van versions of its basic car, but Haynes also was the driving force behind the eventual acquisition of Graham Brothers, a maker of commercial vehicles — a move that would mark the beginning of Dodge’s long history of truck leadership. Originally the agreement was for Dodge to simply supply engines and transmissions to Graham Brothers, but the parts and distribution relationship laid the foundation for Dodge to purchase Graham in 1925.

By January 1925, Matilda Rausch and Anna Thomson Dodge were ready to sell. They received over a dozen offers, but the number quickly whittled down to two — one from J. P. Morgan on behalf of General Motors for $124 million cash, or $90 million cash and $50 million in notes; Dillon, Read & Co., a New York investment bank, offered $146 million cash. The widows accepted the latter offer. Dodge was now controlled by outside financial interests, but for Walter Chrysler, it was the opportunity he had been waiting for.

Editor’s note: The above is excerpted from the book “Dodge 100 Years” by veteran auto writer Matt DeLorenzo. The 192-page hardcover book follows Dodge from its beginnings a century ago through the present. It has 200 color and 100 b/w photos and an MSRP of $45. Contact the publisher, Motorbooks, at motorbooks. com; or check your local bookstore.