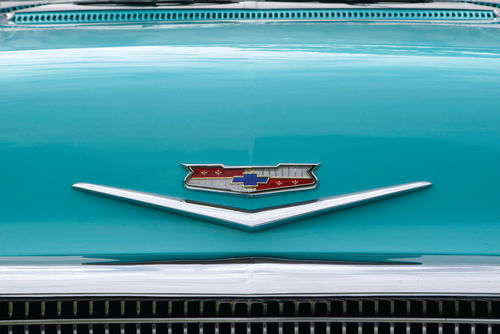

1958 CHEVROLET IMPALA

He Bought This Uncommon Chevy As An Investment. But He’s Grown to Like It So Much That It Now Carries a “Not-To-Sell” Price Tag.

Lloyd Shisler wasn’t looking for another 1958 Chevy and things might have stayed that way if the one that would become the feature car didn’t show up in his area.

“I had just gotten done doing my convertible the year before,” said Shisler, who’s owned the Impala shown here since about 1988. “I knew the guy who had moved just recently within 15 miles or so of my house and had it... He used to drive it once in a while.”

That didn’t mean it was serving as everyday transportation, though, and Shisler said that by the time he decided to look at the Chevy, it was at least being stored out of the weather. The storage, he said, was less than ideal.

“The worst trouble with the car,” he explained, “was that he had a basement and it just had a flat floor with nothing on it and he had the car wrapped in plastic, so everything was scaly. The upholstery looked like it was brand-new, but you could push your finger through it because it was all dry-rotted.

“I ended up making a deal with him and he said it was supposed to have only 24,000 miles on it. I could tell by the bushings in the front end and stuff that it definitely had a lot more.”

The car had been in California before taking up residence not far from Shisler’s Ithaca, New York, home and had the seller been driving it on a daily basis, that region’s winter weather would likely have started it on the road to the salvage yard. Shisler allowed that he probably paid more than he should have, especially considering that 1958 Chevrolets had not yet reached the level of popularity that they enjoy today. In the collector car world, the 1955 through ’57 Chevys had presented an extremely difficult act to follow.

A Time for Some Memorable Models

Chevrolet had entered the postwar world exactly as its competitors had, namely by picking up for 1946 where it left off in 1942. The new Chevys wore what were really just annual updates, even though a four-year gap separated the two. When the true postwar models arrived for 1949, they looked new and modern even as they relied on the same overhead-valve six, an engine that made up for what it lacked in cutting-edge technology with its longestablished reputation for durability and reliability. Two of General Motors’ other divisions—Cadillac and Oldsmobile— changed everything that year by introducing modern overhead-valve V-8s but Chevrolet didn’t follow their lead until 1955.

Chevrolet’s interpretation of the new V-8 design was the 265 with 140 horsepower in its most basic form and as much as 180 when properly optioned. It was quickly found to be not only as tough as Chevy’s six, but also an extremely willing performer. It would go on in various displacements for decades, but 1955 advertising focused on more than engines. Styling was as new as possible that year with smooth sides, much flatter hoods, roofs and trunks, carefully hooded headlights and a wraparound windshield. The visual link to the prewar look was nearly gone and Chevy boasted that “this car’s so perky it looks like it’s always going to a party!”

The driving public agreed, as Chevrolet sold more than 1.7 million examples, but that meant that the 1956 model had to be more spectacular. Advertising announced that “the hot one’s even hotter,” a statement backed up by as much as 225 horsepower from a 265 when equipped with two four-barrels. The annual update provided a completely new grille and taillights, reshaped wheelwells and fresh side trim along with a new body style, the four-door hardtop or Sport Sedan.

They were “frisky new models” with “more of the dynamite action that’s zoomed its way into America’s heart…” Still, they missed the sales mark of the previous version as 1.4 million Chevrolets were sold during the 1956 model year.

For 1957 the body was in its third version and someone who somehow had never seen a 1957 Chevy might be tempted today to dismiss it as nothing more than an effort to squeeze one more year out of an old design. He would, of course, be serving as a shining example of simultaneously being right and missing the point as few cars of the era have gained popularity so quickly and retained it for so long. Determining precisely why the car caught on as quickly as it did is at best difficult, but advertising was remarkably on-target when it flatly stated that “Chevy’s new and Chevy shows it,” a boast made all the more impressive because it was based on thoughtful and effective updates to what was already a two-year-old design.

Fins, a staple of the time, had finally arrived at Chevy and were about as elegantly restrained as could be. The previous grille with its straight-line mesh was replaced by a new mesh now broken by a center bar and wrapped in an oval formed by the bumper and upper trim piece. It was as complicated as it sounds—even before adding the hood with its twin spears—and worked well, as did the new side trim on Bel Air quarters. If all of that didn’t convince prospects, there was the range of V-8s that included not only the base 265, but also the new 283 with its slightly larger bore. The latter was available in horsepower from a comparatively modest 185 to 283—the magic one-horsepower-per-cubic-inch— produced by the newly available fuel injection. They were “Chevy’s superb new engines” and part of a package that struck just the right note with about 1.5 million drivers.

But the upcoming 1958 model would break so cleanly in appearance as to be virtually on its own.

Dual headlights now rode above the grille on each side and were mirrored by dual parking lights within the grille. The three vertical trim strips to the rear of the headlights that had appeared in 1957 were joined by a fourth and now angled forward, but the hood was again smooth. The previous flat sides were mostly gone, as were the clean vertical fins, and in their place were low fins angling outward from just behind the B-pillars. At rear, they swept around to partially enclose small round taillights, single units on station wagons, two on most other models, but three on the newest, the Bel Air Impala.

It Truly Was Different

Available only as a two-door hardtop or a convertible, the Impala carried the Bel Air’s brightwork that was actually restrained for the time and added rocker-panel trim, “nonfunctional” scoops ahead of the rear wheelwells and on the coupe, a “simulated ventilator” on the roof above the backlight. There was more to the Impala, according to Chevrolet, as “these exclusive models feature a special body which is an inch lower than other Bel Airs and has a longer rear deck,” but even that didn’t tell the entire story.

The 1955-57 models had banished the roundness of previous models and almost banished their use of hoods and trunks whose top surfaces bulged above the fenders and quarters at their sides. The 1958 Chevrolets went a step further as they moved more toward a horizontal—or longer-lower-wider— theme. The dual headlights helped, as did the contoured fins and on the Impalas, the longer decks, but it was more than mere illusion, as overall length climbed from 200 inches in 1957 to 209.1 inches in 1958, wheelbase from 115 to 117.5 inches and width from 73.9 to 77.7 inches. Height, on the other hand, dropped from 60.4 inches to 57.1 for most of the 1958 Chevys, but fell to an even lower 55.7 for the Impala, the latter figure obviously meaning more than the one-inch difference Chevrolet had attributed to the Impalas.

Ads told drivers that they would be “in charge of one of the year’s most looked at, most longed-for cars. Chevy’s crisply sculptured contours and downright luxurious interiors are enough to make anybody feel like a celebrity.” It was “the most exciting new shape in a generation of cars” and more than 1.2 million drivers agreed, but there was also the “revolutionary new V-8! That’s Turbo-Thrust, with V-8 combustion chambers in the block and up to 280 hp!”

Although its popularity would never rival that of the 265, 283 and their small-block descendants, the new—and unrelated—V-8 that arrived for 1958 displaced 348 cubic inches and produced its 280 horsepower when equipped with three two-barrels while its single-four-barrel version was good for 250, the latter equaling the fuel-injected 283’s output. Not everyone needed or wanted that and for those who didn’t, an Impala could be ordered with lesser versions of the 283 or even a 145-horsepower, 235-cubic-inch six, but it’s a safe bet that the 348 and the top 283 were and are the most coveted.

When It Comes to Parts… It’s Not a Tri-Five

With all of that in their favor, it was clear that at some point, 1958 Chevys would eventually move beyond being simply interesting collector cars among a host of others. Shisler was thinking about that when he bought the featured Impala even if, as mentioned above, he now concedes that he might have overpaid.

“That was before they were getting popular,” he said, “but I bought it for an investment and I wasn’t going to do anything to it.”

Three decades later, it’s easy to see that it didn’t work out quite as he’d planned, possibly because its condition overall proved to be good. It wasn’t perfect, but it wasn’t bad enough where turning it over would have seemed like a great idea. “On the left side behind the wheelwell,” Shisler said, “it was really thin, on the back fender where the dirt lies right down in there. At that time, they made that piece, so I put that in there, leaded it in.

“They didn’t make the floorpans then, so I found a guy out in Nebraska. I told him what I wanted with the sides and he said ‘don’t worry about it. I’ll get it big enough for you.’ He took a chop saw and went from the toe space all the way to the rear seat and he cut it all the way to the tunnel. It had about a quarter-inch of red dirt on it when I got it and I just took a rubber mallet and tapped on it. It fell right off and (the pan) was perfect, so I cut it down and put that in.”

The greatest challenge there, he agreed, was cutting it down, but not cutting it down by too much. His solution was to begin by making patterns and then trimming the pan in small increments, a process that might be necessary on another example slated for restoration.

“One thing about ’58 Chevys,” Shisler said, “is that the floorpans are of thinner metal than the ’57s. Not very much, but they are lighter gauge to save weight and costs. Of course, if you get a Tri-Five, you can go anyplace and buy any part you want. The ’58s? They’ve got a few more parts out there now. I know they’ve got some floor pieces, different pieces, but they don’t have anything like they do for the Tri-Fives.”

The floorpans aren’t the only potential rust points on a 1958 Chevy’s sheet metal. The fenders above the headlights are targets, as are rocker panels, quarter panels, the trunk floor and the area between the rear bumper and the trunk lid, but the feature car had escaped all of those problems other than that damage near the wheelwell. It also had avoided rust problems with its frame which, while not common, are also not unheard of and most often develop from in front of the rear wheels to the rear of the frame. One of the best quick indications is a rear bumper that somehow just doesn’t seem right, but if Shisler’s car had had any of those problems, he would have found them at the start.

“I took the body right off the frame,” he said. “I didn’t have a rotisserie back then. I had rigged up in my garage four comealongs. I had to put a cradle and lift it up from underneath.”

Similarly, he would have detected any hidden rust or other damage on the body when he stripped it to bare metal. Doing so would have revealed problems behind trim pieces and since none were missing, it wouldn’t have been surprising to find at least one or two otherwise unseen defects. The body behind the trim, though, was about as good as the trim itself.

“The trim was all there,” Shisler said. “Everything was all there, I just buffed it out. There weren’t any dings or bends other than a few door dings. The bumpers have been re-chromed, but they were good. All of the emblems are original. Other than those two Impala flags that are reproductions, everything else is all original.”

The glass wasn’t as lucky.

“Most of the glass other than the rear window’s been replaced since I got it,” Shisler said. “The back window’s original and the windshield, I had to fix that because when I had it out a couple of years when I was freshening up the car… the rubber molding…I didn’t like where it was. It was off just a little bit, but it looked terrible to me, so I pulled it out and I cracked it, so I had to get another windshield for it.”

The dry-rotted upholstery had to go, of course, but he found that it was only the upholstery that needed to be replaced as the seats themselves were in excellent condition. The headliner that had become stained over the years was replaced, but the aluminum inserts on the side panels were in good condition and so he reused those on reproduction panels.

Rebuilds for the Engine and Transmission

The Impala’s mechanical condition was even better, as both the Powerglide automatic and the 283 had held up well.

“I had the transmission on it redone about six or seven years ago,” Shisler said. “It was leaking. It was dripping, mostly, and every once in a while in the wintertime when I don’t have anything to do, I’ll pick a project, so I took the transmission out and I took it to a shop here and he rebuilt it for me.”

The engine began to show a need for attention more recently.

“I didn’t rebuild the motor until two years ago,” Shisler said. “A couple of years ago, it just sounded a little bit noisier than normal. When I had had the transmission out, I saw that the motor looked like it was all original, like it had never been touched, but I didn’t know how many (miles it had covered). It definitely had more than 24,000 miles on it. It probably had 124,000 on it.”

With an exception here or there, Chevy engines and transmissions have been so popular for so long that nearly every mechanical component is likely to be available, meaning major repairs are not major problems. Their popularity, though, combined with the wide interchangeability of parts is another plus for those who aren’t purists as a later 327 or 350, for example, will smoothly replace a 283 and a Turbo Hydra-Matic can take the place of a Powerglide.

Nearly Bulletproof…

The feature car’s 283 is the base twobarrel version with 185 horsepower and Shisler recalled considering a four barrel upgrade for 230 horsepower. While he decided against that, he did install dual exhausts for a noticeable difference in performance, but fuel economy is at best tolerable.

“I think the last time I checked it,” he said, “it was about 14 or 15.”

That doesn’t matter very much on a car that travels only about 500 miles each year, but the low mileage doesn’t mean he worries about getting home with it because it’s not an especially complex car and has few components known for failure. “No,” he agreed, “other than the fuel pump or the carrier bearing. That’s about the weakest point in the car, so actually, I always keep a spare in the garage because I’ve got three cars with them. Actually, it’s just that rubber cushion that comes apart in there after so many years. It’s just another universal joint.”

The car uses a two-piece driveshaft and the bearing, according to Chevrolet’s own description, supports the rear of the front driveshaft section as it passes through the X-frame. The design was used on other GM cars and on the Impala and its relatives wear and age cause problems. But unlike the fuel pump, it generally provides a warning rather than a surprise failure.

Shisler said that last season the Impala let him down for the first time when its fuel pump stopped working on his way home from a show. He said he’s had problems with modern replacements and solved it this time with an electric unit. If he were going on a serious trip he’d carry an extra, but that’s about the only precaution as the car is ready to go.

This “Comfortable” Car Has Found a Home

The Impala wouldn’t pass unnoticed on the road, he said, but only some folks could identify it without hesitation.

“Not as many as used to,” he said, “mostly older people. Everybody would know what a ’57 is.”

More importantly, 100 miles would be easy as the Impala treats its occupants well. “You could ride that far without any trouble,” Shisler said. “It’s comfortable.”

He probably knew that and a lot more about 1958 Chevys long before he owned the feature car or the convertible.

“I loved ’58s ever since they came out,” he explained, “and I had one when I was a teenager. (As an adult) I probably looked for seven or eight years for a ’58.”

On a trip to Florida, he covered back roads and searched ads without success hoping to find one and then stopped at Charlotte AutoFair on his way home to Ithaca. “I bought my son a t-shirt,” he recalled. “The next day, a guy who was working with him said he had a car for sale, which was that convertible I bought.”

The convertible’s not going anywhere and despite that plan about buying the hardtop as an investment, neither is the feature car. When pressed, he responds with a figure that makes the point.

“My wife,” Shisler explained, “said ‘that’s the not-to-sell’ price.”