The 1965 Buick Riviera

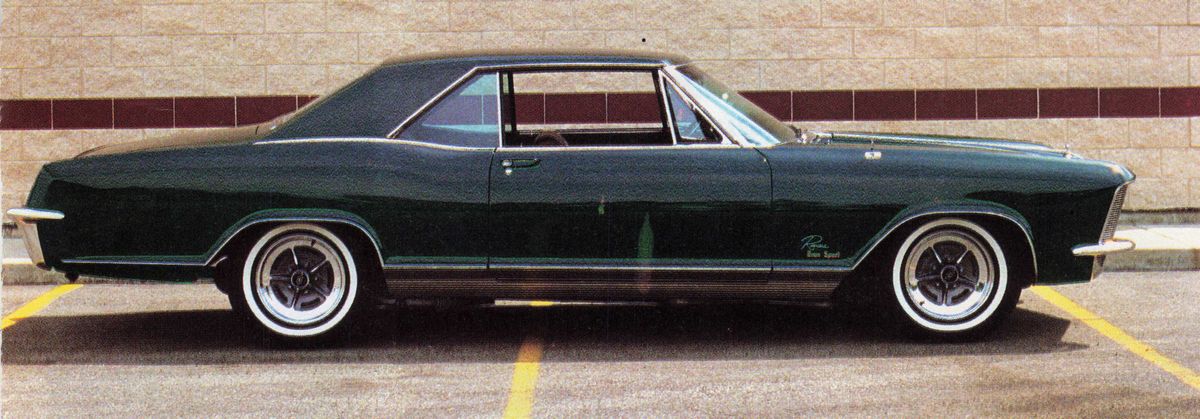

Not often is the third year of a car’s life cycle considered the best of the breed. Usually de signers distort the styling and paste on trim trying to make a car look “new.” However, for Buick’s much lauded Riviera, introduced in 1963, the 1965 model is considered by many to be the purest version.

The original concept was proposed by GM Chief Stylist Bill Mitchell: a big 2+2 coupe to fight the popular Ford Thunderbird, with styling blending Rolls-Royce formality and: Ferrari aggressiveness.

Mitchell assigned Ned Nickles (creator of the hardtop ’49 Riviera, the 53 Skylark, and Buick’s prestige portholes) to develop his idea.

Nickles sculpted a beautiful form combining sharp edges and subtle curves. Since the project was created before a division was assigned, Nickles badged it as a LaSalle and applied miniature LaSalle grilles to the edges of the fenders, intending them to house hidden headlights.

Mitchell was so keen on the project that he and his assistants followed it through every step on the road to production, making sure the concept wasn’t monkeyed with. In a competitive process, Buick got the nod to build the car over Olds and Pontiac largely because only Buick accepted the proposal “as is.”

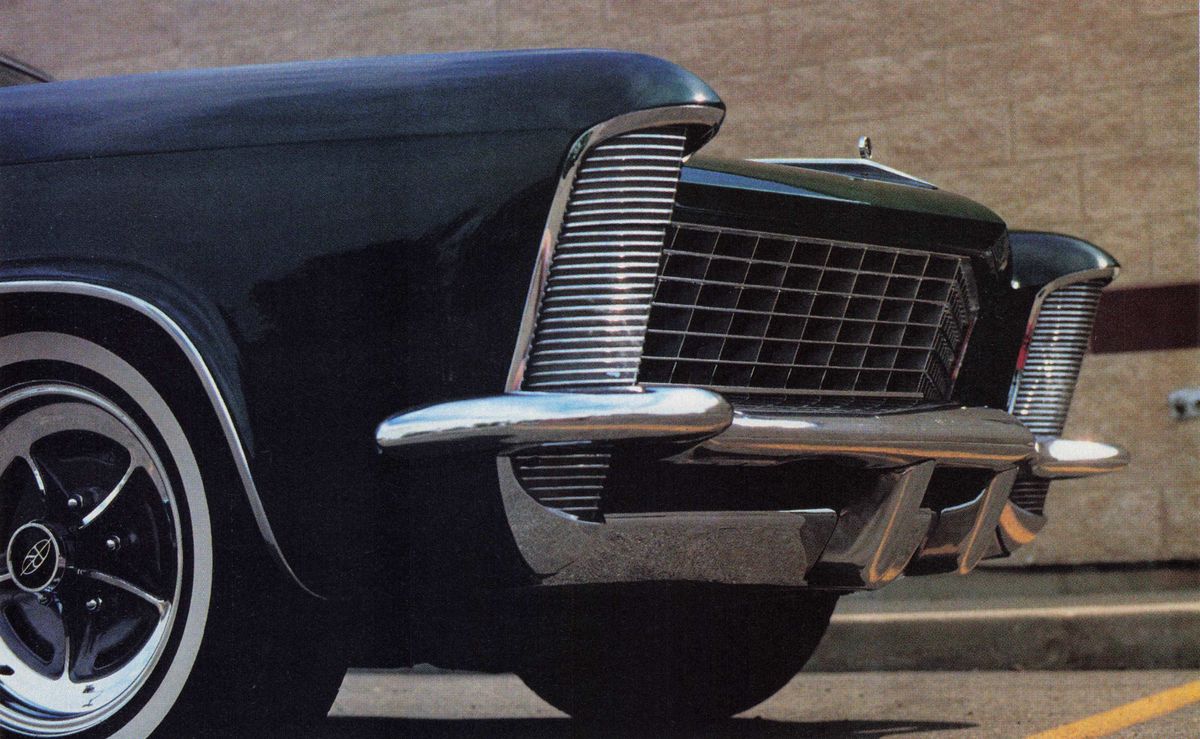

Still, a few compromises had to be made. The hidden headlamps feature wasn't ready in time for production, so the lights were exposed and placed within the grille the first two years. For ’65 the mechanism was worked out and stacked quad headlights were concealed in the miniature LaSalle grilles as originally intended.

Steve Ledger, who has owned our feature ’65 Gran Sport for more than 20 years, says these hidden headlights are a common source of trouble for Riviera owners. The clamshell covers are operated by an electric motor, and Ledger says “the motor craps out because it sits in front of the radiator and it absorbs all the moisture and road dirt. The linkage binds up and then the motor burns out.”

Installing a rebuilt motor and setting the limit switches solves the problem. However, Ray Knott of the Riviera Owners Association points out that headlight motors for the ’65 Riviera are one of the hardest parts to find. According to Knott, “We’ve had different people over the years rebuild the headlight motors, but it can be very difficult, costing up to $400.”

The headlights are unique to the 65 Riviera, but other problems shared with all ’63-05s are a result of new ideas being tried on these cars, some of which had less than positive results. Because the styling was sacrosanct, Buick engineers designed new mountings for engine accessories to squeeze them all under the low hood.

This made working on the heating and air-conditioning units particularly difficult. Ledger, who once changed the heater core in his car, says in disgust: “That was a one-week job. I don’t think I had to take the rear bumper off, and I left the headlights in, but damn near everything else had to come out.”

He’s joking, but not much. Ledger had to remove the seats and console from the interior just to get at the core. Then, working under the hood, he had to unbolt the heater, locating most of the bolts by “guess and by feel.”

“It’s a terrible job,” Ledger adds. “Most Buick mechanics won’t go near it. I think there’s a seven-page service bulletin on it; as far as I’m concerned it’s about 20 pages short.” Knott periodically publishes a how-to article on changing the heater cores that he says “has been the most popular technical tip in the 12-year history of the club.”

Rivieras were the first cars to have flush-fitting windshields and rear windows. GM’s Fisher Body had to develop techniques for installing these with adhesives. It was common for the rear window to leak, causing rust problems at the back of the car.

According to Knott, “The sealant dries up, causing the water to lie in that little groove around the window. If it rusts through, the water will go down into the trunk and get into those sockets that hold the body to the frame, or come out under the seats and lay on the floorboards.”

The seals can be repaired fairly easily, though the work is tedious. “T’ve done that on both the front and rear window,” Ledger says. “The window is held in with some clips, then there’s goo around that, and the trim goes over it all. Take off the chrome trim without scratching the glass or paint. Clean the old weatherstrip out of there, that black gooey stuff that’s hard like old clay. Then you replace it.”

Because flush-fit windows are no longer a novelty, Ledger says new sealer is available from any glass installation shop and is higher quality than the original. Screwdrivers and other common tools can be used to remove the old gunk, and the window doesn’t have to be taken out of the retaining clips.

Rivieras were also GM’s first production cars to use side glass without frames. Getting them to seal properly meant that the outer skin of the door had to be removable. After the door was hung and aligned at the factory so the windows shut properly, the door skins were attached and a jig was used to align the front fenders with them.

Ledger says air and water leaks around the side windows on old Rivieras are common because the rubber seals tended to deteriorate with age. He says new rubber usually solves the problem without having to disassemble the doors.

However, to adjust the fit of the doors the outer skin must be removed. His advice is to be careful during this process because of the little bolts that are attached to the skin. Acorn nuts hold the skin to the door frame. “If there’s any rust at all, the bolts snap right off when you turn them,” Ledger says.

Wiring gathered into flat ribbons instead of bulky bundles was another Riviera first. This made installation of interior components easier and today is a standard item of automotive design. Ledger says the wiring in his car has been trouble-free. Knott agrees that this is rarely a problem area on Rivieras. However, the electrical system is complex, so be wary of cars with electrical problems.

Mechanical reliability is a big plus of Riviera ownership. The ’63-65 model used various versions of Buick’s reliable Wildcat V-8. Knott says many cars in the club have racked up 200,000 to 300,000 miles without breaking down. The fuel pump is the most significant weakness, so Knott always carries a spare on long trips.

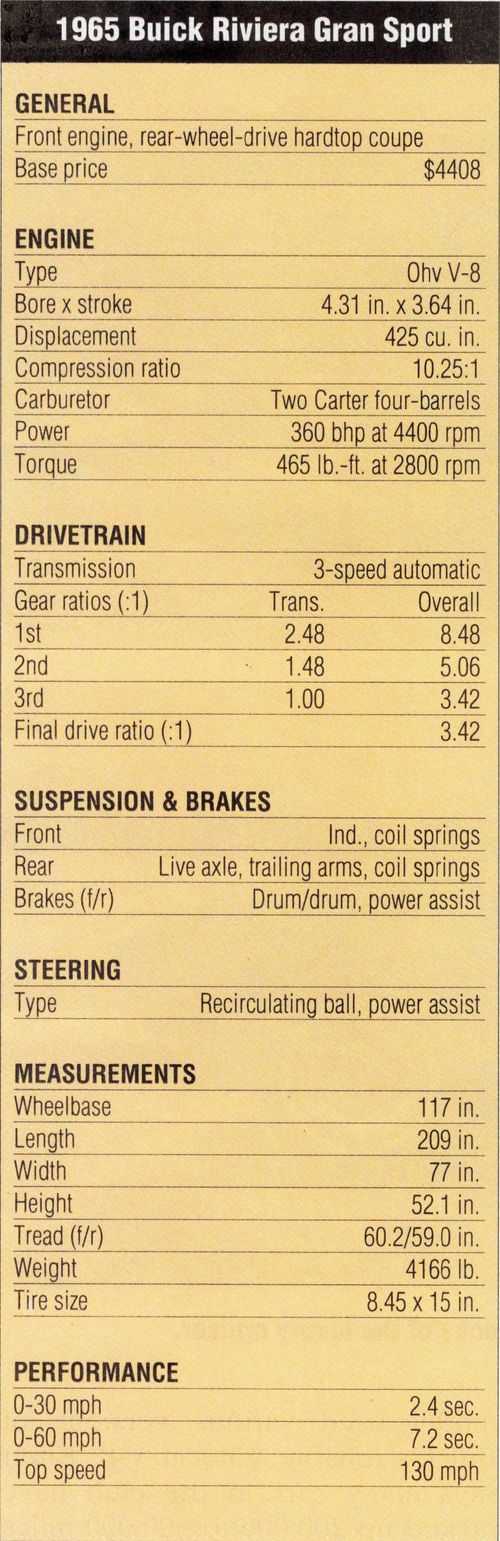

Mitchell had decreed the Riviera should have smooth, powerful performance to match its looks. The 401-cubic-inch Wildcat was good for 325 horsepower, but Buick engineers cooked up a bored-out 425 V-8 providing 340 horsepower as an option.

Despite a two-ton curb weight, this locomotive-like power put the Riviera in the same performance league as European exotics like Ferrari and Aston Martin, at least in a straight line. Finned brake drums, special suspension bushings, and newly designed tires helped roadability, but the Riviera would never be mistaken for a sports car in the twisties.

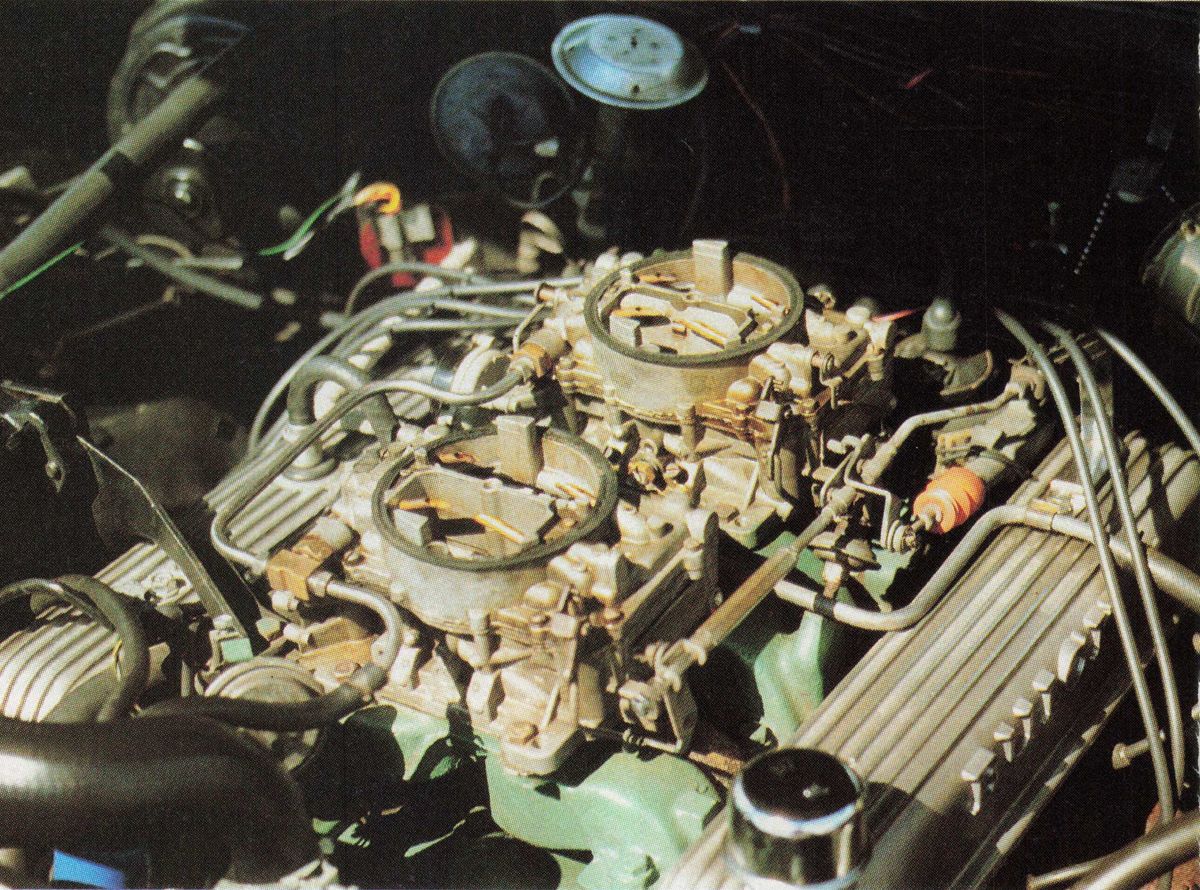

For even mightier performance, the ’65 Riviera offered the first of Buick’s soon-to-be-famous Gran Sport packages. Dual four-barrel carbs had been an uncommon dealer-installed option in ’64. The Gran Sport got dual carbs on the factory floor and was dressed up with ribbed aluminum valve covers and a chrome air cleaner.

With revised dual exhausts, a beefier transmission and Posi-traction, this was good for 360 snortin’ horses and 0-60 in eight seconds or less. Special Gran Sport badges marked these potent performers. Quicker steering (15:1 compared with the standard 17.5:1) and suspension upgrades were further options usually ordered to complement the Gran Sport package.

Only 3335 Gran Sport Rivieras were built in 1965. For ’66 the body style was changed significantly. The dual-carb setup was dealer-installed again in ’66 and then phased out when Rivieras adopted Buick’s nextgeneration 430-cubic-inch V-8 in ’67. All this makes the 65 Gran Sport Riviera a very special car. It also makes finding some parts a pain in the butt. Ledger ticks off the list: “The chrome air cleaner is particularly hard to find. The Gran Sport insignias are hard to come by, and the exhaust and mufflers are hard to find.”

Reproduction insignias are available through A B & G in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, but the Gran Sport exhaust system can be a real problem because it is very vulnerable to corrosion. Rather than laying flat, the mufflers on these cars are installed at an angle and that makes it much easier for condensation to collect in the corners. To combat this, some owners poke small holes in the muffler. They say the holes allow the condensation to drain, add years to a muffler’s life and don’t create a noise problem.

Ledger says, “The low points in the (original) muffler have no drip holes, so the system rusts out every few years. You can’t get the Gran Sport muffler, which sits behind the differential, unless you find somebody that’s got NOS. The exhaust shops have to make one, and most of the ones I’ve seen don’t do a very good job.”

He adds, “Then, of course, it rusts out in a few years and you’re back to square one. It’s one of those things where you ought to spend the big money up front, get the stainless and do it right.” (A complete stainless system costs about $1000 and could cost judging points because it’s nonoriginal.)

The dual carburetors are less of a problem. The Gran Sport used a sequential linkage and four-barrel Carter AFBs, which Ledger says stay in tune pretty well. The rear carb is used full time and has the automatic choke and vacuum line attached. The front carb doesn’t start to work until the rear one is halfway open.

Ledger laughs: “When you run down the road fast enough to get that front carburetor to open, that’s when you need the 747 tanker to fly up behind you because it’s sucking down the gas pretty good.” (Ledger says he generally gets 15 mpg, but if he steps on it hard that figure drops to about 10.)

For anyone interested in restoring a Riviera, prices are reasonable. Knott says you “can get into a nice Riviera for $3000. It will probably have a tired interior and need paint. It should have a strong motor for that price.” At the high end, “people can get a very nice (restored) car for about $7000.”

Parts availability is good, though many items are available only through mail order. Knott says, “We're not a Mustang club; we can’t rebuild the car from reproduction parts. It requires a lot of time and patience to contact a lot of people.” His best advice is to order parts through suppliers that can be found in the club magazine.

Obviously, restoring a Riviera is a labor of love. Parts take some looking for, and the difference in value between driveable cars and trophy winners is such that it is unlikely you'll get the cost of the restoration back when you sell the car.

So why get a Riviera? The driving experience, for one thing. Knott and Ledger say almost the same thing when asked if the Riviera is a good driving car: “Ohh ... yes!” Knott has driven his ’65 across the continent and loves the luxury, comfort and power. Ledger adds, “it excels after 60 mph.”

There’s also the pleasure of having a distinctive automobile. The shape is a landmark of automotive design. Sir William Lyons, Sergio Pininfarina, and Raymond Loewy all acclaimed the first-generation Riviera a classic. From the men who styled Jaguars, Italian exotics, and the Avanti, this was high praise indeed.