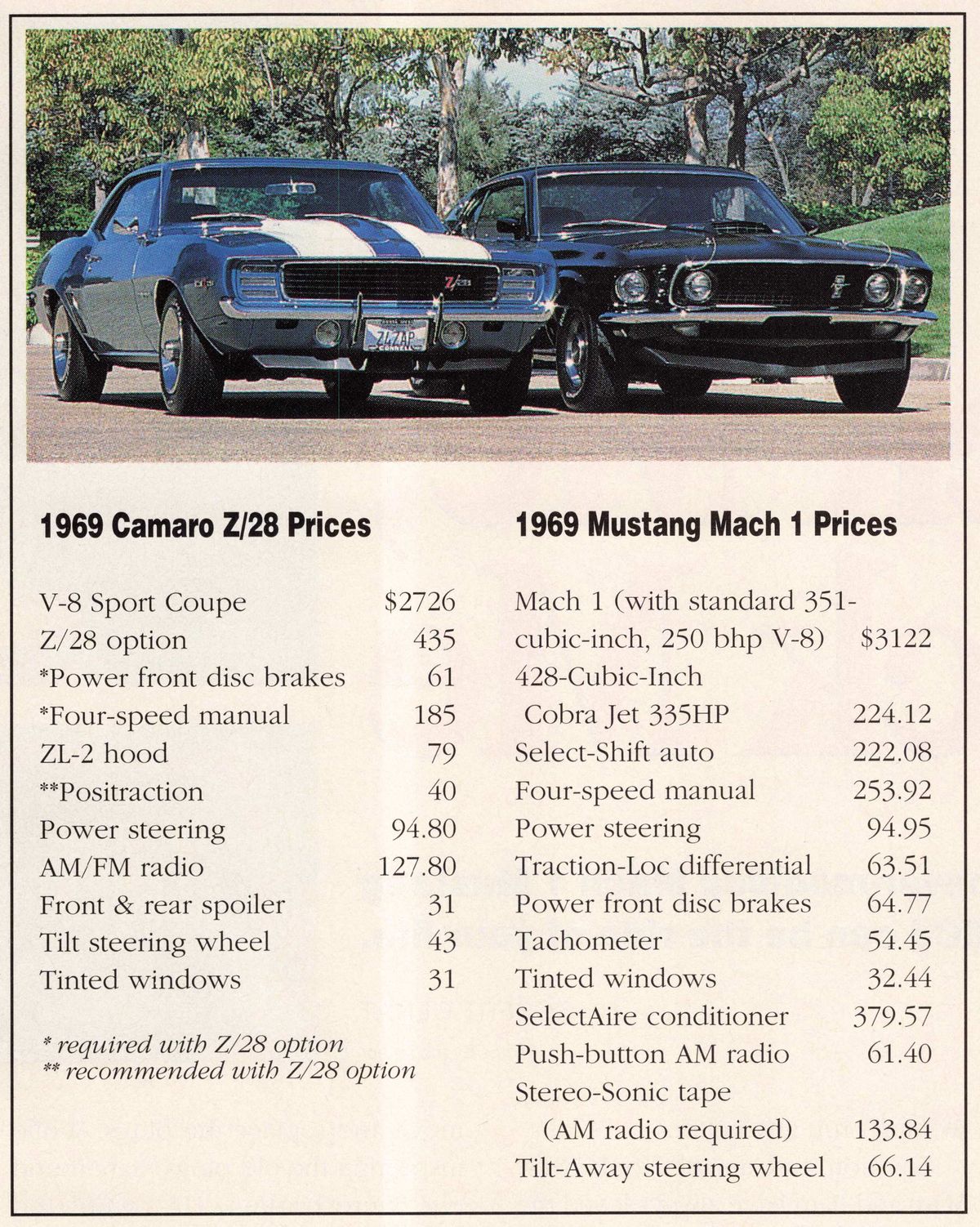

1969 Chevy Camaro z/28 Rally Sport

Charting the 2/28 Heritage.

The Z/28 Camaro was the brain child of Vince Piggins, Chevrolet’s high-performance rep.

In 1966 the SCCA (Sports Car Club of America) was developing a production sedan class. Cars would be production based sedans with a 305-cubic-inch limit. Piggins convinced the SCCA officials that with Chevrolet’s support, this new class could be a success. Piggings suggested to Chevrolet General Manager Pete Estes how easy it would be to put a 283 crankshaft (3-inch stroke) into a 327 block (4-inch bore) and have a 302-cubic-inch engine. Estes, an engineer, bought into the concept immediately and the heartbeat of the Z/28 was born.

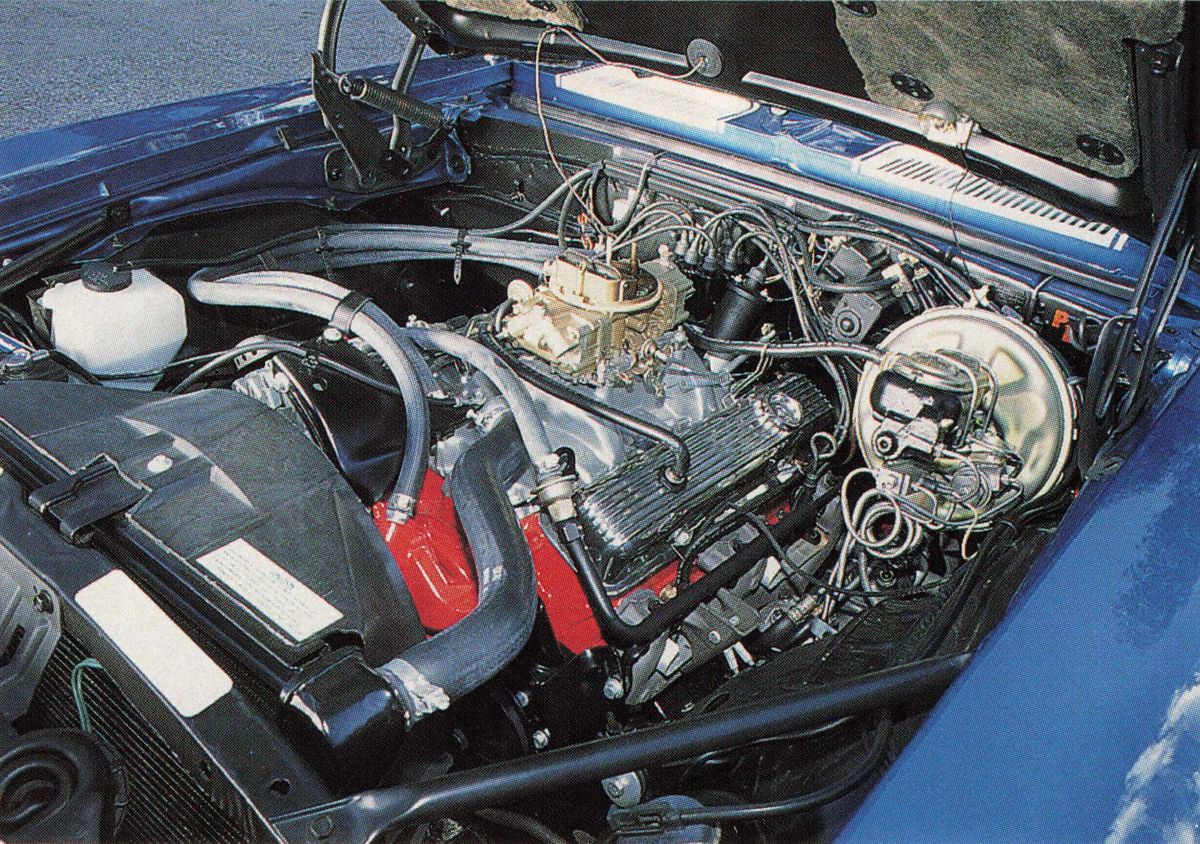

The Z/28 option was available soon after the release of the 67 Camaro although it carried no distinctive badging that year. The Z/28’s high-performance 502 engine was conservatively rated at 290 bhp at 5800 rpm. This short-stroke savage could easily rev to more than 7000 rpm. The highest octane gas was required with 11:1 compression forged pistons. The Z/28's solid lifter cam had 346 degrees of duration with more than 100 degrees of overlap. Topping off the engine was a huge Holley four-barrel carburetor on a high-rise aluminum intake manifold.

The Z/28 option was a complete engine-body-chassis package, not just a hot engine. Starting in ’68 the exterior carried the Z/28 badges on the front, rear, and both sides. The deck lid and hood each had a pair of wide racing stripes. When the Z/28 option was selected, an optional four-speed transmission and power-assisted front disc brakes also had to be ordered.

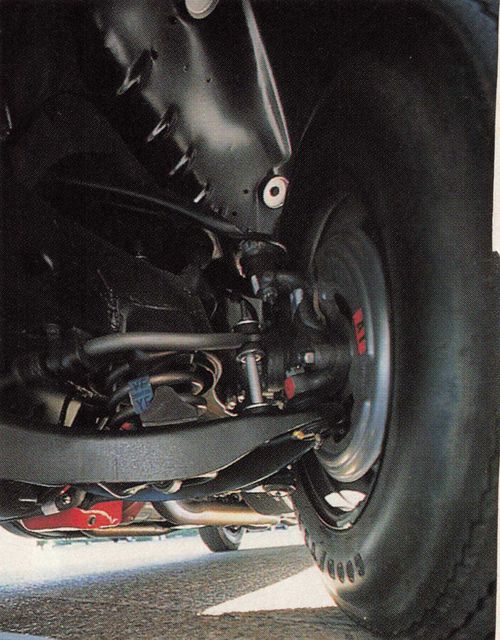

One of the first retailers to receive the Z/28 was Roger Penske who owned several Chevrolet dealerships in Pennsylvania. Penske had been involved in several levels of SCCA racing and he asked fellow SCCA driver Mark Donohue to pilot his Z/28. The ’67 season got off to a less-than-glorious start. The Z/28 had a ton of power, but the suspension and braking were inadequate. Chevrolet, determined to make the Z/28 a winner, assigned their Research and Development engineers to solve the problems. The R&D guys found the body was flexing too much, upsetting the suspension geometry. They also recommended removal of the rear suspension’s traction bar for the same reason. Work progressed as the season wore on and the Camaro Z/28 continued to improve. The last two races of the year were won by Donohue. With the bugs worked out, the Penske team prepared for the 1968 season. It started painfully at Daytona where mechanical problems kept them in the pits. Early pain led to season glory as the Penske team won nine of the following 12 races, taking the Trans-Am championship.

General Motors was impressed with the Z/28’s success and optimistic about future sales. Chevrolet’s Pete Estes said, “We planned on selling about 400 in 1968, but instead we had 7000 orders. In 1969 we plan to sell 27,000. Estes’ sales projections were a little optimistic — Chevy sold only 19,014 Z/28s.

The rising insurance rates and clean air standards of the early 70s cut into Z/28 sales and performance figures, but the Z was an image car and it accomplished its goals. Its winning ways attracted buyers to Chevrolet dealerships with money in hand. They may not have bought a Z/28, but through it they saw Chevrolet’s vision of speed and style.

Carl Weaver's Z/28

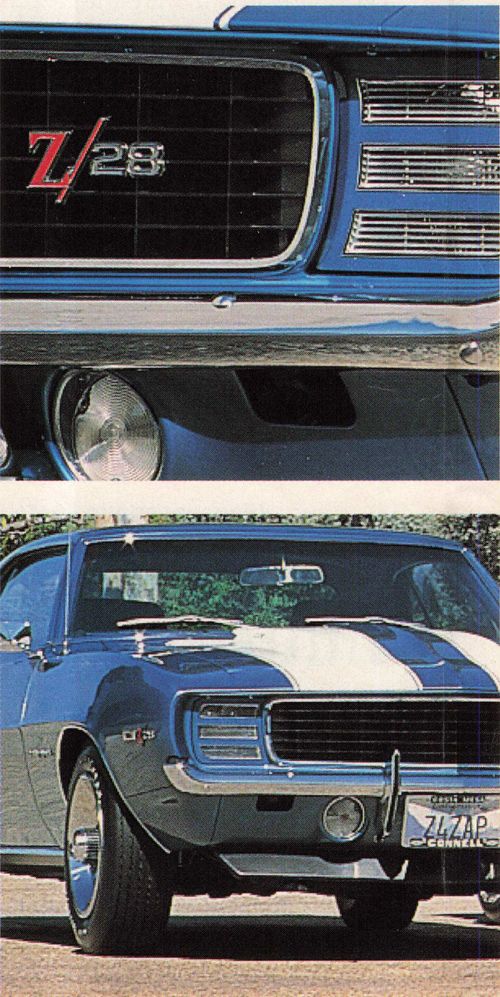

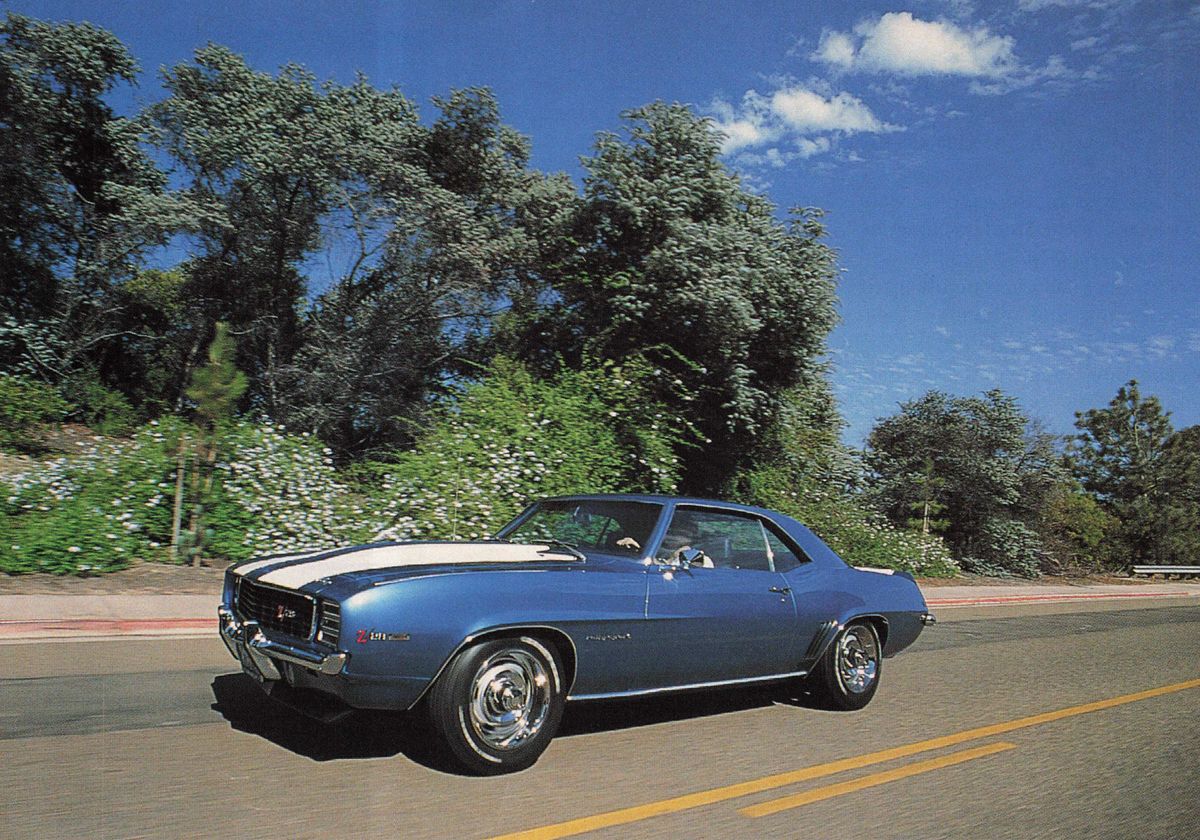

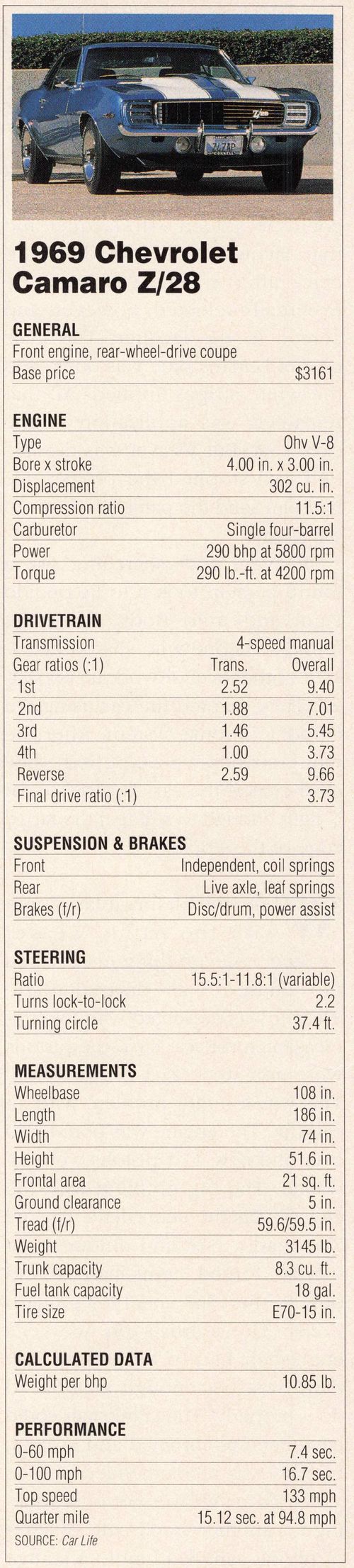

In high school Carl Weaver was known as the “Camaro Kid.” He particularly loved the styling and performance of the first generation Z/28s (1967-69). Weaver even remembers his first ride in a Camaro, and has vivid impressions of the orange $8350 with a black interior, console, and Hurst shifter. Weaver spent the next 20 years raising a family and building a career, but he held on to his personal fantasy of owning one of the first-generation Camaros. He read everything he could about the early Camaros and developed a vision of the car he would one day restore — a 1969 LeMans Blue Z/28 Camaro. In 1991 Weaver was in a position to chase his dream in earnest. He began by creating a priority list for the car of his dreams. First on the list was a 1969 Z/28, the most highly developed of the first-generation Z/28 Camaros. It was the second and last year the big journal crank shaft was offered. To make things more difficult, Weaver also wanted the Rally Sport-Z/28 dual option combination. The RS option offered hidden headlights with washers, and Rally Sport identification. Weaver was especially fond of the color LeMans Blue and he liked the contrast of the white stripes used on the Z/28. The last and most difficult requirement to fulfill was a numbers matching car, complete and unmodified. It would be a very tall order to find any one of the requirements on the list, but a near impossibility to find everything he wanted.

He followed leads on cars as far away as Florida and once traveled to Oregon, but the descriptions in the ads did not match the vehicles. Weaver found cars missing emission equipment, heavily modified engines or with numbers that did not match. His research taught him where to look for high-rust areas. In most of the cars Weaver looked at, he found bondo in those areas. “When they said ‘rust free,” Weaver says with a grin, “they actually meant you got all the rust on the Car tor free.”

While looking through the want ads in the local Sunday paper he found one that said “Z/28-beautiful car.” Weaver had come across many ads like this and without a great deal of anticipation he drove from his San Diego home to the northern suburbs of Los Angeles. What he found was the object of his search — a LeMans Blue ’69 dual-option Z/28. The car had 97,000 miles on the odometer and all the numbers matched. The paint was original with no major damage to the body.

The interior was in poor shape. Stuffing sprouted from the seats and what was left of the carpet was a mess. Weaver checked all the high-rust areas and found none. The numbers on the engine matched and all the emission equipment was in place. There was more than the usual amount of documentation with the car, including several receipts for repairs and oil changes. One key piece of documentation was the Protecto Plate, a credit-card-size metal plate attached to the back of the owner’s manual. When the car was brought in for warranty service, the Protecto Plate would be run through a machine to obtain an impression. The codes on this card list all options, the VIN number, and certify authenticity of the vehicle. Weaver’s search had ended, but the hard work was just beginning. Weaver knew his only option was a full restoration. He had a wealth of mechanical experience, but had never tackled a job of this magnitude. However, as a boy Weaver had built model cars and airplanes. That’s how he looked at this project. “It’s like a big model,” he said. “Everything fits in a certain way.”

Once the Z/28 was in his garage, Weaver removed the interior, including the instrument panel and headliner. Next, the trunk was cleaned out. The hood was removed and the engine, transmission, and drive shaft were removed. The sub-frame and rear axle were left in place so the car could be rolled about, Next, all the sheet metal was removed from the car. All that remained was the body shell and sub-frame. Finally the glass, sub-frame, and rear axle were removed. The bare body shell was now sitting on blocks.

With the car completely disassembled, Weaver was disappointed to find some rust in the floor pan. A six-inch-long area in the front floor had rusted through. This area of rust had been hidden from view by the sub-frame. The hole was fixed with a patch panel that was welded in. A little additional rust in the floor was quickly ground away.

Weaver took the body shell and sheetmetal to a local body shop that had been recommended to him. One partner did the body work, consisting of door dings and small dents, in a short amount of time. The other partner was the painter. He didn’t attack Weaver’s car with the same amount of enthusiasm as the body man. Weeks turned into months and the car was not progressing. Weaver paid them for the work done and picked up his half-finished car. Weaver took his car to a second painter who also came highly recommended. The painter didn’t think he could please Weaver and refused the job!

The third painter suggested using lacquer, but Weaver felt too much could be hidden with lacquer and that lacquer had a tendency to crack after a period of time. He eventually relented, however, and agreed to the lacquer. The base coat of LeMans Blue was down and the white stripes applied. All that remained was application of the clear coat. But Weaver was dissatisfied and stopped the project. He had him sand the paint off, down to the primer.

Weaver, now searching for a fourth painter, took it to Escondido Paint and Auto Body. There he found someone who shared his vision of the level of work he expected. They painted the car using the Dupont Chroma system. After the white stripes were applied, they clear-coated the car. The clear coat is light enough to still feel the taped edge of the stripes.

While the drama played out with the paint, Weaver worked on everything else. When the engine was disassembled, Weaver was presented with two unpleasant surprises. First, the pistons were non-stock 12:1 compression. This was a minor problem with an easy fix. The engine was bored .030 over and new 11:1 pistons were installed. The big problem with the engine was the crankshaft. The ’69 Z/28 had a rare and unique large journal forged crankshaft, found only in the 1968 and 1969 Camaro Z/28s. The journals on Weaver’s crankshaft had to be ground, but there was not enough material to do it properly. The crankshaft could have been re-chromed and ground, but this was recommended only as a last resort. Weaver got busy looking for another crankshaft. A series of phone calls led him to a source in Chicago who sold him an NOS crank for $500.

Now Weaver delivered his powerplant to the Engine Parts Warehouse in Escondido for the rebuild. Everything inside the engine was brought back to GM specs, including a new GM solid lifter cam. The four-speed transmission was rebuilt and a new clutch bolted-in prior to the installation of the engine.

Weaver also had an entire exhaust system built out of stainless steel tubing. But bending the stainless pipes properly was a difficult task, “If I had it to do over, I'd: use aluminized pipes,” Weaver admits. “They’re easier to work with.”

Unfortunately there was some thing wrong with the engine. It sputtered, coughed and just plain ran lousy. The carburetor was rebuilt again and analysis led Weaver to believe the camshaft was bad. A small block Chevy camshaft can be pulled with the engine in the car, but Weaver opted to remove the engine first. Therefore, everything had to be protected to prevent any of the finished pieces from being damaged.

With the engine out of the car, the camshaft was removed and checked — it was up to spec. Only one system was left as the culprit — the ignition. When the engine was being rebuilt, the distributor was detailed and new points, condenser, rotor, cap, and wires were added. A closer look was now taken at the distributor. The distributor shaft bearings were worn, allowing the shaft to wobble. This oscillating affected the dwell timing and thereby the spark output. New bearings were installed in the distributor housing and the distributor was rechecked. Problem solved!

One of the challenges Weaver encountered was how to replicate the phosphate plating on the hood hinges. Chevrolet plated the hinge pieces separately, then riveted them together. The phosphate replating Weaver found was not the same finish as that found on Chevrolet’s original parts. Weaver attacked the problem head-on by creating his own formula paint to equal the factory’s phosphate coating. Satisfied with the results of this home brew, Weaver decided to make it available to others and founded OEM Paints. Along with Weaver’s phosphate paint, marketed as PhosPaint, Weaver has introduced an entire line of paints especially for the auto restorer.

Carl Weaver was a man on a mission. And through persistence, he now has the car he always wanted — a brand new 1969 Z/28. The Camaro Kid rides again!