1960 Pontiac Bonneville Convertible

How do you get a 1960 Pontiac Bonneville convertible from North Carolina to Florida? Mike Jole thought about it and decided he would trailer the big, two-ton plus Pontiac behind his mid-size Dodge Dakota pickup. It didn’t take long before he learned something wasn’t quite right in the balance equation.

“As soon as I would pick up some speed, it pushed that truck all over the road,” Joule said. “I would never do that again. After nearly running off the road and wrecking, he accepted a 32-mph maximum speed and settled in for the long haul down I-26. The trip from Asheville to Jacksonville, normally a seven-to-eight hour trek, took 16 hours.

“If I'd known what I know now, I wouldn’t have trailered it,” he says. “Trans perfect,”

The trip wasn’t a total nightmare, however. He did get the big Bonneville home safely. “I was asked twice on the way back if I wanted to sell it,” Jole says. It helped bolster his belief that he had made a good purchase.

Upon further inspection in the comfort of his own garage, Jole found the Bonneville to be in better shape than he had thought when he fell in love with it in a restaurant parking lot back in Asheville. It was a well-equipped, top-of-the-line Pontiac convertible in very good original condition.

Jole purchased the car from the original owner's estate, and he thinks the fact that the owner hadn’t driven the car for about 10 years due to illness probably contributed to its well preserved state.

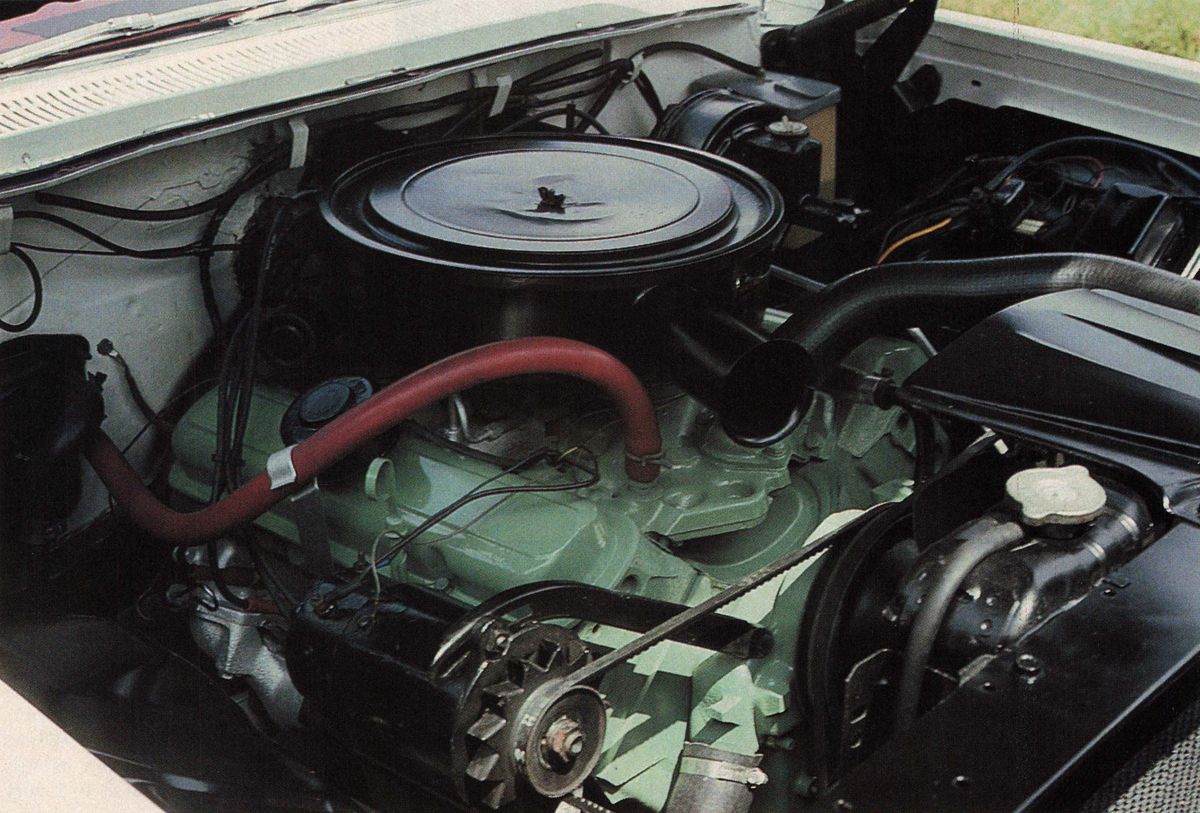

With 126,000 miles showing on the odometer, the car runs and drives beautifully, and the 389-cubic-inch, 303-horsepower, four-barrel V-8 doesn’t use any oil to speak of, Jole says.

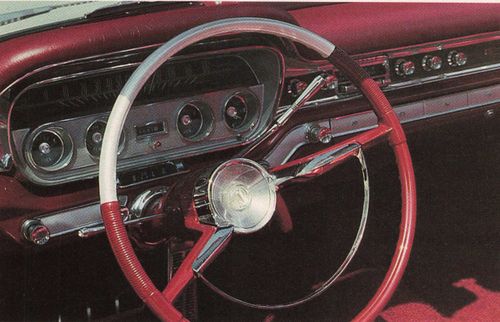

Even the clock works, along with all the other gauges, he says.

Subsequent research confirmed the Bonneville as a factory bucketseat car with the optional leather tritone upholstery, air and power windows. Unfortunately, the leather was a bit too worn for rejuvenation, Jole says, so he had a local upholstery shop duplicate the pattern and colors in vinyl.

Hes also. had the bumpers rechromed, though they were in pretty good original shape.

“They were good, but weren’t show quality,” Jole says.

He took the trim off, delivered the car to a local body shop for prep and repainting and was pleasantly surprised to discover neither rust nor body-filler on the body. Jole also had the cracked steering wheel filled and repainted and commissioned a local muffler shop to fabricate a new exhaust system.

Because the engine was in such good shape, Jole didn’t want to tamper with it, but this meant he had to paint and detail the engine in place, a tedious and labor-intensive job.

“I probably spent two, three days On it, getting in there with a toothbrush and some mineral spirits,” he says. The correct engine color for 1960 Pontiacs is a light, almost sky-blue.”

Like many owners of late ’50s and early ’60s cars, Jole had been waiting a long time to buy the car of his dreams.

“I was a senior in high school when that car came out,” Jole says. “I always kept my eye out for one.

When I spied that one, I knew I wanted it.”

Jole opted to buy the best car he could find rather than bring a ne- | glected car back to life. But regardless of the route 1960 Pontiac lovers take to ownership, a lot of resources are available if they make the effort to tap into an enthusiastic national network.

The Experts and the Engines Among those resources are the Sixty Owners Society, based in Nashville, Tennessee; the Pontiac-Oakland Club International, in Bradenton, Florida, and the Oakland/Pontiac Enthusiasts Organization in Waterford, Michigan.

Doug Bendle, known to some as the “1960 Pontiac Guru” and founder of the Sixty Owners Society, is steward of a wealth of information he’s eager to share with other owners. He owns two 1960 Ventura coupes himself.

One example of Bendle’s handsom involvement: He remembers Jole’s Bonneville from the society’s registry and confirms from its VIN and various codes that it is a very early, very well-equipped car that came from the factory with leather bucket seats.

The Bonneville’s VIN, 860D1108, shows in the D and the last three digits that it was the 108th Bonneville produced at the Doraville, Georgia, plant. The early production number is consistent with the engine number — 006812 — Bendle says, and the B1 engine code designates a 389-cubic-inch, 303 horsepower, four-barrel V-8 with 10.25:1 compression ratio.

All Pontiac engines for 1960 had the same bore and stroke and the same 389-cubic-inch displacement. But three different compression ratios, three different carburetor setups and three different camshafts allowed a total of seven different horsepower ratings, all the way up to a 348-horsepower, triple-carb, 10.75:1 compression version, according to the May 1960 Hot Rod Magazine.

These high-compression ratios can present something of a problem for driving on today’s no-lead, 93-octane maximum gasolines. (For a discus sion of high-compression engines, octane boosters and lead additives, see the March 1996 issue of CAR.)

However, yesterday’s answer to an economy problem may help provide today’s solution to the compression problem. Pontiac offered an E (economy) version of the 389 as the standard engine on many 1960 models for Pontiac buyers more concerned with reasonable power and economy than all-out performance. The E motors came with dished pistons providing an easy-going 8.60:1 compression ratio. The E motors also came with smaller, two-barrel carburetors, a long-legged 2.69:1 final drive ratio and milder cams, Bendle says.

The E motors were standard in many manual-shift models and a no cost option for Hydra-Matics.

For those who can find a 1960 Pontiac with one of these engines, 93 octane (or less) fuel should be more than adequate for the compression ratio, though hardened valve seats still would be a good idea for

drivers who are going to drive their cars hard or long. The engine codes — for example, E3 designating an economy 389 with Hydra-Matic transmission — are stamped into the right front of the block, Bendle says.

Performance should be respectable even with the least powerful economy motor; 215 horsepower and 390 lb.-ft. of torque.

Another option is to replace high compression pistons with the dished, low-compression pistons. Kanter Auto Products offers a complete set of dished, low-compression pistons in various oversize bores for $320. They also offer virtually all engine parts for the 389, including a complete rebuild kit for $540.

Crankshafts, however, may be hard to find and might have to come from a used parts source, Bendle says.

Another Pontiac parts specialist, Ames Performance’ Engineering, doesn’t offer internal engine parts. However, Bendle says Ames is one of best sources of general restoration parts for the big Pontiacs.

Another member of the nationwide Pontiac network, Rick Gonser, a technical adviser for the PontiacOakland Club International, agrees that the high compression ratios are one of the major headaches associated with the 389 engines.

However, if originality is not an issue, upgrades with later Pontiac engines are possible. Even Pontiac’s big 455-cubic-inch V-8 of the ’70s can be made to bolt right in, Gonser says, though these are “getting scarcer by the minute.”

The 1970 versions of this engine, with compression ratios of 10.0:1 and 10.25:1, won’t be much help with the low-octane gas problem. But beginning in 1971, compression ratios dropped precipitously, to 8.2:1. In 1973 and ’74, all of the 455s but the Super Duty (engine code X) version had compression ratios of 8.0:1, according to a Chilton’s Auto Repair Manual from the period.

Obviously, an antique car with a non-original engine is likely to be considered less valuable and less show-worthy than a similar car with an original drivetrain.

The Transmissions

The four-speed Hydra-Matic transmission offered in the 1960 Pontiac was an excellent transmission, Bendle says. However, Gonser points out it can be difficult to find someone who really knows how to work on them and that some parts, such as seals, are difficult to locate.

The rare four-speed manual transmission is a different story. Though considered very desirable by collectors today, the union of the Borg Warner T-10 Corvette four-speed and the massive Pontiac apparently was not a happy marriage. Gonser says these transmissions were too easy to break, and in his opinion the gearbox is too weak for the combination of high torque and heavy weight of the Pontiacs.

Bendle agrees

“To find one intact is very unusual,” he says. “It was a misapplication in my opinion.”

In fairness to the T-10 gearbox, which worked just fine in the lighter, small-block Corvette, it probably didn’t help that many of the four speed-equipped 1960 Pontiacs went to the drag strip. Pontiac was a hot car in drag racing and in NASCAR in 1960. Among its many victories, Pontiac was the 1960 Daytona Top Stock Eliminator.

Anyone lucky enough to find one of the survivors from the 722 1960 Pontiacs equipped with the factory four-speed should go easy on the clutch and the throttle, Bendle says.

“If you’re going to drive the car and occasionally get on it, it should be adequate,” he says.

Pontiac also offered standard and heavy-duty three-speed, column-shift manual gearboxes in 1960, according to Hot Rod Magazine.

The Running Gear

The differentials offered in 1960 Pontiacs are very good, Gonser says, “stronger than a Ford nine-inch.” If you do need a replacement, the problem may be finding one that hasn’t been “scooped up by the racers,” he says.

Pontiac offered three different differential cases in 1960 with several different gear sets, Gonser says. Parts for the Safe-T-Track limited-slip differential may be difficult to find.

The brakes are pretty straightforward to work on, Bendle says, usually needing — as most cars will — wheel cylinders if the car has been sitting and possibly lines and clips. Sleeving the master cylinder is a good option if the original is corroded or pitted.

In Gonser’s opinion, the standard brakes are a bit under-engineered, especially for the heaviest Bonnevilles. But Pontiac provided an in house upgrade in the form of optional Kelsey-Hayes eight-lug finned aluminum wheels with integral, steel-lined brake drums. However, these come very dear if you can find them, as much as $1400 for a set of four, Gonser says.

The front wheel bearings can be troublesome, Gonser says, probably because they weren’t up to the added stress of Pontiac’s “wide track,” introduced with the 1959 model. 1960 was the last model year Pontiac used ball bearings.

One possible fix is to use wheels and bearings that came on later models. For the 1961 model year, Pontiac switched to stronger tapered roller bearings.

The replacement A2 and AO tapered bearings are still available and will fit the 1960 spindle, says Bendle, and he recommends the switch.

The front springs sometimes get tired and allow the front ends to drop, especially if the car has seen drag strip service, Bendle says, but springs and suspension rebuild kits are readily available from Kanter and other suppliers.

Another potential weakness is the result of an engineering accommodation made to the 1960 Pontiac’s cruciform frame — a two-piece drive shaft. The center bearing support, where the drive shaft penetrates the center of the X, is just not up to the job, Gonser says.

“Pop the clutch one time, and it’s gone,” he says.

The two-piece drive shaft requires three universal joints, and the center U-joint came without a grease fitting. But a Zerk fitting is easy enough to install and a good idea, Bendle says.

The Bodies and Frames

Like most cars that have been around more than 35 years, 1960 Pontiacs are likely to have some rust problems.

Gonser advocates a careful check of the frame rails, especially over the rear wheel arch. Floor pans, especially on convertibles and hardtops, frequently have rusted.

And the trunk floors commonly rust where moisture collects and remains under the rubber mat.

The top front edge of the front fenders, the trailing edge of the front fenders, over the rear wheel wells, and the rocker panels near the front edge all are rust-prone, Bendle says.

Here again, trapped moisture generally is to blame for the rust problems in these areas as well.

Bonnevilles with rusty floors may present a special problem. It is possible to buy reproduction floor pans for 1960 Catalinas, Gonser says, but these won't fit the 124-in. wheelbase Bonnevilles, so a skilled metal worker will have to fabricate patch panels.

Other panels may also be hard to locate. Even when it’s possible to find a donor car for sheetmetal parts, this isn’t necessarily a very good solution, Gonser says.

“My welder will say, ‘’m not welding that old rusty piece of crap to another old rusty piece of crap,” Gonser says. “All this welding requires a super body person; none of that’s cheap.”

All things considered, the big Pontiacs of this era can be expensive cars to restore, Gonser says.

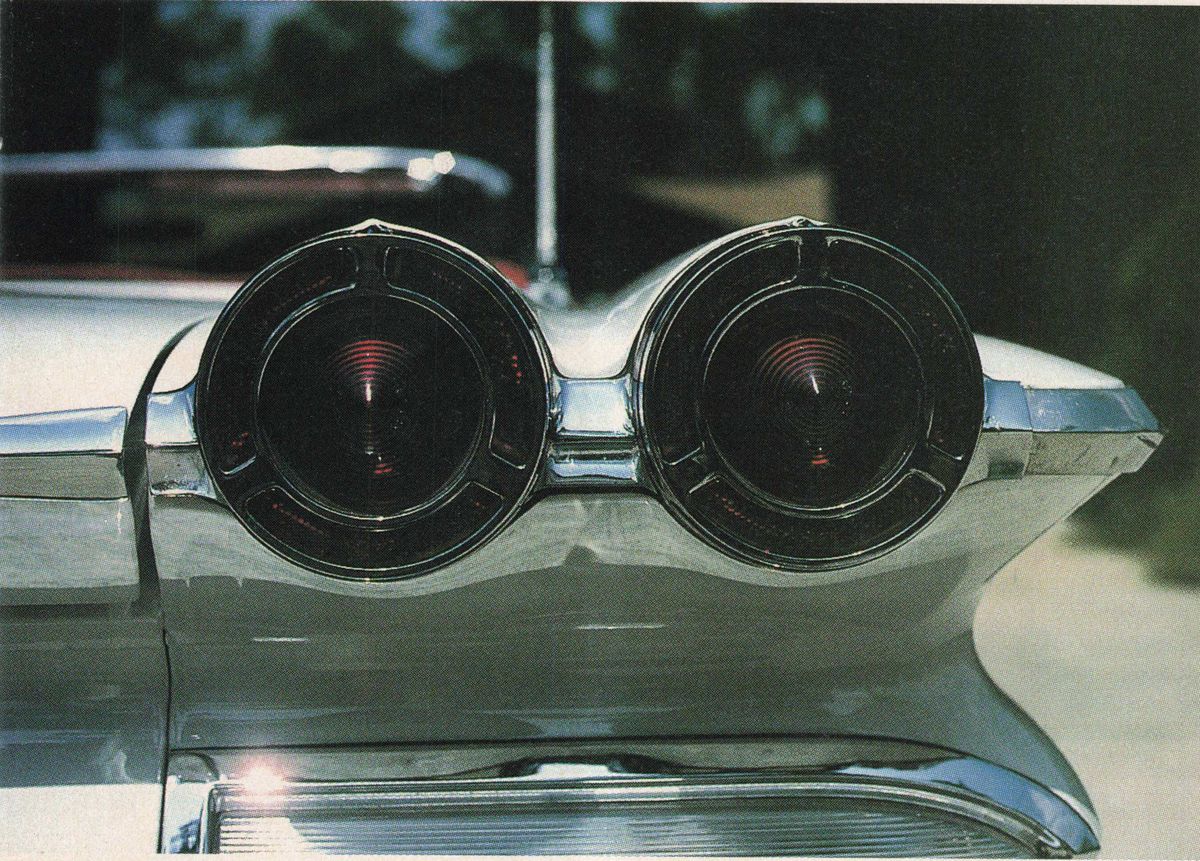

“If you’re going to restore a big car, first plan carefully,” he says. “I show them (would-be restorers) the $35,000 to $40,000 worth of receipts.” WITH ITS GLEAMING exterior and extensive use of brightwork inside, this Pontiac Is just the ticket for a long cruise on a sunny day. Today’s convertibles might be fun, but its hard to imagine that they could match this car’s wide-track ride.

Price guides show Bonneville convertibles (17,062 produced) worth from about $1000 for a parts car up to about $30,000 for a No. 1 show car.

But the people who like these cars see them as well worth some extra effort. Pontiac was General Motors’ performance division in this era, and the big “wide-track” Pontiacs have lingered in many minds as something special.

Bendle, for one, is not shy about touting the merits of his favorite car.

“The 1960 car did just about everything well — looked good, ran great and provided reliable transportation — a real balanced car in a very competitive, auto-oriented era,” he says.