1958 Chevy Impala

Better Than Expected

Some projects — like this 1958 Impala — take you on a joy ride before you ever turn the Rey.

BY HOYT CHILDERS

t first blush some car deals Aw like they were made in

heaven, but later on you find that the guy who sold you that car must have had the heart of the devil beating inside. Gary Wright’s deal on a 1958 Chevrolet sort of worked the other way around.

On the Fourth of July weekend in 1993, Wright was lured to Houston, Texas, from his home in the Florida Panhandle. When he arrived, disappointment greeted him. The 1958 Chevrolet Impala Sport Coupe that had sounded so good in the Old Car Trader didn’t look all that good up close, at least on first inspection at the consignment dealership.

His first thought was, “Boy, we’ve made a 700-and-something-mile trip for nothing. It was an ugly car.” The Impala was supposed to be a mostly restored matching numbers car that had received a frame-off body restoration, total engine and transmission rebuild and a lot of other work.

It had been painted in the original Cay Coral — an odd, somewhat pinkish light chocolate, but the paint needed additional buffing. “That particular color not being buffed out was not a very pretty color,” Wright says.

Also, the car didn’t sound good when it ran because of a leaky exhaust system, Wright says, and a vibration made Wright wonder if the crankshaft was bad in the 348-cubic inch V-8. “They were known for — at high rpms — not getting enough oil to the mains and coming unglued,” Wright says.

But Wright had taken along a knowledgeable friend who, on closer inspection of the Impala, surprised him by saying, “I believe it’s more car than you think it is.” In the end, Wright decided he could “see the basis of a good car,” struck a deal for $11,500 and trailered it back home.

Even though Wright drove through torrential downpours on the trip, there was no water inside the car when he got home — a good sign in a 35-year-old hardtop.

Despite this feat, his wife was not impressed. She agreed it was real ugly, he remembers with a laugh. But his 16-year-old daughter seemed proud of it, and for a while Wright's plan was to finish restoring the Impala and then sell it for profit to buy his daughter’s first car.

But that was before he began to dig into the car’s history. “I didn’t realize how much car IJ had,” Wright says. As it turned out, he needn’t have worried. When he got back home, he was able to contact the previous owner, Sam Grice, an old car enthusiast and the man responsible for the restoration of his car. Grice detailed all the work completed in his shop and also said he believed the vibration Wright was worried about was a problem with the flywheel. In the end, Wright says, everything Grice said about the condition of the car proved to be true. But that’s getting ahead of the story. As work on the car progressed, it began to dawn on Wright that F58K159545 really was a rare, mechanically original, 58 Impala. He researched the car’s various tags and numbers, using the Late Great Chevys Information Data and Judging Guidelines Manual, and found that everything did indeed match the car’s factory-original configuration.

Even the headlights were the original type that now cost $100 or more apiece, Wright says.

The family grew attached to the car. That odd Cay Coral paint looked remarkably good after it had been rubbed out and shined. The plan for the Impala’s future changed; Wright sold a 1957 Bel Air he already owned — and had planned to keep forever — and kept the Impala instead.

The good news continued. An out-of-balance flywheel was indeed the cause of the driveline vibration. The flywheel was warped, Wright says, and he got a replacement at Late Great Chevys (the national club for 1958-64 Chevrolets) for $110.

The 348-cubic-inch engine and the Powerglide transmission both were fine, but the engine was “an ugly looking mess” cosmetically, so Wright removed the radiator to facilitate engine painting, detailing and replacement of all hoses, clamps and belts. He bought a replica “tar top” battery through Late Great Chevys for $139.

Wright thinks the easy-going, two-speed Powerglide transmission probably contributed to the preservation of his Impala’s engine.

Wright had the differential “pumpkin” rebuilt, but retained the case with the proper numbers for the sake of originality.

When Wright bought the car, Grice already had re-covered the seats in the proper, multi-tone Cay Coral cloth and vinyl. But the carpet was the wrong color (see sidebar), some of the gauges and controls were not working, and the steering wheel needed restoration. Wright stripped the interior — down to the bare metal floor — and dismantled the dash and instrument panel.

Again, Wright was pleasantly surprised; the floor was very good. There was a bit of surface rust, but no holes. Wright cleaned and painted the floor and installed new padding and reproduction Cay Coral carpeting. Wright decided that it would be prudent to rebuild or replace everything under the dash that needed attention while he had the instrument panel and steering wheel out. Items he replaced or repaired included the speedometer, heater and vent controls and cables, the wiper assembly, heater core, clock, radio and speakers.

Late Great Chevys restored the steering wheel for about $175, he says.

Finding parts sources generally was not a problem, Wright says. Many mechanical parts were available locally, and most everything else came from Late Great Chevys, a club for 1958 through ’64 Chevys that works with a variety of suppliers, offers discounts to members and monitors product complaints.

Wright installed a new liner in the trunk and found an original-equipment jack at a car show in Moultrie, Georgia, to finish off the luggage compartment.

Wright also made one cosmetic change from the car’s showroom condition; he thought a white top would help make the Impala a real eye-catcher. Discussions with Chevy experts convinced him that dealers in the 1950s frequently two-toned cars that had come from the factory with a single paint code, so he had the top repainted in Arctic White, an authentic Chevrolet color for 1958.

This minor color change is indicative of Wright’s attitude toward his Impala. While he isn’t fanatical about it, he has taken pains to keep the car as authentic as possible. He recently had to replace the voltage regulator, but kept the original just so he’d have the part that actually came in the car.

“Other than the starter and voltage regulator, so far as I know everything is original,” Wright says.

But this isn’t a pampered show car that never turns a wheel on a public highway. He owns the car to enjoy it, and he drives it.

And he enjoys owning a Chevy that’s a bit unusual. Car shows abound with the popular ’55, 56 and ’57 Chevys; but sometimes Wright’s Impala will be the only ’58 in attendance. It's a common story — car enthusiasts who are now in their 30s, 40s or 50s fell in love with their dream cars back in high school and waited decades to actually own one.

Gary Wright, owner of the subject car, remembers the night he fell in love like it was yesterday.

When he was a kid in a small town in Georgia one Sunday night about 8:30, a night watchman and he were listening to the stop light turn off when in the distance they heard the powerful growl of a big V-8 running at high speed. A few moments later, a white 1958 Impala Sport Coupe flashed through town with a Georgia Highway Patrol cruiser in hot pursuit.

Wright hastens to say that he doesn’t condone unlawful, dangerous and reckless driving. Nevertheless, the image of the powerful 58 Chevy stuck with him.

“| had to know what that thing was,” he says. “That's the first one | remember ever seeing.”

It was 35 years before Wright fulfilled his dream of owning a ‘58 Impala. He drives and enjoys his Impala, but he also considers auto restoration a kind of cultural and historical preservation.

“That 58 Impala represents somebody’s dreams and ambitions, kind of like art,” he says. “If you can preserve and restore it, it’s the ethical thing to do.” am Grice, a Sugar

Land, Texas, paint, body and restoration specialist, owned the subject | car before Gary Wright and had partially restored the Impala prior to the sale.

He remembers the project well, especially the unusual Cay Coral paint scheme and the problems it caused on the interior.

“I had a real rough time getting the material for that car,’ Grice says.

In fact, Grice says he actually had given up on finding the Cay Coral interior material and decided to change the whole color scheme of the car to a more common factory combination — black exterior with a red interior.

But good luck intervened; a friend found a vendor who had several yards of new old stock Cay Coral fabric needed for the seats.

“That was NOS we just stumbled onto,” Grice says. He remains convinced the last piece of NOS Cay Coral fabric ~ available in the country now covers the seats of Wright's Impala. He wasn’t so fortunate in the floor-covering department, however, and when Grice sold the car, it still had red carpet on its floors. (The new owner, Gary Wright, installed reproduction Cay Coral carpeting.)

The 58 Impala is not an easy — or inexpensive — car to restore, Grice says.

__ “If a person is looking to make a ton of money, | don’t recommend the ’58 Chevy,” he says. Grice spent about $15,000 on the Impala, and took a $3500 loss when he sold the car. A couple of the tricky jobs on ’58s are installing headliners and re-chroming the bumpers, Grice says.

The bumpers are in three pieces, bolted together through flanges, he says. The presses the chrome shop used for straightening his bumpers bent the bolting flanges, and the pieces wouldn't align properly on reassembly. It took some hard work on Grice’s part to bend and align the flanges to their original configuration.

The combination of the curvy rear of the Impala roof and non-stretchy vinyl material makes the headliner a challenge, Grice says. It is almost impossible to install the headliner without unwanted creases, and the job took him the better part of a whole day.

During the mechanical restoration, Grice remembers one real problem with the 348-cubic-inch V-8 engine: “We couldn't find valve guides for it.” Grice’s ultimate solution illustrates the innovation often required in auto restoration. The valve stems in Wright's 348-cubic-inch V8 now slide through guides from a 6.2-liter GM diesel. He had to rebore the inside diameter to fit the original valve stems, but otherwise the diesel valve guides fit perfectly, Grice says. Grice likes the 348 cubic-inch engines and remembers them being tough and powerful. He says he doesn’t remember hearing of the high-rpm oil-supply problem Wright mentions. He says he owned Chevrolets with the

348-cubic-inch engine — and drove them hard — when he was a young man and never heard of them coming apart.

“If it wouldn’t get rubber in three gears, we didn’t want it,” he says with a chuckle.

Besides the 348-cubic inch V-8, Chevrolet also offered the smaller 283 cubic-inch V-8 and a 235.5-cubic-inch six-cylinder in its 1958 models. Factory engine packages most sought-after by collectors are the 348-cubic- © inch motor with three two-barrel carburetors or the rare, fuel-injected version of the 283-cubic-inch engine. A four-part stamping near the front of the block on the passenger side will help you to determine how your engine started life. The first entry on the stamping will tell you the engine’s source, the second and third the month and day of its production, and the last is the engine type. For example, the stamping F 01 23 D, tells you the engine was built in Flint, Michigan, on January 23 and it was built as a 283-cubic inch V-8 teamed with a Powerglide transmission. Unfortunately, there’s no way to tell exactly what type of engine and fuel-delivery system came with the car unless you can locate a build sheet. The only thing the - cowl and VIN plates will ~ tell you is whether the car

was built with a six or V-8 According to a January 1958 Car Life article, either the 283 or 348 were available on any 1958 Chevrolet. The 283-cubicinch engine has an excel_ lent reputation; for a daily :

driver, the standard 283_cubic-inch, 8.5:1 compression engine with a two - barrel carburetor would be ~

a good choice.

let Powerglide automatic is

sion to work on, Grice

says, andis avery sturdy _

design in a heavy cast-iron case. It’s able to handle far more horsepower and

_ torque than any stock ‘58 Chevy produces, he says, adding that drag racers

have used the Powerglide _

with engines producing 1000 horsepower.

If itis necessary to drop —

_ the transmission, be sure

_to mark the position of the —

flywheel relative to the

torque converter. It’s prop erly balanced in one posi tion and should be bolted

_ back the way it came out,

Grice says.

Chevrolet also offered a three-speed manual

transmission, three-speed —

with overdrive and the _ torque converter Turboglide three-speed auto ~ matic on the 1958 Chevys.

An unusual option offered on the 1958 Chevy

_ was air suspension, a con troversial GM setup where air bladders replaced the car's springs. This system was troublesome when new and likely would be far more so now. Standard - suspension is coil springs at all four corners. Body-wise, the subject car was very sound when he bought it, Grice says. One of the most rust-prone areas on the 58 Chevrolet _ is the bottom of the front fender just forward of the door, but this car didn’t

have rust there, he says.

The trunk floor panel

_ showed some surface rust that gave way to pinholes

when Grice cleaned it up with a wire wheel. He’s de veloped a repair technique | for retaining the factory ap- —

paint and grinds away all the visible rust. Then he

_ treats the metal with a rust

converter, a product that

_ chemically changes rust

into an inert material. When the rust converter has

cured properly and turned

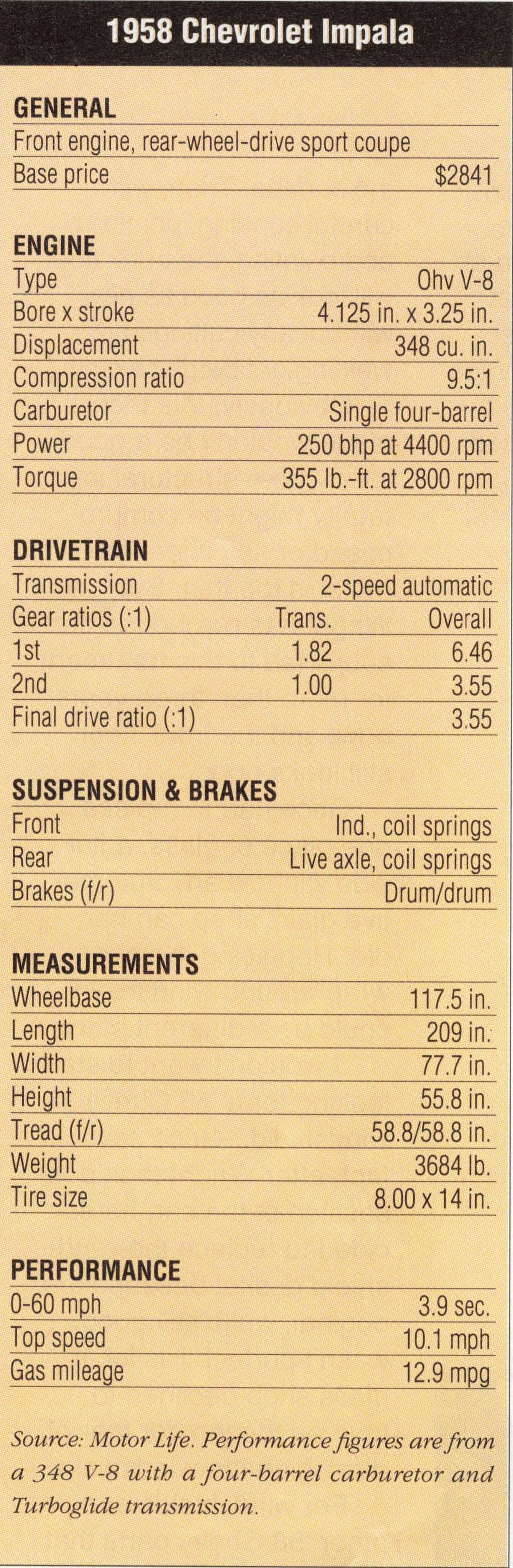

THE 348-CUBIC-INCH engine with four-barrel carburetor.

- pearance of the original

sheetmetal, provided it’s not too weak or thin. First, Grice removes the

the metal black, he paints

the surface with a coating of fiberglass resin to seal the pinholes and smooth

the surface. Then, with careful sanding, priming and painting, the trunk floor will look as good as new without any cutting and welding or fiberglass cloth.

Obviously, this tech-nique wouldn't be a good idea where structural integrity might be compromised or anywhere the metal is too thin. But Wright has owned the car subjected to this treatment for more than three years now, and the trunk floor still looks good.

Grice had to replace © one piece of glass, a flat side window any automotive glass shop can handie. Replacing the big wrap-around windshield could be a different story.

“| wouldn’t want to start looking for a 58 Chevy windshield,” Grice says. In fact, after Wright took possession of the car, he de cided to replace the wind shield gasket because the

original, while still good, —

wasn’t perfect. His local glass shop declined to take on the job, for fear of damaging the windshield.

For windshields and other ’58 Chevy parts that are difficult or impossible to find new, used parts dealers may be the only option. Auto City Classic, a Minnesota used-parts dealer specializing in 58 Chevrolets, offers windshields for $339.

Current price guides show 1958 Impala hardtops worth $1000 for a parts car all the way up to $28,000 for a No. 1 car. Convertibles, as usual, have higher values, ranging up to $49,000 in the price listings.