1949 Cadillac Coupe

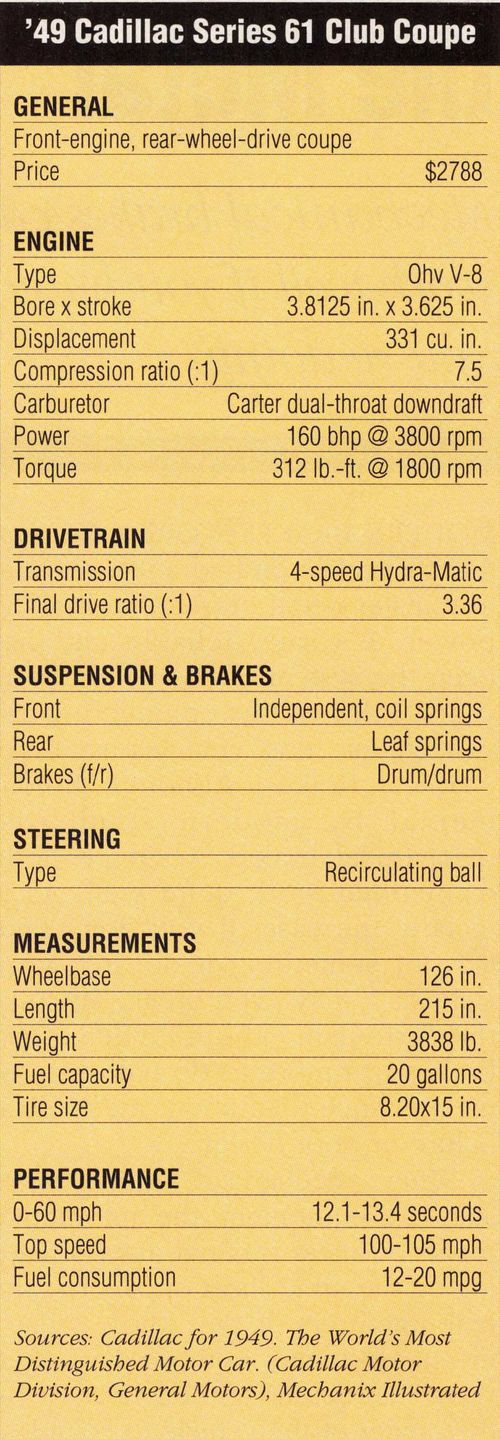

Distinctive fastback-type styling and the first of the modern overhead valve V-8 engines are two good reasons for checking out the 1949 Cadillac two-door coupe. Here’s an automobile that delivered the message: “If you want to get on the fast track to success, then you better be driving one of these.” Status was assured by virtue of the well-established Cadillac standard. The two-door coupe body style, often referred to as the sedanet, was streamlined and somewhat influenced by European auto design. Most of all it was distinctive and futuristic. Some people also call this style a club coupe although Cadillac literature does not refer to this term. It was first featured on the 1941 Cadillac and was eventually used throughout the General Motors line.

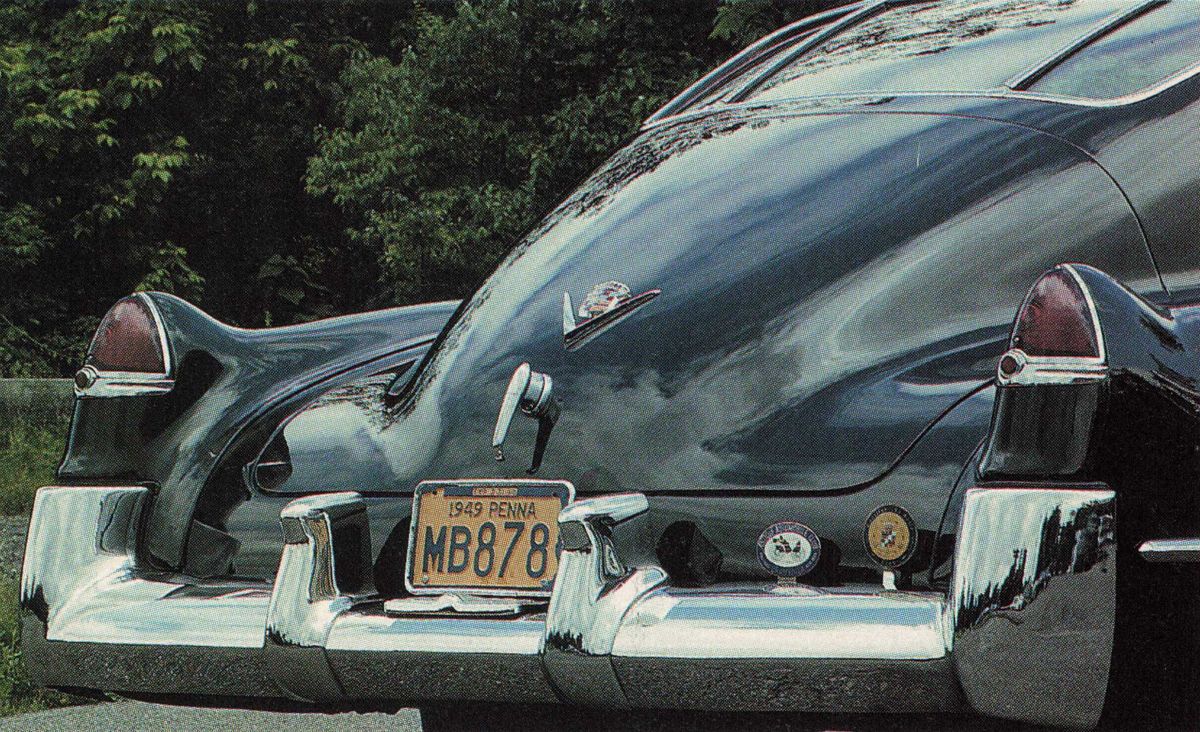

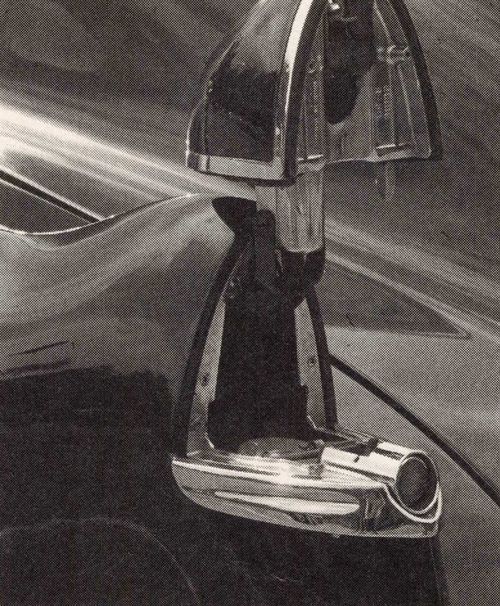

The fastback lines returned after World War II, and in 1948 an additional element was added — tailfins. These fins, which grew in size and eventually became symbolic of flamboyant ’50s cars, were adapted from a highly successful fighter plane, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Given the country’s postwar fascination with aircraft, it’s hardly surprising that a major automotive design cue would come from a famous airplane with prominent twin rudders. Even Time magazine took note of the styling departure, observing that “by introducing rear fenders with raised fins, Cadillac raised customers’ brows.” But while the fins caught on in a big way, the fastback/fins combination didn’t go over with the buying public. In 1948 some 8300 club coupes were sold, followed by sales of nearly 14,000 in ’49, the final year for that style.

Although it is not what you would call a common car, restoring a ’49 Cadillac club coupe is not as difficult as you might imagine. In fact, tracking down a car, and if necessary, the parts with which to restore it, can be relatively easy compared to a lot of automobiles.

The former owner of this car, Bill Edmunds of Devon, Pennsylvania, says anyone who is willing to do some digging will be able to find a variety of parts sources. “The engine continued pretty much unchanged, albeit bored out and stroked, for the next decade,” Edmunds notes. “So engine parts and other mechanical parts are not difficult to get.” The engine was used throughout the Cadillac lineup in 1949 and the same basic engine was used in Cadillacs up through the early 1960s.

Edmunds also owns a 1960 Cadillac. Comparing the two cars, he says the 1949 has “a lot more power” and could “pull away from” the 1960 Caddy. To explain this, he concludes that the ’49 was not as heavy, was geared better and the engine was freshly rebuilt. As a comparison, the engine in the ’49 measured 331 cubic inches and was rated at 160 horsepower. The 1960 Cadillac engine was 390 cubic inches and rated at 315 horsepower.

Virtually all Cadillacs in 1949 were equipped with Hydra-Matic transmissions, General Motors’ four-speed automatic. The time-tested opinion on these transmissions is that they were durable, extremely reliable, but rather harsh in their shifting tendencies. In their day they were extremely popular. Oldsmobile first offered the Hydra-Matic in 1940 and it remained essentially unchanged until 1956 when it evolved into the Jet-AWay Hydra-Matic. During World War II the Hydra-Matic was used in Sherman tanks, and in addition to -

The ’48 and ’49 Cadillacs are popular cars to restore, although there is some difference of opinion regarding which model is the most interesting and significant. Some prefer the 1948 L-head version for its historic standing as the last flathead Cadillac, while the 1949 club coupe is the only Cadillac fastback to come with the overhead V-8. Edmunds said reproduction parts, such as lenses, rubber parts and upholstery, are readily available for the cars.

For ’49s like our feature restoration, much of the sheetmetal is interchangeable with other Cadillac models from that year and to a lesser degree with models from 1948. According to Jay Friedman, one of the Cadillac-LaSalle Club technicians for the 1949 Cadillac, from the cowl forward all 1949 Cadillacs shared the same sheetmetal. Front and rear bumpers are interchangeable.

Many interior fittings and the taillights are also shared. The taillights are also shared with the 1948 models, but because of the engine modernization the hood is slightly different and the grille was updated. The similarities make it easy to purchase the wrong part unless you carry photos or a reference that will point out some of the minor differences. Since there are plenty of 1949s to be found, it is usually unnecessary to borrow from 1948 parts cars. At least not yet.

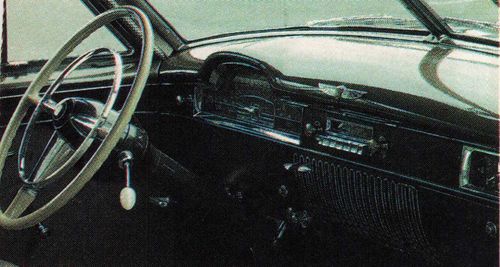

There is also the distinction between Series 61 and Series 62 cars in the two-door coupe as well as the four-door sedan models. As a rule the Series 62 cars featured chrome guards on the rocker panels and a gravel guard behind the front wheels. They also offered an upgraded interior with Bedford cord upholstery and chrome moldings around the windshield and windows. Very few of the sedanets were equipped with the hydro-electric power windows and seats. This turns out to be a blessing since these units are often a source of trouble. The full-power system was standard equipment on the convertibles and the Coupe DeVille — the first of Cadillac’s hardtops.

Sheetmetal parts can be found at swap meets and parts cars are reasonably available Edmunds says, “but it’s not as easy as finding parts for a 57 Chevy. You can get rough rocker panels if you need them, but you'll have some welding and filling to do.”

When you are working on a car like this you learn to “buy the stuff when you see it” whether you need it at that time or not. “I was at Hershey a couple of years ago and a chap had a rear window for a ’48-49 sedanet. I bought it. I didn’t need one, but a spare rear window would’ve been handy if I’d needed it or needed to trade it for something else.”

If you are pricing Cadillacs of this vintage, Edmunds says you will find the club coupe at about one-third to one-half the cost of the convertible model. Convertibles of this era didn’t survive as well, therefore they are more rare and more highly prized by collectors. The Coupe DeVille of this year was a mid-year introduction and produced in small numbers so it too is both rare and relatively expensive.

Various price guides value a ’48 or ’49 club coupe in either the Series 61 or 62 at less than $1000 for a parts car to more than $20,000 for an example in top condition.

Edmunds and Friedman advise prospective buyers to check for rust in some of the logical places. Behind the fender skirts and gravel shields are a good place to start. The front fender wheel opening also had a tendency to collect water and mud. Another component to pay attention to is the rear bumper. Many are rust ed at the ends from years of dirt and water being kicked up by the wheels. Good replacements are one of the more difficult items to find.

He warned that a prospective owner should look carefully at a car’s chrome before buying it.

“Know what you're going to invest in chrome plating,” he said. “That’s the key thing. You can get the stuff, but the price of good plating is high. There’s an awful lot of mediocre stuff out there with waves in it, grind marks in it.

“But it’s important to get it done right, especially with the Series 61 because it’s such a plain car, the chrome stands out. When it’s done improperly, it ruins the appearance of the car.”

The chrome side” ‘spears are unique to the club coupe. Edmunds purchased a pair of replacements at the Hershey Swap Meet. He paid $100 for the pair, then paid $400 to have them replated. The front portion of the chrome spear had a tendency to trap water and sometimes can look good on the outside, but be rust-damaged on the inside.

Other items that are unique to the club coupe and difficult to locate in good shape are the trunk handle and the Cadillac emblem that adorns the trunk.

Edmunds says his car was in good condition when he purchased it in Virginia in late 1988. Much of the restoration had been completed prior to his purchase. Since he acquired it, the brakes, exhaust, and interior were redone, all of the chrome trim was replated, and the car was detailed. It won its AACA First Junior at Hershey in 1993, and its First Senior award at Montoursville, Pennsylvania, the following spring.

The reactions from people much too young to remember the car when it was new continually surprised Edmunds. “I spent a lot of time showing the gas tank filler access under the taillight. That, and the fastback styling. You don’t see that often. I think it attracts a lot of attention, especially going down the highway. It looks great from the rear end. The front end is relatively unremarkable.” There’s no denying this car stands out in a crowd.

On the highway, it’s very controllable, despite the fact that it is “a big, heavy front end on a car without power steering and without power brakes. I understand why power steering became a very popular option very early on.”

Friedman has his own sedanet and has driven it on tours of more than 1000 miles on three separate occasions. He says the car is “very comfortable at freeway speeds” and that the brakes are “powerful” because the linings cover a large surface area (a big improvement over 1948). He also notes that the steering ratio is low so you get a lot of turns lock-to-lock, “but the wheel is huge so you have a lot of leverage.”

“It’s a terribly hot car in the summer,” Edmunds says. “The air ducts that move air from the front of the car run right past the engine, so that heats the air anyway and there goes their whole use.” He, nonetheless, enjoyed the opportunity to drive the car (his longest trip was 200 miles) once he accomplished the type of restoration that’s recognized by the AACA. Edmunds misses the “treasure hunt” aspect of the restoration. For him that’s a big part of the enjoyment. Maybe that’s why he recently sold his sedanet and is currently in the process of restoring a 1949 Coupe DeVille. “It was a challenge to get the Senior (AACA award),” he said. “That’s been enjoyable, but some of that’s gone now that it’s been achieved.”

Enter the modern era of engine design.

It's a line from "The Penalty of Leadership," a 1915 Cadillac advertisement which has become a classic of automotive marketing. Thirty-four years after it was published, Cadillac introduced its overhead-valve V-8 as evidence that it continued to be a leader.

In 1948, Cadillac had introduced its first new postwar styling. The advertising claims unabashedly called it, "the most beautiful ever built." The ad went on to say that "beauty is only half the story of the great new Cadillacs for the exterior smartness is matched completely by the new mechanical goodness."

To be blunt, there was little about the "mechanical goodness" that was new. Unlike its styling, the 1948's engine was a continuation of the tried and true L-head (flathead) V-8. Cadillac's history of V-8s dated to 1914. Solid and reliable, the engine's 346 cubic-inch displacement was producing 150 horsepower, just as it had in 1947 and 1946 and 1941.

Built in 1949, "new mechanical goodness" became more than mere hype. A December 1948, ad called the new overhead valve V-8 a "creative masterpiece, " that "provides an amazing increase in power yet affords an increase in gasoline economy of approximately 20 percent. It is quick and eager beyond all experience; yet its power is so effortless that the driver is scarcely aware of the engine's existence." Serious claims, but Cadillac had been working to back them up for more than a decade.

The new V-8 had its beginnings in 1936, according to Cadillac, when engineers determined that the wave of the future would be less weight, more power, and high compression. That combination was a tall order, and the design team tried all sorts of possibilities through the remainder of the 1930s and into the early 1940s. Their work was cut short by the U.S. entry into World War I. Cadillac quietly stowed some experimental units for the duration, then dusted them off following VJ Day and resumed the project. By late 1945, the first blocks were being tested.

When it reached production, the ohv engine was a cast-iron 90-degree V-8 with hydraulic lifters. The five-main-bearing, 160-horsepower. ohv engine displaced 331 cubic inches. Compression was increased to 7.5:1 versus 7.25:1 for the old L-head. and it produced 312 lb.-ft of torque compared to 274 lb.-ft. from the older engine.

The real difference, though, was in the bore and stroke. On the L-head, the bore was 3.50 inches and the stroke 4.50, while the numbers on the ohv were 3.81 and 3.63 inches. "This combination." a Cadillac promotional booklet said, "contributes to greater efficiency by exposing about 12 percent less cylinder wall area to flame with a consequent reduction in heat loss and greater cooling efficiency, That meant less radiator capacity was required, and the cooling system was therefore reduced from 25 quarts to 18, a weight savings that complemented the 200-pound-lighter ohv.

"The shorter piston stroke reduces frictional power loss by cutting piston travel approximately 20 per cent," the booklet continued. "At 4000 rpm the piston travels only 2400 feet per minute as compared to 3000 feet per minute in previous models." That was a benefit not only in cutting the power lost to friction, but also in reducing wear. The ohv's pistons were slippers, designed to "nest" into the counterweights on the crankshaft so shorter connecting roads could be used. "Reduction of weight and inertia means faster acceleration." Cadillac reported, but reducing the mass of the pistons and connecting rods also meant smoother operation Additionally, the combination helped to make the oh several inches lower than the L-head, meaning the hood could be lower as well. (Take note if you thought of using a 1948 hood on a 1949 car.)

The basic oh engine remained in production into the 1960s without a major redesign. While its original 7.5:1 compression is modest by modern standards, it had been engineered to handle considerably higher ratios to take advantage of the highe-octane gasolines that were being developed.